Classical Music:

The Highest Expression of Creativity

Schiller Institute Conference

Concluding Panel

February 2012

Presentations:

Art and the Logos by Antonella Banaudi

Four Generations in A Family of Musicians by Raymond Björling

Thinking Without Words by Shawna Halevy

Classical Music And Scientific Discovery Excerpt from Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr.

EIRNS/Christopher Lewis

Helga Zepp-LaRouche welcomes Swedish tenor Raymond Björling to the Schiller Institute conference in Berlin. |

The Schiller Institute’s conference in Berlin on February 25-26, 2012 [1] closed with a panel on “The Coming Humanist Renaissance.” Helga Zepp-LaRouche introduced it, and the speakers were Italian soprano Antonella Banaudi and Swedish tenor Raymond Björling, whose presentations are published below. Completing the section is a contribution from Shawna Halevy of the LaRouche Basement science team, “Thinking Without Words.”

Zepp-LaRouche started by making clear that this is not some “nice” panel on Classical music, divorced from political reality. On the contrary, Classical culture is indispensable for overcoming the current existential crisis of mankind.

The danger of global thermonuclear war, which was the theme of earlier conference presentations, remains as urgent as ever, she said, as she reported opposition to war against Iran or Syria, coming from U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Martin Dempsey, warnings by Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, and others.

On this background, she said, a paradigm shift is urgently necessary in people’s image of what it means to be human, and their understanding of globalization and the system of empire.

“I think we will only emerge from this existential crisis,” she said, “if we can agree on the common goals of mankind; if we say we shall desist from imperial, geopolitical, chauvinist, racist, colonialist, and similar ambitions, and that we simply say we, as human beings, are united by higher goals than what divides us into petty interests of a so-called geopolitical character.

“The common aims of mankind, as we heard in earlier presentations, include the next scientific frontier in the development of the Arctic and in the development of manned space flight. But it must be associated with a humanistic Renaissance, which advances the ideal of mankind; that democracy is exactly what Plato said; or Thucydides, the first historian, who stated in his book on the Peloponnesian War that the other side of the coin of democracy is tyranny.

“Look at the people today who are supposedly upholding democracy and using it as a pretext for ‘humanitarian’ interventions in the sovereign affairs of other states that are not so democratic, as the EU does for example, or the U.S. Administration, which currently has abrogated almost all constitutional rights.

“Thus, it is not democracy that should be the basis for decisions, where the diversity of opinions, all of which are wrong, never adds up to the right policy; rather we need to reach the point that mankind, or a growing part of mankind, begins to think scientifically, orients its thinking to verifiable universal principles, and likewise to the principles of the great Classical art, because these are just as universal and eternal as scientific knowledge.”

The final panel of our conference, she concluded, is dedicated to this theme: How Classical art fosters the idea of man as a creative individual, who discovers his humanity through the celebration of beauty.

[1]. Covered in previous issues of EIR, and available in video at http://schillerinstitute.org/conf-iclc/2012/berlin/main.html

back to top

LaRouche: Classical Music And Scientific Discovery

The following is an excerpt from the LaRouche Weekly Report of April 18, 2012.

The definition of Classical composition is exactly this: that Classical composition actually produces a result which is expressed as human creativity. But it is expressed as if it were coming from the future, into the present.

Then you look at living processes, and you that see the concept of life also works as coming from the future into the present, in which you’re looking backwards. You look at nonlife, when called nonlife, you look at that as clock-time, one clock-time. When you look at Classical musical composition, and its creativity, your sense of it is in reverse. You foresee the effect before it happens! That’s the essence of Classical composition. And that’s also the characteristic of all actually creative human activity.

Every discovery of principle occurs exactly in the same form as Classical musical composition. You start with a problem; you get an idea, think it through; and you get to a point, and suddenly, you get a breakthrough! And you find that you are actually anticipating the future, with respect to the present. The same thing is true of life: You never get life from nonlife. You never get creativity from mere life. Our understanding of the universe is in that order.

And therefore, as we enter the challenge of the Solar System, and beyond, we go from what’s called a chronic system, but once you enter into this area, you don’t have a chronic system any more. And therefore, we have to redefine our view and definition of the universe and its principles, as a working universe, because the normal sense of space and time, no longer exists. As Einstein already saw, space and time are qualities which people believe in generally, but which do not actually exist, as Einstein’s proof demonstrates it.

