The Purloined Life Of Edgar Allan Poe:

|

|

| Edgar Allan Poe |

| This article is reprinted from the Spring/Summer 2006 issue of FIDELIO Magazine.

For related articles, scroll down or click here. |

Fidelio, Vol. XV, No, 1 -2. Spring/Summer 2006 |

The Purloined Life of Edgar Allan Poe

by Jeffrey Steinberg

| This account is based on a lecture delivered in Detroit, Michigan in mid-September 2003, to a group of LaRouche Youth Movement members who have launched a research project to revive the life and works of Edgar Allan Poe, and was first published in Executive Intelligence Review, Dec. 12, 2003 (Vol. 30, No. 48). |

A great deal of what people think they know about Edgar Allan Poe, is wrong. Furthermore, there is not that much known about him—other than that people have read at least one of his short stories, or poems; and it’s common even today, that in English literature classes in high school—maybe upper levels of elementary school—you’re told about Poe. And if you ever got to the point of being told something about Poe as an actual personality, you have probably heard some summary distillation of the slanders about him: He died as a drunk; he was crazy; he was one of these people who demonstrate that genius and creativity always have a dark side, and the dark side is that most really creative geniuses are insane, and usually something bad comes of them, because the very thing that gives them the talent to be creative is what ultimately destroys them.

And this lie is the flip-side of the argument that most people don’t have the “innate talent” to be able to think; most people are supposed to accept the fact that their lives are going to be routine, drab, and ultimately insignificant in the long wave of things; and when there are people who are creative, we always think of their creativity as occurring in an attic or a basement, or in long walks alone in the woods; that creativity is not a social process, but something that happens in the minds of these randomly-born madmen or madwomen.

Especially in the fields of literature and music, it’s almost as if there’s a warning out there that bad things happen if you try to be creative. And if you try to really excel at being creative, really terrible things are going to happen to you. Poe is one of those people whose life they falsify, in order to make that false point.

Our Mission as Truth-Seekers

Now, since our job, as a political movement is that of being the truth-seekers—and in that sense, the moral conscience of America and the world—it’s not just an issue of abstract interest that we ought to get to the bottom of the case of Edgar Allan Poe.

In our case in particular, there are some very important parts of the Poe legacy that urgently need to be revived today. On an even more personal level, the last time that we published anything really substantive about Edgar Allan Poe—apart from some papers and presentations that Lyndon LaRouche has given in which he’s made reference to Poe and to some of his writings—was in June of 1981, in the issue of The Campaigner which was appropriately headlined “Edgar Allan Poe: The Lost Soul of America.”*

The author of this article, Allen Salisbury, died a number of years ago, in his early forties, of cancer; and basically, the work on Poe has really been set aside since then, and remains unfinished. So there’s a sense that the LaRouche movement has a kind of debt of gratitude to Allen that needs to be filled, by completing the work on Poe. And as I get into the discussion about what I’ve done so far to get the ball rolling, you’ll get an idea, I think, of why this is something extremely timely right now.

What I really want to talk about, then, is a very preliminary work-in-progress, that hopefully will inspire a number of people in this room to join with me in really pursuing this puzzle; and, in effect, in “cracking the case” of Edgar Allan Poe.

There’s one very good source of information about Poe, which necessarily has to be the starting-point for where we go. That starting-point is Poe’s own mind, as he himself presents it, in a number of writings that were published during his lifetime, and at a time when he was in a position to review the galleys before they went to press. In some cases, the articles and poems that he wrote were published in magazines that he himself edited. The reason that’s important, is that when Poe died—as you can see, at a very young age, 40 years old; and there’s ample evidence that he was assassinated—what happened immediately is that his aunt, who was also his mother-in-law, and who lived with him for most of his adult life, was in desperate straits of poverty when Poe died. One of Poe’s leading enemies, a man named Griswold, went to her and offered her what, by her standards, was a pretty big sum of money, to turn over all of Poe’s personal effects: all of his letters; all of the original manuscripts of his writings; and all sorts of other things, because Griswold said that he wanted to come out in print with a definitive biography, and that this would be part of the collected works of Edgar Allan Poe. And, in fact, a few years later, he did come out with a biography that was a complete and total slander.

Many years later, people came forward and admitted that they knew that a number of letters that were attributed to Poe, had actually been written and forged by Griswold, to convey the idea that Poe was an alcoholic; that he was a drug addict; that he was, basically, a pathetic, psychotic figure at the end of his life.

And so, therefore, even Poe’s own letters, which were first published under Griswold’s supervision, are not reliable. So, as I say, the starting point with Poe, has to be to look at his own mind, and to make certain judgments on the basis of that; and then, it gives you at least a framework for saying what’s true about the fragments of his life which are available, and what necessarily has to be wrong, because it completely contradicts what we know about him by knowing how his mind worked.

Thorough Is Not Necessarily Correct

There is one particular work that I’m going to rely on for the purpose of exploring Poe’s mind; but, what I really want people to do is jump in; you could pick virtually anything by Poe and read it, and come away with the same sense of how his mind works. I think it’s a very good idea, particularly for anybody who is going to join me in working on this project, to do exactly that.*

I want to talk briefly about one of Poe’s short stories, “The Purloined Letter.” I’m not going to read it aloud—it’s quite short—but I’m going to give you the gist of it, and then zero in on a few things that will give you an idea of how the guy’s mind worked.

Poe invented this character named “C. August Dupin,” who is a French private investigator. A number of stories by Poe center around this character Dupin—“The Murders in the Rue Morgue” and “The Purloined Letter” are probably the most famous. In this story, you’ve got, basically, three characters on stage. You’ve got the narrator, who’s a friend of Dupin. You’ve got Dupin. And you’ve got the Prefect of the Paris police—the chief of police in Paris. The narrator and Dupin are sitting around late at night at Dupin’s apartment in Paris, and there’s a knock at the door, and the Prefect of police comes in.

The Prefect says, basically, “Dupin, we need your help. We have a case that’s really simple, but it’s got us completely stumped.”

