SCHILLER INSTITUTE CONFERENCE

Building A World Land-Bridge:

Realizing Mankind's True Humanity

Thursday, April 7, 2016, 9:00am - 9:30pm

NEW YORK CITY

Panel III: Classical Culture: The Only Basis for a Dialogue of Civilization

The Unity of Calligraphy, Poetry, Painting, and Music in Chinese Art

presented by Ben Wang

EIRNS/Stuart Lewis

Ben Wang, addressing the April 7, 2016 Schiller Institute Conference in New York. |

Program and video

Invitation

A PDF version of this article appears in the April 22, 2016 issue of Executive Intelligence Review and is re-published here with permission.![]()

Download slides used in this presentation

as a Microsoft Power Point file (2.27 MB)

Dennis Speed: I met our next speaker, although he didn’t exactly know that he met me, at the Metropolitan Museum, where he was sharing the lectern with another presenter, an American, who was insisting on presenting, shall we say, a slightly veiled quasi-political agenda; but our speaker was able to gently persuade the audience that, perhaps, there was a deeper function of culture, than a political bludgeon.

Prof. Ben Wang is an author, translator, and senior lecturer in languages and humanities at the China Institute of Columbia University.

Prof. Ben Wang: Those are hard acts to follow. [laughter] I brought some Chinese tea. I think I should serve each speaker a little bit for five minutes, and then I will start making my much lesser talk, and people will bear with me. As it is, I have to speak right after them, so I feel a little nervous. But I’m sure you will give me a lot of allowance.

We’re talking about things old and gone away, but as my favorite writer of England, Muriel Spark says, “The glory of the past is the inspiration for the future.” So, although we are talking about something old, I know something new will be born. As Tennessee Williams says, “Violets in the mountains have broken the rocks,” which is written on his tombstone. There’s always hope. But tonight we talk about the glory of the past.

What I’m going to talk about is called Literati Painting, which is uniquely limited to Chinese culture. Because of the time limitation I will have to read. Usually, I am given two or three hours. Before I forget, I must thank Miss Lynn Yen and the Foundation for the Revival of Classical Culture, and Dennis, of course, for letting me come, for which I am very grateful. I begged for more time, but after much negotiation, much talk on my side, I got ten minutes more. [laughter] They were going to give me twenty minutes; I said, “it’s hardly enough, because I’m a master of digression.” So when I do, you must stop me. But seeing how old I am, I know you won’t, but I want you to! Just say, “stop,” and “go ahead.”

Because there are other wonderful,— this is a very rich night! You know, in fact, I’m not trying to kiss up to Miss Yen or the Foundation or Dennis, but I don’t remember attending an event like this. In my totally ignorant idea about speeches, about events, I was usually the only speaker, and the topic is usually on poetry, on Literati Painting, on drama, on music, on theater. So to have such a rich program—I mean, the two before, took my breath away! And after the tenor, I just said to myself, “How can I go on talking?” you know? And my voice, I’m under the influence of a cold, but normally, I sound very good—almost as good as him. [laughter] Not quite . . . maybe 60 years ago.

So, what is Literati Painting? It is,— I’m sorry to say, it might be very unfamiliar to a Western ear. It’s all these three ingredients: poetry, calligraphy, and painting. Now, as shown on the screen:

Poetry, held in the highest esteem in Chinese culture, is the most significant of the three components—poetry, calligraphy, and painting—that make up the genre of Literati Painting of China, which was created during the Song Dynasty (960-1280), from the late 10th century until the late 13th century, before the Yuan dynasty. Literati Painting reached its pinnacle with the patronage of one of the first and most eminent Manchurian emperors, Qianlong (1736-1796) of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

Now at this juncture, I must make something clear: Long before Literati Painting emerged, China already had 2,000 years of culture and civilization. So why did it take so long for Literati Painting to emerge? Because every literary or artistic genre is like a baby: Chinese Literati Painting is a lovely baby. Where does a lovely baby come from? From a lovely man and a lovely woman. And the two of them, they have to be grown up in order to be in union, to be married and to have the child. Because Literati Painting consists of three ingredients: poetry, calligraphy, and painting. So it took the Chinese almost 2,000 years for the three forms to mature, for poetry to mature, for calligraphy and painting to mature, and then, the three in union, they create—the three of them—a grand ménage à trois. They create this lovely baby that is called Literati Painting. That’s why it took so long!

