|

The Economic Policy

That Made the Peace of Westphalia

by Pierre Beaudry

May, 2003 (EIR)

In view of the currently collapsing world financial system, which is tearing apart the Maastricht Treaty, European governments have a last opportunity to abandon the failed Anglo-Dutch liberal system of private central banking and globalization, and organize the new Eurasian axis of peace centered on Russia, Germany, and France. To solve the collapse as sovereign nation-states with a common interest, their historical foundation is the 17th-Century Peace of Westphalia, which began the "era of sovereign nation-states" and is now attacked by all the new imperialists and utopian military strategists.

The 1648 Westphalia Peace only succeeded because of an economic policy of protection and directed public credit—dirigism—aimed to create sovereign nation-states, and designed by France's Cardinal Jules Mazarin and his great protégé Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Colbert's dirigist policy of fair trade was the most effective weapon against the liberal free trade policy of central banking maritime powers of the British and Dutch oligarchies.

Similarly, it is only with a return to the Peace of Westphalia's principle of "forgiving the sins of the past," and of mutually beneficial economic development (see Treaty principles, the "benefit of the other''), that the current Israeli-Palestinian conflict could be solved on the basis of two mutually-recognized sovereign states.

In the Peace of Westphalia, Mazarin's and Colbert's common-good principle of the "Advantage of the other" triumphed over the imperial designs of both France's Louis XIV himself, and the Venetian-controlled Hapsburg Empire. In the 18th Century, the same principle brought the posthumous victory of Gottfrield Leibniz over John Locke in shaping the American republic's founding documents, the victory of "the pursuit of happiness" and the principle of the general welfare, over Locke's "life, liberty, and property."

Today, that principle has created the Eurasian Land-Bridge policy, as designed by U.S. Presidential pre-candidate Lyndon LaRouche, and as expressed in the economic development policies of China and some other Asian powers. This aims at "transport corridors of development," spanning Eurasia from the Straits of Gibraltar to the Bering Straits, and from the North Sea to the Korean Peninsula and Southeast Asia.

How Mazarin Looked Toward Westphalia

Principles of Westphalia

The Treaty of Westphalia of 1648, bringing an end to the Thirty Years' War, which had drowned Europe in blood in battles over religion, defined the principles of sovereignty and equality in numerous sub-contracts, and in this way became the constitution of the new system of states in Europe.

We quote the two key principles:

Article I begins:

"A Christian general and permanent peace, and true and honest friendship, must rule between the Holy Imperial Majesty and the Holy All-Christian Majesty, as well as between all and every ally and follower of the mentioned Imperial Majesty, the House of Austria ... and successors.... And this Peace must be so honest and seriously guarded and nourished that each part furthers the advantage, honor, and benefit of the other.... A faithful neighborliness should be renewed and flourish for peace and friendship, and flourish again."

Peace among sovereign nations requires, in other words, according to this principle, that each nation develops itself fully, and regards it as its self-interest to develop the others fully, and vice versa—a real "family of nations."

Article II says:

"On both sides, all should be forever forgotten and forgiven—what has from the beginning of the unrest, no matter how or where, from one side or the other, happened in terms of hostility—so that neither because of that, nor for any other reason or pretext, should anyone commit, or allow to happen, any hostility, unfriendliness, difficulty, or obstacle in respect to persons, their status, goods, or security itself, or through others, secretly or openly, directly or indirectly, under the pretense of the authority of the law, or by way of violence within the Kingdom, or anywhere outside of it, and any earlier contradictory treaties should not stand against this.

"Instead, [the fact that] each and every one, from one side and the other, both before and during the war, committed insults, violent acts, hostilities, damages, and injuries, without regard of persons or outcomes, should be completely put aside, so that everything, whatever one could demand from another under his name, will be forgotten to eternity."

Link to Complete Treaty of Westphalia

By the early 1640s, after witnessing so much abuse by the Hapsburg Emperor's feudal authority against the peoples of the small and war-devastated German states; and realizing that the horrors of the Thirty Years' War were leading toward the destruction of civilization, Cardinal Jules de Mazarin acted to shift the attention of Europe away from Venetian-manipulated religious conflicts, that had become an endless cycle of vengefulness of each against all. He sought to base a peace on the economic recovery and political sovereignty of the German Electorates and States, to move them towards freedom from the tyranny of the Emperor, and from Venice's intrigues.

In 1642, six years before the signing of the Peace of Westphalia was to end the Thirty Years' War, Mazarin sent a negotiating team to Munster to begin working on his peace plan. The two French plenipotentiaries, Claude de Mesmes Comte d'Avaux, and Abel Servien, were his close associates. The mission was to use the power of France to intervene between the Emperor and the German Electors and princes in such a way, that the Emperor would be forced to relinquish his overpowering authority, and France would facilitate an economic program for the German states by helping them rebuild their territories. However, this result could not be achieved unless France, as the most powerful nation outside of the Empire itself, were to be given the role of guarantor of German freedom on their own territory—a status of mediator that would give Mazarin's French plenipotentiaries a friendly and indirect right to intervene inside the government of the Empire. This had to be done in such a way as not to give umbrage to the German princes, who would have rejected any direct form of foreign intervention. Indeed, what would be the benefit of replacing an Austrian imperial power by a French one?

Mazarin organized his plenipotentiaries to make their presence necessary, primarily along the Rhine River, by engaging in the only form of French expansion that would correspond to Mazarin's principle of "the Advantage of the other," and that was, engage in a productive economy of fair trade and commerce. Thus, Mazarin began to play an entirely new and unique role inside the Empire by increasing German freedom in trade and commerce along the main waterways of the Empire.

The Rhine River, running through very fertile provinces, had long been the target of Mazarin's predecessor, Cardinal Richelieu, who, as prime minister of Louis XIII, had waged 14 years of war to acquire key territories along the High Rhine, with the presumption that the Rhine River was a God-given "natural border of France." This foolish idea stemmed from the days of the Roman Empire, that is, from the same imperialist outlook that was to be Louis XIV's folie des grandeurs, and was to become the pretext for Napoleon Bonaparte's mad imperial conquests, a century later. The imperial Roman historian Strabo had concocted the geopolitical delusion whereby "an ancient divinity had erected mountains and traced the course of rivers in order to define the natural borders of a people," and whereby, consequently, the Rhine River had to be viewed as a natural border of France.

The Rhine: Boundary, or Corridor?

However, that was not the view of Mazarin. He saw the Rhine River as a great economic project rather than a way to grab more territory. It was a natural communication canal within German territory, a corridor of development. But it was unfortunately being commercially misused by river princes, who were going against their own best interests by imposing such outrageously expensive tolls, that tradesmen preferred using alternative routes, which had become more to the advantage of the Venetians, the Dutch, and the English, than to the German people themselves. This had to be changed.

According to the German historian Hermann Scherer, "The expansion of Amsterdam and of the Dutch market had given the last blow to the ancient commercial greatness of Germany. The Rhine River and later the Escaut, were closed to the German people; an arbitrary system of rights and tolls was established, and that became the end of the wealth and prosperity in the heart of Europe. The defection of many Hanseatic cities from the interior, and the diminishing foreign trade of the Hanse, destabilized the internal commerce and the relationship between the northern and southern regions of Germany. Add to this, the interminable wars, the religious fights and persecutions, and on top of all of this, the addition of custom barriers established under all sorts of pretexts, and for which the smallest princes of the empire added a cost as if it were an essential attribute to their microscopic sovereignty."[1]

Each region was measuring its "sovereignty" by the power to raise Rhine customs fees. The interruptions of the trade traffic, between southern and northern Germany, were bringing the German economy to a halt. This became particularly disastrous for Braunschweig and Erfurt, while Frankfurt-am-Main and Leipzig were barely able to stay afloat thanks to their annual fairs. The very geographic situation of Germany required precisely the opposite: that it free itself of the burden of custom barriers, and open all of its internal mini-borders for anyone who wanted to trade in and out of the country, at low cost, not only north-south, but also east-west. Such were the conditions that Mazarin was attempting to address during the 1640s negotiating period of the Peace of Westphalia.