The story is, that there is a Minister of the French government who has stolen a very incriminating letter, that represents blackmail against another figure in the government. So the police have been asked to get the letter back, and to end this terrible political crisis. The police know, definitely, that this particular Minister stole the letter, because there were eyewitnesses to the fact, who were too embarrassed to say anything. They also know that the Minister keeps the letter very close and easily accessible, because the blackmail may have to be sprung at a moment’s notice. Therefore, he can’t have hidden it away in some hard-to-get-to place—he hasn’t buried it underneath a tree, or out at a country estate, or something like that. It’s in his own apartment.

The Minister is away from his apartment very, very frequently, to the point that the police have been able to go into his apartment dozens of times, and they’ve carried out thorough searches. They’ve looked in all of the obvious places that someone would hide something like this. They’ve used microscopes to check for hidden planks in the floor. They’ve gone into every nook and cranny in the apartment; they’ve checked every table and chair leg. They’ve looked for false bottoms in desk drawers and things like that. And they’ve come up with zero, empty-handed.

Now, unfortunately, they have no choice but to go, embarrassingly, to inspector Dupin, to ask for his help. And what happens is absolutely amazing. Dupin says, in paraphrase, “Well, if you want my help, there will have to be a substantial reward. This is a big deal, a government scandal; there’s a lot at stake here.” The Prefect says, “Well, I’m sure we could oblige you with some kind of financial remuneration.” And Dupin says, “I want 50,000 French francs. Will you promise me right now, that you will give me 50,000 French francs if I can produce the letter?” The chief of police hems and haws, and eventually says, “Yes, it’s a deal.” The chief leaves, and returns several days later to Dupin’s flat. Upon the Prefect’s arrival, Dupin opens up a desk drawer, takes out an envelope, and hands it to him; it’s the letter. It’s the document that the police have been desperate to find.

The chief is so shocked, and at the same time so relieved that the case is now solved, that he immediately writes out a check for the 50,000 francs and goes running out. And the narrator—the third person on the scene—is sitting there completely dumbfounded. And he asks, “What just happened?” So Dupin explains to him: “Well, I happened to know something about this Minister. He’s a mathematician and a poet.”

Algebra and Poetry

Dupin says that, if the Minister were only a mathematician, the police would have solved this case on their own. A mathematician thinks in formal, logical terms, and operates off a set of underlying axiomatic assumptions, that may work in the narrow domain of formal mathematics, but do not work in other areas, such as morals. The formal axiomatic assumptions of mathematics don’t work in morality.

But Dupin knows that this guy’s also a poet. And so his mind works in a way that’s not confined by those kinds of underlying formal, fixed axiomatic assumptions. And he goes on at some length, explaining: I know how these police operate. They’re very thorough; and if they were up against the mind of a mathematician, thoroughness would have caught him every time, because a mathematician is totally predictable. But a poet, on the other hand, has a concept of metaphor, and irony, and therefore is able to think in a way that’s not defined by the same strict set of underlying axiomatic assumptions. Therefore, I have to think about how to catch someone whom I know is both a mathematician and a poet. And I knew that it had to be the case, that he needed to have the letter in easy access to where he was; so I knew it was in the apartment.

But I also knew that he hadn’t hidden it in one of these super-secret places that the police would find. In fact, I surmised that he was playing with the police all along. Because, by being out of his apartment at great length, throughout many, many days, he knew that the police were going to break into his apartment, and were going to search it thoroughly, in the predictable ways that the police, using thse kinds of mathematical underlying axiomatic assumptions, would do the search.

Dupin says, I knew that; and therefore, I knew that the letter had to be hidden in some place that was in such plain sight, and was so obvious, that the police would never think to look there, because they couldn’t imagine somebody would “play us like that”; that somebody would hide something in plain view.

So he says: What I did, was I came up with a very good pretext to go visit the Minister. And he immediately invited me in; we got into a long talk about something we were mutually interested in; and all the while, I was looking around, to figure out where it was. And there, above his desk, was a letter box. And right in the middle of the letter box, there was a letter. And I could surmise by the paper, that this was, possibly, the stolen letter. And I noticed that the letter was badly crumpled up, and dirty, and ripped up around the edges. This wasn’t something that would naturally happen. So I surmised that he probably had done that to make this appear to be something completely irrelevant and inconspicuous. And I managed actually to take notice, that the letter had been folded inside-out; as if you had a piece of paper that you folded one way, and then you reversed it and folded it the other way; and I noticed that the crease was doubled up.

And Dupin saw that there was a seal on it, that was somewhat similar to a Ministerial seal. And so, he simply left. And several days later, he came back for another visit; in the meantime, he had prepared a duplicate piece of paper; and had sealed it, and reversed the fold, and made it dirty in a similar way to the letter that he wanted. And at a certain point in the visit, there were loud shouts and screams outside the window. The Minister went running over to the window to see what was going on. At that moment, Inspector Dupin simply made the switch. The guy looked out the window; it turned out that it was some psychotic who was threatening somebody with a shotgun, and actually fired a shot. And Dupin says that, of course, the shots were blank; this was someone he had actually hired to create the incident, to give him enough time to switch letters.

Dupin even says, that he didn’t want to to merely steal it, because the guy’s livelihood and future career depended on having that letter, and if he happened to notice that Dupin had swiped it, without substituted a replacement, there is no telling what the Minister might have done. He might have tried to kill Dupin. So I wanted to make my escape safely, Dupin explains.

On the other hand, I left something in the substitute piece of paper, so that when he opened it up, he would have some clues, to be able to figure out it was me. But by that time, the game would be up. The original letter would be returned, and everything would be corrected.