So therefore, you look at it with aid of Classical musical composition, and how the person who’s performing it, or experiencing it, responds to it: that when they foresee the solution for the composition, they get an anticipation of discovery, before they arrive at the discovery in a normal way. In other words, they start with the score, but they do not deduce the composition from the score. The discovery itself defines the discovery—that is, you get this déjà vu sense—you experience this—and this is the principle we’re fighting with and the principle we’re dealing with. That obviously, the universe is organized in this way, and our existence proves that. The problem is, that we are not conditioned to think in this way, and therefore, we use a kind of thinking which does not correspond to reality.

Art and the Logos

by Antonella Banaudi

Here are excerpts from soprano Antonella Banaudi’s speech to the Schiller Institute conference on February 26, 2012. It was translated from Italian.

The title for my “expressions” is: “Education as Singing, and Singing as Education.” It will probably be more of a free digression than an orderly journey. As someone once said: Speaking of music is like dancing architecture.

I would like to recall some words that have become part of our culture and can be understood outside of any specific religion: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God.”

The “Word” does not mean a word in the strict sense that we mean it today. The Word is sound, the vibration of all that is alive, and thus means life and creation, and creation is the language of the Creator. Logos is the medium of all form. The Word is total knowledge of the absolute, beyond appearance. The Word is the word of God who names things, makes them evident, the Principle to which every person aspires….

Now I do not want to enter into a sterile debate which counterposes music and words, on which of the two must serve the other. I think that a musical genius is a person who is able to reveal the soul within the envelope of the words, who can translate the secret of the poetry into the architecture of sound. And it doesn’t matter how the word is treated as human language, or if it is split up, broadened, even torn apart, taking it far away from our common manner of using it.

I would like to add a reflection, maybe a hint of a reflection: Music is the intermediary between word and principle. Words without music are not poetry. Music without poetry is not the Logos….

The Poetry of Art

Any type of study is a process, an enterprise of improvement. Art, however, is a process aimed at improving oneself, but not as something unconnected to reality. Art must not be used to detach oneself from reality, to find a solitary Eden of sterile and ephemeral beauty. The improvement of oneself also leads to the improvement of what is around us.

There is no distinction between spirit and matter. They are only different levels of perception of reality. Art can unite physical reality and transcendent reality. Art puts us in contact with the Principle, with the Logos understood as reason and ratio, and what is music if not reason and relationship? It puts us in contact with what Heraclitus defined as Lightning—Fire in the sense of continuous genesis, Immanence. Music, above all, can put us into contact with Immanence, with the eternal soul that constantly re-creates itself.

In our lives we have the gift of being able to be illuminated through art and the poetry of art, of experiencing the meaning of a moment, of this cosmic breath of which we are a part. Art educates our soul, the essence that must be constantly nourished and re-created.

This search for beauty and reason is, in itself, a beautiful adventure, and it is even more beautiful to share it with other “adventurers.” Through song, we live this invaluable experience; we are instruments of ourselves. We can create the sound in each moment, and to do this, we must learn to experience it tirelessly, even with nimbleness and luminosity, vital but also black, but totally. Only by performing great music or listening to it performed by great musicians can we experience this continuous moment, even in the construction and organization of everything, in a vital tension towards the infinite.

Do you recognize the urgency, the mad drive toward aspiration, constructed and fueled moment by moment, with every sound and melodic line and harmony and color, dense and tense even in silence, until the final Presto of the fourth movement of [Beethoven’s] Ninth Symphony?

Well then: How can I learn to live every fraction of a moment so intensely? It may seem obvious, but it can be learned by educating ourselves with practice, with patience and method, improving concentration, the capacity for interior visualization in the constant search for the best, from an aesthetic, physiological, and expressive standpoint, with the flexibility to invent and experience new paths, with a constant assimilation, but also contemporaneously with projection toward the future, ready to imagine the next moment.

The Study of Singing

Now I would like to shift to a more practical terrain, since I have to respond to the questions that have been posed to me, and which you may also have.

EIRNS/Christopher Lewis

World-renowned Italian Soprano Antonella Banaudi demonstrates her art at the Schiller conference. “The study of singing,” she said in her speech, “is a privileged form of education, because it belongs to art, and thus to a creative process.” |

The study of singing is a privileged form of education, because it belongs to art, and thus to a creative process; because it belongs to music, and thus to the vibration of the Principle; and because I myself am the instrument of transmission of the secret (fortunately the great composers have given me this possibility).

And now, let us begin to educate ourselves. We start by eliminating preconceived ideas about our own voice (the greatest discoveries were made precisely because scientists were able to “forget” prior progress, and not be influenced by it, to be courageous and brazen in challenging preconceived ideas, constructing their own personal vision of the world). And so we start to do this in our own small way! When we study, we must be completely open to finding what our voice really is. Study for a certain “result,” for example, the power of sound under the illusion that we can do without the other requirements of bel canto, will lead to a potentially ugly voice, which nobody will want to listen to.

