Mozart’s Entschlossenheit, or

“Don Giovanni” vs. Venetian Ca-Ca

by David Shavin

December 2010

Occasionally, countries really do dig themselves into a really big financial hole. And some hard-hearted souls attempt to take advantage, by manipulating the consequent sense of panic. Hence, mere hard times are escalated into a cold-blooded pruning of the weaker and more helpless. Those who intend to stand by and observe, label such manipulations as 'unfortunate' or 'unavoidable' or 'unintentional'. Those who intend to stop such practices call them 'fascists'.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, unfinished portrait by Joseph Lange |

Here, we have a happier historical situation to examine: in the immediate wake of the American victory at Yorktown, when the British empire was "turned upside down", every king and queen of Europe in the 1780's had a choice to make - whether their land was best managed by breaking down feudal classes, and developing the fallow talents of their peasant populations; or whether they would actively suppress the 'American' model. Importantly, the imperialist faction led by Venice and London had been caught with their pants down, and it was up to republican leaders to maintain the offensive, using the defeat of the British empire to export 'American' policies back into Europe. Those recalcitrant souls, who, when given a choice for good, still preferred evil, were identified as part of the "Venetian Party", or as 'satanists', etc., but they exhibited the same sado-masochism as today's fascists.

While most might find it credible that Benjamin Franklin may have been carrying out such a battle based out of Paris; and perhaps reasonable that the somewhat unlikely figure of the philosopher, Moses Mendelssohn, might have been the center of such a struggle out of Berlin; it seems rather incredible that the musical genius, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, was actually the political statesman leading the conjoined effort out of Vienna. But his operas were the most precise and targeted political and cultural interventions in that crucial decade, when the Satanists of Venice and London were deployed against his Emperor, Joseph II of Austria - the European head of state who had gone the farthest in attempting to import 'American' reforms into his land. And when it came time for Mozart to throw a punch to the back of the head, or to call a fascist 'a fascist', he rose to the task. Hence, Mozart's 'entschlossenheit'.

"Don Giovanni"

In 1787, Mozart's opera, "Don Giovanni", exposed the behind-the-scenes evil that was bringing down the 'America' faction in Europe. A paid Venetian agent, Giacomo Casanova, beginning in 1785, had one of his prostitutes, Kasper, regularly visiting the Emperor, while another Venetian agent, Cagliostro, co-ordinated the operations in Paris against the Emperor's sister, Marie Antoinette. Mozart's librettist, Lorenzo da Ponte, discovered the Casanova operation, and proposed the 'Don Giovanni' subject to Mozart - that is, proposed putting on stage the peculiar, diseased state of mind of a Casanova, to examine its hellishness on earth and afterwards - but also to examine how this type of evil infects victims and bystanders, regardless of how well-intentioned they may take themselves to be against such evil. Their audience must not simply be horrified at the spectacle of an evil man being dragged down into hell, but must expunge all varieties of equivocation and dissimulation, which they had identified with in the characters on stage - and so become different people. people capable of 'American' revolutions in Europe.

Mozart's Strategic Operas

On two previous occasions, Mozart had crafted such major cultural/strategic interventions on behalf of Joseph II and his 'America project'. First, in Vienna, in 1782, his "Abduction from the Seraglio"1 exploded a Venetian operation to inveigle Joseph II into a useless war against the Turks, and addressed the higher issue: whether human identity was a matter of blood-lines and races, or whether the success of the American Revolution offered European civilization a fresh chance to realize the universal character of the best of Christianity - which also found its cognates within Judaism and Islam.

The Venetian-British concern, after the smashing victory at Yorktown, was to induce courts to fall into old imperial patterns, and thereby turn consideration away from the 'America' option - in a word, to change the subject. The centennial of the much-touted victory in 1683, defending Vienna from the invasion of Turks, was seen by the British and Venice as an excellent focal point for a new mission for Austria. They pressed Joseph II to make the central issue for Austria, a new religious war against the infidel Turks.

Emperor Joseph II of Austria |

About a year before Yorktown, Joseph had become the sole ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Previously, he had shared rule for fifteen years with his mother, Maria Theresa. Now, he had pressed ahead on a series of reforms, predicated upon the possibility of developing a productive middle class. These measures included freeing the serfs, expanding education and civic rights, allowing open discussion in print, promoting mining, agriculture and science, building public hospitals and the like. He promulgated Joseph Sonnenfels' famous "Edict of Toleration"2 - reforms for Protestants and Jews, allowing these non-Catholics to attain equal rights and treatment if they measured up to common civil standards (e.g., the knowledge of German, or the taking of oaths in court). These reforms - announced on the same October 19, 1781 as America's defeat of the British at Yorktown - turned the world upside down on the medievalists controlling the Hapsburg empire. Sonnenfels, the promoter of Moses Mendelssohn's Berlin reforms into Vienna, was aided in this work by Joseph's right-hand man, Valentin Gunther - whose next mission included the co-ordination with Mozart on the opera, "The Abduction from the Seraglio". Importantly, it would be a German language opera, expected to attract the general population into more serious public deliberations than the equivalent of 'punch-and-judy' shows.

In late May, 1782, about three weeks before the premiere, Gunther and Mozart had an extended dinner meeting. The next morning, Gunther was arrested, charged as a 'Prussian' spy. Mozart's opponents, including the head of the secret police, Anton Pergen, saw Gunther and Mozart as operatives of Berlin's Moses Mendelssohn.3 Anything that suggested of reforms that could build up a middle class was deemed by a certain reactionary class as tainted with Jewishness. Fortunately, as a side benefit of the success of Mozart's "Abduction", that is, of the population being won away from a senseless war mania, Gunther would be released before the summer ended. Joseph's reforms were not still-born - and they probably would have had more than a couple of years, if developments in other European capitals in the summer of 1782 had benefited from the quality of Mozart's targeted intervention in Vienna.

"Abduction from the Seraglio"

In the original ending of Bretzner's play, the four Christian captives of the Turkish Pasha Selim are rescued when, at the last moment, the hero, Belmonte, is discovered to be the long-lost son of the pasha. This classic device, a 'deus ex machina', makes for dubious theology and bad drama. In cheating the audience, the public discourse is abused. Mozart altered the ending in a way that shocked and captivated his audiences - Belmonte is discovered to be the son of the Pasha's worst enemy, the one responsible many years ago for the oss of Selim's fiancée! The specific fears of imprisonment and possible death now sky-rocket into unmentionable fears involving retribution, vengeance and torture:

Selim: "It was because of your father, that barbarian, that I was forced to leave my native land. His insatiable greed deprived me of my beloved, whom I cherished more than my own life. He robbed me of honor, property, everything--he destroyed all my happiness.'

Belmonte: "Cool your wrath on me, avenge the wrong done to you by my father. Your anger is justified and I am prepared for anything."

"It must be very natural for your family to do wrong, since you assume that I am the same way. But you deceive yourself. I despise your father far too much ever to behave as he did. Have your freedom, take Constanze, sail home, and tell your father that you were in my power, and that I set you free so that you could tell him it is a far greater pleasure to repay injustice with good deeds than evil with evil."

Belmonte: "My lord, you astonish me."

Pasha (with a look of contempt): "I can believe that. Now go--and if you become at least more humane than your father, my action will be rewarded."

The opera set off storms of controversy. The original librettist attacked Mozart, writing that the principle of the beneficence of good deeds was "more noble, but also, as is invariably the case with such exalted motives, [it was] much more unlikely." Possibly so - but the unlikely had just occurred at Yorktown, and Mozart was not going to look the other way. The unlikely struck a chord with the population, greatly amplifying Joseph's cultural and political possibilities. Mozart's unlikely choice was based in his reading of Gotthold Lessing's (1778) treatment of "Nathan the Wise" - another controversial work in Vienna. (Amongst other things, in Vienna Lessing was accused of being paid by Jews to undermine traditions.) Mozart was lodging at the time in the household of Fanny Arnstein, an avowed advocate of Lessing. Fanny, from the Berlin Itzig family, had the source of Mozart's prized copy of Phaedon, Mendelssohn's treatment of the immortality of the soul - or of the entschlossenheit of Socrates! (Fanny might well have been the source for Mozart's copy of "Nathan the Wise".) Mozart attended readings of Lessing's play at Countess Thun's salon. There Mozart would read selections from his "Abduction" as they were being finished. Attendees at these hearings included Sonnenfels, Prnce Kaunitz (the Chancellor), and even the Emperor on occasion. Venice would not have its Turkish war. or at least it was delayed for six years. Eventually, its disastrous outbreak would also keep Joseph away from Mozart's "Don Giovanni" intervention into Vienna.