Just to read you a couple of paragraphs to make sure that you get an idea that this is really how Poe’s mind is working—I’m not attributing things to him that he doesn’t really say:

Dupin: The Prefect and his cohorts fail so frequently, first, by default of this identification, and secondly, by ill-admeasurement, or rather through non-admeasurement, of the intellect with which they are engaged. [In other words, they don’t try to think about the mind of the criminal that they’re trying to catch.-N-JS] They consider only their own ideas of ingenuity; and, in searching for any thing hidden, advert only to the mode in which they would have hidden it. They are right in this much—that their own ingenuity is a faithful representation of that of the mass; but when the cunning of the individual felon is diverse in character from their own, the felon foils them, of course. This always happens when it is above their own, and very usually when it is below. They have no variation of principle in their investigations; at best, when urged by some unusual emergency—by some extraordinary reward—they extend or exaggerate their old modes of practice, without touching their principles. What, for example, in this case of D—, has been done to vary the principle of action? What is all this boring, and probing, and sounding, and scrutinizing with the microscope, and dividing the surface of the building into registered square inches—what is it all, but an exaggeration of the application of the one principle or set of principles of search, which are based upon the one set of notions regarding human ingenuity, to which the Prefect, in the long repeat of his duty, has been accustomed? Do you not see he has taken it for granted that all men proceed to conceal a letter, not exactly in a gimlet-hole or in a chair-leg, but, at least, in some out-of-the-way hole or corner suggested by the same tenor of thought which would urge a man to secrete a letter in a gimlet-hole bored in a chair-leg? And do you not see also, that such recherchés nooks for concealment are adapted only for ordinary occasions, and would be adopted only by ordinary intellects; for, in all cases of concealment, a disposal of the article concealed—a disposal of it in this recherché manner,—is, in the very first instance, presumable and presumed; and thus its discovery depends, not at all upon the acumen, but altogether upon the mere care, patience, and determination of the seekers. ...So he goes on for a while. You get the idea: There are underlying, axiomatic, formal-logical assumptions that the police make, that work if you are dealing with another mind that’s similarly engaged in formal logic, and has no real creativity. Then he goes on to the question of algebra and poetry.

Dupin: I dispute the availability, and thus the value, of that reason which is cultivated in any especial form other than the abstractly logical. [In other words, the process of human cognition is what counts.-N-JS] I dispute in particular, the reason educed by mathematical study. The mathematics are the science of form and quantity; mathematical reasoning is merely logic applied to observation upon form and quantity. The great error lies in supposing that even the truths of what is called pure algebra are abstract or general truths. And this error is so egregious that I am confounded at the universality with which it has been received. Mathematical axioms are not axioms of general truth. What is true of relation—of form and quantity—is often grossly false in regard to morals, for example. In this latter science it is very usually un-true that the aggregated parts are equal to the whole. In chemistry also the axiom fails. In the consideration of motive it fails; for two motives, each of a given value, have not, necessarily, a value when united, equal to the sum of their values apart.And he goes on along these lines. This is a short story, but Poe is getting into a lesson in epistemology, in the method of how you think.

A Platonic Republican Thinker

So, this is really a fun short story which is, I think, exemplary of Poe’s mind. This tells you a number of things that are quite interesting. Number one: Obviously, Dupin is part of an interesting kind of intelligence network that knows what is going on in Paris. Number two: He not only was able to diagnose the mind of the Minister who stole the letter; but it was also a piece of cake to conclude that sooner or later, the prefect of police was going to come knocking on his door—because he knew that the police couldn’t solve this problem.

So, we know something about Poe: The guy knows how to think. He’s an intellectual of the sort that was versed in Plato; that understood all of the key scientific issues of the day; probably was familiar with Gauss; he certainly was familiar with Schiller, because there are reviews that he had written of Thomas Carlisle’s biography of Schiller, that he had made comments on in one of his magazines [See Box].

But the problem is, that even just by reading this one story—and I can tell you, you can pick at random anything by Poe, that’s certifiably something that he wrote, whether it’s a poem, or a book review, or an essay, or a short story—and you’ll come away with this same sense of the guy’s life. He didn’t have “good days and bad days” in terms of his writing. He didn’t have profound second thoughts. He was a thorough-going, studied, educated Platonic republican thinker.

Knowing that, you’ve got to start from the presumption that most of what’s official about Poe’s life—all of the biographies, which all followed off Griswold’s—were complete fabrications.

Poe died under very mysterious circumstances in 1849, at the age of 40. In 1885—that’s 36 years after his death—the doctor who attended him on his deathbed wrote a book, called Edgar Allan Poe: Life, Character, and the Dying Declarations of the Poet. An official account of his death by his attending physician, John J. Moran, M.D. [See Box]. In this book, Moran says, basically, everything that’s been said about Poe’s death is a lie. Every single thing. And he says, furthermore, I’ve been in contact with members of his family and others; and most everything about his life, at least the conclusions that are drawn in a lot of the descriptions of his life, are also false.

So let’s just start from the presumption that we’re going to investigate Poe’s life, using the exact same method that Dupin used in “The Purloined Letter.” I’ll tell you what I’ve done so far—because the problem that comes up, is: How do you deal with someone who, you at least hypothesize, was part of the American republican intellectual circles that were involved in the struggle both to defend the American republic during a period of great danger to its survival, and who was also committed to the idea of spreading these republican ideas around the world?

Now, there are a few important clues, in certain aspects of Poe’s life, that are so well documented that you can’t really deny them. Like the fact that he was born; and that he had parents; that there were known addresses where he lived; that he had jobs, and people knew him. So there are some things that are known. Then, you get into really murky areas, where there are some things that are said to have happened, according to accounts of people; but which, others say, are completely untrue. How do we start to put together a clearer picture? How do we develop a notion of what’s true, from what’s false about Poe, starting with the fact that the only thing we’re really certain about, is we know how his mind worked; and therefore, we know him pretty well?

The Poe Family and Lafayette

Poe was born in 1809. His parents were actors who travelled around the United States doing performances—everything from Shakespeare to Greek Classics, to less serious contemporary plays. Both his parents died within a few months of one another, in 1811, when he was two years old. He had a younger sister and an older brother, and the three children were split up. The brother went to live with grandparents; the younger sister was adopted by a wealthy family in Richmond; and Poe was also adopted by a wealthy merchant in Richmond, a man named Allan.

Now, what’s interesting is that Poe’s grandfather, David Poe, was a rather important figure in the American Revolution. He was the deputy assistant quartermaster general of the Continental Army, and was assigned to the area around Baltimore, Maryland. He’d been a lawyer there, and the grandfather had actually contributed a fairly sizable amount of his own money to outfit local branches of the Continental Army. And, in fact, the commander of the Continental Army in that area at the time, was the Marquis de Lafayette, who was a leading member of Benjamin Franklin’s international youth movement.