Pursuing agility at all costs will make us superficial and boring. I still remember how a young woman, a light soprano, wanted to impress me with a very fast performance of a famous aria. What I actually heard was a soprano that was more superficial than light. Passing over a beautiful passage at supersonic speed, only quick flashes of color remain in your memory, which are completely insignificant.

Respect for your own voice means respect for yourself.

The attitude that we have toward it is the mirror of how we deal with ourselves. I am not only speaking of the aesthetic aspect of the voice. I am speaking of vocal personality and its artistic effectiveness, its capacity to transmit a vision with its own language, an idea, a meaning and an ideal creation that goes beyond what is evident.

Returning to the supersonic speed: In my view, in music and in art in general, the best results are achieved when you go slowly, especially at the beginning. Painting begins with the cleaning of the brushes, the preparation of the canvas, the mixture of the colors, painting a background, some angels, the drapery of a garment; how much study was needed to paint the flesh of a face? An eye? Apart from the laws of ratio and proportion between figures, the study of light, to come to express its … Secret, including through a hidden teaching?

Why Study Vowels?

I sense that at the beginning, some of my students are surprised at how much time I spend on the study of vowels. It is a slow process, a continuous process of listening, for the training of the inner ear, for a continuous process of exclusion of what is less beautiful, to lighten the path, to be able to choose the best, in a continuous process of experimentation, always referring to what we have found that is beautiful, because the beautiful is our guide. It is a study of the beginning, and then, the repeat of it, for each new piece that we intend to perform.

Almost nothing that is art is taught theoretically. We can only teach and experiment and choose that which takes us down the best path and the right path, the only one which reflects inner truth. A great artist is one who is able to be himself while participating in Truth, in Principle.

This is why I believe that the study of singing does not involve an aesthetic choice, but a moral one, in the sense of truth joined with goodness and beauty.

And thus for me, through the study of vowels by the student, and the study of the student herself, we reach a balanced position to obtain a bright and lively voice, even in the darker portions, with legato and flexibility and agility, so that the instrument is able to partake in the idea that governs the world. The voice does not give sound to words; it gives sound to the inner meaning of a composition. Each time must be a rediscovery and re-creation, with the sense of marvel of the original sound through the Word.

Our spirits must participate in the music through the voice. And we can only do that if our technique has become transparent with musical emotion, in communion with the color of the idea. I don’t much like the word “interpretation,” because it could be confused with an interference that is too strong, in our partial vision of the idea expressed musically. I prefer “partaking” in the musical emotion.

EIRNS/Helene Møller

“The study of singing does not involve an aesthetic choice, but a moral one, in the sense of truth joined with goodness and beauty,” said Banaudi. Here, she conducts a master class in Boston in 2008. |

At times it is very simple to change the color of a voice. I remember a calculated, ponderous, and also boring execution of “Già il sole dal Gange.” Just think of a film clip of the Sun that rises over the Ganges, with its clear shine, and let yourself be taken by the movement of the music, like a boat on a wave, and immediately the quality of the sound changes, in an easier, and happier execution! This is a very simple example. I can say that until our imagination is shaped by that which the author has translated into music, we will not achieve an artistic quality of performance.

Only if we know our own nature can we educate it, improve it, strengthen it, be artists of ourselves.

Perhaps I can compare the study of singing to a sort of knowledge of the house in which we live.

At the beginning it seems that the light is sufficient to live in, but we don’t know exactly how it is built or what is inside it. We use the same areas, the same chair, … but then we begin to discover the rooms, clean them, throw off prejudices and habits, and useless and troublesome furnishings. We open the windows, let in the light; we are no longer content with artificial light. We need true light, that of the Sun, our fire. Usually a house that has been cleaned and ordered is much more beautiful than we had considered in the semi-darkness, neglected because of distractions or other reasons. Often we discover that we like it better this way, we live better than before, we breathe more easily, and people are happy to come and visit us.

The Pazzi Chapel

And now we come to the final digression: I recently went to the Pazzi Chapel, in Florence of course, the Florence of Brunelleschi and Ficino….

In its naked proportion and simplicity, in the balance of light and colors, it gave a beautiful resonance to the sound of my voice: a demonstration that it is the proportion, the idea translated into construction, that resonates inside of us. The emotion I felt in hearing a response from the stone, that almost supported me in singing, as if the stone were alive, and expressing itself through cosmic vibration, made me feel part of a whole that unites stone and man, in a harmony that is the reason for the existence of everything. It is the same harmony that we seek and experience when singing together, playing together, participating in a sort of rite/celebration that is beyond religion, and is profoundly moral and human.