There Is Everything In It

During the period between 1100 and 500 B.C., the first collection of 300 poems appears on the scene, which is the earliest human poetry ever in world history, which is called Book of Songs, as it is translated by Arthur Waley. It still makes very good reading. Well, wonderful literature doesn’t die, quite like an old soldier, it doesn’t die. And so, if you find a copy of the Book of Songs, by all means, read it.

Painting didn’t start until about 300 B.C. And calligraphy matured; it started as oral language and then seal types, and finally, the current writing. And speaking of which, we must go back to the special, unique quality of the Chinese language. All languages in the world are unique. But for something nonpareil, Chinese language is that: quite nonpareil, in that spoken Chinese is music, and written Chinese is painting. That’s why in Literati Painting, there is everything. There are tones, which actually are music, and there is poetry, and there is calligraphy, and there is painting. Actually, painting serves as the supplementary aspect to this genre.

So, let’s go on.

Fusing poetic profundity, calligraphy and tonal splendor, and painting of poignancy, Literati Painting blooms in an enchanted garden of literature, music, and fine art—a garden that has been treasured by the Chinese and the world for the past one thousand years.

This lecture focuses on two timeless works by Qi Baishi.

There have been hundreds or thousands of works, but I have selected only two. If you want to know why, take it up with Lynn Yen and the Foundation. I had 200 prepared; I can speak of only two. [laughter] I’m just joking, feebly. Someone says, “Oh, always blaming someone else.”

Qi Baishi—please remember this name. He is the last giant of Literati Painting. I often say, with his demise, with his death, came also the death of Literati Painting: Because no one can even write poetry, can even write Classical poetry, in Chinese any more. He is the towering master of Literati Painting of the Twentieth Century. An in-depth study of the nuances and underlying imageries and the exquisite musicality of his poems, as well as the refinement and beauty of his calligraphy and paintings, will enable us all to heighten the pleasure of appreciating Chinese culture.

About Qi Baishi (1864-1959). Qi Baishi’s world of art transforms the commonplace of life into poetic romanticism. Born of a peasant and bucolic origin, Qi Baishi produced works which are filled with a sense of closeness to the land, which is well captured in his extraordinarily poignant depiction of shrimp, fish, wildflowers, and birds, among other seemingly inconsequential objects of nature. Added into those paintings are his poems and calligraphy, both of which are marked by an unrestrained bravura and spirit.

Qi Baishi’s acute sense for the colorfulness of nature, employed to reflect love, life, memory, and the transitoriness of beauty and art, affords him the surest passport to immortality.

Now let’s look at the two works by him, which I would say is the main course of this feast.

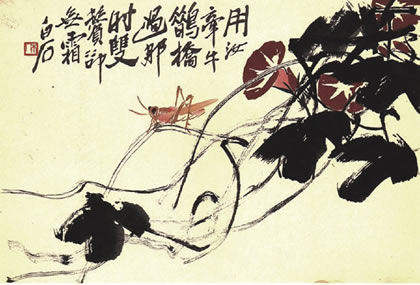

This (Figure 1) is a painting of morning-glories, and this grasshopper is brown, light brown, which means it’s very old; because young grasshoppers are very green. Only when they become old (like myself), does the color fade until finally they become whitish. So this grasshopper is not dark; I mean, grasshoppers are never dark, when they are very young they’re green, but this one is light brown. And he morning-glories are deep purple, between purple and burgundy red. This is the morning-glory. So this is the painting.

Where Does the Meaning Lie?

FIGURE 1

|

The great Chinese artists, they walk a thin line between likeness and unlikeness. To have their paintings look exactly like the real thing, would be too much, too close to realism. They must transcend realism and reach magical illusionism. So this is between likeness and unlikeness, between realism and magical illusionism. So, the grasshopper is coming out of the bushes of the morning-glories. We all know that morning-glories only open in the morning, and when the Sun almost reaches the middle of the sky,— but when we’re approaching noon, all the morning-glories wither.

And pay attention to where he is walking to. He is lowering his head toward the west. Chinese culture is heavily influenced by Indian art; so before, when I was listening to Tagore’s poem, although I don’t understand Bengali, yet I could be moved: That’s what poetry and beauty can do, even if you don’t understand the language. For instance, when we listen to opera, I don’t really, always, understand what’s being sung, but I can appreciate the music.