Lafayette was born in 1757, and he lived until 1834. Now, in 1776, when he’s 19 years old, he decides that he’s going to leave France and to come to North America, and he’s going to ask for a commission in the Continental Army. As a young man, he’s been put through military training in France, and through sort of an elaborate process, he actually manages to leave France. The government was not exactly favorable to the idea of young princes coming over and fighting in North America, but he manages to get over here. And, at the ripe old age of—just before his twentieth birthday—he’s commissioned as a Major General in the Continental Army. So, you really do get the idea that we’re talking here about a youth movement, that was instrumental in fighting the Revolution.

So, Lafayette has a particular debt of gratitude to Edgar Allan Poe’s grandfather, because the grandfather puts up his own money to equip the Continental Army units that are commanded by Lafayette. And, in fact, the grandmother spends all of her time, basically, sewing uniforms for the Continental Army. She personally sews 500 uniforms for part of Lafayette’s military unit.

The grandfather died fairly young, and I don’t think there’s any evidence that Poe particularly knew the grandfather, although the grandmother outlived Poe, and therefore, he knew this family history extremely well.

So, Poe is adopted by this fairly wealthy merchant family in Richmond. He goes over to England, studies at private schools, while his foster father is over in England for about 5-6 years on business. And he’s a very smart kid, particularly skilled in language and in geometry, and has a grasp of ancient Greek, Latin, French. He comes back to Richmond, finishes his education.

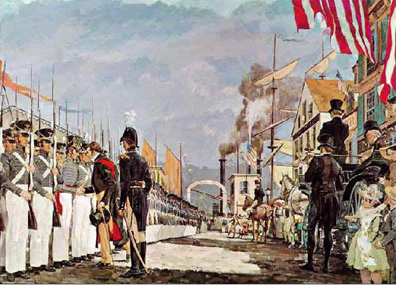

Even before he goes off to college—and, you know, at that time, you could go to college at a pretty young age, he started in 1826, so that was not that unusual—in 1824, Lafayette, at the invitation of the U.S. Congress, comes back to the United States from France. He is by now fairly old, but is really one of the heroes of the American Revolution; and was one of the people in France who broke with the monarchy, but also fought against the Jacobin Terror, the super-radical anti-intellectual mob phenomenon. And in 1824, he came back to the United States. It happened to be a Presidential election year, and he did a tour of all 24 states of the United States, campaigning for John Quincy Adams for President. And, in fact, Adams was elected President of the United States. It actually was thrown into the Congress, and the House of Representatives, by one vote, chose him as President.

And so, during that 1824 trip, Lafayette stopped off in Baltimore, and went to try to find his old friend Gen. David Poe. And when he found out that Poe had died, he went to the grave, and then also visited Poe’s widow, and spent a good deal of time there. A few months later, when Lafayette arrived in Richmond, General Poe’s grandson, Edgar Allan Poe, is heading up the Richmond student cadet corps, and is the person who actually is the greeter, and is heading up the honor guard for Lafayette, while he’s in Richmond.

|

|

During 1824, Lafayette (above) toured all 24 states in support of John Quincy Adams’ Presidential campaign. Left: Lafayette inspects N.Y. National Guard |

Now, all of the official biographies of Poe just sort of make mention of this, but never make any link to the fact that maybe Lafayette went down there looking for him, that he knew General Poe’s—his close friend’s—grandson was in Richmond. They leave this completely out of the history. So, let’s put a question mark next to that, but it’s one of these things where, if you really don’t believe in coincidence, it’s a building block for an investigation that we’re now just barely embarking on.

Now, without getting into all of the psychobabble explanations of his conflicted relationship with his foster father, Poe spends a year at the University of Virginia. In fact, it’s one of the very first classes to begin studying at the University of Virginia. The University was founded by then former President Thomas Jefferson, and, in fact, Jefferson was president of the University at the time. And there were a series of meetings between president of the university Jefferson and the leading students, including Edgar Allan Poe. Again, just make a note of it; it’s another factoid that you might read on the bottom of the screen on CNN, or something, but it’s just sort of floating out there, without any particular significance.

The Military of the Republic

After a year at the Unviersity of Virginia, Poe enlists in the Army, and spends the next three years as an enlisted man in the Army, and he winds up at Fort Monroe, in Virginia. In 1829, he decides that he wants to get out of the Army, and back then, if you could purchase the services of somebody to replace you in the Army, then you would be given an honorable discharge. Which is what happened.

Poe left the Army, because he was going to enroll in West Point, the U.S. Military Academy, that had been founded in 1802 on the model of the French École Polytechnique. This was the most advanced engineering and science academy in the United States at the time, and many other engineering schools, both military and civilian, were created as deployments out of West Point over the next 20-30 years: Rensselaer Polytechnic in New York, the Virginia Military Institute, all of these schools were created by West Point graduates, who basically were extending this network of polytechnique academies. They had the best scientific education, the best libraries, the best engineering training, of any universities in the United States at the time.

|

|

|

The U.S Military Academy at West Point, modelled on the French Ecole Polytechnique, was a center of scientific education in the young rebublic. Above: West Point and Sylvanus Thayer (left), its first Commandant. Below: The Ecole Polytechnique. Among its founders was the scientist-statesman Lazare Carnot (right), who organized the defense of Revolutionary France by recruiting and training brigades of youth as military engineers. |

|

The commander of the fortress where Poe had been serving in the Army sent one of the letters of recommendation to get Poe into West Point; and one of the people who also helped to sponsor Poe’s appointment was Gen. Winfield Scott, who was a major figure within American republican military circles. He’d run for President—a very important figure.

All right. So, Poe stays at West Point for only a year. He enters in June of 1830, and he leaves in February of 1831. He’s ostensibly kicked out, for disciplinary reasons. But he was number three in his class in language; number 17 in his class in science. He was a top, top student, and obviously somebody who had the educational background that is reflected in just the short excerpts that I read from the “Purloined Letter.” While he’s a student at West Point, he’s already writing some of his most famous poems, and short stories, and letters.