"Figaro"

Lorenzo da Ponte was introduced to Mozart in 1783 at Baron Raimund Wetzlar's home. Wetzlar had taken an abiding interest in Mozart, including the provision of free housing for him and his new bride, Constanza. He stood as godfather for their first child, Raimund Mozart. Up until 1782, Wetzlar had shared a box at the theater with Fanny Arnstein's good friend, Eleonore Eskeles. At that point, Eleonore had been arrested by Pergen. As she was the mistress of Gunther, she was supposedly evidence of his spying for the Prussians. However, when he was cleared of the charges, she, the 'Jewess', bore the brunt of the blame for suspicions ever having been cast upon him; and so she was expelled from Vienna permanently. Wetzlar, a converted Jew, introduced da Ponte, also a converted Jew, to Mozart (in what might be termed 'Eleonore's Revenge'!) and Mozart turned to him a year later, when he wanted to set Beaumarchais' "Figaro" as an opera - his second major intervention.

Perhaps the most succinct way to characterize the interest in 1784 for "Figaro" is to compare the situation to the post-Civil War South. Joseph had freed the serfs in 1781, an action that required the aristocratic landowners of Austria and Hungary to take up the challenge of developing their lands, no longer with medieval techniques, but with more educated and skilled labor. Joseph would have to counter the psychological problems at the root of all the backsliding that was consciously and unconsciously sabotaging the reforms. While his nobility had agreed to the reform on paper, in their hearts they still viewed the former serfs as pieces of meat. Beaumarchais' play centers around an enlightened nobleman, Count Almaviva has, on paper, renounced the 'right of the first night' - the medieval right to have sex with any bride in the realm, before she can be with her husband - but he spends the whole opera attempting to carry out what he has renounced. Mozart loved the idea of treating such haughty medievalists' economic backwardness in terms of their unresolved sexual appetites. They would be given a choice between ridicule for their unlawful lust or a celebration of the sustained, lawful passion that Mozart would develop in the opera.

Figaro, The Play

Beaumarchais had written the play in a period (1776-77) when the matter of the inner workings of the nobility was a life and death issue for him. What were the true intentions of the French court? He was the central figure in providing French munitions and supplies to the upstart American revolutionaries, at a time when France had not officially declared a war with Britain or an alliance with the Americans. Was the court simply being opportunistic, using the colonists to make temporary trouble for their rival, Britain, or was the court actually adopting a principled anti-imperial policy against Britain, as well as within France? If Beaumarchais were caught, the government would have to abjure him. He was out on his own, until France finally declared war in the Spring of 1778. Similar to Mozart, Beaumarchais had no trouble figuring out a way to get the underlying issue out on the table.4

Marie Antoinette. |

The play "Figaro" was not publicly performed until April 27, 1784, in Paris - after years of brawls over the matter. (This controversy, along with the successful performance, would have been more than sufficient to bring it to Mozart's attention in 1784; but Mozart also knew of Beaumarchais from his Paris trip of 1778. He had, e.g, composed twelve variations upon "Je suis Lindor" - where Count Almaviva woos Rosine in Beaumarchais' "Barber of Seville.) One could almost delineate the pro- and anti-American factions in Paris from 1782-84 around those who wanted the play produced and those who did not. But first, let it be made clear that Beaumarchais was not simply an author who got caught up in a revolution. First, years before, an early play of his had caught the attention of the Duc de Noailles, a key promoter of Franklin's 1752 electrical experiments and, later, the key proponent of the alliance with America in the French court. (When LaFayette, who had married into the Noailles family, made his 1777 expedition to America, it was taken by the population as a reliable sign that the Noailles were a viable and serious 'America' faction at top policy levels.) In 1767, Beaumarchais wrote back to Noailles about politics and statecraft:

"I have loved it with a passion. Readings, writings, travels, observations, I did everything I could for it. The powers' respective rights, the pretensions of the princes which always upset the mass of mankind, the interaction of governments on one another, those were interests meant for the soul. More than anyone else, perhaps, I have felt crossed by my need to take a large view of things, while I am the least of men. I have sometimes felt like protesting, in my unjust humor, against fate which did not place me in a position more appropriate to what I felt I was suited for. Especially when I considered that the mission given by kings and ministers to their agents certainly do not impress on them, like the ancient apostleship, a sort of grace which would make enlightened and sublime men out of the puniest brains."

Secondly, on April 27, 1775, eight days after the 'short heard round the world' from Lexington and Concord - even though the news would not arrive in Paris for three more weeks - Beaumarchais delivered a study for Louis XVI: "I know.[t]he effect of the troubles of the mother country upon her colonies, and of the latter upon England; what must ensue for both: the extreme importance these events have for the interests of France.". Beamarchais begins working with the secretive "Friends of America". So, by 1781, Beaumarchais is certainly prepared for his fight to win the peace, and "Figaro" is central to that fight.

On September 29, 1781, three weeks before Yorktown, his "Figaro" was given a first reading at the Comedie-Francaise, but the actual staging of the play was then forbidden by a too-cautious Louis XVI. However, his wife became more bold. That winter Marie Antoinette attended a celebration of America at the Hotel de Ville, where her discussion with LaFayette's wife, Adrienne, led to her giving Adrienne a ride home in her carriage. When LaFayette returned a few months later, Marie made sure to dance with him at a ball given for the visit of the Grand Duke Paul of Russia. (On this trip, a reading of "Figaro" is arranged for the Grand Duke.) Even though the Censoring Committee officially prohibited the staging of the play5, the Queen took a central role in promoting "Figaro". It became the fashion to read it in organized gatherings of the nobility throughout 1782 and 1783 - the period of the peace negotiations. With some daring, a performance in Versailles was arranged for June 13, 1783, but as the audience was waiting for the curtain to go up, Louis overruled Marie Antoinette. The show did not go on. Only after the Treaty of Versailles was signed, September 3, 1783, was a staged performance finally allowed about three weeks later - though, even then, the public was not invited. The first public performance must await until April, 1784. Marie had been the most powerful force in France pushing for "Figaro".

It is at this point that the bold initiative is set into motion by Venetian agent Cagliostro to target Marie Antoinette, to paint her in the public eye as the source of the economic woes, woes that were actually embedded in the free trade provisions of the Treaty of Versailles. Instead of investigating the actions of financial speculators upon the supply of French grain, the population was to be provided the image of a luxurious queen, who, when informed that the people were hungry and had no bread, would emit the clueless, "Let them eat cake." This is called the 'Necklace' Affair'. In too-simple terms, a very expensive diamond necklace was to be sold. The buyer would be understood to be Marie Antoinette, but a patsy, Rohan, was to be acting on her behalf. The diamond operation, designed to blow up, would associate Marie in the public's mind with reckless spending, at a time when they would be crying for answers as to the financial looting of France. We'll return to the "Necklace Affair" after following the "Figaro" story in Vienna with Mozart and da Ponte.

Figaro, the Opera

In 1784, Wetzlar encourages Mozart and da Ponte, saying that, if Joseph were not willing to stage "Figaro", he would; and he'd stage it elsewhere if it wasn't allowed in Vienna. This commitment provides Mozart and da Ponte the backup to begin work on the opera, prior to any commission, and despite an order (2/11/1785) issued by Count Pergen that Joseph II will not allow the play to be performed. Then, da Ponte succeeds in organizing Joseph to allow "Figaro", not as a German play, but as an Italian opera. The difference, in part, is that, while the play would have been watched and discussed amongst the general population, the opera would have been directed more narrowly, toward the nobility - and Joseph was very much interested in using the opera to deal with the nobility's reactions against his reforms. In that Spring of 1786, the cleverness and resourcefulness of the servants, Figaro and Susannah; the ridiculous hypocrisy of Count Almaviva, as his hormones control his mind; the blossoming maturity of the Countess, as she summons the courage to name and take action against the loss of love in her life; and the inexpressible power and grace of the finale's dispensation should have been enough to give Vienna and Europe a fresh chance to revive their American reforms.