Fair Trade on Europe's Rivers

Mazarin conducted a thorough study of the entire Hapsburg Empire River system, including the region of Poland. He established a complex intelligence network from among his German allies, to report back to the French negotiators who were involved in the preliminary negotiations for the Peace of Westphalia, in Munster, and to inform them on how many German cities would be willing to increase their freedom within the Empire by collaborating with France. Mazarin examined closely the potential for a north-south expansion of trade and commerce of goods being produced along all of the rivers of the Empire (see Figure 1).

Source: EIRNS.Three centuries of development, and integration by canals, of river transport in Europe, stemmed from the initiatives and public credit projects of France’s Cardinal Mazarin and Jean-Baptiste Colbert in the 17th Century. This development allowed the Peace of Westphalia, the founding treaty of the era of sovereign nation-states, to take hold and end 140 years of religious warfare. These river corridors of development featured the east-west infrastructure canal projects of the Grand Elector (1669) and of his son, Frederick the Great—known today as the Mittelland Canal. Source: EIRNS.Three centuries of development, and integration by canals, of river transport in Europe, stemmed from the initiatives and public credit projects of France’s Cardinal Mazarin and Jean-Baptiste Colbert in the 17th Century. This development allowed the Peace of Westphalia, the founding treaty of the era of sovereign nation-states, to take hold and end 140 years of religious warfare. These river corridors of development featured the east-west infrastructure canal projects of the Grand Elector (1669) and of his son, Frederick the Great—known today as the Mittelland Canal.Furthest east, on the northeastern border of the Hapsburg Holy Roman Empire, Mazarin studied the potential of the Vistula River going through the Polish regions of Silesia, Mazovia, and Eastern Prussia (today Poland), and discharging itself into the Baltic Sea near Gdansk. That river provided for Gdansk, all of the riches coming from all of these regions, and could make it the major port city of Poland.

Secondly, he recorded the fact that the Oder River, which also discharges itself into the Baltic Sea, if all of the production of trade and commerce from the Brandenburg, Silesia, and Pomeranian plains flowed into the city of Szczecin, could transform that city into a major international port city.

Thirdly, the Elbe River, which starts in Bohemia (today the Czech Republic) after having gone through Saxony and Brandenburg, then flows into the North Sea northwest of Hamburg. Mazarin noted that most of the goods coming from the provinces of Lower Germany also flowed northwestward past Dresden, Magdeburg, and Leipzig. Those cities could improve their economic situation by offering commerce houses for transshipments of regional goods to foreign countries.

Fourthly, Mazarin was given a report that the Weser River, which also flows through the fertile regions of Middle Germany, could be provided with a number of canals acting as import and export channels, to make the Weser city of Bremen into a significant port.

Fifth, Mazarin saw another expansion of north-south trade by way of the Ems River, which crosses Westphalia, and brings all of the trade and commerce from Munster and the North Rhine region into a north-south axis opening to the North Sea.

And furthest west, Mazarin studied the Rhine River as the most economically viable communication channel among Switzerland, Germany, France, and the Netherlands, connecting Mulhouse, Strasbourg, Mainz, Bonn, Cologne, and carrying a great amount of trade from Alsace Lorraine, the Swiss Counties, Baden Wuerttemberg, and the Rhineland Palatinate, to its exit to the sea through the cities of Rotterdam and Amsterdam.

Mazarin saw that the surest way to bring about peace was to develop the general welfare of the German people, by developing, for their greatest advantage, the cities located at the mouths of, or along, these rivers. Thus, those war-torn regions of the Empire could be rescued and rebuilt, by rebuilding all of the devastated regions. He considered this the way to counter the British-Dutch mercantilist control over key cities of the Baltic and North Seas.

In 1642, Mazarin summoned his negotiators at Munster to announce and circulate everywhere, that the precondition to the peace negotiations was to forbid the creation of new tolls along the Rhine River. The proposition was written as follows: "From this day forward, along the two banks of the Rhine River and from the adjacent provinces, commerce and transport of goods shall be free of transit for all of the inhabitants, and it will no longer be permitted to impose on the Rhine any new toll, open birth right, customs, or taxation of any denomination and of any sort, whatsoever."

The fact that the injunction included the mention "and from adjacent provinces," proposed to bring fair trade and economic expansion deeper into the heart of Germany.

Centuries of Canal-Building

Under the protection of the French, as the guarantor of the Peace of Westphalia, the different princes of the Empire were able to establish a whole series of Houses of Commerce in Huningue, Strasbourg, Mannheim, Frankfurt am Oder, Coblenz, and Cologne. Thus, Mazarin's plan to build the nation-state of Germany economically, began to take shape. With goods produced from France, Lower Bavaria, High Palatinate, Swabia, and so forth, the river communication system began to revive the economies of the cities of Huningue and Strasbourg, as well as give access to Switzerland and to the extended centers of Austria.

The economic development was to go further by access to the seventh and longest river, the Danube, expanding the import-export trade of goods to and from Bavaria, Austria, Hungary, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldavia, all the way East to the mouth of the Danube in the Black Sea.

As early as 1642, Mazarin had singled out 28 primary cities along the Danube River alone. It is from this standpoint that a new understanding began to emerge from the rubble of war in Europe, capable of creating thousands of jobs and new markets along the main rivers of the Empire. It was under Mazarin and Colbert that the idea of a Rhine-Main-Danube canal began to be considered as a feasible project, a corridor of development only completed three centuries later, connecting the North Sea to the Black Sea.[2]

By the time a number of Electors and princes began to realize that Mazarin's project was entirely to their advantage, and decided to modify their allegiance to the Emperor, war had reduced the German people from 21 million to only 13 million as of 1648. Without peace, European civilization was going to be destroyed.

On the other hand, the Venetians saw that Mazarin was accelerating the process of negotiations in Munster, and that his economic initiatives with the German Electors were beginning to gain some momentum. Venice and the Hapsburgs saw the paradox—the more you increase economic freedom within the Empire, the more you are destroying that Empire itself—and smelled their danger. The more the German leaders were won over to the principle of "the Advantage of the other" (especially since they were "the other"), the closer they were to replace the predatory Empire by nation-states. This principle had such a corroding effect on the minds of the Venetians and the Hapsburg Emperor, that they were ultimately forced to accept the conditions set by Mazarin for the Peace of Westphalia, which was signed on Oct. 24, 1648, in Osnabruck for the Protestants, and in Munster for the Catholics. (See Pierre Beaudry, "Peace of Westphalia: France's Defense of the Sovereign Nation," EIR, Nov. 29, 2002.)

Colbert and the Birth of Political Economy

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-83) was, without a shadow of a doubt, the greatest political economist and nation-builder of the 17th Century, and his ideas and influence have determined the entire course of development of all modern nation-states, including the United States of America, since the Treaty of Westphalia period. Initially promoted as Steward of the household of Cardinal Mazarin, Colbert later became Comptroller General of the Finances of France during most of the reign of Louis XIV. Colbert was the first world leader to successfully apply the new principle of Westphalia to economics, the which would later be followed successively by Gottfried Leibniz, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Quincy Adams, Henry Carey, Friedrich List, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr.