What happens to Poe after he leaves West Point, is one of the most interesting and highly disputed aspects of his entire life. One thing that’s acknowledged, is that after he’s been “kicked out” of West Point, he goes to the Commandant of West Point, Col. Sylvanus Thayer, and asks him to write a letter of recommendation, so that he can go to Poland and be given an officer’s commission in the Polish Army, which is waging a republican revolt against control by Russia. And so, he wants to be given this letter of introduction. And, indeed, Thayer provides the letter.

Now, it’s claimed by Griswold that there’s no evidence that Poe ever left the United States, that he never travelled overseas. But, there’s an interesting letter that was written by a famous French writer, named Alexandre Dumas, to a contact in Italy in 1832. Anybody ever hear of Dumas? He wrote The Three Musketeers, quite a number of famous novels. And you can see up there, his years, 1802-1870. He lived a lot longer than Poe, but was only seven years older.

So, this is Dumas’s letter, to an Italian police official. He said: “It was about the year 1832. One day, an American presented himself at my house, with an introduction from ... James Fenimore Cooper. Needless to say, I welcomed him with open arms. His name was Edgar Poe. From the outset, I realized that I had to deal with a remarkable man. Two or three remarks which he made upon my furniture, the things I had about me, the way my articles of everyday use were strewn about the room, and on my moral and intellectual characteristics, impressed me with their accuracy, and truth.”

Poe, Dumas, and Cooper

So, here you’ve got Dumas, writing a letter saying, Hey, this guy Poe showed up at my doorstep, with a letter of introduction from James Fenimore Cooper, and he lived with me for several months. Dumas actually describes how Poe loved to roam around the city at night; how he was given a guest room at Dumas’s house, and during the day, he would have the curtains down, and would make the room as dark as possible, and would try to sleep during the day; and then, when he read, he only read by candlelight; but that, as soon as the sun went down, he’d grab Dumas, and they’d go walking all over Paris, and they’d be talking.

Now, the “official” argument is, that, well, number one, it’s obvious that Poe never was in Paris, because the street names he uses in his stories don’t exist in Paris. If he was really in Paris, he’d know the right street names. And they just sort of slough over this whole story, and say, well, we’ve got letters from this person, and that person—who were all part of this enemy operation after his death, to discredit him—that claim to be involved in various intrigues with him in Baltimore during this period from about 1831 through 1833.

The preponderance of evidence, as we will see, is that Poe, indeed, was in Paris during the period referenced by Dumas—despite the efforts of Griswold and company to cover up this crucial event in his life. Now, let’s explore what the implications are, of Poe, James Fenimore Cooper, and Alexandre Dumas.

Well, one thing that’s interesting, is: Go back to the Marquis de Lafayette, who was part of the Franklin youth movement. Now we’re getting towards the later years of his life. He’s made this trip to the United States in 1824. He’s gone back to France, and in 1830, he’s led a briefly successful republican revolution in France. They’ve installed someone on the throne, who’s agreed to establish a full constitution under the monarchy, and the Marquis de Lafayette is made the commander of the French National Guard, the equivalent of being the general-in-charge of the entire army. And Alexandre Dumas is one of his officers. So, there’s a political association within American System, republican circles in France, which establishes Dumas as somebody at least worth looking into further, as probably one of Lafayette’s protégés in these “American” republican networks, over there in France.

Now, a few other interesting things come up, including well, okay, what’s this business with James Fenimore Cooper? Where does he fit into the picture? Ever heard of Cooper? [Audience: He wrote The Last of the Mohicans and The Spy.]

You’ve already jumped one level above what most people know by even mentioning his book The Spy, which was a very excellent book about the American Revolution. Most people, frankly, know him from things like The Last of the Mohicans and The Deerslayer, a whole bunch of these wilderness adventure novels. Well, let me tell you a little bit more about James Fenimore Cooper.

His father, William Cooper, was a three-term member of Congress, a leading figure in the Federalist Party, a fairly wealthy developer—basically, a city builder. If people have heard of Cooperstown, New York, it wasn’t named Cooperstown because Cooper was born there; it was named Cooperstown because Cooper’s father founded it. Cooperstown is north of Albany, New York, and at the time, this was a really barren area.

So, it’s out there. It was quite a substantial adventure to go there, and actually found a city, and actually build it up as a serious city. It’s right on the Hudson River, upstate from New York City.

So Cooper was basically steeped in this republican tradition. He becomes a pretty famous republican political activist, and writer. In 1824, when Lafayette comes to the United States, he meets Cooper in New York City, and they establish such a close relationship, that Lafayette asks Cooper to write an account of his tour of the United States, which Cooper did write, as a historical novel called Notions of the Americas. So Cooper is actually extremely close to Lafayette. He’s practically travelling as Lafayette’s personal secretary, during this period of Lafayette’s 18-month tour of the United States, and he writes the definitive account. And in that book, he quotes Lafayette as saying, “America’s greatest institution is its future.” Which is a pretty appropriate and insightful comment about what the spirit of the United States was, during this period, with the republican ideas still very much alive.

John Quincy Adams is President of the United States. And this is the period in which the United States is most reflecting this concept that Lyndon LaRouche talks about all the time; namely, this notion about the community of principles among perfectly sovereign nation-states.

Washington Irving and Samuel Morse

What do you know about Washington Irving? [Audience: “Sleepy Hollow,” “Rip Van Winkle.”]

So, again, he’s not unfamiliar. He’s not only famous, but his legend lives on. But, did you happen to know that he was the U.S. Ambassador to Spain? He was the most famous biographer of George Washington. He was in Spain twice: in the 1820’s and 1830’s, and then he was in Spain again in 1842-1845. And during his first tour of duty, at the embassy in Spain, from 1829 to 1832, he did voluminous writing—a three-volume biography of Christopher Columbus, for instance. And his study of Islamic culture, which you can find in writings like The Alhambra and his biography of the Prophet Mohammed, was based on the fact that he understood the paradox of Spain around the time of Columbus: This was the period of both the exploration, but also the period of the Inquisition, where the Jews and Muslims were expelled from Spain. And so, he realized that prior to the expulsion of the Jews and Muslims from Spain, Spain had a higher level of culture, than afterward.