So to the Chinese, the west is Nirvana. We call it the World of Extreme Happiness,— so that means the grasshopper is old, and he has experienced all his happy and healthy golden days; now he’s walking toward the west, to Nirvana,— to put it plainly, to death.

And there are two lines of poetry. These are heptasyllabic lines.

So these are two heptasyllabic poetic lines, a poetic couplet. In Chinese the most popular poetic styles are either pentasyllabic or heptasyllabic, meaning five characters per line, or seven characters per line. The Chinese language is a monosyllabic language: Every character, every word-character has only one syllable, so when I say, “heptasyllabic,” that means seven characters per line.

So you look at this painting, you feel—wow!—it’s a mixture of tenderness, exquisiteness, and something bravura, because of the brushwork. Yet, what is important does not lie in the picture or in the grasshopper or in the morning-glory, but they are all serving as supplementary to the poem.

So he put down these two lines. What exactly does it mean, “Use you Pull Cattle (in capital letters) Magpie Bridge (capital letters) pass”? Then, “Then two temple but no frost”? What does that mean? Maybe that’s what makes the non-Chinese, the Westerners, ask, What are you saying? Are you speaking Chinese? [laughter] You know? Because it defies understanding, unless you understand Chinese—except this is Classical Chinese.

So the artist is addressing directly to,— he is the grasshopper. The grasshopper has taken the persona of the poet. So he has just come out of this. So he is talking to the morning-glory. He says, “I have once used you, I have employed you. You are the one who helped me, you are the Pull Cattle flower.” Morning-glory in Chinese is called “Pull Cattle.” Why do you think the Chinese would call the morning-glory “Pull Cattle?” Because morning-glory only blooms, only opens when the Sun is up, when it’s the crack of dawn it starts to open. So it’s time for the Chinese farmers to pull the cattle, to pull the water buffalo out to work the field. So the Chinese said, “Oh, these flowers, they should be called, ‘Pull Cattle’ or call for cattle to wake up and help us, drag us to work on the land.” So in Chinese—that’s why it’s in capital letters—“Pull Cattle” is the Chinese name for morning-glory.

So, once upon a time, I used you, my dear Pull Cattle flowers. And you have helped me pass the Magpie Bridge.

Now, there’s another folksy and also literary allusion to this. And the magpie is connected with a very sad Chinese story which is not unlike Romeo and Juliet. It’s about a thwarted pair of star-crossed lovers. They can meet only once a year, and the woman is a celestial being, so she’s a weaving-woman in the celestial palace; she comes down to the Earth, she meets this shepherd boy. He tends to cattle, so he is a cowherd, the Chinese answer to a cowboy. So they fall in love, but she is a celestial being, so she is called back by the king of the celestial palace,— so they can never meet again. One old buffalo takes pity on them, and when he dies he says to the shepherd boy, “you’ve been so sweet to me, and I like that girl, the celestial being that you married who has gone back to the celestial palace. So after I die, you cut my hide and every year, on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, you wrap my hide around you, then you can fly. So I will help you to fly into the sky to meet with your lover.”

What Is It About?

And in the meantime all the magpies, they took pity on these two thwarted and star-crossed lovers, so in the firmament, in the Milky Way, there is a river which is called Silvery River, and the magpies, in flocks, lay in the river—the river is not that deep. So that allowed the shepherd boy to walk on their bodies to go across the bridge to meet his loved one.

So this is the story. So he said, “My dear morning-glory, once I used you to cross the Magpie Bridge. But alas, at that time, the two temples on my head . . .” this temple is not a Buddhist temple; it is this temple [points to his head], the two sides. That’s where the white hair, like my hair, first grows. It usually starts with the temples.

“But at that time, the two temples of mine, there was no frost on them.” To the Chinese why did hair turn white? Obviously Heaven has sent some frost onto your hair, so your hair turns white.

So this is referring to the white hair.

What is this painting all about? It is the remembrance of lost love, of lost happiness, and golden, healthier days, everything that is lost,— but once upon a time, there was love, there was beauty, so it’s worth remembering. So instead of crying, or any lamentation, or any lugubrious message to feel saddened by this remembrance, the artist uses this very discreet way of expressing what is on his mind. Remember, all great artists can never forget that human beings are the basic subject of all art. So out of poetic imagination and great compassion, they spin loving, poignant, and luminous works. This great Chinese master of painting, calligraphy, and poetry is no exception; here is this seemingly non-human composition, referring to everything in the human mind about remembrance.