Four Generations in A Family of Musicians

by Raymond Björling

EIRNS/Christopher Lewis

Raymond Björling addresses the Schiller Institute conference, with a photo of his grandfather Jussi Björling on the screen behind him. |

Raymond Björling, a Swedish opera singer, and grandson of the world-renowned tenor Jussi Björling (1911-60), spoke at the concluding panel of the Schiller Institute conference in Berlin on February 26, 2012. [1]

It’s nice to be here in Berlin, it means a lot to me. When I was seven years old, we moved here to Berlin—me, my mother, my sister, and my father. My father was a good opera singer and he was engaged at the Deutsche Oper, here in Berlin, where we lived in Königsallee, near the big forest, Grünewald. It was a fantastic time, because we came here straight from America, where I was born in 1956.

My father made his debut in 1962 in Göthenburg, Sweden performing as Pinkerton in Madame Butterfly, and then he was engaged to move down here, where I went to the Deutsch-Amerikanische JFK-schule, where I learned to speak the language fluently in those days, which is one of the reasons I am back here.

Ulf [Sandmark] wanted me to speak on singing and my background, but it is so interesting to learn that the LaRouche movement is integrating music and art into its political work. That is fantastic, because music and art are so very, very important to human beings, more than we would actually believe. It has been the main purpose for my family.

Great-Grandfather David Björling

My grandfather’s name was Jussi Björling, and he was considered the world’s greatest tenor in his day. The work, however, had begun before Jussi. His father, David, was a great singer, a very special man. He wanted to sing at a very early age, and he was very stubborn. He was only 15-16 years of age, when he started to sing professionally, with choirs, and he wanted to go to [music] school.

His father had a problem with that, because in those days you had to learn a trade. In our family, we were blacksmiths, so David was supposed to become one too, against his will. His father didn’t know what to do with him, because without an education,would not be able to support himself or a family. His father was so upset, that he sent him off to a friend of his, a very tough man, who said he would make a man out of this boy. After a month, though, he sent David back, saying: “I can do nothing with him, he’s too stubborn! He only wants to sing and play music.”

David therefore left his family for Stockholm, where he began to study music. He was a smart man, because every time that the King appeared publicly, David would be there too, singing. The King of Sweden in those days, Oscar II, himself wanted to be a tenor; because he was so impressed with David’s singing, he ended up paying, out of his own wallet, for him to study at the conservatory of music in Vienna. There he studied, got a good degree, and came back to Sweden, to make his debut in Gothenburg, on the eve of World War I, performing Pinkerton in “Madame Butterfly,” as my father did after him. He was a great singer, and I have read the great reviews he received. But when the conductor later tried to instruct him, he refused stubbornly, and therefore, shortly after, his opera career ended, because he was considered too difficult to work with.

Instead, he found work making machines that separate cream from milk, until he grew tired of that, and suddenly, one day, he disappeared. Nobody knew where he went, so that after a few years, a death certificate was almost written out. But he had taken the boat to America, and had started to sing, just to make a living, in restaurants and all around.

Somebody was impressed, and took him to the Metropolitan Opera school, where he ended up studying under [Enrico] Caruso himself. However, when Caruso began to instruct him, he would become very stubborn again, saying, “No, I want to sing in my own way.” At one point, there was a big disagreement, to the degree that Caruso slapped him in the face and David slapped Caruso back, and he packed his bags and went back to Sweden.

In Sweden, they only now discovered that he had been to New York. He went back up north, to Borlänge, Dalarna, and met a beautiful lady by the name of Esthersund. She was singing in a choir, in which they met; they fell in love, and all of a sudden began to produce all of these boys! [shows photo] There had been four boys, but the fourth boy, Karl, died at birth, and his mother died of tuberculosis. Therefore David was left alone with these three boys.

He started singing with them at a very early age, 4-5 years old. He taught them how to sing, and took them out to perform concerts. This constellation was called the Björling Male Quartet, and they sang all over, and the small boys, standing on boxes to elevate their height, would cause many ladies to cry. David would perform with them, although unfortunately, there’s no recording of him—it was said that he had a marvelous voice. As the boys grew older, after a while, he took them back to America.

They toured all over America for 18 months. In the Swedish and Scandinavian regions of the U.S., a lot of people recognized the popular Swedish songs. They became so popular, that you could make an analogy to Michael Jackson and the Jackson family. It was just like that…. It was a very remarkable family, who all sang. Olla, the smallest one, only started his singing career later; my father was an opera singer, my aunt was an opera singer, so I think that we’ve had nine family members who sang professionally.