Benjamin Franklin had a pretty good understanding of Islam as well. In a letter he wrote about the Indian massacres in Lancaster county, he speaks a lot about the question of hospitality, and the humanist current in Islam. And even gives stories from Islamic Spain, and different things, and also from the Koran.

Spain had what was referred to as the Andalusian Renaissance, which preceded the later Italian and European Renaissance, and was a reflection of the Islamic Renaissance that had been a major center of civilization during the Tenth and Eleventh centuries, the period of Ibn Sina. And so, this effort to revive that notion of Islam, as a kind of dialogue of civilizations, is something that was a very conscious factor within all of these American networks, particularly those operating in Europe. And again, Washington Irving’s deployment into Spain during this period of Hapsburg domination in Spain, also has the earmarks of an intelligence deployment.

So, Washington Irving is also in Europe, in this fateful period of 1831-1832, when Poe was in Paris.

One of the other members of the “literary” Bread-and-Cheese club of our friend Cooper, back in New York City, before he goes off to Europe, is a guy named Samuel Finley Breeze Morse. Anybody ever heard of him? [Audience: Morse Code?] Exactly. The guy who invented the telegraph, and then developed the Morse Code. Anybody know anything else about him?

Well, he was America’s leading second-generation painter. In fact, the biography that I have of Morse, is called American Leonardo, and he actually is an extraordinary portrait painter. Now, Morse comes from an old Revolutionary family. Morse’s father, Jedidiah Morse, is the first American geographer. He writes the first geography book about North America. It’s a fairly good hypothesis that he has some knowledge of, if not some kind of direct collaboration with, Alexander von Humboldt.

But you notice, I’m talking a lot about developments in Paris. I know that there are major German connections as well, into the German reform movement, the Republican circles typified by Humboldt, and then somewhat slightly later, by Friedrich List. This is a whole other area of investigation that I haven’t even had time to touch on yet, but I know that it’s a very fertile field, because Franklin had extensive networks in Germany, at Göttingen University, the whole circle around Abraham Kästner, who were doing the translation of Leibniz from an earlier period. So, this is a whole other area that we’re not even going to get into tonight, but I just want to put on the table, as another dimension of this investigation.

So, Morse’s dates are 1791-1873. He’s one of the few people on our list of Poe collaborators who lived a fairly long life. He’s also one of the few people who actually wound up being relatively wealthy in his old age, largely because of the patents on the telegraph.

But, he’s a guy who’s a painter. He’s an inventor. His father is a leading geographer, as well as being one of the top Puritan theologians in New England, the reverend of the leading church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, which is just across the Charles River from Boston, right next to Cambridge. And there’s a kind of a funny note in one of the short biographies of Morse, that I think sort of gives you a flavor for the guy, somebody who definitely would have joined the LaRouche movement, were he around today, or were we around then: “In his junior year, Morse was expelled from Yale, because of a series of pranks, which included training a donkey to sit in a professor’s chair.” So, you know, here’s a guy who’s got a healthy sense of humor, and a healthy sense of disrespect for pompous academics.

But, so, Morse is trained as a painter. He goes over to England, and over in England, there are a whole group of great American portrait painters. They’re deployed all over Europe. Ostensibly, Europe, with its more traditional culture, is a better place for an artist to earn a living, than America. Obviously, there’s a real desire to study at the seat of the Renaissance, and so Morse spends a lot of time in Rome; but he actually spends a number of years in England, and winds up getting the opportunity to paint the portraits of a lot of leading figures in English public life, in the government, in the House of Lords, in the Royal Family. Now, it’s known that a number of these American painters were over there not only as artists, but as spies. They were the eyes and ears of the American republic in Europe. Because what better way to find out what the intrigues of the European oligarchies are, against the American republic, than by being the sort-of dumb, innocuous American, gifted painter, day after day, being there in the private chambers of government officials, and members of the Royal Family, while people are constantly coming in, and interrupting, for signatures on documents, and private discussions?

|

|

|

|

|

|

So, they were over there doing a lot of intelligence. In other words, there was a period in American history where we had a pretty good republican—“small r” republican—intelligence service. And it was all epistemology. It was all, as Poe discussed in the “Purloined Letter,” knowing the underlying axiomatic assumptions of how the other person thinks, and being able to literally read their mind, by understanding the blocks that they’ve adopted through their mode of thinking.

Now, in 1824, Morse was a member of Cooper’s Bread-and-Cheese club in New York City, with Washington Irving as the honorary chairman—and there’s dozens of other people who are involved in this network, I’m just highlighting three or four of them, for reasons that are going to be even more obvious. And when Lafayette comes to New York, in 1824, Morse enters the competition to be hired by the City of New York, to do an official portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette, to commemorate his tour of the United States. And, he wins the prize.

So, he’s sent down to Washington, to meet with Lafayette. He does the preliminary work on the portrait, and at some point shortly after that, Morse goes to Europe. And he spends most of his time in Paris, almost constantly in the company of his closest friend, James Fenimore Cooper. He goes practically every day, with Cooper, to the Louvre; and Cooper stares over Morse’s shoulder while he’s doing copies of famous paintings, and doing other things. Cooper and Morse are both members of the American Polish Committee. So, in other words, they’re all involved in republican revolutionary politics, in Paris, during the same period of time. Morse is actually living two blocks away from Lafayette, and is frequently visiting with Lafayette, during this whole period.

Eventually, by about late 1832, the Polish Revolution fails, a lot of the key people escape to France, and Lafayette is their main protector. And there are descriptions—if you do as I did, and take a fairly good biography of Cooper, of Morse, and a whole string of bad biographies of Poe, and look into each of these things, and look for interesting points of intersection. The fascinating thing is that the main point of intersection is the Marquis de Lafayette. And, in a certain sense, in Europe at least, Lafayette became the leading American republican, carrying forward the mission of Benjamin Franklin in Europe.

Even though you have this horrible period, beginning with the Jacobin Terror in France, then Napoleon Bonaparte, then the wars, then the period of the Congress of Vienna, where all of the different oligarchical factions in Europe all got together and said, “We, as a bloc, will crush republicanism in Europe.” During this period, Lafayette is in jail for five years, in the jails of the Habsburgs. Ironically, he gets out of jail when Napoleon defeats the Habsburgs in the military campaigns in Central Europe.