Mozart had been in a race against the degenerating political situation to get "Figaro" onto the stage. It had largely been composed by November, 1785, but delays were setting in. Michael O'Kelly, the "Don Basilio" of "Figaro", recounted: "Mozart was as touchy as gunpowder, and swore he would put the score of his opera into the fire, if it was not produced first; his claim was backed by a strong party. The mighty contest [against Antonio Salieri and Giambattista Casti6] was put an end to by His Majesty issuing a mandate for Mozart's 'Nozze di Figaro,' to be instantly put into rehearsal."7 So, as late as the Spring of 1786, Joseph was willing to fight for Mozart. Count Orsini-Rosenberg8, Minister of State (and with authority over the Imperial Theatre), then attempted a last silly obstruction. He banned the dance music that was part of a wedding celebration on stage, invoking Joseph's rule against extraneous dance scenes in operas. Da Ponte defeated Rosenberg, by arranging for Joseph to witness the result of Rosenberg's intrusion. Joseph countermanded Rosenberg, and the full opera "Figaro" premiered May 1, 1786. It was a major success in Vienna, and, shortly after, a wild success in Prague.

However, years of retreat and defensiveness had caught up with Joseph. The economic moves can't produce results fast enough to satisfy the as-yet unbroken control of Venetian and London usury. In 1786, the savings-and-loans institution (the 'Bruderschaften') is broken; the re-introduction of the death penalty provides for debased public executions; the Necklace Affair, targeting Joseph's sister, Marie Antoinette, has dominated headlines in France for months; and there is a renewed push from Russia for war with the Turks. For some reason, Count Pergen's Ministry is elevated to a status of 'first-among-equals' with the other ministries.9 No other ministry can know or question Pergen's domain. He reports to no one but the Emperor now, and he prefers not to commit such reports to paper. Further, he seems to wield undue influence with Joseph. For example, not long after Kieve, in 1782, was caught manufacturing the case against Gunther and Eskeles by forging a letter from a non-existent Prussian, he was arrested for selling phony bills of exchange. At that point, from prison, this shady low-level operative was able to demand and receive a private session with the Emperor; whereupon he was freed, and provided an imperial concession for a tobacco monopoly in Galicia. Joseph even arranged to pay off, from his own personal funds, the victims of Kieve's scam! Now, in 1786, several weeks before the premiere of "Figaro", da Ponte confronts Casanova's top whore in Vienna, demanding that they close down their operations, including one young woman, Kasper, who has been attending the Emperor for the last year. This story will be picked up when we get to the "Don Giovanni" opera, but first the background on attack on France, where that other Venetian agent, Cagliostro, ran the "Necklace Affair".

Casanova Does France

Part of Casanova's "catalog" of his conquests. |

The 1770 marriage of Vienna's Marie Antoinette to Louis XVI was meant to be the cement in the historic alliance of France and Austria of 1755/6. Venice had spent a couple of centuries manipulating those two Catholic powers against each other, and Venice and Britain would launch war - the Seven Years War (1756-1763) - over the matter. In fact, a younger Casanova's first major assignment was to punish France by exploiting France's wartime difficulties and lowered credit rating, to manipulate their finances. First, in 1757, though new to France, Casanova was appointed the director of a lottery, set up to 'help' Duverney's Ecole Militaire, as they could not get proper funding during the war.10 Casanova's initial wealth was derived from running this lottery. By 1759, Casanova is put in charge of a much bigger game. He is sent to Amsterdam to arrange for the sales of downgraded French bonds, and the purchasing of national securities with better credit ratings, to 'help' France get around the damage to their credit during the war. His stock in trade was to sell his personality, ply victims with sexual intrigues, chat up his powers of alchemic creation of precious metals, and perform his cabalistic 'pyramid' - where letters could be assigned numeric values, so that contrived results (predictions and advice) could be obtained by his ability to push sums and products where he needed to get them. The numerical result would be converted back into letters, to amaze the victim with the mysteriously-derived message.

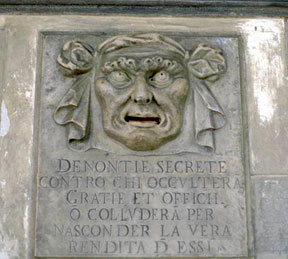

Mouth of the Lion in Venice, where Venetians are encouraged to submit written accusations. |

Though Casanova drops names in his Memoirs that shouldn't be automatically relied upon, it is likely the case that he was indeed working with the Amsterdam banker, Thomas Hope, and the mysterious scam-artist, Saint-Germain. In 1760, the duc de Choiseul moved against Saint-Germain11 - who was tipped off by his Amsterdam contacts and provided with an escape to London. At that time, Choiseul also put an end to Casanova's operations 'on behalf of' the French court. Prior to his two-plus years in high finance, Casanova was just another Venetian degenerate. Now, cut loose, it appears that all controls just came off. Casanova, in short order, spent the rest of 1760 on the road - deflowering a 13-year-old12, visiting Voltaire13 for four days in Switzerland, securing an abortion for a nun at a gambling resort, overdosing another nun with opium (causing her death), meeting with Pope Clement XIII in Rome, and romancing his own daughter, Leonilda14, in Naples - in that order. The stage "Don Giovanni" would be hard-pressed to match such a performance. Of note, the Pope awarded Casanova with the Golden Spur, making him a Chevalier. as in Giovanni, the cavalieri. Quite a year! But, let us leave Casanova to himself for now, and perhaps wash our face and hands.

Casanova's tumultuous career had two main assignments for Venice - dismantle both France and Austria, as punishment for their daring to cross Venice and London. Another part-time student of Saint-Germain, one Joseph Balsamo, aka Cagliostro, was sent into France in 1780 as part of this mission. He made for Strasburg and the castle of Louis, Cardinal of Strasburg, longtime opponent of the French-Austrian alliance. He would soon be promoted for the biggest project of his career, as the developments of 1781 in America and France caught the British and Venice somewhat off-guard.

France Wins the War, Loses the Peace

In mid-January, 1781, in her eleventh year of marriage, Marie Antoinette finally conceived a male heir, solidifying her position at the French court. About the exact same time, January 15, 1781, to be precise, and under strong encouragement from Marie, Louis XVI fired Jacques Necker, the director of finances, whose financial genius involved ruining France with usurious loans from speculators.15 The looming bankruptcy endangered both France and the war effort. But the decision by the French government was a decision to put aside such narrow financial constraints, and to commit their full resources for a possible knockout of the British Empire - what would be known as the 'Yorktown' campaign. It required France to deploy for the first time the required naval forces to rule the Eastern seaboard, providing Washington and LaFayette the opportunity to bottle up the British land forces at Yorktown. Nine months later, Cornwallis surrendered on October 19th - and Louis Joseph was born on October 22nd.16

As such, after Yorktown, this same French court should have been capable of employing the same level of entschlossenheit to the task of mobilizing their economy to secure their victory. But by 1783, the French ended up with a treaty that would effectively leave London speculators in charge of their economy. (The full 'free trade' arrangements between England and France were not secured until the Eden Treaty of 1786.) How was this possible?

During the protracted peace negotiations, a key destabilization of the French court occurred in September, 1782, when the Guéménée's bankruptcy was triggered - a direct shot over the head of Louis and Marie. The Duchesse de Guéménée was the titular governess of Marie's son, the long-awaited Dauphin. The astounding one-million-pound bankruptcy of her husband threatened a chain reaction throughout France.17 Marie Antoinette promised the Duchesse that the King would impose a moratorium upon any collection attempts, and so cut off any chain reaction. But the Treasury did not deliver, and it was the Duchesse's brother, Louis de Rohan, Cardinal of Strasburg, who assumed the major share of the attempt to plug the financial hole.18 It was immediately after this bankruptcy that the British sued for peace, and the French negotiations with the British, in October and November, 1782, seems to have gone drastically soft.19 The British succeeded in splitting up the allies, and France agreed that 'free trade' was going to be good for them. Indeed, France had won the war, and lost the negotiations.

From 1781-83, great pressure was exerted upon the King - to which he unfortunately submitted - to prevent the mobilization of the court, and of the population, around Beaumarchais' "Figaro" play. Marie Antoinette would not win a public performance for this until April, 1784 - at which point Cagliostro would steer his dupe, Rohan, against the Queen, in what is known as the "Necklace Affair." It was primarily a 'mis-direction' operation to steer the population away from an examination of Necker's bankruptcy of France and of the grain cartels' destruction of France, and toward a populist rage at the supposed wastefulness of their 'Austrian' queen, Marie Antoinette. The operation had two importantly different levels: on the tactical level of running a major scam, the thieves around Jeanne de La Motte; and, on the more strategic level, the plotters against the nation of France - involving British intelligence, Swiss bankers, and their agent, Cagliostro. The scam ran from December, 1784 to August, 1785. The ruinous trial by Parlement occurred in May, 1786.