Colbert's seminal contribution to a humanist republican conception of political economy was initially reflected in France's historical fight to liberate the peoples of Europe from the predatory control of the Austrian Hapsburg Empire, and from the central banking role of the Venetian and Dutch oligarchies. Colbert applied the principle of the Peace of Westphalia—that is, the principle of "the Advantage of the other"—to a grand design of economic development of France itself.[3]

For Colbert, the most important asset of the common good, and the most powerful enemy of war itself, was the development of infrastructure projects. Colbert carried the principle of benevolence of Cardinal Mazarin into large-scale economic development projects. If he was the farsighted forerunner of Leibniz, of Franklin, and of LaRouche, it was because his towering figure stood on the shoulders of Jeanne d'Arc, King Louis XI's creation of the nation-state of France, King Henry IV (1597-1610), Henry's minister the Duke of Sully, and Cardinal Mazarin. All were the most powerful enemies of British-Dutch-Venetian free-trade and "central bank" liberalism. The very name of Colbertism, dirigism, still rings as anathema in the ears of the British-Dutch oligarchies today. In fact, any economic outlook organized by a strong centralized government that favors the common good through great public works, stems from Colbertism, and is anathema to British-Dutch monetarism, especially to the Dutch East India Company.[4]

The Industrial Commonwealth Policy

Jean-Baptiste Colbert did not come from a noble family, as many historians have falsely claimed. He was the son of Nicholas Colbert and Marie Pussort, a family of honest merchants, who had traded in Reims and in Lyon from 1590-1635. This period was the turning point for French economic development, with the upsurge of manufacturing under Henry IV and his great advisor, the Duke of Sully. Nicholas' brother, Odart Colbert, was a trader in Troyes, working with an Italian banker partner, located in Paris, by the name of Gio-Andrea Lumagna, with whom he had developed an excellent commerce in draperies, bolting-cloth, linen, silk, wines, and grains, which they produced in France and traded in England, the Low Countries, and Italy. Jean-Baptiste worked a few years in Lumagna's bank, until 1649, one year after the Treaty of Westphalia was signed, when Lumagna became the personal banker of Mazarin, and recommended that Colbert become the Cardinal's household manager. The meeting of such great minds foreshadowed a true French revolution.

Looking at Colbert from British and some American history books, one would be convinced that he was a mercantilist free trader. But anyone identifying Colbert as a mercantilist has to be either totally ignorant or a British agent, at best. The British hated Colbert precisely because he was not a mercantilist; he was feared because he was a humanist nation builder. Colbert's policy was to undertake and fund, from the royal coffers of Louis XIV, all forms of industry, mining, infrastructure canal building, city building, beautification of the land through Ponts et Chaussées (Bridges and Roads), Arts et Métiers (Arts and Crafts), including the promotion of all aspects of science through the creation of the Royal Academy of Sciences under the leadership of Christian Huygens.

Thus, clearly, Colbert's idea of "the Advantage of the other" was aimed at benefitting future generations. It precluded primarily the idea of competition, a politically correct term for enmity.

Colbert's industrial protectionist system is generally known for four major reforms that marked the beginnings of the modern industrial nation-state: 1) He organized and funded a system of industrial corporations and infrastructure projects that provided job security for all types of skilled and non-skilled labor, that is, workers of all types of arts et métiers; 2) He established protectionist measures for all standardized French clothing products, such that no dumping of foreign goods was allowed in France, except at very high cost. Colbertism became synonymous with protectionism; 3) He funded and supported population growth, considering that war and ignorance were the two main causes of population reduction. He believed that the "government had to take care of its poor," and that its role was to foster the increase of the population density of the nation; and 4) He accompanied industrial measures with a reform of civil justice that became the first Civil Code of France, lasting 130 years until it was destroyed by the imperialist code of Napoleon at the turn of the 18th Century.

These four points were enforced with total energy and determination, and with the full backup of the King of France. In other words, the entire Colbert system of nation-building was based on state-controlled industrial development, combined with closely selected and productive private initiatives. Colbert looked at the nation as a farmer cares for his farm: The entire territory of France was meant to become the land where the common good was to grow unimpeded. He protected it, showered it with public funds, enriched it, and let others reap its beautiful fruits. He cultivated the common good by weeding out the privileges of aristocracy; he encouraged new industries and funded population growth by creating tax incentives and special bonuses for married couples. He put protectionist barriers all around France, against British, Dutch, and Belgian dumping. In one word, Colbert became the champion of skilled labor and the sworn enemy of commercial aristocracy, which had been living off their privileges as the feudal aristocracy had done, during the past centuries.

So, Colbert re-established the priority of the "common good, the "Commonwealth" of Louis XI."

The following case suffices to make the point.

During the 1660s, there persisted a three-century-old privilege that dated back to the shameful 1358 edict of Charles V, that stated that the laws of commerce "are made to profit and favor each craft rather than the common good."[5] Colbert turned this on its head, instituting his first Edict on April 8, 1666, which was made to secure all of the manufactures and factories of the kingdom for the benefit of the common good. From that day on, Colbert wrote hundreds of measures and regulations until the entire garden of France began to bloom again, after the devastation of the religious wars.

From 1666 on, Colbert not only had a total control over the production of all French clothing goods, but he instituted a master's degree for the work force, in order to improve the quality of all manufacturing products.

Colbert invested about 5,000,000 pounds a year from the coffers of the King in new manufacturing investments. This money went for improvements in technology, for improving skills of the workers to raise the quality of the products, and for incentives to population growth. A lot of the new technologies were imported from Italy, Holland and elsewhere, to improve the quality of tapestries, linens, silks, etc.; but most of the improvement was done on location. Historian Pierre Clement reports that Colbert "stopped at nothing in order to fortify the new establishments; each dyeing manufacturer received 1,200 pounds of encouragement; the workers who married girls of the locality where they were employed, would receive a bonus of 6 pistoles, plus 2 pistoles at the birth of their first child. All apprentices were given 30 pounds and their own tools at the end of their apprenticeship. Lastly, the tax collectors were ordered to give a tax exemption of 5 pounds for those employed in certain more privileged manufactures."[6]

Colbert further established that all workers who married under the age of 20 were exempt from taxes (tailles and other public charges) for a period of five years, and four years if they married at 21. The very same advantages were extended to older workers who had 10 children, including those who died in combat. As of July 1667, all workers who had 10 children could receive a pension of 1,000 pounds a year, and 2,000 pounds a year, if they had 12 children. After 16 years of such a regime, from 1667 to 1683, the French population had reached a level of 20,000,000, the largest national population in all of Europe. The policy was called Colbert's "revenge of the cradles" (revanche des berceaux). The same policy was established in the French colony of Canada.

Colbert's Reform of Justice

The reform of the civil justice system, in 1669, was one of Colbert's greatest and most enduring achievements. It was so efficient and complete that it became accepted as the Civil Code of France for a period of 138 years, until the feudalist faction of the French oligarchy replaced it with the Code Napoleon in 1807, and turned France, one more time, back to a fascist imperial police state. The Code Napoleon rules France to this day.

In the spirit of Mazarin, Colbert was able to launch a great offensive against the very powerful aristocracy of France, and go against all odds; that is, against both public opinion and backward local prejudices, to implement his reforms. He established a most sweeping reform of justice, succeeding in accomplishing what even the great Sully before him had attempted, but was not able to do. Colbert systematically extirpated venality (venal office, the practice of buying public offices and profitting from them). He established a system of state counsellors to replace the old civil order of Roman law, and totally transformed the traditional, regional, customs law. One of his most effective administrators and collaborators was the King's Counsellor to the Parliament of Toulouse (Court of Justice), the famous mathematician Pierre de Fermat.

As early as the reign of Louis X (le Hutin) (1314-16), judicial offices had been sold to the nobility at a minimal fee paid to the King, but which brought incredible profits to the office holders. This was done as a matter of course, under the absolutely trusting axiomatic assumption that "the monarchical system was based on honor and that the nature of honor is to have for Censor, the entire universe" (Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Law). This being the case, why should anyone raise an eyebrow about the "honesty" of any member of the Court to whom the public good was entrusted? As Montesquieu himself argued, after all, "No one believes he is lowering himself by accepting a public function."

However, the heart of man being everywhere the same, Colbert understood very well that, under any government, at any time, the honor of fulfilling the duties of an office of state can always be mixed with a certain amount of contrived interest, which brings justice to tilt its balance on one side rather than the other. For example, public opinion had it, in those days of the monarchy, that the rich were not only better off, but also better educated than the rest of the population, and because of that, they had more dignity and impartiality; and since paying for their public office was a way to bring in money for the King, they demonstrated themselves less venal than others, and therefore should not pay any taxes; because the investment of their capital was obviously benefitting the kingdom more than did people with less money, and whose contribution to the common good was less than their own, and should therefore be made to pay taxes more readily. And, that is the way the balance of justice tilted for centuries.