‘Music Is So Important…’

Music has meant so much for my family, and also gave us a chance to stay alive, by the little money it offered. Music is very, very important, and it’s sad to see the modern culture, the pop culture, that just wants to make a profit and simplifies everything, instead of trying to find art that talks to your heart and gives you something….

A man who has written one of the most beautiful songs regarding art and music is Franz Schubert, “An Die Musik,” which I would like to perform for you….

So, you see music is very important to all of us. Of course it’s very important to us who sing and perform it, but even for young people nowadays, think about how important music can help to soothe people. Music is a universal language, and if you know music, you can talk with anyone in the whole world who understands music. We don’t need scores with notes, we just need the music, and then we can perform together.

That’s fantastic and should be a part of politics in this world, because it can break up the ice. The problem in the world is that we don’t understand each other. If everybody could speak the same language, it would be easier. It’s the same for these boys—these boys didn’t have an education, but with the music, they could perform together. They could go all over the world and people could understand them. All of these three boys became great singers. You have of course heard of the three tenors, but these three boys, actually, could have been the three tenors.

There is something to say about the color of their voices. The only way that their voices differed, was that Gösta, the oldest one, his voice sounded like gold; Ulla sounded like silver; but Jussi had a sound like steel. That’s how they were divided in character, but otherwise, it’s very hard to tell the difference among the three. It came from their father, who had this idea of how you should sing, and that gave them hope for life, and meant that they could travel the world and communicate through their music.

Grandfather Jussi Björling

Jussi started very young; he was only 17 years when he came to the opera school in Stockholm. Now, that is a very young age, so the head of the school, John Forsell, only reluctantly let the boy audition. After performing, Jussi came up to Forsell, who was quiet—not a word was said. After a couple of minutes, he looked up from his desk and said: “Mr. Björling, I cannot do anything for you!” So that Jussi thought that he had done a bad audition, but Forsell continued: “No, I cannot do anything, God has already done everything.” So, he was accepted at the opera school, which was tough for such a young person with all the tough competition, but the quality of his voice was so good, that nobody picked on him, in any way, shape, or form.

One day, when he came late to a choir session in a big church, the conductor told him they could not use him, that he should go home and never come back. Jussi walked out and slammed the door, but then he opened the door again and said, “Okay, I am going, but try to find a better tenor, if you can!”

Jussi Björling (1911-60), was considered the world’s greatest tenor in his day. |

So, he knew of his greatness, and his voice took him all the way to the Metropolitan Opera. This, of course, was a big thing, because when you go to the Metropolitan, you don’t just go to the Metropolitan, but you tour all the big opera houses in the United States. So, in this way he became world famous.

He was back in Sweden during the [Second World] War, and couldn’t go back [to the United States], because he was afraid of crossing the sea and getting bombed, so he stayed in Europe and toured all over. He once sang here in Berlin, after the war, and became a star in Europe.

Once there was a young man in Italy, by the name of Luciano Pavarotti, who listened to one of the old recordings of Jussi Björling and was inspired to try to become as good as Jussi. I met Pavarotti once, and he told me that he would have otherwise become a professional football player. There are pictures where you can see him dressed up for football, very slim and tall. But, then the opera took over, and he became a little bit bigger.

‘I Couldn’t Stop Singing’

All of this has of course colored my life and myself as a singer. I didn’t want to sing, actually, because I grew up in the backseat of a car with my mother, touring all over, with my father in the front seat and a pianist next to him. We did this for a couple of years, which was very boring for a young boy. I didn’t want to have the same kind of grown-up life, where you always have to sit there at the concerts, not allowed to laugh at anything, because it was very serious business.

And so I decided not to start singing. I tried to do something different after school. I tried to become a salesman and did a lot of jobs, up until the day that my father became a little bit nervous about all of this. One day put his arm around my shoulder, looked me in the eye, and said, “Please, you have to try to sing.” I agreed, and then from that day on, I just couldn’t stop. That is what happens when you start with music: It grabs you, and once you’re in there, you cannot leave.

So, I’m here. I’m still going to sing. Now nobody else wants to hire me, because I don’t know anything else apart from singing, but it’s a fantastic world. I want to sing a little Swedish song for you, which can be compared with “An die Musik,” by a Swedish composer named Carl Leopold Sjöberg, and the song is called “Tonerna,” meaning “the tones.” In life, we have a lot of thoughts that go around in our mind and often mess us up, but as the text says, the tones, the music, soothes and heals….

