Putin in Japan—A Transformation of Asia

by Michael Billington

January 2017

A [PDF version of this article]appears in the December 30, 2016 issue of Executive Intelligence Review and is re-published here with permission.

Dec. 24—President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Japan on Dec. 15-16, meeting with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe first in Abe’s home prefecture of Yamaguchi, then in Tokyo, has solidified a positive transformation of relations between the two nations taking place over the past year. This process has linked Japan firmly into the development of the Russian Far East, while also demonstrating that Japan is capable of acting independently from the British imperial policies which have dominated Washington over the last 16 years of misrule under George Bush and Barack Obama.

kremlin.ru

Russian President Vladimir Putin (left) welcomes Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to Russia on Dec. 15, 2016, for serious strategic talks. |

This transformation extends beyond the bilateral ties between the two nations, contributing to a general shift of the entirety of Asia away from the divisions created by the Obama policy of encircling China and Russia economically and militarily, which has brought the world to the brink of thermonuclear war. Instead, Asia is increasingly united behind the new paradigm of peaceful development and cooperation, centered on the New Silk Road process set in motion by China and fully supported by Russia.

While the festering territorial issues—which have prevented the signing of a peace treaty between Japan and Russia since World War II—were not settled during the Putin visit, the path to a solution was firmly established. It is based on joint development of the contested Kuril Islands (called the Northern Territories in Japan), and huge Japanese investment and infrastructure development within Russia.

Two Japans

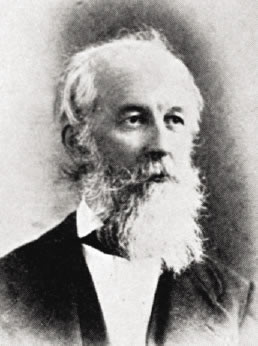

E. Peshine Smith, American System economist, was employed by the Meiji Government 1871-1876. |

Lyndon LaRouche has always insisted that there are two Japans. First, the Japan of the Meiji Restoration, heavily influenced by the American Hamiltonian system, which was introduced to Japan by economist E. Peshine Smith. He served as the first foreign advisor to the Meiji government from 1871-1876. Smith—a friend of American System economist (and Lincoln advisor) Henry Carey—aided in the transformation of Japan from a feudal society to a modern industrial power.

The second Japan emerged under the influence of the British Empire, which convinced some Japanese leaders of the Meiji that, as an island nation like the British, it must become an Empire, militarily colonizing other nations, in order to have access to the raw materials it would need. This faction led to the horrors of World War II, begining with Japan’s military occupation of much of China in the 1930s.

Post-war Japan, under the tutelage of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, returned to being the Japan of peaceful development, rapidly becoming one of the world’s greatest industrial powers, while retaining a constitutional restriction against waging war. The current Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, who served as a post-war Prime Minister from 1957-60, and Shinzo Abe’s father, Shintaro Abe, Foreign Minister from 1982-86, both made efforts to restore relations with Russia, despite the British-American Cold War hysteria against Russia at that time.

|

|

|

|

Nobusuke Kishi (left), the maternal grandfather of Shinzo Abe, was the 56th and 57th Prime Minister of Japan. Shintaro Abe, Shinzo Abe’s father (right) was Japan’s longest reigning postwar foreign minister. Both father and grandfather were committed to developing good relations with Russia. |

||

The primary conflict between Japan and Russia was (and still is) the issue of sovereignty over the Kuril Islands (Northern Territories), the four islands north of Hokkaido in the Kamchatka island chain, which were occupied and claimed by the Soviet Union near the end of World War II. In 1956, Japan and the USSR reached an agreement to divide the islands—two to each side—but U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who served as a spokesman for British imperial interests throughout his life, threatened Japan that if it failed to demand sovereignty over all four islands, the United States would renege on its pledge to return Okinawa to Japanese sovereignty.

After that, the U.S.S.R., and post-U.S.S.R. Russia, refused to renew their offer to divide the islands. A second effort at reaching a similar agreement in 2000 also ended with Japan walking away from the discussions—probably under U.S. pressure.

President Putin clearly understands this problem—that Japan is still an occupied country in some respects, one which has sometimes acted against its own interests due to pressure from Washington. In an interview with Yomiuri Shimbun and Nippon TV in Moscow on Dec. 13, just before his trip, Putin responded to questions about his expectations for reaching an agreement by touching on this reality in his reply:

Look, I have just said we have the highest bilateral turnover and continue liberalizing our trade ties, as you know. However, Japan imposed economic sanctions against us. Do you see the difference? Why? Due to the events in Ukraine or in Syria? However, Japan and Russian-Japanese relations are hardly related to the events in Syria or in Ukraine. Therefore, Japan has some alliance obligations. We treat them with respect, but we need to understand the degree of Japan’s freedom and what steps it is ready to take. We should look into this, as these are not minor issues. Our foundation for signing a peace agreement will depend on them. This is the difference between current Russian-Japanese and, for instance, Russian-Chinese relations. I do not want to argue; you asked me what the point is. The point is to create an atmosphere of trust.

The New Paradigm

Nonetheless, Putin has welcomed Abe’s call for renewing the 1956 framework, indicating that after a period of joint development of the islands, and visits there by former Japanese residents, businessmen, and tourists, the concept of returning two of the islands can again serve as a basis for a final determination and a peace treaty.

kremlin.ru

Putin and Abe emerging from a working session on Dec. 15, 2016. |

The process between these two leaders during 2016 was fascinating. It began with a visit by Abe to meet Putin in Sochi in May. Despite Obama’s insistence that Abe not hold such a meeting, the two leaders met, and expressed a commitment to resolve all outstanding issues and proceed with cooperative development. Japan had imposed minor, token sanctions on Russia under pressure from Obama after the U.S.-orchestrated coup in Ukraine, but Putin essentially ignored that as rather unimportant.