The most famous example of abuse of public trust during that period was known as the Fouquet Affair, the scandalous case of the Superintendent of the Finances of King Louis XIV. In November of 1661, Colbert forced Nicolas Fouquet to be brought before the tribunal for having stolen an immense fortune from different public offices, and from the treasury of the King.

Acting as a central banker, and borrowing for the King and Mazarin—to whom bankers were told not to lend any money—Fouquet had been playing the interest rates game in his favor; and since he had all of the controls to blur the differences between public and personal interests, he was able to hide a huge fortune, until Colbert got a whiff of it. In one instance, Fouquet had managed to reassign to his own bank account the values of a loan that was never made, but for which the State "repaid" him 6,000,000 pounds. During the last four months before his trial, he had managed to siphon off a total of 4,000,000 pounds in amounts of between 10,000 to 140,000 pounds that he stole from the different tax-farms of the Charente, Pied-Fourche, Lyon, Bordeaux, the Dauphine, etc. Fouquet had even prepared himself a fortified refuge in Belle-Isle, in case of disgrace.

In 1661, the government brought him to trial, where he was found guilty of massive embezzlement. All of his goods were confiscated, he was condemned to exile, and then later imprisoned for life in the fortress of Pignerol.[7]

A Coup d'État Against the Oligarchy

In March of 1661, the 23-year-old King Louis XIV replaced Nicolas Fouquet with Colbert as the Superintendent of the Finances. If Louis XIV was so upset by corruption, it was not because of moral indignation, but because it was taking place under his watch. Colbert recognized that fact and did not miss a moment in applying the principle which Alexander the Great used to get his (indifferent) generals to act effectively.

Never was there as effective and universal a minister as Colbert, during the entire history of France. Formed at the school of Sully and Mazarin, Colbert served during 22 years successively as the Superintendent of Finances, Superintendent of Building Trade, Comptroller General, Secretary of State, Secretary of the Navy, Minister of Trade and Commerce, and last but not least, the equivalent of a Minister of Sciences and Technology. He made profound reforms in all of these public domains, including Criminal, Commercial, Police, Fine Arts, Water and Forest, etc.

After the scandalous trial of Fouquet was over, Colbert became a popular hero, and was given the green light for the creation of a Chamber of Justice that he had already proposed to Mazarin, back in 1659. This Chamber of Justice was composed of the different presidents and top counsellors of the Parliaments of Paris, Toulouse, Grenoble, Bordeaux, Dijon, Rouen, etc. In all, 27 judges were commissioned by Colbert, to clean up the biggest financial mess the nation had ever seen. Colbert's edict, which circulated in every city of the kingdom, stipulated that all of the financial officers of the nation who had been at their posts since 1635 were required to establish a justification for all of their legitimate goods, including their inheritances, the acquisitions they had made, the amounts given to their children for anything from weddings to acquisition of offices. If the information were not given to the attorney general within eight days, all of their goods and properties were to be confiscated.

Colbert established all sorts of means to force the truth out in the open. The edict stipulated that the King would reward an accuser with the value of 1/6 of the fine given to anyone convicted of fraud, financial abuse, or embezzlement. On Sunday, Dec. 11, 1661, as well as on the following three Sundays, Colbert had all of the curates of the Paris churches make the announcement that the parishioners, under threat of excommunication, were obliged to speak out about all known financial abuse in their parish.

The first operations of the Chamber of Justice had created total panic throughout Paris. Friends of Fouquet, such as Vatel, Braun, and Gourville, left for London; others were tried and sentenced. After a few financiers were sent to the Bastille prison, the whole nation began to realize that Colbert really meant business. Then a lot of people began to be identified to the Chamber of Justice.

After Colbert made a public showcase of this insane system, the idea of buying a public office became so unpopular that people circulated a Colbert quip that said: "Each time the King creates an office, a new idiot is created to buy it." The reforms were so sweeping that, in only a few years, a total of 419,000,000 pounds was recovered from the income of venal offices, and no fewer than 40,000 noble families were affected by this axiomatic change.

All of those funds were then invested in Colbert's program of development of new industries. Slowly, but surely, the balance of justice began to tilt back toward the common good.

The Royal Academy of Sciences

Louis XIV visits the astronomy room of the Royal Academy of Science. Louis XIV visits the astronomy room of the Royal Academy of Science.

Colbert’s Royal Academy’s study of determination of longitude caused a major advance in the geographic knowledge of Europe by improving the accuracy of maps and sailing charts through the introduction of new geodesic studies (the Cassini maps). The result of three generations of work by the Cassini family was the first truly accurate map of France and its provinces, in 1744

Colbert presenting Riquet’s plan to build the Canal du Midi, to Louis XIV in 1668, when it was approved.The greatest achievement of Colbert was the creation of the Royal Academy of Sciences and its technological projects. This was not just another academic teaching institution, but rather, a research center for scientific and technological development that had the mission of creating innovations in specific areas of scientific activities: to improve economic development in the fields of astronomy, chemistry, optical physics, geometry, geography, industrial engineering, canal building, agriculture, and navigation. Each area was to be oriented toward technological advances through the application of new discoveries of physical principles. This Colbertian Academy of Sciences became the model institution from which Gottfried Leibniz later created his academies in Berlin and St. Petersburg.

In 1662, Colbert's good friend and collaborator, the Toulouse Counsellor of Parliament and mathematician Pierre de Fermat, joined Blaise Pascal, Gilles de Roberval, Pierre Gassendi, and a few others, to form the core of a society that met regularly, and in private with Colbert, in the Royal Library, until the time the Academy was to be officially located in the Louvre Museum in 1699. Scientists and mathematicians from all over Europe were invited to join the new institution—all of whom had been challenged, in 1658, by the young Pascal into discovering a geometric construction for determining the characteristics of the cycloid curve.

The offers of salaries and pensions were very attractive, and the prospects of collaborating with the best scientists of Europe were even better. Colbert sent out personal invitations to the Dutch astronomer and geometer Christian Huygens, one of the few to have solved Pascal's cycloid problem; to the Italian astronomer and civil-military engineer Gian Domenico Cassini; to the young Danish astronomer who was to prove the speed of light, Ole Römer; to the German mathematician Tschirnhauss; to the German astronomer Johann Hevelius; to the Florentine geometer Vincent Viviani; and even to the British mathemagician Isaac Newton. Huygens, Cassini, and Römer immediately accepted the invitations; others accepted a little later.

On Dec. 22, 1666, Huygens was nominated as the President of the Royal Academy.

Colbert believed that the most important means of securing the future of France was to persuade the young King to fund and support great scientific and technological projects that would both increase the power of the nation internally, and extend its contributions abroad. There were several great projects of note. One was the determination of longitude, a project as old as the Platonic Academy of Alexandria, following through the astronomical discoveries of Erastosthenes and Hipparchus. This caused a major advance in the geographic knowledge of Europe by improving the accuracy of maps and sailing charts through the introduction of new geodesic studies (the Cassini maps), a precursor to the revolutionary study that Carl Gauss made two centuries later. This effort resulted in the first accurate knowledge of the Earth's geography. Parallel to it, was the creation of the Paris Observatory, and the successful grinding of very powerful telescope lenses, designed and hand-polished by Huygens himself.

The second and most far-reaching scientific breakthroughs came with new discoveries in the field of optical physics, especially the revolutionary discovery of principle by Römer in the determination of the finite speed of light; by Huygens in the discovery that light propagates in spherical waves; by Fermat in demonstrating the principle of least time in light refraction; and by Leibniz with the revolutionary application of his least action principle to optical processes by means of his calculus.[8]

A third project, involving the special collaboration of Huygens and Leibniz, was the development of a steamboat invented by Denis Papin.[9] In 1673, Leibniz had also built a working model of a calculating machine with the collaboration of the Royal Librarian Pierre de Carcavy, and Huygens. It became such a success that he was immediately asked to build three models, one for the new Observatory, one for the King, and one for Colbert.