Enter Cagliostro

Count Cagliostro, Knight of Malta . |

Between 1780 and 1783, Cagliostro lived in Strasburg, in the castle of his intimate friend, Rohan. Later, Rohan would keep in his study a bust of Cagliostro, made by Houdon. Rohan was now the Cardinal of Strasburg. Giuseppe Balsamo, now Cagliostro, established himself as a 'man of the people' by curing the poor and providing medicines for free, and paying the debts of the imprisoned poor.20 That he would stay in Strasburg with Rohan for almost three years - evidently the second longest stay anywhere of his adult life - suggests that it must have been considered a major deployment.

Cardinal Rohan. |

Cagliostro reportedly gained the interest of Rohan by means of a 'prediction' of the death of Empress Maria Theresa - which occurred in November, 178021. Earlier, in 1772-74, Rohan had a political mission in Vienna to undermine the union of Austria and France.22 Maria Theresa had viewed Rohan as a factional opponent, and as morally salacious. She would later write her ambassador, Mercy, about Rohan: "He is a very poor subject without talents, prudence or morals; he upholds very badly the character of Minister and of ecclesiastic." Evidently, he was given to parading about the outskirts of Vienna with young women dressed up in drag as abbots.23 Maria Theresa requested that he be withdrawn from diplomatic duties in Vienna. During her lifetime, he would have to suffer a very constricted political usefulness - so Cagliostro's prediction of her death fed Rohan's deeply-held obsession of wielding power at the French court.

Further, Maria Theresa had instruceted her daughter to never trust Rohan. In February, 1777, e.g., Marie Antoinette wrote her mother that Rohan's powerful family had forced the King to appoint him as the next Grand Almoner of France: "I am really annoyed by this, and it will be much against his own inclination that the King will appoint him. If [Rohan] behaves as he always did, we will have many intrigues." Maria Theresa responds that Rohan "has done much harm here." in Vienna.

In June, 1782, Rohan bribed a guard and snuck into Marie Antoinette's private reception for the Grand Duke Paul of Russia - an action that only further angered the Queen against Rohan. (If Cagliostro had not directly impelled Rohan to this action, he would have at least noted Rohan's erratic behavior.) In Rohan's Strasburg, Cagliostro enhanced his fame by curing the gangrene of the Commandant of Strasburg, the Marquis de Lasalle; and, then, in Paris, by restoring the health of Rohan's cousin, the powerful Prince de Soubise. Rohan had Cagliostro live and work in his own castle during this period, and took a deep interest in Cagliostro's alchemy projects. It is also reported that Cagliostro was a delegate at the infamous July, 1782 conference at Wilhelmsbad - an ingathering of all the 'SDS'-type of masons, that had done nothing and risked nothing for the American Revolution, but now would be redeployed as 'revolutionaries' for the post-Yorktown world, against the courts of Europe. Cagliostro would have been the Strasburg delegate, ostensibly on behalf of Rohan.

Cagliostro and Lavater

Caspar Lavater of Zurich came to visit Cagliostro during this period in Strasburg. Of no little importance, Lavater was a major promoter of his fellow Swiss millenialist and religious enthusiast, the now-dismissed Jacques Necker. Lavater, the main instrument in the attack upon Moses Mendelssohn and his Phaedon back in 1769-1770, had now established a pseudo-science, phrenology, the cultish study of mind and character as expressed by the bumps on the skull and the bone structure of the face.24 Lavater was just then involved in an incredibly nasty attack against Mendelssohn's recently-deceased collaborator, Lessing, branding him an atheist. In March, 178225, Lavater's intimate friend (and Necker's fellow Zurich fundamentalist), Pastor J K Pfenninger, with Lavater's sponsorship, began publishing "The Churchly Messenger for the Friends of Religion in all Churches". Its first issue had "extracts from some very trustworthy letters from Brunswick concerning Lessing's death..." - letters that alleged Lessing's atheism, his grief over the writing of "Nathan the Wise," and his blasphemies uttered on his deathbed. Rank ugliness. Lessing's friend, Nicolai, published an article in his "Allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek," asking: "What could have motivated, what could have justified Messrs. Lavater and Pfenninger to do a thing like this?" For the next three years, Pfenninger would keep silent and Lavater would disclaim any responsibility.

However, Lavater and Cagliostro actually had their own prior history. For most of a decade, they had collaborated on the mental and emotional manipulation of Elisa von der Recke, the sister of Courland's princess. Elisa was in distress over her child who had died. Lavater played the role of a father confessor, while Cagliostro would contact the spirit of the dead child. For several years, she was a walking example of a hypocritical Christianity wedded to the wild pagan practices of Cagliostro. By her own description, around 1784, the humanity and agape of Lessing's "Nathan the Wise" helped her regain her moorings, and freed her from the twisted emotional controls of the Lavater/Cagliostro duo. (It is certainly possible that Lavater's hypocritical attack upon Lessing's work provoked her curiosoity.) In the fall and winter of 1785, she visited Mendelssohn and Nicolai in Berlin. Her companion, Sophie, wrote of their visit: "Mendelssohn and Nicolai, who have an intimate knowledge of Lessing's mind and principles, consider [Jacobi's attacks upon Lessing]. a plot by Lavater's party. Jacobi's treatise, which is so eager to base everything, again, upon mere faith [prompted Mendelssohn.] to point out that the first Church Fathers recommended reason as a means of examining Christianity. whereas the more recent theologians degraded the reasonableness of Christianity by disregarding it entirely. Fanaticism (Schwaermerei) and superstition exist among us to a most abhorrent degree."26 Elisa's discussions resulted in Nicolai's manuscript, where he cited Cagliostro as the epitome of a Jesuit operation, not substantially different from Lavater's fundamentalism. Nicolai's study did not get published until 1787.27

Necklace Affair: The Origins of the Plot

However, in Strasburg, Lavater and Cagliostro could just as well have been strategizing over the mental and emotional weaknesses of a new victim, the Cardinal de Rohan. The Yorktown victory had come over the dead financial body of Necker. Perhaps Lavater and Cagliostro would join Necker in never wanting his cooking of the financial records of France to come to light. Instead, a court scandal of Marie Antoinette would misdirect the financial failings of France away from Necker's crowd. If so, this would suggest that a common power behind Cagliostro, Lavater and Necker might be 'triangulated' as the likely source for the Necklace Affair. Cagliostro knew of Rohan's estrangement from power, due to the antipathy of Maria Theresa and her daughter, Marie Antoinette; and knew of Rohan's thankless role in helping the royal couple by picking up his sister and brother-in-law, the Guéménées, off the floor from their 1782 bankruptcy. He also knew of the Cardinal's mistress, Jeanne de La Motte, and her ability to inveigle him in various minor schemes, trading her sexual favors for his help in covering her debts.28 Finally, he would have known that Jeanne had her own particular history: she had just finished serving time in the Bastille in 1782 for having "made dupes by using the name of the Queen on behalf of whom she pretended to be acting," and for using the Queen's seal. The question is: How could Rohan not have known this, or figured it out along the way? It strongly suggests that Rohan had deep fantasies and, perhaps, about Marie Antoinette, that Cagliostro had a precise mental map of Rohan's psychological profile, and that Jeanne had, in fact, been selected to be Rohan's mistress by people with potential frauds against Marie Antoinette on the agenda.

In March, 1784, the game is set afoot. Jeanne lies to Rohan that she is now in the trust of Marie Antoinette. (Evidently, more than once, she would feint near sequestered sections of Versailles, in the hopes of being carried into the private areas.) She obtains funds from Rohan no longer for sexual favors, but as 'contributions' to the favorite charities of the Queen. By May, she has shown to Rohan impassioned (and forged) letters from the Queen, whereby Marie expresses her readiness to grant Rohan "her good-will" - since he had spent the last two years dealing with the Guéménée bankruptcy. For the remainder of 1784, Rohan steps up his contributions in expectation of rehabilitation at the Court. Though Cagliostro had left Strasburg in 178329, he departed with the Cardinal's secretary in tow, and was in written communication with Strasburg. Jeanne never would have been promoted from simply hitting up the Cardinal for money, to the riskier scam of inveigling Marie Antoinette, without Cagliostro's go-ahead; and he re-appeared on the scene in the winter of 1784/5, when the escalation occurred.