But, the point is that you’ve got this brief period of republican upsurge in the early 1830’s in Europe, and it’s noteworthy that all of these Americans are there for it. And they’re all personal friends in the immediate circles of the Marquis de Lafayette. Others who were over there, by the way, during the same time period, include Gen. Winfield Scott, who, remember, was one of the people who recommended Poe to be commissioned to attend West Point.

The ‘Cincinnati’

Now, there’s another interesting dimension to this transatlantic collaboration between the Lafayette circles in France, republican circles in Germany and other parts of Europe, and the really inner core of the American revolutionaries. And that’s an organization called the Society of the Cincinnati. Anybody ever heard of this?

It’s a controversial, but extremely important organization. Cincinnatus, in Roman history, is a famous Roman general who, after he agreed to take command of the Roman armies, is basically told that if he succeeds in his military conquest, he’ll be made the dictator of Rome. And he succeeds in the military conquest, becomes dictator of Rome, and after a very, very, very brief period of weeks, maybe months, retires from that position, and goes back home and resumes his life as a farmer. So, Cincinnatus is the symbol of the citizen-soldier, who is not out to make a permanent career in the army, but who considers himself a citizen of the republic, a productive member of society, who will serve his country, but without any aspiration of becoming a dictator, or some other kind of imperial Roman figure. He rejected the powers of Caesardom, and went back to the simple life of a farmer.

Now, the American Revolution was a pretty rough affair, and the people who suffered some of the greatest hardships were the leading people in the military. And even when the British formally surrendered at Yorktown in 1781, ostensibly ending the American Revolution, the British still maintained fairly substantial troops inside the United States. New York City was a British-occupied city; Detroit; a number of other places. So, the Continental Army had to be maintained until the British were finally fully driven out of the United States. The Treaty of Paris negotiations were going on in 1782-1783, but the situation on the ground here in North America still wasn’t secured. So, had the Army decommissioned, and had everyone simply gone home, things could have very easily fallen apart, and the British could have actually overturned the American Revolution.

So, these were very difficult times, and the military was being underpaid. There were all sorts of conflicts in the Congress. The Articles of Confederation, which were the governing constitution at the time, were very loose. There was no centralized national bank, there was no national currency. The states dominated, and so it was a pretty dangerous situation. And George Washington and the other leaders of the military were aware that there were some hotheads inside the military—maybe they were British agents, maybe they were just people who were really frustrated with how things were going, frustrated that the Congress was not adequately providing funds to keep the military functioning—and at one point, there was actually a document circulating called the Newburgh Address, by a group of senior officers, who were proposing a military coup. Overthrow the Congress, overthrow the Articles of Confederation, and set up a military dictatorship.

|

Washington’s Cincinnatus Society was nameD for the Roman citzen-general. Below: Cincinnatus statue, Cincinnait, Ohio. Left: George Washington, who reputiated the military coup plan, Newburgh, May 1782. |

|

Washington and others had to move very forcefully against it, but they also had to address the fact that there were legitimate grievances. And so, they decided that, rather than operating through intrigue, they would set up an organization representing the officers who had served in the American Revolution. And they chose the name Cincinnatus for the organization. In May of 1783, they founded the Society of the Cincinnati, and made it an organization of the veterans of the American Revolution. And they had criteria for membership and all sorts of things, and basically their concern was not just with military issues, but to make sure that the American Revolution survived, beyond the first generation.

This was a big issue. There’s that famous quote from Benjamin Franklin, who came out of one of the last sessions of the Constitutional Convention, when the draft had been pretty much completed, and a woman came up to him and said, “What have you given us?” And Franklin replied, “A republic, if you can keep it.”

So, this question of, how do you create the institutions that assure the survival beyond the first revolutionary generation?—I think someone was commenting earlier today about the fact that, after the death of Franklin, a number of people deteriorated in their moral and intellectual courage. Jefferson had problems. Pretty much all of them did. And yet, there was a clear understanding that an institution had been established that would survive.

So, the Society of the Cincinnati was deeply concerned at the danger of both a British reconquest, or a descent into anarchy. And so, the Cincinnati set up chapters in every state in the union.

One of the initial major campaigns of the Society was to organize for a Constitutional Convention. And in fact, when the Constitutional Convention was convened in Philadelphia in 1787, of the 55 delegates to the Convention, 21 were members of the Society of the Cincinnati. In fact, the annual meeting of the Society was convened in Philadelphia simultaneous to the opening of the Constitutional Convention, and many people were going back and forth between the Cincinnatus meeting, and the Constitutional convention. So, in other words, there was a very large input by the Society of the Cincinnati into the Constitutional Convention.

The Society’s first president was George Washington. Among the leading members of the Society, from its inception, was George Washington’s aide-de-camp, Col. Alexander Hamilton, who, on Washington’s death in 1800, became the second president of the Society of the Cincinnati. One of the other leading founding members, the person who was thought to have been really one of the initiators, was the German who had come over and been an important general—like the chief organizer—of the Continental Army, Baron von Steuben. So, he was one of the very first founding members of the Society of the Cincinnati.

Now, on July 4, 1784, about 13 months after the Society was founded, a second branch of the Society was established in France, and guess who the president of it was. Our friend Lafayette. And the whole purpose of the Society was the spread of republicanism, the securing of the republican revolution in the United States, through the adoption and then the passage of the Constitution; and then the idea to continue to look back at the situation in France, as the obvious next place to organize such a republican revolution.

The Jacobins were well aware of the existence of the Society of the Cincinnati. In fact, the leading right-wing Shelburne agent in France, the Count de Mirabeau, wrote a pamphlet attacking the Society of the Cincinnati; so a lot of the key members in France were well-known. It doesn’t take a brain surgeon to know it, because these were all the French who had gone to the United States and become officers, like Lafayette as a 20-year-old, a major general, in the Continental Army. The Count de Rochambeau was another leading French nobleman who came to the United States, bringing with him 600 French volunteers, who served in the American Continental Army during the Revolution.