After Colbert died, in 1683, a new witch-hunt began against the Protestants of France, and the Academy suffered greatly when, in 1685, under the revocation by Louis XIV of the Edict of Nantes, which had guaranteed freedom of religion for Protestants since Henry IV, Ole Römer and the other "undesirable Protestant," Christian Huygens, were forced out of the country. The Academy survived for a hundred years under Fontenelle, Condorcet, and Lavoisier, but it was ultimately destroyed in 1793 by the Jacobin counter-revolution.

Continental Challenge to the 'Sea Powers'

But the most immediate and powerful industrial result of Colbert's Academy project, was the realization of the greatest hydraulic engineering masterpiece of the era—the Languedoc Canal.

The Languedoc Canal (built 1667-81), known also as the Canal du Midi, was a typical example of how Colbert, and his engineer protégé, Pierre-Paul Riquet, realized the Mazarin principle of the Peace of Westphalia. In fact, the Languedoc Canal represented, for several hundred years, the most advanced form of hydraulic technology in the world, and the most economical route for the transport of merchandise between the northern nations—Sweden, Denmark, Poland, Northern Germany, Belgium—and the southern nations of Italy, Greece, Venice, the Balkan States, Turkey, Africa, and the Orient. The construction of the canal provided a short-cut of 240 kilometers (145 miles) across France, saving 3,000 kilometers represented by the detour around Spain; and an economy of taxes, by avoiding the Hapsburg Empire tolls at the choke point of Gibraltar.

Had the British and Dutch monopolies of the time been reasonable in their trade negotiations with France, this fair-trade system would have also brought down their costs of goods.

As far as external commerce is concerned, Colbert always extended the same fair trade policy to all nations, including the liberal free-traders Holland and England. But, neither the liberal Dutch nor the English accepted Colbert's policy of fair trade. That is why Colbert had to send his toughest ambassador to London: his own brother, Charles Colbert de Croissy, the same who had served Mazarin as ambassador to Vienna in 1660.

After a number of tough negotiating years, in which Charles Colbert was forced to make a certain number of sacrifices, an amusing point of contention came up that could serve as a precursor to the antics of Lewis Carroll in Alice in Wonderland. In 1669, Colbert reminded his ambassador "not to be duped" by British pretentions on the high seas; the issue related to the British Admiralty requesting the right to be saluted first on all of the seas of the globe.

In a letter dated July 21, 1669, Colbert wrote his brother a note in which he stated: "As far as the Ocean is concerned, even though they [the British] are the more powerful, we have not, until now, come to the view that their pretended sovereignty has been recognized; therefore it pertains to the common good of the two nations, and of the interests of the two kings, to establish this parity on all of the seas.... As for the treaty on commerce, the ideas of Lord Arlington are very reasonable, since they tend to establish a reciprocal treatment between the two Kingdoms."

Colbert ended up recommending that "salutes" be considered optional; but the liberal free-trade policy of England remained on a steady course.

The control of sea-lanes by the financial oligarchies of maritime powers such as the Venetians or the British-Dutch East India company monopolies, was being challenged by Colbert's emphasis on a dirigist continental infrastructure project, as the growth principle for economic development of sovereign nation-states. The same principle is applicable today, with the LaRouche Eurasian Land-Bridge concept, in which all European governments see the benefit of Asiatic nations as the natural outlet for their export of technologies. The soon-to-be signed agreements for the extension of the German-Chinese magnetic-levitation Transrapid train, already commercialized in Shanghai since Jan. 1, 2003, are a prime example of this type of fair trade, technology-sharing policy.

Economics of Generosity: The Languedoc Canal

The Languedoc Canal Project was the greatest project of the 17th Century: a triumph of engineering skills, built by a self-made geometer-engineer, Pierre-Paul Riquet. This Herculean task, which had been deemed impossible since Roman times, was a gigantic water infrastructure work that Charlemagne himself had dreamed of building. In 1516, François I had asked Leonardo da Vinci's advice on the feasibility of a canal in that region of France. Leonardo actually spent his last years in Amboise, studying possible canal connections between the Loire and the Seine Rivers. Other studies had been made for a canal through the Languedoc region during the reigns of Charles IX, Henry III, Henry IV, and Louis XIII.

Source: EIRNS.The Languedoc Canal bridging the Atlantic and Mediterranean Seas across southern France, built between 1667 and 1681, had been desired for centuries before that. It required solving the problem of a water source, in order to flow in two directions, east and west. It was the greatest civil engineering project of the 17th Century, contributing to shifting commerce from “free-trade” control of sea lanes toward fair-trade development in the interior of the continent. The project became a model for much larger continental projects such as the Rhine- Main-Danube Canal built during the 20th Century. Source: EIRNS.The Languedoc Canal bridging the Atlantic and Mediterranean Seas across southern France, built between 1667 and 1681, had been desired for centuries before that. It required solving the problem of a water source, in order to flow in two directions, east and west. It was the greatest civil engineering project of the 17th Century, contributing to shifting commerce from “free-trade” control of sea lanes toward fair-trade development in the interior of the continent. The project became a model for much larger continental projects such as the Rhine- Main-Danube Canal built during the 20th Century.It was not until Colbert that a solution, to what had become known as the impossible Canal du Midi, was discovered.

There were four main reasons for the construction of this great canal. First of all, coming out of the Thirty Years' War, this canal project corresponded to a greatly needed change of strategy and of political economy for the entirety of Europe. As we have said, the crossing of France by canal, between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, provided French and allied ships with a strategic by-pass of Gibraltar, an area that had become very dangerous, and quite costly, during the interminable wars with Spain and the Austrian Hapsburg Empire.

Secondly, the canal set the example for joint public and private infrastructure development projects along waterways of any nation, providing improvements for land-locked areas, and opening them up to increasing exchange of cultures with other regions and other nations. Moreover, both the King and Riquet were to receive a regular income stream from low-cost tolls. The canal was going to pay for itself in a very short period of time, and provide for a small margin of profits for repairs and for the introduction of new technologies. Riquet made it explicit that he had no intention of building the canal for the purpose of financial gains.

Thus, the Peace of Westphalia trade and commerce studies, made earlier by Mazarin for the benefit of the seven river regions of the Hapsburg Empire, became a renewed focus of interest. The canal was going to create the greatest import-export capabilities ever imagined for that time.

Thirdly, the canal provided for an extraordinary increase of economic activities in the Province of Languedoc itself, where High Languedoc wheat production could be shipped easily eastward to the wheat-starved Lower Languedoc region. In exchange, the Lower-Languedoc production of excellent wines could be easily shipped westward, while the linen and silk goods of Lyons could also travel the same route.

This corridor also provided the entire region from Toulouse to Beziers with the development of new olive groves, vineyards, greater expansion of granaries in the Lauragais region, new trade companies and mills, and prospects for mining. The more farsighted citizens of Castelnaudary, for example, even paid Riquet to divert the canal toward their town. Riquet had also projected the creation of new towns along the canal route.

Fourthly, and not least, the entire course of the 240-kilometer-long canal was going to be carved within one of the most beautiful landscapes in the world, and was going to be covered with 130 arched bridges built by the "beautifying engineers" of the Ponts et Chaussées. Colbert and Riquet were both of the conviction that if it is beautiful, it is useful!

Riquet's 'Parting of Waters' Paradox

However magnificent the idea was, and however great the advantages were anticipated to be, all of the proposals to link the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea with a canal, during a period of 1,000 years, were demonstrated to be totally impracticable, and plans presented by the best engineers in the world, were rejected each time.

There were two ostensible reasons why this project was considered to be impossible. One was that the two rivers flowing respectively into the Atlantic and the Mediterranean—the Garonne and the Aude—could not be connected because of difficulties of terrain between them; and the technology to raise any great quantity of water upwards of 190 meters above sea level did not exist. The other reason was that there was no other visible source in this quasi-desert region of Provence that could provide the canal with the required amounts of water.

However, there was a third and more profound and subjective reason. All of the canal plans were rejected because none of them reflected the necessary discovery of principle that would make it work. Just as Brunelleschi had discovered the physical geometric principle of the catenary for the erection of the "impossible" Dome of the Florence cathedral, Riquet had discovered the required physical geometric principle that solved the problem of the "impossible" Languedoc Canal.