Why Target Marie Antoinette?

The prime reason has to be her lead role in promoting "Figaro", as the targeted cultural fight to revive the French court's entschlosenheit of 1781. However, there was an important, secondary factor motivating the attack, which involved the need to diminish her voice at the French court. Her brother, Joseph II was pushing France for a policy to be imposed upon the defeated British, that included as a key component the revival of the port of Antwerp. It had been closed in the 17th century to favor Amsterdam, when the Venetian operations migrated northward to London and Holland, and they consolidated their naval and financial empires. The letters between Marie and Joseph display her role in attempting to persuade Louis XVI for a joint French-Austrian position on this in the peace negotiations. Freeing Europe from the financial and naval control of London was an obvious move. However, British victories in 1782 (e.g., Gibraltar) and the collapsed position of the French court after the September, 1782 Guéménée bankruptcy, left the French court acting more defensively. Joseph II is told that there will be no answer on the Antwerp policy until after the Treaty - that is, the Treaty will not address such matters. But in 1784, he is still awaiting an answer. The way the feudal, crypto-Catholic, Hilaire Belloc, described the situation in 1783 Paris was: "This purely Austrian move [to include the opening of Antwerp against the British.] was the political motive of the whole year, and side by side with it, like a tiny instrument accompanying a loud orchestra, went the rising popular demand for Beaumarchais' play.".

And Why Target Marie Antoinette with the Necklace?

From the age of fourteen until twenty-two, Marie Antoinette was the model of the frivolous waste-thrift. Now, seven years later, when she is twenty-nine and has been close to the center of intense fighting for France's future, this image is thrown back at her. Throughout most of the 1770's, the young Marie Antoinette had an addiction for gambling large sums and spending large sums amongst her close circle at Court. She spared little or no expense on her wardrobe, including expensive jewelry. Her 1770 marriage was the main visible link of the historic French and Austrian alliance of 175630, but by 1777, she still had borne no prince or princess. Evidently, it was not until her brother, Joseph II, came to visit (April - June, 1777) and to explain certain private matters to Louis XVI - which also led to a circumcision operation - that the couple could have a chance for conception.

Marie Antoinette's letters to her mother, Empress Maria Theresa, reflect both her frustrations before, and her happiness after the pregnancy. With this situation resolved, Marie Antoinette's early years of gambling and frivolity also receded.31 Her growth might not have been as singular as the American Revolution itself, but it did run parallel to it. However, that profile of her early weaknesses, and such related gossip, was the basis of the later targeting of her, in particular, with the use of jewelry in the Necklace Affair.

In Spring, 1784, Jeanne de la Motte began delivering letters forged by her husband's accomplice, Retaux de Villete, to assure Rohan that his contributions to Marie Antoinette's charities are winning him favor with the Queen. From afar, Cagliostro's consultations assure Rohan that "glory would come to him from a correspondence" with the Queen, and that "full power with the Government" was imminent. Rohan proceeds with the contributions. Then, Jeanne and her husband raise the stakes by arranging a meeting between Rohan and the 'Queen'. On the early evening of July 24, 1784, Rohan gets to meet briefly in the Venus Grove park with a "Marie Antoinette," who gives Rohan a letter and a rose. She tells him that he will "know my meaning". Just at that moment, a messenger interrupts to tell "Marie" that she must leave unexpectedly and immediately. Jeanne's husband played the role of the messenger. He also had hired a woman of low repute (with the professional name of d'Oliva) for the impersonation. Rohan is ever more deeply caught up in the fantasy. In August, Jeanne gives Rohan a "Marie" letter requesting 60,000 livres to help a family in distress, which sends Rohan to the banker Cerfbeer for a loan. Between August and November, Jeanne obtains what amounts to 6-7,000 pounds for such charitable efforts; but only in December, do they escalate to the infamous 1,600,000-livre necklace and a whole, different ballgame. With the escalation to the involvement of this particular necklace, there was no way that this could remain merely a monetary scam of Cardinal with more money than sense.

The Necklace

Boehmer and Bassange were jewelers for the Court, and they had provided jewelryfor Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette over the years. However, this massive necklace had been unsellable for years, and it was bankrupting the jewelers. (It may well have been a relic from the 1770's, as the first major piece of jewelry turned down by Marie; or it may have been crafted later, in a deliberate attempt to seduce her back into old habits.) They already had been forced to hand over a one-half share of the necklace to their main creditor, Charles Baudard de Saint-James, owner of an estate at Neuilly. Over the years, the French Court had rejected several overtures to purchase the necklace. (Reportedly, once, with regard to some expensive piece of jewelry, Marie Antoinette explained that "the money would be much better employed in building a man-of-war.") By 1784, Saint-James and his jewelers were left with an albatross around their neck. According to the Queen's attendant, Madame Campan, Saint-James was not above palace intrigues on the matter. She related later that "the Queen told me M. de Saint-James, a rich financier, had apprised her that Boehmer was still intent upon the sale of his necklace, and that she ought, for her own satisfaction, to endeavor to learn what the man had done with it."

Jeanne made the proposal to Rohan in late December, 1784, that he act as the front in the purchase of the necklace, on behalf of Marie Antoinette. Naturally, she assured Rohan than the Queen desired the necklace, though she had to arrange finances for it privately and over time. Jeanne met (1/21/1785) with Boehmer's son-in-law, Bassenge - a meeting set up by Louis-Francois Achet, an "Honorary Officer of the Wardrobe of Monsieur," and his son-in-law, Jean-Baptiste de Laporte, a parlement barrister. (They were to get a thousand louis as a commission.) Three days later, Rohan identifies himself to the jewelers as the go-between for the Queen. The deal is set (1/29/1785) at Rohan's Paris address, the rue Vieille du Temple: 1.6 million livres, paid in four installments at six-month intervals, to begin on August 1, 1785. The necklace was delivered (2/1/1785) to Rohan, and he brings it forthwith to Jeanne's Versailles apartment that same day. He witnesses that the courier from the Queen is the same one that he had seen the previous summer (who had interrupted the assignation with the Queen in the Venus Grove) - that is, Jeanne's actual husband, the Comte de La Motte.

Cagliostro's Role

When Cagliostro left Strasburg, around June 1783, he traveled first to Naples to see an old companion from Malta, the Chevalier d'Aquino. Interestingly, Rohan's secretary, Ramon de Carbonnieres, went with him, indicating that both Rohan and Cagliostro meant to stay in close touch during the approximately eighteen months Cagliostro was traveling. By no later than early 1784, he was in Bordeaux with the Comte de Saint-Martin (and then in Lyons with the Duc de Crillon and the Marshal de Mouchy). That spring, in co-ordination with Rohan's mistress, he advised Rohan by letter to proceed with an offensive on Marie Antoinette. Then, late in 1784, Rohan supposedly requests Cagliostro, in Lyons, to meet him in Paris - this at the time that Rohan is contributing heavily for the Queen's 'charities', and just prior to the December escalation to the necklace itself. Clearly Rohan feels the need of Cagliostro's personal counsel. That letter would have signaled Cagliostro that the time was ripe to escalate with the necklace.

Of note, in November, 1784, an extended assembly of the General Convention of Universal Masonry convened, supposedly organized by an "Order of Philalethes." An invitation is extended to Saint-Martin, Cagliostro's host in Bordeaux.32 Later, at trial, Cagliostro claimed that he arrived in Paris on January 30, 1785 - one day after the deal for the necklace is sealed. Regardless, first, his pigeon, Rohan, never would have proceeded without Cagliostro's key advice; and, second, for Cagliostro's date to be true, he would have had both to delay responding to Rohan's request to come to Paris, and to ignore any request from his friend, Saint-Martin, to attend the "Universal Masonry" proceedings in Paris. It suggests that Cagliostro invented the date precisely because it was one day after the necklace deal was sealed. Regardless, even accepting Casanova's testimony, he was there on site with Rohan as the only one capable of managing the pigeon - certainly beyond the level of the mistress and her fellow thieves - for the rest of the show, which would be the next six months.