Here’s another picture of Jussi. I am very, very proud of him. Proud to be his grandson. This is my father, Rolf Björling, when he sang here in Berlin. I really wished I could have stayed longer or even permanently here, but times were hard and my father had gotten a job in Sweden, as both he and my mother were longing for Sweden, with their family and everything. We moved back in 1965. My sister, who actually started singing first, was sent to a music school, which I wasn’t, because they thought I was too young. My sister and I then ended up doing a concert together, in which she was so nervous, that she ended up quitting singing completely, even though she had a very beautiful voice. Instead, she became an interior decorator, and works with that and with art in Sweden. My mother is a very good painter, so art is in our family.

Art is not easy, these days, because most people think of it as a hobby, which is really sad, since that holds people back. There’s not much money in art and music, unless you’re a big star, of which there are only few…. That’s something we have to change. We have to see art as something big in our lives, which means something to us. Everywhere you look, there’s an artist behind it, which we tend to forget….

Finally, before I leave, I want to perform one last song, which has always been one of my favourites, namely Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Adelaide.” And that is my final word today. It has been a pleasure talking to you today and I hope to see you all again.

[1]. The video of his presentation is at http://www.schiller-institut.de/seiten/201202- berlin/bjorling-english.html

Thinking Without Words

by Shawna Halevy

A contribution from the LaRouchePAC Basement Team.

Do you think about how you think? How does it occur? Do you think in a sequence of logical steps? If you were to write out a thought, would what you wrote reflect how you came to your idea? Is the end product the same as your thought process? To be clear, we are not talking about just any type of thoughts, such as impressions, a memory, a simple opinion, or an urge, but a principled discovery; something you would consider a profound and fundamental idea.

If you are a teacher, or have tried to communicate a complex idea, these questions have come up naturally to you. Did you find with students or others, that you really couldn’t “just say it,” and expect them to understand the idea? That explaining it doesn’t get them to think it for themselves either?

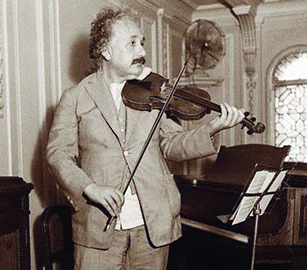

The issue of discovering and communicating ideas has been addressed quite explicitly elsewhere on the LaRouchePAC site.[1] I would like to add to this discussion the simple question: In what form do your thoughts occur? Do they appear in words? Or other types of sensed objects? Does a data-ticker scroll through your brain? Or is it more like scenes from a movie? Before further analyzing ourselves, let us look into another mind. Let’s ask Albert Einstein how he thinks:

“No really productive man thinks in such a paper fashion. The way the two triple sets of axioms are contrasted in the Einstein-Infeld book [The Evolution of Physics: From Early Concept to Relativity and Quanta, by Einstein and Leopold Infeld] is not at all the way things happened in the process of actual thinking. This was merely a later formulation of the subject matter, just a question of how the thing could afterwards best be written. These thoughts did not come in any verbal formulation. I very rarely think in words at all. A thought comes, and I may try to express it in words afterward…. During all those years, there was a feeling of direction, of going straight toward something concrete. It is, of course, very hard to express that feeling in words; but it was decidedly the case, and clearly to be distinguished from later considerations about the rational form of the solution.”[2]

In another instance Einstein addresses the same question: “The words or the language, as they are written or spoken, do not seem to play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychological entities which seem to serve as elements in thought are certain signs and more or less clear images which can be “voluntarily” reproduced and combined. This combinatory play seems to be the essential feature in productive thought—before there is any connection with logical construction in words or other kinds of signs which can be communicated to others. The above-mentioned elements are, in my case, of visual and some of muscular type. Conventional words or other signs have to be sought for laboriously only in a secondary stage, when the mentioned associative play is sufficiently established and can be reproduced at will.”[3]

And to sum it up most succinctly, Einstein writes: “I have no doubt that our thinking goes on for the most part without the use of symbols, and, furthermore, largely unconsciously.”[4]

If Not Words, What Then?

If Einstein doesn’t think in words, then how does he think? He has hinted at it already by bringing up the process of “play,” and voluntary synthesis or combination of thoughts. The discovery of a new idea can be related to a surprise, the “Eureka!” moment. To accomplish this, the imagination cannot be constrained by fixed answers or characterizations, but has to be able to fly past the shadows of experience (the objects that can be pointed to and named), to the unseen.

“I often think in music,” Einstein said. He is shown here with his beloved violin, in January 1931. |

So, if not words, in what means does Einstein think? He pointedly says: “I often think in music.” What does it mean to think in terms of music? Does he have chords constantly playing in his head? Does he see sheet music in his mind? “…when we communicate through forms whose connections are not accessible to the conscious mind, yet we intuitively recognize them as something meaningful—then we are doing art.”[5] This would indicate that music is closer to the subconscious thought process then any other system of language, and therefore closer to the more ideal parts of thought. This makes sense in relation to what Einstein said earlier, about his thoughts being directed, pulled on, as if from outside, to the correct destination.