Pierre-Paul Riquet (1604-80) was a descendent of a Florentine family by the name of Arrighetti, changed to Riquetty, and then to Riquet. His father, the Count of Camaran, who was a public prosecutor for the Crown, educated his son in public management and got him a post in the administration of Bezeirs in the Languedoc region. As a young man, Riquet attended the council meetings of the Counts of Languedoc with his father, at which there were several presentations of canal projects "linking the two seas." After witnessing several unsuccessful debates on the question, Pierre-Paul Riquet became passionate about finding a solution to this "impossible problem."

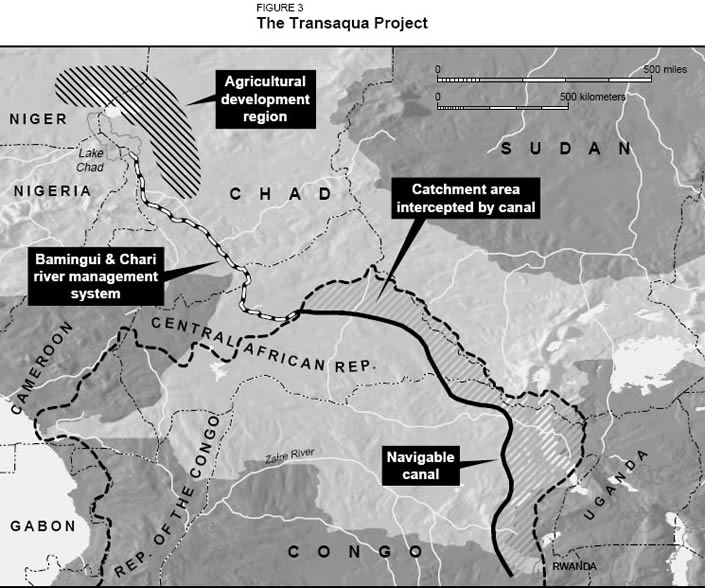

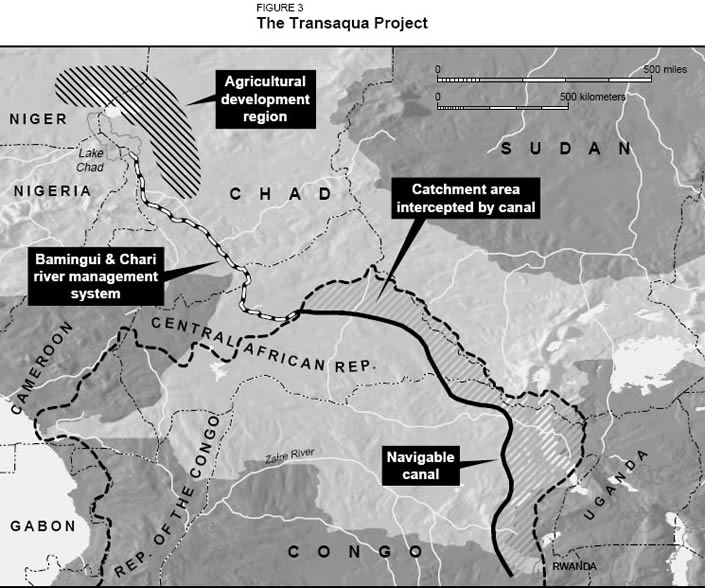

The same principle applied to a proposed infrastructural great project today: the plan to create a canal to recharge the disappearing Lake Chad in Africa’s Sahel, by draining part of the catchment area of the Zaire River’s great flow. The urgent project will not be done without the kind of public credit strategy pioneered by Colbert, known since then as “dirigism.” The same principle applied to a proposed infrastructural great project today: the plan to create a canal to recharge the disappearing Lake Chad in Africa’s Sahel, by draining part of the catchment area of the Zaire River’s great flow. The urgent project will not be done without the kind of public credit strategy pioneered by Colbert, known since then as “dirigism.”Since Riquet did make the discovery, and built the canal, the following description must hold some truth, with respect to the discovery which must have happened in the mind of this great man.

One day, a paradox must have struck Riquet; an anomaly in the form of a simple question must have struck him: "How can the flow of a canal go in two directions at once?" In a way, it was a very simple question; but none of the other engineers over centuries, who had looked instead for ways to connect up the river courses of Languedoc, seemed to have approached the problem quite this way.

That the question was vital to Riquet, is shown by the fact that he had a drawing made, some time after his discovery, to commemorate a pedagogical reconstruction of his principle. It showed himself demonstrating to the Commissioners of the King and of the States, the solution to the problem that he had called—in a reference to the Moses miracle at the Red Sea—"the parting of the waters."

The drawing simply shows how a stone, placed before the water rising from the Fontaine La Grave, on the Plateau de Naurouze, divided the stream of water into two opposite directions, one part flowing west, toward the Atlantic Ocean, and the other flowing east, toward the Mediterranean Sea. Riquet's paradox had become a metaphor for what he then began to call the "canal of the two seas." He had generated a solution in principle to the "impossible" canal.

The "canal of the two seas" became his life's mission. Year in and year out, Riquet made experiments, created model projects on his own land, and studied different locations around Montagne Noire, travelling the distance many times, searching for the solution to the source of water that would connect the two seas. If the illustration of the "parting of the waters" showed the principle, the fulfillment of that principle was going to be another matter altogether.

There was only one ideal spot in the entire expanse between the two seas where Riquet's principle could be applied, and that had to be precisely at the highest point that divided the entire region between West and the East. And when Riquet found that unique spot, there was no source of water at that location.

The Engineering Task

It was not until the ripe age of 58, after serving the government of Colbert, as a comptroller of the Salt Tax (gabelle) in the region of the Languedoc for 20 years, that Riquet confirmed his hypothesis by conducting a crucial experiment. By that time, he had enough of a personal fortune to invest in his "grand design," as he called it. Riquet asked Colbert to let him resign, and to hire him as chief engineer of the canal project. Colbert agreed, and got his Toulouse Counsellor, Pierre de Fermat, to authorize the project that was going to be built in his jurisdiction.

Riquet was able to solve his paradox by demonstrating how the result of its resolution was going to express itself in the increase of man's mastery over nature, a definite increase in potential relative population density. He knew beforehand, that the construction of the canal would create an expansion in markets inward and outward, which would result especially in the increase of French production of wheat, wines, and fabrics being exported toward England, Sweden, Germany, Holland, Italy, Greece, and so forth.

A Languedoc teacher, Philippe Calas, living today near Beziers, shows on his website called "Le Canal du Midi en Languedoc," how Riquet tackled the different engineering problems. He writes: "But there was one overwhelming problem facing all of these would-be canal builders: how to supply such an engineering work with water? One part of the route represented no such problem. The section from Toulouse to the Atlantic could be achieved by the canalization of the River Garonne, navigable along this stretch. But from Toulouse at one end of the canal proper, to sea level at the other (Mediterranean end), the canal would have to rise to a summit of 190 meters. How could enough water be found to keep the canal flowing at a constant rate, and at what point should this water be supplied to it in order to distribute it evenly to the western section flowing toward Toulouse and the eastern section flowing towards Beziers?"

And who would be foolish enough to think that such a fantastic source of water could ever be found in the quasi-barren mountains of the Languedoc?

The Languedoc Canal is still in regular use 330 years after its “impossible” construction (here, one of its beautiful bridges carries the canal at Béziers near the Mediterranean terminus). Its revolutionary features included even the lining of the canal with plantain trees, whose leaves Riquet determined would provide a waterproof “cover” for the canal bottom.As soon as he was ready to make his experiment known, Riquet wrote to Colbert, who immediately saw the solution, and was won over to the project. Colbert always appreciated the character of a man who could not be shaken from a true discovery, and he knew he could absolutely count on Riquet to bring the great work to success, if he gave him the necessary back up. The engineering task was to assemble enough water into a catch basin—from what today would be called a "catchment area" of subsurface water—and at the highest altitude, which could supply all of the necessary water to flow with gravity continuously into a westward slope toward the Atlantic and into an eastward slope toward the Mediterranean, each in a controlled manner.

