Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus

by Karel Vereycken

June 2011

Art Exhibition

Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus

The Louvre in Paris, France

June 2011

This wonderful exhibit, currently on display at the Paris Louvre (until July 18, 2011) will travel to Philadelphia from August 3 until October 2011, and will be at the Detroit Institute of Art, from November 20 until February 12, 2012.

In July 1656, the Supreme Court of the Netherlands issued to Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), as part of a bankruptcy, a cessio honorum, a legal document ordering the Dutch master to organize his belongings and furniture. Some days later, legal officers drew up an exhaustive inventory of the contents of his house at the Jodenbreestraat, currently the Rembrandthuis in Amsterdam, to the benefit of his increasingly aggressive creditors.

The 1656 inventory reveals the splendid collection of artworks belonging to Rembrandt: sculptures, prints, engravings, drawings, and paintings of the most brilliant masters of the Italian and Flemish tradition, of which he considered himself to be a representative, without forgeting of course the vast number of artworks of his own making.

The inventory mentions two paintings of the heads of Christ. In the small studio, "A head of Christ from life," that is, painted after a live model.

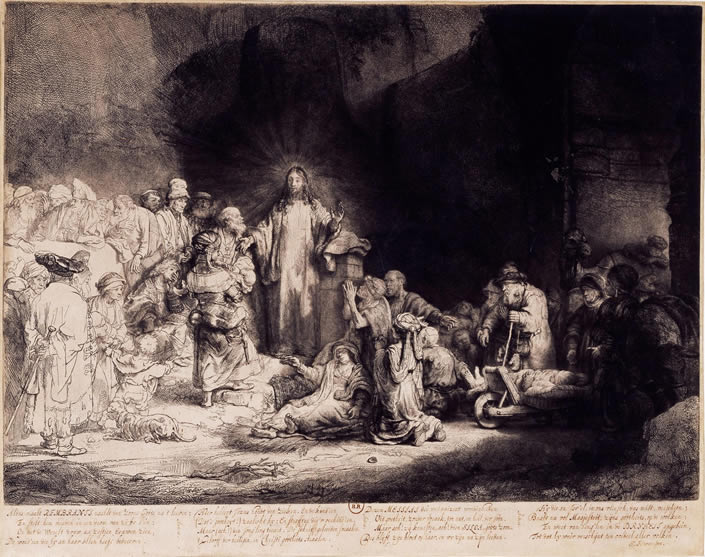

That description also appears in the first phrase of a poem of Herman Frederik Waterloo, inscribed on a copy of one of Rembrandt's most famous engravings, "The Hundred Guilder Print": "Aldus maalt REMBRANTS naaldt den Zoone Godts na 't leeven" ("In this way, Rembrandt paints the son of God, from life"). While generations of art historians have wondered about this paradox: How is it possible for a painter to paint Christ after a living model? The exhibit, by displaying some 85 works of his the master and the great artists that influenced him and his pupils, tries to solve that mystery.

The exhibit approaches the solution to the paradox as one would a thoroughly composed piece of Classical music, both starting and ending with a painting of the same subject, having Christ at its center: the famous New Testament story of the Supper at Emmaus. The story involves two of Jesus's disciples having learned that his tomb was found empty that morning. While discussing events of the past few days, they are approached by a stranger who asks them what they are discussing. They do not recognize the stranger, who soon rebukes them for their unbelief, and gives them a Bible lesson on prophecies about the Messiah. On reaching Emmaus, they ask the stranger to join them for the evening meal. When he breaks the bread, their eyes are opened, and they suddenly recognize him as the resurrected Jesus.

When Rembrandt takes up this subject in 1629, in a painting now belonging to the Paris Museé Jacquemart André, he is only 23 years old. The second version, belonging to the Louvre, dates from 1648, the very year that the Treaty of Westphalia opened the eyes of the world powers, and ended the Thirty Years War of religious strife, simultaneously breaking the yoke of the Habsburg Empire. Traveling between these two paintings, allows the visitor to follow Rembrandt's intense creative and cognitive battle to fully grasp the concept of Christ.

In the 1629 version of the "Supper at Emmaus," the viewer only sees the profile of an imposing Christ, starkly contrasted against a source of light behind him. The enlightened face of a disciple shows his terror and unbelief, while another falls from his seat. Here, as in Rembrandt's "Resurrection of Lazarus," or in "Christ Driving the Money-Changers from the Temple," Christ demonstrates his full authority.

But Rembrandt was influenced by the religious renewal of the Devotio Moderna promoted by the Brothers of the Common Life, and later, by Erasmus of Rotterdam, for whom man, instead of expressing a mere passive admiration, has to imitate, in a far more profound and personal way, the life of Christ. He thus rejected the Baroque style dominating his century. Up till then, other than a few exceptions, among whom was Pieter Lastman, who trained both Rembrandt and his friend Jan Lievens, painters usually depicted the Messiah in a state of glorious beauty, with regular features, and a fancy beard and hair—a person who, even on the Cross, while showing some pain, remained, overall, impeccable.

Some examples of that iconography, among which, some wonderful etchings of Albrecht Dürer and Andrea Mantegna, are to be seen at the exhibit. But as early as 1631, Rembrandt's images of Christ are far different from the standard representations of the time. While Rubens renders Christ an athlete, Rembrandt's Christ is anything but, with skinny arms and a belly slightly distended. As a martyr, Christ's face isn't a fancy piece of aesthetics, but the face of real human being steeped in suffering. If Rembrandt looks to the human aspect of Christ, he doesnt neglect his divine nature. In various drawings, done in ink or red chalk, Rembrandt will explore images of the Christ, for example in dialogue with his followers or with Martha and Mary. Here, Jesus looks both diaphanous and familiar. Without the halo above his head, one could believe this is normal family scene. In one painting, when the resurrected Christ appears, Mary Magdalene at first takes him for the gardener, and Rembrandt paints him with a spade and a sunhat. But the real shift, considered historical, starts when Rembrandt, with a group of pupils, completely taken in by his powerful mind, begins doing portraits of young Jews and rabbis of Amsterdam, in order to get a better idea of what Jesus and his followers might have looked like.

At the center of the Gospel, the figure of Christ is totally paradoxical. Isn't he the King of the Jews, while crucified with the complicity of the Jewish Pharisees? Also, isn't he, at the same time human, and equally the unique Son of God? Rembrandt teaches us again and again that to reach toward God, one has to reach toward man and love what is divine in him, i.e., the soul or spark of creativity that unites him with the Creator. In a final stretto, the exhibit offers the visitors, for the first time in 300 years, seven sketches, including oil sketches, of a young Jew, preparing the final Supper of Emmaus.

Sitting in front of a dark background, Christ is presented with the same brown clothing. Soft light illuminates a face expressing various emotions, from suffering to moments of reverence. The eyes are lifted, the head rotated. Here is the same face, with its dark eyes and high cheekbones, of the young Jew. Intensely human and moving. At last, the Christ incarnate.