The same thing happens in the unfolding of a well-composed piece of music. Classical music is a reflection of the tension and resolution that goes into grappling with paradoxes. Hence, why Einstein would say: “Every great scientist is an artist.” As one of his biographers put it: “[Music] was not so much an escape as it was a connection: to the harmony underlying the universe, to the creative genius of the great composers, and to other people who felt comfortable bonding with more than just words” (emphasis added).[6]

Others would agree: To get a better idea of what thinking in terms of music, as opposed to words, means, let us turn to a contemporary of Einstein’s, the Russian scientist V.I. Vernadsky:

“Music seems to me to be the deepest expression of human consciousness, for even in poetry, in science, and in philosophy, where we are operating with logical concepts and words, Man involuntarily and always limits—and often distorts—that which he experiences and understands. Within the bounds of [Russian poet Fyodor Ivanovich] Tyutchev’s ‘a thought once uttered is untrue,’ in music, we maintain unuttered thoughts…. It would be quite interesting to follow in a concrete way the obvious influence of music on scientific thought. Does it excite inspiration?”[7]

It is common to associate moods or feelings with certain harmonies or keys, for example, a minor key as melancholy, but what we are talking about in Classical music are thoughts that could not be expressed otherwise. Thoughts so deep and eternal that they are outside the customary language culture. They both precede and are higher than what can be obtained in a conversation, putting music closer to the innate ideas of the soul.

‘Songs Without Words’

A more explicit discussion of words versus music in expressing a true idea is taken up by Felix Mendelssohn in composing his “Songs Without Words”—a clear polemic against belittling music to a mere tonal painting of pastoral scenes, or to a mimicry of a sensual poem:

“People often complain that music is ambiguous, that their ideas on the subject always seem so vague, whereas everyone understands words; with me, it is exactly the reverse; not merely with regard to entire sentences, but also as to individual words; these, too, seem to me so ambiguous, so vague, so unintelligible when compared with genuine music, which fills the soul with a thousand things better than words. What the music I love expresses to me, is not thought too indefinite to be put into words, but, on the contrary, too definite…. If you ask me what my idea is, I say—just the song as it stands; and if I have in my mind a definite term or terms with regard to one or more of these songs, I will disclose them to no one, because the words of one person assume a totally different meaning in the mind of another person, because the music of the song alone can awaken the same ideas and the same feelings in one mind as in another—a feeling which is not, however, expressed by the same words.[8] Words have many meanings, and yet music we could both understand correctly. Will you allow this to serve as an answer to your question? At all events, it is the only one I can give—although these too are nothing, after all, but ambiguous words!”[9]

This to me says that there are pure thoughts, musical thoughts, that can’t be translated into words. These are the closest to preconscious thoughts and processes. Felix says that the people who complain about music are not secure in thinking of principles that are above sense-perceptions. They would be grateful to be given a handbook to life that they could follow, as if they were obeying a parking sign.

But would such people be developed enough mentally to understand something as universal as gravity, which cannot be sensed directly, nor be described (in terms of what causes its effects) by equations or a basic definition, and which does not exist as an object, but is most real and powerful? Would someone in this state or with this capacity be able to understand something as ephemeral as love? They would miss the meaning of both these concepts by looking them up in a dictionary, although they could not deny their existence and influence.

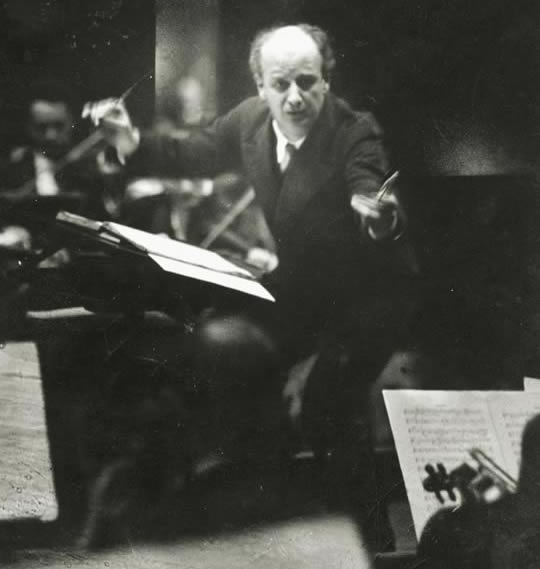

Furtwängler Defends Beethoven

The same Richard Wagner who attacked Mendelssohn as a Jewish musician who corrupted German Romantic music with intellect, criticized Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, by saying that the music does not match the words. Wilhelm Furtwängler, the greatest conductor of the 20th Century, defends Beethoven from “the fallacy which results from attempting to record the idea rationally in words—a task which is, of course, impossible without sacrificing the substance of the idea to a very considerable extent…. Beethoven, more than anyone else, had an urge to express everything in a purely musical form. The musician in him felt inhibited, not inspired by a text: He would not allow the textual form of a word to dictate to him what form his music should take. Thus Beethoven becomes completely himself only when he is free to follow exclusively the inherent demands of music.”[10]