Riquet found several hidden springs and streams in the vicinity of Montagne Noire, less than halfway between Carcassone and Toulouse, which could supply a reservoir to be built at Saint Ferriol. This reservoir of water had to hold a large enough supply of water to feed the canal all year round, including during periods of extreme drought, which occurs regularly in Provence. The reservoir was also to be supplemented by three additional sources—the Sor River, the Alzau stream, and the Fresquel River. A series of secondary basins had also to be constructed, to control the deliveries of the many flows.

Canal and Ports du Midi

In his first testing experiment, Riquet spent 200,000 pounds to build a drainage trench demonstrating to the Council of the State of Languedoc how the whole system would work. At that occasion, on Nov. 27, 1664, Riquet wrote to Colbert saying: "But in this case [the drainage trench experiment], I am putting at risk both my fortune and my honor, and they won't fail me. In fact, it seems more reasonable that I shall acquire a little more of one as well as of the other, when I come out of this successfully. I hope to be in Paris during the month of January next.... And then, Monseigneur, I shall have the honor of telling you, in person, and in a better fashion, all my sentiments on the subject. And you will find them reasonable because I will have established precise propositions that will consequently be in accordance with your wish; and in which case I shall follow my natural inclination of frankness and freedom, and without quibbling."

On May 25, 1665, Riquet was in Paris meeting with Colbert, who gave him his patent papers securing him in his rights of ownership. Two months after, on the last day of July, Riquet wrote Colbert, filled with the excitement of Archimedes coming out of his bathtub. His experiment was a total success! He wrote: "Many people will be surprised to see how little time I have taken, and little expense I have used. As for the success, it is infallible, but in a totally new fashion, that no one ever thought of, including myself. I can swear to you that the pathway I have now discovered had always been unknown to me, regardless of all the efforts I had made in attempting to discover it. The idea came to me in Saint-Germain, which is quite far away, and my musing proved me right about those locations."[10]

By 1666, after Riquet had developed extensive feasibility studies and established the financial conditions for the construction of the entire canal, he got permission from Colbert to begin the first phase of construction. The entire project was going to be built in three phases, and be financed both through private means (Riquet's) and by the State. Phase one, which was to be financed entirely by Riquet himself, included the hydraulic work of a catch basin—the Saint Ferriol reservoir at the foot of Montagne Noire—with a capacity of 6,000,000 cubic meters of water, the largest man-made lake ever built up to that time; and the building of the Toulouse-Trebes section of the canal going west toward the Atlantic. This reservoir was going to supply the water for the entire work. The second phase, to be financed by the State, included the canal section from the reservoir to the fishing village of Cette (today called Set), on the Mediterranean. The third phase, also to be financed by the State, included the creation of a major seaport facility at Set.

Moreover, the canal presented several extremely difficult engineering feats, such as having to go through the Malpas Mountain in an excavated tunnel of 173 meters in length, and then flowing on top of a bridge for several hundred yards over the Ord River. The entire project originally contained 75 locks, took 14 years to build, and cost the royal treasury more than 7,700,000 pounds, not including the 4,000,000 pounds invested by Riquet personally. Louis XIV and Jean-Baptiste Colbert inaugurated the canal at Set, on May 24, 1681.

Although Riquet, who died eight months earlier, had not lived to see his masterpiece of engineering completed, he had lived and communicated to others the joy of immortality, and was comforted in the knowledge that he had brought a great contribution to mankind. At the turn of the 18th Century, the famous military engineer and admirer of Riquet, Marshal de Vauban, made some important improvements and a number of significant additions to the canal. Today, the canal is still in operation, for both trade and tourism.[11]

Riquet had also broken new grounds in fostering "the Advantage of the other" by providing exceptional benefits for his own workers. The Canal Company had a 12,000-man workforce, divided into 240 brigades of 50 men each. These represented the best-paid workers of the period for this type of construction work. Riquet had gotten from Colbert a royal order to pay, for the security of his workers. The salary of 10 pounds a month per worker included inexpensive living quarters, Sundays and religious and national holidays off, plus complete medical coverage and full disability in case of illness. The royal order also stipulated that "those who present themselves must be fit to do the work, not incapacitated in any way, and must not be younger than twenty years of age or older than fifty." Riquet's enemies were very upset, because other workers in the region of Languedoc began to demand similar working conditions.

Riquet's royal charter for the protection of his labor force was the first of its kind in the history of Europe, guaranteeing the equivalent of good "union wages and conditions."

The Principle of Discovery

How was Riquet's canal plan going to guarantee success, when all of the others had failed? How can you guarantee that the LaRouche project of the Eurasian Land-Bridge will succeed, when all free-trade proposals have miserably failed? The answer to these questions lies in the fact that both Riquet and LaRouche understand the principle of discovery. The irony of Riquet's discovery was that, while everybody else was trying to use the waters of two rivers whose flows were contrary, and could not be made to climb up to 190 meters above sea level, Riquet solved the problem by tapping the waters of far away desert streams, up to 65 kilometers away from the canal's path, and sent them flowing into the only spot from which "the parting of the waters" could send the flows down into two directions at once. The idea was brilliant and the fruit of a true genius.

It is amazing how apparently unsolvable problems get resolved, when they are viewed from outside of the domain of sense perception. Riquet's project was so successful, that when Marshal de Vauban visited the site a few years after its completion, he remarked: "There is, however, something missing here: there is no statue of Riquet."

In May of 1788, a year after visiting the South of France, Thomas Jefferson sent some notes about the construction of the Canal of Languedoc to George Washington. Jefferson wrote: "Having in the Spring of the last year taken a journey through the southern parts of France, and particularly examined the canal of Languedoc, through its whole course, I take the liberty of sending you the notes I made on the spot, as you may find in them something perhaps which may be turned to account some time or other in the prosecution of the Patowmac [Potomac] canal." Jefferson's acute interest in the Canal du Midi is one more example showing how the economics of the Peace of Westphalia had found its manifest destiny in America.[12]

Under Colbert's policy, France once again embraced the "principle of benevolence" that Louis XI had institutionalized from the sublime courage of Jeanne d'Arc. The so-called "religious wars" which had decimated Europe for over a century and a quarter, were stopped and overcome. Never, during such a short period as the Mazarin-Colbert reforms, had so much evil been defeated by such a simple and effective principle as "the Advantage of the other," or the common good. Without it, the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, and the era of sovereign nation-states which it launched, would not have been possible.

[1] Hermann Scherer, Histoire du commerce de toutes les nations depuis les temps anciens jusqu'a nos jours, Tôme Seconde (Paris: Capelle, Libraire-Editeur, 1857), p. 548.

[2] The Mazarin plan for developing rivers and canals inside Germany made its way across the empire, and was finally realized under the reigns of the Grand Elector, Frederick William I, (1620-88), the founder of the German nation-state, and his successor, Frederick the Great (1712-86). According to Scherer, op. cit., it was Frederick II who fully succeeded in creating a real internal economic system centered on a whole series of canals that connected the rivers from east to west. After Frederick William I built the great trench that connected the Oder and the Elbe rivers, in 1668, "Frederick II continued the canal works of his predecessor. In Westphalia, the Ruhr was made navigable, and an outlet was created to the saline Unna. The canal of Plauen established the most direct connection between the Elbe, the Havel, and the Spree; the Finow canal connected the Havel and the Oder; the Bromberg canal connected the Oder and the Vistula. These navigable channels soon gave a tremendous impulse to the commerce of the Steps and to the neighboring provinces with the basin of the Elbe, Silesia and Poland, and thus contributed greatly to the rise of Berlin as a commercial city." (Scherer, op. cit., p. 581.)

These canal routes correspond today, to the different sections of the Mitteland Canal crossing Germany from west to east, connecting all of its main rivers from the Rhine to the Vistula and linking the main cities of Bonn, Münster, Osnabrück, Hannover, Braunschweig, Magdeburg, Berlin, and to the Polish city of Bydgoszcz (Bramberg).

