Rembrandt Portrays Jesus ‘from Life’

by Bonnie James

November 2011

Figure 1 Musée du Louvre

“The Supper at Emmaus,” Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn, 1648.

|

A young man sits at a table with two companions as a waiter hovers nearby with a platter of food, oblivious to the drama that is taking place before him (Figure 1). The man in the center of the picture is breaking the bread—a braided challah, the traditional bread eaten by the Jews on religious holdidays. The man appears not to be thinking about the meal, or his surroundings; instead, he seems to look beyond this world; his expression suggests an inner peace or contentment. There is light that surrounds, and seems to emanate from his head, forming a kind of “halo,” suggesting that he is a holy figure; there is something unmistakably sacred about the scene.

In fact, he is the risen Christ, and the two men are his disciples, with whom he has journeyed to the village of Emmaus.[1] But they do not know him, until he blesses the bread, breaks it, and gives it to them, as described in Luke: Then “their eyes were opened, and they knew him; and he vanished out of their sight.”

Above all, it is the face of Jesus that we are drawn to in this painting, “The Supper at Emmaus.” Rembrandt has placed Jesus within a huge, Roman-style arch, suggesting the architecture of a great church; the light that emanates from his person is a sign of his divinity; a second, brighter light from an unseen source on the left side of the painting illuminates the white cloth on the table, and reflects back onto the figures at the table. The brightest light falls on Jesus’s face and hands, as he breaks the bread—the miraculous moment when his true identity is revealed to his disciples.

Rembrandt’s portrayal of Christ represents a radical break with artistic tradition up to that time. As the superb exhibition, “Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Aug. 3-Oct. 30)[2] establishes, Rembrandt’s use of Jewish models—a young Sephardic Jew in particular—to portray Jesus, was entirely original in the history of art.

It is well known that Rembrandt lived in the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam into which there had been a mass immigration of Spanish and Portuguese Sephardic Jews, who were fleeing persecution by the Inquisition, which continued long after the 1492 Expulsion from Spain; there were also increasing numbers of Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern and Central Europe, escaping persecution there, and the horrors of the Thirty Years War.

After Rembrandt was driven into bankruptcy in 1656,[3] an inventory of his vast collections of artworks, curiosities from around the world, and other precious items, was made. Among them were small three paintings of the head or face of Christ, one of them described as painted “from life.” Of course, Rembrandt did not actually paint Jesus “from life”—but he did the next best thing: He depicted a model from among his Jewish neighbors, whose appearance he believed would have been closest to the living subject.

Leiden and the Religious Wars

Rembrandt paints “The Supper at Emmaus” in 1648, an auspicious year: The prolonged nightmare known as the Thirty Years War ends with the historic Peace of Westphalia; at the same time, the Eighty Years War, which established the independence of the Dutch Republic from Habsburg Spain is concluded, with the Peace of Münster. Rembrandt’s life (1606-1669) has been shaped by both wars in myriad ways.

Leiden, the city of Rembrandt’s birth, less than 30 miles from Amsterdam, was one of the leading intellectual and artistic centers in Europe, home to the celebrated Leiden University. It was also a magnet for refugees from religious persecution from all over Europe—not only Jews, but Catholics and Protestants escaping the devastation of the wars that had overtaken the continent. The worst effects of Thirty Years War (1618-48) were in present-day Germany, where an estimated 5 million people died, one-third of the population.

Leiden was also a center for the movement known as the Brothers of the Common Life, which promoted the idea that the believer should develop a personal relationship to God, without the intercession of priests, or other clerics. By reading the Bible, the individual would develop the spiritual strength to live in “the imitation of Christ.” This revolutionary idea obviously required that the common man be literate. Thus, Rembrandt, even as the ninth of ten children of a miller, like others of his economic status, attended the Latin School in Leiden, from age 9 to 13, where he was educated in mathematics, Greek, Classical literature, geography, and history. At age 14, he entered Leiden University where he undertook studies in science, including anatomy classes. The following year, he was apprenticed to a local artist, Jacob Isaacsz. van Swanenburg, with whom he studied until 1622.

During this period, Leiden began to suffer the effects of the religious warfare that was tearing Europe apart. In 1618, the ecumenical government of Leiden was overthrown, and a virtual Reform dictatorship installed. The coup extended beyond the city council, into the schools, and other institutions of civic life.

Rembrandt’s family was associated with a Protestant sect known as the Remonstrants, who were political opponents of the radical Calvinists. Members of this group, which included Catholics and other Protestants, with ties to Amsterdam, the economic and cultural center of the nation, formed the humanist network which nurtured Rembrandt in his early years in that city.

This background will, to a large extent, determine Rembrandt’s response to the cataclysmic forces that shaped The Netherlands in the 17th Century, including to his neighbors in the Jodenbreestraat, the Jews’ Broad Street.