A Hologram of Poe

Who were some of the other people who were later brought into the Society of the Cincinnati? Dewitt Clinton, the Governor of New York, who was the person who arranged for James Fenimore Cooper to be appointed as the American consul in Lyons in France, was a member of the Society. After the war of 1812, Gen. Winfield Scott, who was one of Poe’s West Point sponsors, was brought into the Society of the Cincinnati. Again, this is really just sort of threadbare leads.

There were members of the Society from Europe, from France and elsewhere, who went to Russia; and, for example, the Minister of the Navy in Russia, from 1811 to 1819, was a French marquis who had fought in the American Revolution, was a member of the Society of the Cincinnati, and was then placed into this position in the court and in the military under Catherine the Great, who herself, of course, was very important in securing the supplies from Europe for the Continental Army during the Revolution.

So, we’re getting a sort of a picture here. We still haven’t said a whole lot about Edgar Allan Poe, except to take note of the fact that an awful lot of people who were clearly part of this transatlantic republican movement, that was extremely active up through the 1830’s, all appear as important figures in what little we know about Poe’s life.

So, what have we done here? We really have constructed a kind of hologram. We don’t really have the flesh and bones filled in very much, but we started out in a direct dialogue with Poe’s own mind, and came away with something that we can really be absolutely certain about. We know how the guy thinks. We know how he thought as a relatively young man. We know he had the intent of going to Europe, to participate in these transatlantic republican efforts at making revolutions in Poland, and in France, during this period. And, quite frankly, I find it hard to dispute the Dumas account of Poe’s visit to Paris. There’s no reason to assume that all of the official biographies that attempt, hysterically, to dispute this point, are to be believed.

So, we’ve got a notion of certain elements of his life. One of the things that I’m going to do as soon as I get back to Washington, over the next couple of days, is visit the Society of the Cincinnati, which has its headquarters in Washington. The Society really reached its peak in the middle of the Ninetenth century; nevertheless, it still exists, and there’s a beautiful museum and archive, public archive, of all the papers of the Society. And since all I was working off of was one semi-official history, called Liberty Without Anarchy: The History of the Society of the Cincinnati, my hypothesis is that David Poe was a member, since he met all of the membership criteria, and there were people who were made members posthumously. And it was an organization that, at least through the Nineteenth century, was a hereditary organization, meaning that if you were a direct descendant of an initial member of the Society, then you were eligible for membership also.

My hypothesis is that Poe was one of the leading American republican counterintelligence officers, and that he was working for the Cincinnatus Society military intelligence circles. He was sent to Europe in the early 1830’s as part of a transatlantic campaign by the Society to make republican revolutions in France and Poland, and elsewhere, if possible. And his literary career here in the United States was dominated by the kind of intelligence warfare, cultural warfare, that was an absolutely crucial part of the fight for the survival of the United States, and the spread of the American System around the world.

The leading enemy of all the people that we’ve been talking about here—Cooper, Washington Irving, Morse, Poe, all of these writers who were each in their own way, demonstrably, leading republican intelligence officers—was the Scottish writer Sir Walter Scott, who was also in Paris in this 1831-1832 period. And what he was doing there, was putting the finishing touches on what he considered the greatest work of his career, namely the authoritative nine-volume laudatory biography of Napoleon Bonaparte.

There are other people who were part of the Walter Scott circles of British imperialist writers, including Thomas Carlyle, who were also engaged in this kind of warfare, against Poe and the others. There were a number of literary journals, including Blackwoods Journal in England, which promoted the worldview and ideas of the British oligarchy, and the Venetian system, over and against American republicanism. And they sponsored their own networks inside the United States; many of the New England Transcendentalists were part of these British, Scottish Enlightenment, anti-republican, really anti-American circles; but that’s a sort of a large issue to take up at another time.*

What I think is absolutely essential, is that we launch a real project to complete the unfinished work and mission of Allen Salisbury. Because, if the United States is going to survive today, then it’s our mission to reconstitute exactly the kind of republican intelligence operation, on a worldwide scale, that was absolutely vital in consolidating and spreading the ideas of the American Revolution around the world. And if we can, working together as a kind of taskforce, crack the case—the “Purloined Letter” case—of Edgar Allan Poe, then we will have achieved something that will have immediate tremendous benefit in becoming a key tool for organizing the revival of the kind of the intelligence service that won’t fall for “Niger yellowcake” and other stories, like what happened in the lead-up to the Iraq war.

Related Articles |

What is the Schiller Institute?

Edgar Allan Poe: The Lost Soul of America, by Allan Salisbury

Fidelio Table of Contents from 1992-1996

Fidelio Table of Contents from 1997-2001

Fidelio Table of Contents from 2002-present

Beautiful Front Covers of Fidelio Magazine

|

New Evidence of Poe’s Transatlantic Republican Ties

The obfuscation of Poe’s role in the Nineteenth-century’s transatlantic republic networks has also involved an insistence on the part of official biographers, of Poe’s ignorance of the German language, in spite of his many references to German literature and language. This is particularly the case with regard to any affinity Poe might have had for the work of that other great republican playwright and poet, the German Friedrich Schiller. For example, it has only recently been established with some certainty, that Poe was the author of the unsigned review of Thomas Carlyle’s Life of Schiller that appeared in the Broadway Journal on Dec. 6, 1845, while Poe was the editor of that magazine. Six months earlier, on June 28, that same journal published a review of the first English translation of Schiller’s “Letters on the Aesthetical Education of Man.” While is has not yet been proven that Poe was the author of that particular piece, its appearance in his magazine certainly testifies to his high appreciation of Schiller’s works. But, did Poe know Schiller solely through the medium of translation, given the numerous translations of his works which achieved a great deal of popularity in the United States at that time? The discovery in the Poe archive at the University of Texas at Austin, of Poe’s own printed copy of his Eureka, which contains on the first page an autograph transcription in German of Schiller’s poem “Die Grösse der Welt,” ought to dispel the fog that has been spread around this question. Poe’s inscription of Schiller’s poem on the front flyleaf of his own copy of this, his most philosophical work, presents solid proof that Poe was well acquainted with Schiller’s work—and even in its original German! It is also further evidence of the enormous effort undertaken to bury Poe’s involvement in the true history of this period, and of why you cannot take the so-called “facts” proferred in the official biographies at face value. —William Jones |