On February 15, 1785, Retaux offers the necklace diamonds, now broken up into three lots, to two Jewish merchants of the rue Neuve Saint-Eustache, Israel Vidal and Moise Adam. However, the merchants alert the Montmartre police inspector, who in turn, consults the "counselor of the King, inspector of police", Jean-Francois de Bruguieres. The next day, they question Retaux. Evidently, he implicates "la Comtesse de Valois", that is, Jeanne - and, at this point, Bruguieres' investigation halts. Either, the inspector of police, knowing that Jeanne was the mistress of Rohan, decided that he would not take on Rohan and his powerful cousins, or Bruguieres was also on the inside of an operation designed to catch more than stolen jewels. La Motte is free to go to London in April, where he employs the jewelers Gray, Jefferyes as a 'check-cashing' service. He takes a loss, exchanging the diamonds for other stones - which he then is able to convert into cash. (On April 23rd, Nathaniel Jefferyes registers an inquiry with the "public office at Bond Street" regarding any major jewel thefts in Paris.) Then, in June, La Motte is in Geneva, handing over significant sums of monies to the banker, Jean Frederic Perregaux.33

The Trap Comes Down Upon Rohan

Five months have come and gone, and Rohan is still not getting any favorable treatment from the court. The deadline for the first installment, August 1st, draws nigh. He composed a note for Boehmer to send to Marie Antoinette as an acknowledgement of the necklace. The note is handed to the Queen on July 12th, as she comes out of mass. (Later, Campan reported that the Queen thought it was a crazy note, and promptly burned it.) On July 31st, the day before the first installment was due, Rohan received another "Marie Antoinette" forgery from Jeanne, telling him that the money won't be paid for another sixty days. The desperate Rohan gives Boehmer one thousand pounds, simply to purchase another sixty days of time. But everything blows up over the next two weeks.

Between July 31st and August 3rd, it appears that the decision was made to trigger the confrontation with the Queen. On August 3rd, Jeanne tells Bassenge of the forgery, saying that Rohan can be made to cough up the money.34 The next day, Bassenge confronts Rohan. He responds: "If I told you that I had dealt directly with the Queen, would you be satisfied?" Bassenge answers, "My mind would be set entirely at rest." Rohan concludes: "Well, I am as certain as if I had done so, and I will raise my right hand and tell you so upon oath. Go reassure your associate." Instead, for the next five days, Boehmer and Bassenge attempt to "throw ourselves at Her Majesty's feet and uncover our position to her," but they have no audience with her until August 9th at her Trianon. That same day, it turns out, she was actually rehearsing the part of "Rosine" from Beaumarchais' "Barber of Seville" - which she'd present on August 19th. She responds by instructing Boehmer to write a memo on the matter for the head of the King's household, Baron de Breteuil.35 On the 14th, she spends that Sunday with the King, and they decide, contrary to the advice of Vergennes, to have a public trial. Vergennes wishes to resolve the matter privately. Louis tells Vergennes: "The name of the Queen is precious to me; it has been compromised, I must leave nothing undone." And so, the King is undone.

The next day, King Louis XVI calls in Rohan, who admits that Boehmer's memo is accurate. He cannot explain his actions. The King makes him commit a response to paper. Rohan finally admits that his mistress, Jeanne de La Motte, had hustled him. Rohan is arrested and his house put under seal; however Rohan's servant beat Breteuil to the house and secured Rohan's "Marie Antoinette" file. Jeanne fled Paris for her hometown, using the services of an occasional lover, Jacques-Claude Beugnot. When he asked about the wild necklace affair, she told him: "It's Cagliostro from start to finish." Jeanne, Cagliostro, and a couple of minor players (Maitre Blondel and Nicole Leguay) were soon arrested. The Comte de la Motte, who had miraculously avoided capture in France and London on three separate occasions, was arrested in Geneva.

And Upon the King

King Louis XVI . |

The King allowed Rohan his choice, whether or not to have his trial before the Parlement - where Rohan's family connections could ensure a favorable result for him. On September 5th, the King signed the letters patent to transfer the case to Parlement, saying that he was "filled with the most just indignation on seeing the means which, by the confession of his Eminence the Cardinal, had been employed in order to inculpate his most dear spouse and companion." The King's willingness to have this manner of honor played out in front of the Parliament was probably not his best decision. The French ambassador to Rome, the Cardinal de Bernis, had tried to effect a quiet settling of the matter; and, evidently, the Pope was agreeable to having the matter handled quietly in Rome. However, the Cardinal's powerful relatives, the families of Guéménée, Soubise and Conde pushed for a legal judgment, and exerted significant control over the Parlement's eventual decision. Parlement's trial took place on May 30-31, 1786, four weeks after the premiere of "Figaro" in Vienna. Rohan admitted that he had been ensnared because he was anxious to curry favor with the Queen. He is barely acquitted by a vote of 26-23. Everyone else is found guilty. except for Cagliostro, who is cleared of all charges and made into a hero. Jeanne is ordered flogged, branded and imprisoned at Salpetiere.

Cagliostro had made a mockery of the trial. His exotic stories of his past, and his claim that his moneys came from "a mysterious inheritance," all simply played to the crowd. In the two-week period before the trial, he sold 17,000 copies of his self-advertisement! He had admitted that he was an intimate advisor to Rohan, but that he had urged Rohan to throw himself upon the King's mercy and relate what had happened - which might well have been his last advice to Rohan. (At some point in the trial, Jeanne had thrown a candlestick at Cagliostro. Perhaps it was on this occasion.) Upon his acquittal, Cagliostro described his heroic leaving of the Bastille cell: "The night was dark, the district where I lived a deserted one. What was my surprise, when I heard my name being cried out by eight or ten thousand persons!" He feints - did Jeanne tutor him in this art, or vice versa? - which only raises the pitch of the crowd. Then, he announces his recovery: "I am reborn." The crowd is his. Belatedly, the King has him exiled to England. It is at this point that Cagliostro made his famous 'prediction' about the destruction of the Bastille and the fall of the royal house.

The Money Trail

The creditor of the jewelers, and half-owner of the necklace, was Charles Baudard de Saint-James36. He evidently had lost massively during the 1782 Guéménée bankruptcy, and may have had a grudge against Rohan. However, he had his own problems. A French advocate of the British free trade policy, he actually Anglified his own name. As tax manager of the Navy, he was more interested in cheating the public Treasury - for which he was finally arrested in 1787. However, above Saint-James was the Genevan banker, Jean Frederic Perregaux, to whom the Comte de La Motte handed over the proceeds from the sale of the diamonds. But probably above both was the Genevan financier, Isaac Panchaud, who held British nationality and conducted money manipulations in London and Amsterdam. (He is a leading candidate for the overseer of the usurious loans to Rohan as early as his 1772-74 escapades in Vienna.) This millenialist was key to the 1786 Eden Treaty that consolidated the free trade arrangement upon France.37 Otherwise, at the trial, Cagliostro refused to disclose his financial sources, except for naming banker Jacob Sarasin of Basle, an intimate of Lavater, along with an otherwise unidentified "Sancostar" of Lyon.38 While they might well have been players in the operation, it is unlikely that Cagliostro was going to give names on the level of Panchaud or above.

Of note, Panchaud, in this same period (1785), attempted to crush Beaumarchais' water company. Beaumarchais had arranged for public stock for the first system of pumped water for Paris. Along with fellow speculator Clavieres, Panchaud attempted to drive the stock prices down, betting that the anti-progress crowd could disrupt the project - not the first or last time greenies would be part of financial shakedowns. When Beaumarchais out-organized them, winning public support, they brought in a hired pen39, Mirabeau, to polemicize against the project. Here we have a clue as to Panchaud's circles, as Mirabeau had just returned from London, where he was working for William Pitt. Mirabeau's first assignment in Paris was the blackmailing and double-timing of Calonne, the finance minister, the opponent of Necker and proponent of Beaumarchais40. Beaumarchais wrote a very effective counter-attack, which he could not refrain from entitling "Mirabelle"! Mirabelle's next job was to go to Berlin, just after Mendelssohn's death, and, pretending to admire Mendelssohn, infiltrate his circles. In particular, Mirabeau's backers had a problem with Nicolai's exposé of Lavater and Cagliostro, so Mirabeau composed his own version. It was his 'exposé' of Lavater and Cagliostro, not Nicolai's, which was distributed outside Cagliostro's trial in Paris that May!