Portraits of Jesus

As noted by Lloyd De Witt, a curator at the Phildephia Museum of Art, “Not only did Rembrandt abandon traditional sources in his presentation of Jesus mid-career, but as many scholars have persuasively proposed, supported by visual and circumstantial evidence, he used as his model a young Sephardic Jew from the neighborhood in which he lived and worked. This was very likely the first time in the history of Christian art that Jesus appeared to be Jewish.”

A look at some of the earlier portrayals of Jesus makes the point (Figures 2-6).

Figure 2  Wikimedia Commons

Byzantine icon of Christ, detail from a mosaic, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, 13th Century.

|

Figure 3  Wikimedia Commons

The Shroud of Turin (postive and negative images), First Century A.D.

|

Figure 2 is a Byzantine icon from the 13th Century, quite typical of religious images of Jesus for hundreds of years. Notice the stylized, immobile features of the face, the pale skin, long narrow nose, tiny mouth. This image, and others like it, were based on what were believed to be holy relics, such as the Shroud of Turin (Figure 3), which were accepted as miraculous imprints of Christ’s face. As late as 1958, Pope Pius XII approved the Shroud for devotion by Roman Catholics, as the face of Jesus.

Figure 4  “Jesus Driving the Moneychangers from the Temple” (detail), Giotto, Scrovengi Chapel, Padua, 1304-06..

|

There was a dramatic shift at the dawn of the Renaissance. As early as the first decade of the 1300s, the great Florentine artist Giotto (a collaborator of Dante Alighieri) began to set his figures free from the two-dimensional, stylized, fixed-stare mode we saw in the Byzantine icon, and instead, we now see them moving about in space, in a believable, if not yet scientific, perspective. In this detail of a fresco in Padua, “Driving the Moneychangers from the Temple” (Figure 4), Jesus comes alive. And yet, Giotto’s rendition of his face is faithful to tradition.

By the middle of the 15th Century, when the Italian Renaissance was in full flower, the image of Christ in art begins to take on a somewhat different aspect, as can be seen in the detail from a beautiful painting of “The Baptism of Christ,” by Piero della Francesca (1450) (Figure 5). Here, the figures begin to assume a Classical form, reflecting Renaissance humanism’s revival of Classical Greek ideals; they have become fully three-dimensional, unlike the Byzantine icons. Still, Christ’s face is nearly identical to the 13th-Century image (Figure 2).

Figure 5  Wikimedia Commons

“Baptism of Christ” (detail) Piero della Francesca, 1448-50.

|

Figure 6  “Self-Portrait (as Christ),” Albrecht Dürer, 1500.

|

One of the most intriguing and audacious images of Christ is the “Self-Portrait as Christ,” of 1500 (Figure 6) by the German artist Albrecht Dürer (who was greatly admired by Rembrandt). Here again, despite the decidedly secular presentation, the face of Dürer/Christ bears a strong resemblance to the earliest images.

As we can see, this image became the template for thousands of depictions of Jesus, both in the Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches, even into the time of Rembrandt, who would himself rely on this tradition—until 1648.