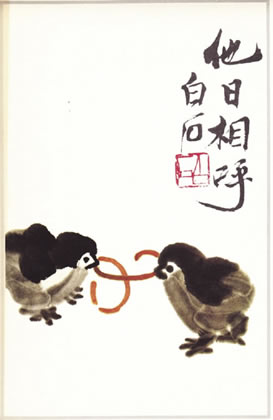

And now quickly we come to the finale. This one is one of Qi Baishi’s signature pieces and masterpieces, I would say. In 1948, right after the Sino-Japanese War, when China suffered from unprecedented invasion and the cruelty of a savage war of eight years, it was immediately followed by a civil war between the Communists and the Nationalists. Full of painful sentiments and emotions about what is happening around him, Qi Baishi, being an artist only—he’s no politician, no great military man—what can he do about the bad times that he was living in, era after era, decade after decade?

FIGURE 2

|

So, in desperation and in sadness, he composed this painting (Figure 2). And you see two chicks, and he deliberately leaves out the tail of this chick [on the left], so the composition of this painting is a little more interesting. It’s less pedantic, I would say.

And also, do you see how they stare at each other? And this is all brushwork. And here is the earthworm they’re fighting over. And so, is he really painting two chicks for us, for the viewer to enjoy it? No. Because the heart of the matter is here: Now these four characters are the heart of the matter. And these two characters were his signature. His literary sobriquet was “white stone.” So this is “white” and “stone.” To the Chinese, white represents purity and rock represents perseverance and fortitude.

So these four characters are ta ri hu xiang; this character ta in modern Chinese means “he.” But in Classical Chinese, and it derives from Classical Chinese, it means “the other,” “some other.” “Some other day”: this (ri) is “day”; the picture is “the Sun is rising.” This comes from the Sun. Every Chinese character is derived from a picture, so “Sun” represents a day. So “some other day.” Then xiang originally showed a Chinese farmer’s eye set on a tree, which means he is very fascinated by the tree. He wants to know the age of the tree, what kind of tree it is, whether or not it should be used as firewood or in the lumberyard. So xiang came to mean “to each other” or “with each other” or a mutual relationship. So my translation is “to-each-other.” Hu is call out; the mouth is the radical, so this is to call out, “hellooo!” And how does he express this “hellooo,” the echo? By moving this stroke all the way around like this. Normally when you write this stroke, you just go up to here, you go up a little bit. But yet, he goes all the way around.

So, in 1948, when the Civil War was going on, he was heartbroken! So he was saying, “Communist Nationalist or Nationalist Communist, now you’re fighting for the land of China. But remember, we’re all Chinese. One day, I hope—you’re both chicks now—some day, when there is a stormy day, or blizzard, or rainy day, but you will grow up to be a big rooster, and so will I. We are brothers, we’re siblings, we grew up together. Now we are very ignorant, we’re small babies, we fight over an earthworm. But some day, when we grow up, no matter what the day is, if you call from the neighboring village two miles away, I will hear you, I will call. I will say, “Hey, Brother, are you still there?” And so the other rooster will say, “Yes, I’m still here, and I wish you well.” So we’ll still be siblings. We will remain siblings.

Visit worldlandbridge.com |

This is the great artist’s hope, his compassion, his passion, his wish for the two parties that were in a bloody war, to come to a peace. Or, maybe not in his lifetime, but one day, when they grow up. And now, for sure, the President of Taiwan has gone to meet with the President of People’s Republic of China, and I think Qi Baishi’s dream has come true.

So this is seemingly,— he uses painting, art, to talk about politics, to talk about war, to talk about human fights as strife, the disgusting war, the bloody war; but he uses beauty and art and poetry.

I know I have run more than 35 minutes, so I really must quickly come to an end. I will say something else, that my favorite Tennessee Williams, the greatest poet-playwright of America in my mind, in my opinion, says, “what implements have we, what words, images, colors, music, scratches upon our caves of solitude?” I think Qi Baishi, if he had heard these words, would have been in total agreement with Williams. Thank you very much.