Wilhelm Furtwängler, the greatest conductor of the 20th Century, defended Beethoven from attack by the fasicst composer Richard Wagner: Beethoven, said Furtwängler, “would not allow the textual form of a word to dictate to him what form his music should take.” |

We should recognize Beethoven’s desire to be free from any “textual form of a word,” and to live on the musical thought, as similar to Einstein’s concept of play and unconscious thought. From this we can gather that music is not limited to an expression of imaginative ideas, but is actually man’s creation, enabling him to model the highest, most productive and organic thought processes; to become more conscious of his creativity, and have more power to wield it.

Johannes Kepler discovered that the musical harmony man uses to externalize his creative mind, is also found in shadow form, in the Solar System, the creative expression of God’s mind. Maybe the well-tempered system as we know it today, is best at communicating genuine ideas because it’s both a reflection of, and is bounded by, physical principles and laws, unlike simple words. You could say that Classical music is the closest the “subjective” gets to the “objective.” Human thought and expression, as noted by Einstein, can be stated as the being and becoming. We start with the living absolute, an ideal—say, a discovery—and then try to communicate it by assembling parts which most approach a representation of our idea. In physical science we’re given the shadow first (an observation of experience or some other evidence, the parts or the becoming), and have to work backwards to know the idea which generated it. “Thus it is no longer surprising that Man, aping his Creator, has at last found a method of singing in harmony which was unknown to the ancients, so that he might play, that is to say, the perpetuity of the whole of cosmic time in some brief fraction of an hour, by the artificial concert of several voices, and taste up to a point the satisfaction of God his Maker in His works by a most delightful sense of pleasure felt in this imitator of God, Music”—Kepler’s Harmonice Mundi.

To conclude (if this can be done in words): The true scientific imagination is (at least) non-verbal. In order to free our minds from literal thinking, we have to ask ourselves: Does the way language is currently used bound our thinking? Do we let an internal teleprompter tell us what to think? We understand that language is useful and necessary, for explaining things to others, but is it sufficient? Is it sufficient for true higher thinking? We see with Einstein that the secret to science is to go beyond language. The secret that humanity has developed for thinking about how we think, is Classical music. We use music as a model of pure thought; as a tool for willful creativity, allowing for reflection and improvement of our thinking. This leaves me with the question: Is thinking not only non-verbal, but is it non-visual as well? Is thinking non-sensual entirely?

[1]. http://www.larouchepac.com/node/21237 and http://www.larouche pac.com/metaphor-intermezzo and http://www.larouchepac.com/node/ 21206.

[2]. Wertheimer, “Productive Thinking.”

[3]. Jacques Hadamard, The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field, 1944, Appendix II, “A Testimonial from Professor Einstein.”

[4]. Albert Einstein, Autobiographical Notes, 1946.

[5]. Einstein, “The common element in artistic and scientific experience,” Menschen, February 1921.

[6]. Walter Isaacson, Einstein, His Life and Universe, 2007.

[7]. V.I. Vernadsky, “Thoughts and Sketches: Les musiciens ne font que commencer a connaître la jouissance du sens historique” [Musicians are only beginning to understand the pleasure of the sense of history]; W. Landowska, Musique ancienne, translated by Bill Jones. Vernadsky’s question has been addressed in a blog post on www.larouchepac.com by this author.

[8]. Goethe also says, in the fourth part of “Dichtung und Wahrheit,” “I have already but too plainly seen, that no one person understands another; that no one receives the same impression as another from the very same words.”

[9]. Felix Mendelssohn Bertholdy to Marc-André Souchay, Lübeck. Souchay had asked Mendelssohn the meanings of some of his “Songs Without Words.” Berlin, Oct. 15, 1842. William Empson, author of Seven Types of Ambiguity, would agree, although he considered language a tool, rather than a hindrance to express ideas.

[10]. Wilhelm Furtwängler, “Concerning Music,” 1953. This is not to say that Beethoven was not inspired by poetry, but is only to emphasize that Beethoven is superior to someone like Wagner, because he was not operating on story-lines, what could be called “program music,” or more recently, movie music.