Rembrandt’s Jesus Is the Metaphor for Westphalia

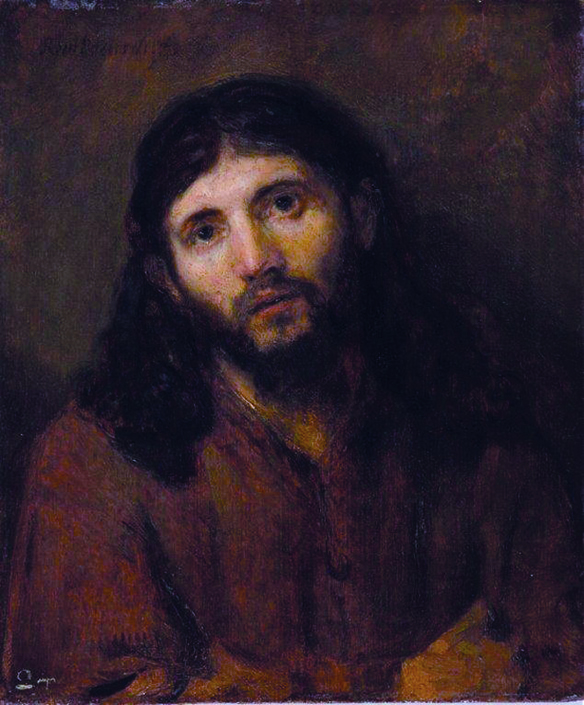

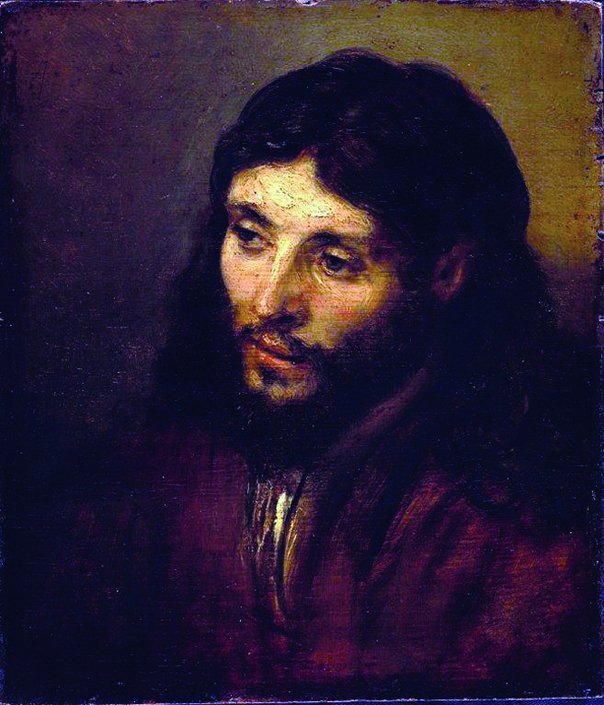

The Paris-Philadelphia-Detroit exhibition pulls together, from six cities in three countries, a series of heads (tronies, the Dutch word for head), small oil paintings on wood, of a single model representing Jesus (see Figures 7-9 for three of them). Three of these were listed in the inventory of Rembrandt’s possessions in the 1656 bankruptcy. That these were meant as “sketches” for more finished works can be demonstrated by the fact that the same face appears over and over in Rembrandt’s portrayals of Jesus in paintings and etchings.

Figure 7  Detroit Institute of Arts

“Head of Christ,” Rembrandt, 1648-54.

|

Figure 8  Philadelphia Museum of Art/John C. Johnson Collection

“Head of Christ,” Rembrandt, 1648-56.

|

Figure 9  Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

“Head of Christ,” Rembrandt, 1648-50.

|

Most prominent among those works are the previously mentioned “Supper at Emmaus” of 1648, and his famous “Hundred Guilder Print” of 1649 (Figure 10). In this work, we find Rembrandt’s most powerful expression of the ecumenical principle, or agape, embodied in the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia: that the greatest good, was to act for “the Benefit, Honor and Advantage of the other.”

In Rembrandt’s etching, also known as “Christ Healing the Sick,” or “Bring the Little Children unto Me” (and sometimes referred to as “Christ Preaching”), now, the Jewish Christ, clearly based on the “Faces of Jesus” (Figures 7-9), is at the center of the composition; he is radiant, illuminated by his love of the people who have come to be healed, both physically and spiritually. As in the “Supper at Emmaus,” he is framed by the suggestion of a large arch, which creates a chiaroscuro effect against the brightly lit scene in the foreground. The New Testament passage that Rembrandt has chosen to illustrate is from the Gospel of Matthew (19:1-30): “And great multitudes followed him; and he healed them there.”

The multitudes enter through a gate at the right: Here are the sick, the crippled, the aged, who beseech His help. At the left are the Pharisees, the Jewish sophists, who hope to discredit Jesus, with spurious arguments. In front of them, two mothers approach Christ, offering their children for His blessing, as Peter (who looks ever so much like images we have of Socrates), at Christ’s right hand, tries to hold the women back, but Christ reproaches Peter: “Then were there brought unto him little children, that he should put his hands on them, and pray: and the disciples rebuked them. But Jesus said, ‘Suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me: for of such is the kingdom of heaven.’ ”

Figure 10 Metropolitan Museum of Art/Havemeyer Collection

“The Hundred Guilder Print” (“Christ Healing the Sick”), Rembrandt, 1649.

|

Seated between the two women, a youth is deep in thought; he is the rich young man who came to Christ seeking eternal life. Jesus tells him: “If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come and follow me.” But when “the young man heard that saying, he went away sorrowful: for he had great possessions.” Jesus tells his disciples, “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of Heaven.” And if you look hard, as the crowd enters from the right, among them, there is the camel, just inside the gate!

Rembrandt conveys Matthew’s summation, “Many that are first shall be last; and the last shall be first,” by presenting the poor and the sick with more precise definition, and greater substance, than the rich and powerful. In doing so, he gives us a rich visual metaphor for the principle of agape, so beautifully enshrined in the Treaty of Westphalia.

[1]. Emmaus was an ancient town located approximately seven miles northwest of present-day Jerusalem.

[2]. The exhibition, which was first shown at the Musée du Louvre in Paris (April 20-July 18), will makes its final appearance at the Detroit Institute of Arts, from Nov. 20, 2011, through Feb. 12, 2012.

[3]. See Bonnie James, “Rembrandt’s ‘Thirty Years War’ vs. Anglo-Dutch Tyranny,” EIR, Jan. 26, 2007 (http://www.larouchepub.com/eiw/public/2007/eirv34n04-20070126/60-71_704_culture.pdf). In 1656, Dutch East India Company shares plummeted on the Amsterdam Exchange and many investors were ruined. Among them was Rembrandt van Rijn, now 50, who was declared bankrupt and whose possessions were put up for sale. In 1657, Rembrandt was forced to sell off his house, and his entire art collection, which he had spent a lifetime gathering—dozens of Dürer and Mantegna prints; copies and engravings after the greatest works of art in Italy—those of Leonardo, Raphael, and others, as well as a quarter-century’s production of his etched copper plates.