[3] This principle of benevolence takes its political roots in the policy of Henry IV and the Duke of Sully, in the aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew's Day religious massacre of 1572. As Sully had emphasized to the King later: "Your intention must be to truly seek all of the means to have them [potentates] live in peace and tranquility among themselves, constantly soliciting them to establish a peace or a truce, whenever there should be contention or diversity of pretentions; and always to endeavor to put forward, with whomever you are dealing, your generous resolution whereby you wish everything for the others, and nothing for yourself" (emphasis added). (Maximilien de Bethune, Duc de Sully, Memoires des sages et royales oeconomies d'estat, domestiques, politiques, et militaires de Henry le Grand, par M.M. Michaud et Poujoulat, Tôme deuxième, Paris, chez l'editeur du commentaire analytique du Code Civil, 1837, p. 151.)

[4] Since the discovery of America and of maritime routes to India, the control of sea-lanes, and the monopoly of world trade by global merchant companies, have been the main function of a few maritime financial oligarchies. They have centered most prominently, during successive periods of history, in the cities of Venice, Amsterdam, and London, from whence they wielded the power of their central banking interests over most of the national economies of the planet. The 17th-Century Dutch East India Company was such a commerce house. It was created on March 20, 1602, for the purpose of establishing a monopoly of trading in the Far East.

The new company was placed under the control of the Duke, William of Orange, in Amsterdam, and was composed of 60 administrators, elected by the shareholders—that is, by themselves—to form a General Estates that became the real behind-the-scenes government of Holland. It was like a parliamentary group composed of six different chambers, each of which was located in Amsterdam, Middelburg, Delft, Rotterdam, Horn, and Enkhuisen. Their control mechanisms were not unlike the European parliamentary system of today, under the Maastricht Treaty and its central banking arrangement. The general business of international trade was put into the hands of a smaller group of seven directors who would meet, several times a year, in Amsterdam, to determine the number of ships to send out, the period of their voyage, the times of their departure and return, and their specific destinations and cargoes. The directors' executive orders had to be obeyed to the letter, and with the strictest of discipline.

According to its charter, which was later copied by the British East India Company, the Dutch Company was the only one authorized to trade with the East Indies, and no one else from Holland was allowed to engage in any such trading for his own personal benefit. In fact, no other Dutch ship was allowed to take the route of the Cape of Good Hope, or Cape Horn, without the permission of the Dutch East India Company. Furthermore, it had the exclusive right to establish colonies, coin money, nominate or eliminate high functionaries of government, sign treaties with other nations, and even make war against them. This Hobbesian trading arrangement was so powerful that it had life-and-death control over all of the sea-lanes of the world, and of the colonies the Company looted for their labor and products. Holland was no longer a country with a company, but a company with a country.

In his Histoire du Commerce de toutes les Nations, the 19th-Century German historian Hermann Scherer described the monopolistic so-called free trade of the Dutch Company. In 1602, after expelling the Portuguese by force from the Molucca Islands in Indonesia, the 14 ships of Admiral Warwyk occupied the most important islands, especially Java, and made exclusive contacts with the indigenous tribes, for the complete control of spice production and trade of the entire region; that is, at the exclusion of any other country.

Scherer reported: "They [the Dutch East India Company] made war on nature itself, by letting her grow her goods exclusively where they intended to have complete control, and by destroying crops everywhere else. A company order restricted the growth of nutmeg trees on the island of Banda; another imposed a ban on cloves on the island of Ambon. In all of the other Molucca Islands, trees had to be burnt and slashed, and any new plantation was forbidden under threat of severe punishment. Treaties were agreed upon with the indigenous people, which sometimes had to be imposed by force of arms. The Islands were closed to foreign ships, and contraband was watched day and night. The whole thing was organized in order to maintain a complete monopoly, and to prevent any price fluctuation in Europe." (Scherer, op. cit., p. 259.)

After a few years of success that had surpassed all of its anticipations, the Dutch East India Company was transformed into a new colonial and political empire. The Dutch Company even made war against British colonial interests in Jakarta. The British knew precisely what the Dutch were up to, and they wanted a piece of the action. In 1618, Adm. Jean Koen fought the British in Jakarta. The city was burnt to the ground and the British were forced out permanently. The city was rebuilt in 1621, under the old Dutch feudal name—Batavia—and became the center of all of the Dutch operations in the Far East. Batavia then became known as the Pearl of the Orient. Such a monopoly expanded into India, into Ceylon in 1658, into Malacca (Malaysia), the Islands of Sonde, the Celebes, Timor, Borneo, Sumatra, and then beyond, into Thailand, Taiwan, China, and Japan.

Since the shareholders of the company were the ones fixing the prices, the "little green men under the floorboards of the stock exchange," in Amsterdam, kept improving the differences between the cost of buying cheap spices and selling them dear, which brought a profit from 200-300% per annum. In his History of Dutch Commerce, historian M. Lueder estimated that during 137 years, from its foundation in 1602 until 1739, the Company had bought for a total of 360 million florins, and sold for a total of 1,620 million florins: a spoiling of nature, and of the general welfare of the people of Holland and of the Far East, in the amount of 1.26 billion florins.

[5] Pierre Clement, Lettres, instructions, memoires, de Colbert, Tome IV (Paris: Imprimerie Imperiale, 1867), p. 216.

[6] Clement, op. cit., p. 235.

[7] "When Mazarin died," wrote historian Pierre Clement, "leaving France in a state of peace on the outside, freed from the factions on the inside, but tired out, without resources, and scandalously exploited by any man who had 100,000 ecus to lend to the treasury at 50% interests; Colbert, who, for a long time, was following with diligence the progress of corruption, who knew all of its ruses and weaknesses, and who was revealing them to Louis XIV; Colbert whom the King consulted first in secret, because the need he had of him was so great; necessarily had to be brought into the Council and occupy the first place. His special skills, his antecedents, his character, his hard work, the important fortune of Mazarin that he administered so wisely during 15 years, but most of all the modesty of the functions he had held under the Cardinal, everything pointed him toward Louis XIV." (Pierre Clement, op. cit., p. 94.

In his article, "Colbert's Bequest to the Founding Fathers," EIR, Jan. 3, 1992, historian Anton Chaitkin appropriately likened Colbert's 1661 bold intervention to a real coup d'état.

[8] See G.W. Leibniz, The Discoveries of Principle of the Calculus in Acta Eruditorum, eight unpublished translations by Pierre Beaudry.

[9] Philip Valenti, "Britain Sabotaged the Steam Engine of Leibniz and Papin," EIR, Feb. 16, 1996; see also Fusion, December 1979.

[10] Pierre Clement, Lettres, Instructions et Memoires de Colbert, p. 305.

[11] Sebastien Le Prestre, Marquis de Vauban (1633-1707), was a Marshal of France and a military engineer who had studied Leonardo da Vinci and especially the great works of Pierre-Paul Riquet. A member of the Academie des Sciences, Vauban distinguished himself by establishing the most advanced form of modern fortification, and surrounding France with a defensive shield by rebuilding more than 300 fortified cities, and creating 37 new ones. (Fort McHenry, located in Baltimore, Maryland, is a typical Vauban fortification.)

Vauban was a Colbertian economist who was preoccupied mostly with improving the conditions of labor, and who considered that "work is the principle of all wealth." Louis XIV unjustly disgraced him, but it was in honor of Vauban that Saint-Simon created the French word patriote.

[12] Roy and Alma More, Thomas Jefferson's Journey to the South of France (New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1999), p. 157.

|

enshrined the benefit or “Advantage of the other”—the common good—in the statecraft of sovereign nations. Two men— France’s Cardinal Jules Mazarin and Minister Jean- Baptiste Colbert (right)—were most responsible for this opening of the principles of nation-building.

enshrined the benefit or “Advantage of the other”—the common good—in the statecraft of sovereign nations. Two men— France’s Cardinal Jules Mazarin and Minister Jean- Baptiste Colbert (right)—were most responsible for this opening of the principles of nation-building.