Louis XVI as Ottavio

Cagliostro obtained political refuge in London.41 From London, the leading attempt to expose Cagliostro was run by Beaumarchais' associate, Charles Theveneau de Morande, the editor of the "Courrier de l'Europe". (In 1784, early in the Necklace Affair, Morande's "Anglo-French Gazette"42 had been requested by French authorities to expose Cagliostro's operations.) Morande exposed Cagliostro's true identity as one Giuseppe Balsamo of Palermo. Cagliostro had invented an exotic past, beginning as orphan left in Malta, and had sworn in court that he was not this 'Giuseppe Balsamo'. (There is some delightful evidence that Mozart enjoyed hearing of Cagliostro's pedestrian origin. In Zerlina's aria "Vedrai carino", he changed da Ponte's text from "antidoto" to "balsamo"43 - significant, even if only an inside joke.)44 Now Cagliostro proceeded to challenge Morande, in the (September 5, 1786) "Public Advertiser", to a contest of eating a pig laced with arsenic, where the survivor is proven correct. Morande doesn't take the pig bait - that is, he doesn't bite.45

From the ridiculous to the tragic. The Necklace Affair worked in part because of Rohan's fantasies, but primarily because the King had failed to recognize the Venetian evil. Instead, he reacted to a perceived affront to his wife's honor, thinking that a guilty verdict would clear his wife's name. However, any such public attention, reviving the image of the immature Marie Antoinette, was deadly in a world where free trade agreements and grain speculators were descending upon France. The decision to murder the sovereign nation of France had been made. That is what it means to be playing gambling games with such basics as grain. It is known that a population will react massively when the immediate means of survival, whether food or housing, are gone after. The speculators had to attempt to orchestrate the pre-selected popular images of rage. Should a head of state be held responsible for recognizing a level of evil that would go beyond leeching and actually physically destroy the nation? Mozart and da Ponte were insistent upon this matter.

Da Ponte vs. "Don Casanova"

Da Ponte at Columbia College (now Columbia University) in New York City. |

In 1786, Casanova proceeded to send his own exposé of Cagliostro, "Le Soliloque d'un penseur", to Joseph II - a report calculated to be too little and too late, designed only to insinuate himself closer to the Emperor. Joseph was supposed to direct the anger he had over the targeting of his sister, from the wiles of Cagliostro to the wiles of Casanova. Over the previous year, one of Casanova's conquests, young Kasper, had left her sessions with Casanova and had been making private visits to the Emperor. Now, while it would much too tedious to catch up on the two decades of Casanova's activities46 since we left him fathering his own grandchild, some background is pertinent.

First, the Mozarts themselves had a notable experience with Casanova's operations, when Wolfgang was only eight. In 1763, the Venetian ambassador to London, Querini, met with Casanova and directed him toward London, in part to set up a lottery for George III. Upon arrival - now, try to follow - he called upon one Therese Imer, the daughter of Joseph Imer, the former lover of Casanova's mother. (Casanova's sense of equity, being a chevalier, included leaving Therese with a child, Sophie.) Therese was now Mme. Cornelys, who ran a high-class bordello for royalty, at London's Carlisle House - 'high class' because she added occasional balls and concerts. It was at one such ball (January 24, 1764) that Emmanuel Morosini, of the Venetian embassy, introduced Casanova around - and he got to meet the infamous Sir John August Hervey, the British Commander in Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet.47 And what of Wolfgang? Baron von Grimm, the factotum for the duc d'Orleans, directed Leopold Mozart to take his two children to Mme. Cornelys to perform! Grimm advice, indeed! He then had his colleague, the Duke of York, a regular patron of the establishment, press Cornelys on the importance of using the Mozarts to put on a front. The only happy news is that Casanova himself had left Cornelys and England, short of money and with a social disease, about six weeks before the Mozarts arrived. They only had to deal with his mistress.

Casanova's Venetian Sponsors

Casanova's long-term financial supporters, from as early as 1746, were three occultist Venetian nobles, who cohabited in one Venetian palace: Senator Matteo Bragadin, a former Inquisitor, Marco Barbaro and Marco Dandolo, a member of the Great Council. Only Dandalo was still alive, when, in 1774, he arranged with Senator Pietro Zaguri and procurator Lorenzo Morosini, for Casanova to have dinner with the three current Inquisitors, Francesco Grimani, Francesco Sagredo and Paolo Bembo. They laughed over Casanova's supposed escape from the Leads prison two decades earlier, and cleared him for future official projects. This means that, unlike the previous two decades, now there were some official records. (Curiously, his memoirs are discontinued at just this point.) Casanova was employed as an official Venetian spy during the period of the American Revolution - or, as he put it, an "occasional Confidant" of the Inquisitors. The occasional Confidant was paid fifteen ducats a month. In 1776, two known reports indicate that his assignment was Joseph II. One is regarding whether Joseph is serious about invading Dalmatia; another, whether he will collaborate with the French in making Fiune (= Rieka), on the Adriatic coast of Italy, a port for France's use. After Yorktown, his salary ends and he has to work again 'off the reservation'.

Before taking up his post in Vienna in 1784, Casanova visited Paris. From there he wrote to the Abbe Eusebio Della Lena, of his exasperation with Benjamin Franklin. The Abbe, along with Ambassador Foscarini, would be Casanova's controllers in Vienna, so he was interested in impressing them. Casanova claims that he overheard Condorcet (11/23/1783) at the French Academy of Science, asking Franklin about the possibilities of steering the new Montgolfier balloon, and hearing him respond: "This thing is still in its infancy, therefore we must wait." This already sounds like a variation upon Franklin's well-reported comment (e.g., the September, 1783 "Mercure de France"): "Gentleman, it is a child that has just been born; perhaps it will turn out an idiot or a man of great talent. Let us wait until its education is complete before judging it." However, Casanova's sin is not mere thievery for his 'intelligence' reports. He goes on to write the Abbe: "I was surprised. It is unthinkable that the great doctor ignored that it was impossible to give to the machine a direction other than that depending directly on the wind that was blowing." Casanova certainly wanted to impress his overseer that he, also, was profoundly against the highly-charged and optimistic idea with which Franklin had just electrified Paris in 1783 - that new scientific inventions and ideas were as natural as babies, and that they must be nurtured and developed for the long term - certainly not a 'free trade' notion. Franklin's confident optimism also resonated with the political possibilities of the new American republic. Though Casanova actually exposed both his ignorance of science and his blind faith in invisible powers, be that the invisible wind or an invisible hand, it did not disrupt his new posting at the Venetian embassy in Vienna.

Casanova Does Vienna

In February, 1784, he moves to Vienna and officially enters the service of Sebastiano Foscarini, the Venetian ambassador to Vienna. Immediately, he is off on a mission, running after Joseph II with a couple of his women.48 Da Ponte reported on another incident where Casanova is aiming at the Emperor. While da Ponte was talking with Joseph about an opera (which, given the timing, might have been "Figaro"), Casanova burst in, trying to turn Joseph's interest to a 'Chinese fiesta' for Vienna. Joseph thought Casanova strange and promptly turned down the offer. When Casanova was dismissed, and they resumed their discussion on the opera, da Ponte reported that the bewildered Joseph chortled three times, "Giacomo Casanova!" Following the death of Foscarini (4/23/1785) from gout, Casanova arranges sponsorship by Count Joseph Karl von Waldstein,49 whom he had met the year before at one of Foscarini's dinners. They share a fascination for the Kabbala. He becomes Waldstein's librarian at Dux, about fifty miles from Prague, the position he holds until his own death fourteen years later.

Da Ponte would have heard of the notorious Casanova before their introductions in 1776, in Venice, at the home of the patrician Senator, Bernardo Memmo. At that time, da Ponte had been employed by one of Casanova's supporters, Senator Zaguri.50 When Casanova arrived in Vienna, da Ponte was more than a little interested in tracking his affairs. In one story from his Memoirs, he relates that, when the two of them were strolling along the Graben, Casanova recognized a former underling, Giovachino Costa, who, two decades ago, had scampered off with monies that Casanova had scammed from a wealthy and crazy Marquise, d'Urfe.51 Da Ponte witnessed how enraged Casanova became, but also how quickly he became sophisticated and urbane when Costa reminded him that it was he who taught him how to be a crook! Da Ponte's perceptive eye made note of such behavior for his characterizations of Giovanni and his underling, Leporello.