Sources in Japan who are close to both the Japanese and Russian governments told EIR at the time, that the sovereignty issue would only be discussed privately, but that the path to a resolution in 2017 or 2018 would be set in motion as joint development proceeded.

Lyndon LaRouche, in reviewing the eight-point joint Japan-Russia development proposal put forth by Abe in Sochi, asked: “Is Japan really going to do this? If so, that’s a very positive development for the entirety of Asia.”

The proposal for Russia’s Far East included oil and gas development, medical facilities, transportation, port development, and more.

Western Economic Crisis

Soon after the Sochi visit, Japan hosted the annual G-7 Summit—without Russia, since Russia had been thrown out of the former G-8. At that Summit, Abe challenged Obama and the other G-7 leaders by refusing to go along with their fraudulent hype that the western economies were doing fine, that a steady recovery was on the way, and that the insane speculative binge driving the trans-Atlantic financial system to the brink did not exist.

Abe spoiled the party, telling the Summit that there was a severe risk “of falling into a crisis if we did not take appropriate policy responses in a timely manner.” He told the press after the event that “We’re facing a big crisis and big risks.” Yomiuri Shimbun reported that: “The Prime Minister compared the current situation to the one that existed before the global financial crisis triggered by the collapse of Lehman brothers.” Abe called for a concerted fiscal stimulus by the other G-7 nations, pointing precisely to his proposals for the development of the vast Russian Far East, and Japan’s other investments in Asia, as a model.

Obama and the British would hear none of it. Bloomberg gloated that “Japanese Prime Minister Abe failed in his bid to have the G-7 leaders warn of the risk of a global economic crisis in a communiqué issued as their Summit wraps up.” Instead, the communiqué expressed the fantasy that the G-7 countries “have strengthened the resilience of our economies in order to avoid falling into another crisis.”

Abe then travelled to Vladivostok in September to attend the Eastern Economic Forum, at which he focused on the development of the Russian Far East, during another private meeting with Putin. Eighteen development projects in five categories were discussed and presented to the press, which included airports, Advanced Special Economic Zones, Free Port cooperation, joint funds for urban development, joint industrial parks, a Sakhalin-Hokkaido power and transport bridge or tunnel, and cooperation on the development of an Arctic sea route.

Essentially all of these projects were approved during Putin’s December visit to Japan—and more. More than 60 projects and cooperation agreements were signed, totalling about $2.5 billion, and a joint investment fund of $1 billion was established, with plans to launch 20 projects in the first half of 2017.

Beside plans for building a Sakhalin-Hokkaido rail connection, Japan may help build a tunnel connecting Sakhalin to the Russian mainland. Together these two tunnels would link all of Japan to the Trans-Siberian Railroad, and thus to all of Eurasia by rail, thus linking to the new rail routes being built under the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative.

Nuclear cooperation is also on the table, as Russia’s Rosatom State Atomic Energy Corporation signed an agreement for peaceful nuclear power development with Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, including an expansion of Russia’s supply of enriched uranium to Japan.

The joint statement signed by Putin and Abe included the statement: “The start of consultation on joint economic activity of Russia and Japan on the South Kuril Islands may become an important step towards signing a peace treaty.”

kremlin.ru

Putin and Abe at the conclusion of their talks. |

The Governors of Russia’s Sakhalin Region and Japan’s Hokkaido Prefecture met on Dec. 18, and Sakhalin Governor Oleg Kozhemyako said: “We are ready to provide Japanese companies with an opportunity to implement various projects in the South Kuril Islands that would cover housing construction, road-building, setting up waste recycling facilities, and developing aquaculture.”

In an interview with TASS following Putin’s visit, Abe said: “From my Grandfather [Prime Minister Kishi] I learnt that if this is a policy that you believe is right—if this is a conclusion to which you came as a result of thorough considerations—then you need to conduct it decisively and firmly, and sometimes with a danger for life.”

Regarding the agreements with Putin, he added: “I think that it is the Japanese-Russian relations that have the most of all possibilities, and it can be said that these possibilities are unlimited.”

China’s Role

The historic significance of this new relationship for all of Asia, and the world, has been largely ignored in the West, and when it is reported on, it is described as an effort by Japan to work with Russia as a “hedge against the rise of China,” with the claim that both Russia and Japan are worried about the supposed China threat.

In fact, in his interview with Yomiuri Shimbun in Moscow before his trip to Japan, Putin strongly asserted the extremely strong strategic partnership between Russia and China, indicating that such a level of trust was the necessary basis for moving relations between Russia and Japan forward. He noted his deep respect for Japanese culture (emphasizing his love of judo since his childhood), but insisted that he loves Russia more, and must act on the basis of Russia’s fundamental interests.

While the distrust between China and Japan since World War II is far more difficult to overcome than that between Japan and Russia, it is precisely the cooperation among nations on large-scale physical development projects which has formed the basis for China’s Belt and Road Initiative, including an invitation to Japan (and the United States) to participate. China is legitimately concerned about Abe’s effort to drop Japan’s Constitutional restriction against war, allowing Japan to join in foreign wars, such as any potential U.S. war on China. However, Abe has, over the last year, pulled back on his push for such a change—under strong domestic and international opposition—although, for him, it remains a serious concern.

Using the Silk Road concept as the basis for win-win cooperation among nations, we can, and must, replace the imperial concepts of geopolitics, zero-sum competition, and conflict among the world’s nations and peoples. The Russia-Japan agreements provide another dramatic step towards that vision for the future.