Kasper, the Friendly Whore

On April 12, 1786, shortly before the premiere of "Figaro", "Caton M", another of Casanova's conquests to whom he had promised marriage, writes from Vienna to Casanova at Dux, complaining that da Ponte is on to them. First, she brags to Casanova of her new lovers, "Count de K. and Count de M." She continues: ".[B]ut at the house of the latter, there was always an officer who pleased me more than both the two others. I do not seek to justify my past conduct; on the contrary, I know well that I have acted badly." After waving her three lovers in front of Casanova, she complains of da Ponte's visit and of his denunciation. Then, a following letter (July 16) refers to Kasper's regular visits to the Emperor: "I have spoken with the Abbe da Ponte. He invited me to come to his house because, he said, he had something to tell me for you. I went there, but was received so coldly that I am resolved not to go there again. Also, Mlle. Nanette affected an air of reserve and took it on herself to read me lessons on what she was pleased to call my libertinism... I beg that you will write nothing more about me to these two very dangerous personages... The young, little Kasper, whom you formerly loved" needs to contact you, and she is "a girl in whom the Emperor interests himself, for it is known that, since your departure from Vienna, it is he who is teaching her French and music; and apparently he takes the trouble of instructing her himself, for she often goes to his house to thank him for his kindnesses to her, but I know not in what way she expresses herself."52

It is not likely that this Kasper had changed hands from Casanova to Joseph in 1785 without Casanova's knowledge. His Memoirs display a keen sense with regard to these matters. In this letter, Caton M., another former 'betrothed', was jealous of Kasper ("who was once the favorite of my lover") and was trying to extort a long letter from Casanova in return for information from Kasper. If Casanova really was solely dependent for information about Kasper via Caton M., then this letter would suggest that his communications system about Kasper's dealings with the Emperor was disrupted from the bumps and bruises of jealousy. Casanova undoubtedly had other sources, though it is only here do we find a surviving, explicit reference to Kasper.

It should be noted that Joseph II had been a bachelor for twenty years. He had lost his young bride, Isabella53, the grand-daughter of Louis XV, to smallpox when he was only twenty-two, and their only child four years later. Though he was reluctant to remarry, for political reasons he agreed to marry Maria Josepha of Bavaria - but when she died of smallpox two years later, he refused to consider marriage again.54 This part of his personal life was, if not an open sore, at least tender - and certainly known to intelligence agencies.

Sometime in September, 1787, weeks before the scheduled performance of "Don Giovanni", Joseph II makes a trip to Dux to see Casanova!55 One must assume that, by his original approval of the "Don Giovanni" opera, at least part of him sincerely wished to explode the Venetian operations that poison Vienna. However, he must also have concerns as to what Casanova is going to do when the opera hits the stage. Beyond this, it cannot be discounted that he has concerns as to how the Kasper matter will play out. Clearly, the opera is going to destabilize a couple of levels of behind-the-scenes operations. It is not clear whether Joseph was only reading the riot act to Casanova or also attempting to manage him. Regardless, the Emperor did not need to travel from Vienna to fifty miles farther than Prague in order to examine a large library presided over by a curious librarian.

Mozart: Abandon Ship?

By no later than the summer of 1786, da Ponte and Mozart know that they have done their best for the Emperor with "Figaro", that something is amiss, and that the Venetian agent Casanova is playing games with the Emperor. It is not obvious that one can use the stage to tackle this sort of situation. At first, Mozart is convinced that the battle is lost, and that it is time to leave Vienna. No later than November, he has arranged for a long visit, or possibly a permanent move, to London. Performing in England, as Haydn would prove a few years later, could be very remunerative - and, it is not as if England was missing a republican movement that Mozart could aid and abet. In mid-November, Leopold reports to his daughter that Mozart wants him to take care of his children, which may end up being for a long time. Making arrangements for Mozart are his English friends: Michael Kelly, the Don Basilio in 'Figaro'; Ann Storace, his 'Susanna'; her husband, composer Stephen Storace; and Mozart's student, Thomas Attwood - whose sponsor was the Prince of Wales.

Mozart's plan to depart catches peoples' attention. On January 12, 1787, Leopold writes again: "I am still receiving from Vienna, Prague, and Munich reports which confirm the rumor that your brother is going to England." And still, during his first week in Prague, Mozart writes (1/15/1787) to his good friend, Gottfried von Jacquin, in Vienna: ".[A]fter my return [to Vienna in February] I will enjoy only for a short while the pleasure of your valued society and will then have to forgo this happiness for such a long time, perhaps forever.". However, within weeks his plans have changed.

"Mass Strike" in Prague

First, "Figaro" had taken Prague by storm in the Fall of 1786, and "a society of distinguished connoisseurs and enthusiasts" headed by Count Thun extended a warm invitation to Mozart. Prague had not forgotten the musical and political intervention of Mozart's "Abduction" when it had been performed there in 1782. The arrests and nastiness of Vienna had not soured or distorted Prague's appreciation. Now, Pasquale Bondini's theater company had relit that fire. Mozart quickly agreed to go, and in early January, 1787, left for Prague. There he found, as he reported to Jacquin, "they talk about nothing but 'Figaro'. Nothing is played, sung or whistled but 'Figaro'. No opera is drawing like 'Figaro'. Nothing, nothing but 'Figaro'." A young musician, Niemetschek, reported: "Figaro's tunes echo through the streets and the parks; even the harpist on the alehouse bench had to play 'Non piu andrai' if he wanted to attract any attention at all."56

While the whole Austro-Hungarian Empire was starved for progressive economic and political development, Prague, an intellectual and cultural center for centuries, was chafing at the bit for real reform. They had been subjected since the beginning of the (1618-1648) Thirty Years War, and they took Joseph's reforms as a serious matter. Their response to "Figaro" was electric. Da Ponte wrote of the reception: "The numbers which are least admired in other countries are by this people considered divine; and. the great beauties of the music. were perfectly understood by the Bohemians at the first hearing."57 Mozart was in the midst of a cultural mass strike. On January 19th, Mozart led his "Prague" Symphony at the National Theater and then played three extended improvisations, the last one on "Non piu andrai". And Niemetschek: "We did not, in fact, know what to admire most, whether the extraordinary compositions or his extraordinary playing; together they made such an impression on us that we felt we had been bewitched. When Mozart had finished the concert he continued improvising alone on the piano for half an hour. He counted this day as one of the happiest of his life."58

To the Mountaintop

Eleven days later, his closest friend unexpectedly died. Count August von Hatzfeld was Mozart's age. A year earlier, in February, 1786, he had come to Vienna to study Mozart's musical breakthroughs - in particular, his six "Haydn" String Quartets - and thereby became very close to Mozart. Beethoven's teacher, Neefe, wrote that Hatzfeld, a violinist, "became acquainted with Mozart. He . played his famous 'quadros' [the 'Haydn' quartets] under the author's guidance, and became so intimate with their composer's spirit that the latter became almost disinclined to hear his masterpiece from anyone else. Some two months before his death, I heard him deliver them with an accuracy and fervor which excited the admiration of every connoisseur and enchanted the hearts of all."59 Hatzfeld, who, along with Mozart and Neefe, made it onto Count Pergen's secret police list as 'Illuminists', had made arrangements to move to Vienna. He died January 30, 1787, at age thirty-one, reportedly of pulmonary infection.

In February, 1787, Mozart's reflections upon mortality and his own mission in life coalesced. Certainly Prague afforded him a new flank for breaking open Vienna and the Austro-Hungarian Empire; but he, and da Ponte, were contemplating open confrontation with some of the deepest and darkest aspects of Venetian methods of psychological manipulation. Over five years of reflection upon Mendelssohn's Phaedon60, his treatment of Socrates' historic mission and his last day on earth, came into focus. Mozart recorded his thoughts to his father, but unfortunately in a letter that was mislaid. Reference to the missing February letter is made in his April 14, 1787 letter61 - in what would be his last letter to his father:

"But now I hear that you are really ill. [If so, you must not hide it from me.] I have now made a habit of being prepared in all affairs of life for the worst. As death, when we come to consider it closely, is the true goal of our existence, I have formed during the last few years such close relations with this best and truest friend of mankind, that his image is not only no longer terrifying to me, but is indeed very soothing and consoling! And I thank my God for graciously granting me the opportunity (you know what I mean) of learning that death is the key which unlocks the door to our true happiness. I never lie down at night without reflecting that - young as I am - I may not live to see another day. Yet no one of all my acquaintances could say that in company I am morose or disgruntled. For this blessing I daily thank my Creator and wish with all my heart that each one of my fellow-creatures could enjoy it. In the letter which Madame Storace took away with her62, I expressed my views to you on this point, in connection with the sad death of my dearest and most beloved friend, the Count von Hatzfeld. He was just thirty-one, my own age. I do not feel sorry for him, but I pity most sincerely both myself and all who knew him as well as I did."