“Poet of Freedom” |

|

A Schiller Birthday Celebration! |

|

‘You can never think greatly enough about it;

‘How you carry it in your bosom, you imprint upon your deeds.’

| Helga Zepp LaRouche, founder of the international Schiller Institute, prepared the following dialogue for presentation at events to be held throughout the world to celebrate Friedrich Schiller’s birthday on November 10. In particular, the dialgoue poses the challenge to the LaRouche Youth:Movement, to take to heart the beautiful ideas bequeathed to us by this shining star of German culture and history. |

First Speaker: Good evening!

You all treasure our great “Poet of Freedom,” Friedrich Schiller, whose 244th birthday we celebrate this evening. And therefore it will be easy for you to observe the present time with his eyes, and consider from his point of view what Classical art can perhaps effect today.

Therefore, we will proceed in a manner directly opposite to that of the representatives of the avant-garde theater: We do not want to “modernize” the ideas of Schiller with the banal traits of the present time, but rather, we want to ask ourselves, how we actually stand today when measured against Schiller’s standards.

EIRNS/Chris Lewis EIRNS/Chris LewisHelga Zepp-LaRouche (left) joins members of the LaRouche Youth Movement in a Schiller birthday celebration in Mainz, Germany, November 2003. |

If we remember how Schiller described the moral conditions of his time in “On Grace and Dignity”—what would he say today? The majority of our civilization seems to be even more brutalized than in Schiller’s time. Most of humanity suffers unbearable privation, while another part is enslaved to a senseless desire for consumption. A spiral of violence terrorizes mankind in ever more regions of the world, but oddly enough, we find this violence in films, on television, and the internet to be “entertaining”—otherwise the “Terminator” could not have become the Governor of California. An apparently boundless increase in pleasure-seeking by part of the society, has led to the fact that the ability to distinguish between right and wrong has been widely lost: One should only not let oneself get caught, is instead the precept.

A large part of humanity lacks the minimum prerequisites for a life worthy of man, while those who are not affected manifest an astoundingly brutal indifference to this deplorable state of affairs. Universal history is full of examples that show that civilizations which exhibit a comparable paradigm, are lawfully destroyed.

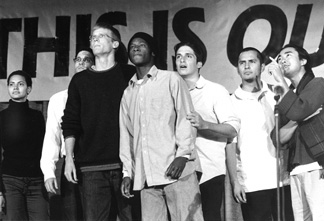

EIRNS/Stuart Lewis EIRNS/Stuart LewisLYM members perform at ICLC/Schiller Institute conference, Reston, Virginia, February 2003. |

Schiller was absolutely conscious of the fact that European history is characterized by two completely opposed traditions: One proceeds from the fact that man is only a being of sensuous experience. Plato describes this case in his famous “Cave” metaphor, where man sits in a barely lit cave, and does not regard the actual occurences taking place outside his visual sphere, but rather their shadows, as reality. Such a man, imprisoned in the world of sensuous experience and desire, is robbed of his actual humanity, and Schiller has made every effort in all of his work, in all of its aspects, to lift his reader and audience out of this miserable condition.

And thus our poet acted very polemically, for he wanted to hold up a mirror to his contemporaries imprisoned in this condition, because self-knowledge is the first step to overcoming such a problem. But, perhaps, he wrote not only for his own contemporaries; perhaps he had a presentiment of the public in the football stadium or at the rock concert and rave-parties?

EIRNS/Stuart Lewis EIRNS/Stuart LewisLYM members present the Rütli Oath scene from Schiller’s “William Tell,” February 2003. |

Speaker A: It seems that he writes thus in “On Grace and Dignity”:

If, on the other hand, the person, subjugated by needs, allows natural instinct unfettered rule over himself, then, along with his inner autonomy, every trace of freedom in his form vanishes as well. Only bestiality speaks forth from the rolling, glassy eye, the lusting, open mouth, the strangled, trembling voice, the quickly gasping breath, the trembling limbs, from the entire flaccid form. All resistance of moral power has given way, and nature in him is set in total freedom.But, just this total cessation of self-activity, which usually ensues in the moment of sensuous longing, and even more in the enjoyment of it, also sets raw matter, previously constrained by the balance of active and passive forces, momentarily free. The dead forces of nature begin to take the upper hand over the living ones of organization; form begins to be repressed by mass, humanity by common nature.

The soul-beaming eye becomes lustreless, or stares glassily and vacant out of its socket; the fine, rosy color of the cheeks thickens into a coarse and uniform bleachy flush; the mouth becomes a mere hole, since its form is no longer the effect of active, but of waning forces; the voice and sighing breath, nothing but noises, by means of which the heavy chest seeks relief, and betrays now merely a mechanical need, but no soul.

* Excerpts from the works of Schiller are taken from the four-volume Friedrich Schiller, Poet of Freedom, ed. by William F. Wertz, Jr. (Washington, D.C.: Schiller Institute). In a word: with the freedom which sensuousness usurps unto itself, beauty is inconceivable. ... A person in this condition outrages not merely moral sensibility, which unyieldingly demands the expression of humanity; the aesthetical sensibility, too, which satisfies itself not with mere matter, rather seeks free pleasure in the form, will turn away in disgust from such a sight, in which only lusts can find their account. (Friedrich Schiller, Poet of Freedom, Vol. II, pp. 362-363*)

Youth:: But wait a minute, I think it is totally uncool, if you use people who go to rock and rave parties as an example for being imprisoned in sensuous desires. I admit that it is not especially original, when millions of young people all practice basically the same songs, to get themsleves ready for “American Idol.”

But it becomes painful, when my mother always wants to go to the disco with my sister. And when my old man with his bald head and pony tail follows his Abba nostalgia. That fits Schiller’s earlier description.

And overall, I do not find it exactly super, the kind of world the Baby Boomers gave to the present Youth:generation. Somehow, everyone thinks only about his own advantage, they have all filled their pockets—so now, when we young people want to know what the future is going to look like for us, we only hear: Save, Save, Save. Somehow that is completely stupid.

Speaker A:

In his deeds man paints himself, and what form it is, which is reflected in the drama of the present time! Here, return to a savage state; there, a state of enervation: The two greatest extremes of human degeneration, and both united in one space of time.In the lower and more numerous classes, brutal lawless instincts present themselves to us, which unleash themselves after the dissolved bond of the civil order, and hasten with unruly fury to their animal satisfaction. (“On the Aesthetical Education of Man,” Vol. I, p. 230)

On the other side, the civilized classes give us the still adverse sight of slackness and of a depravity of character, which revolts so much the more, because culture itself is its source. I no longer remember, which ancient or modern philosopher made the observation, that the more noble would be in its destruction the more horrible, but one will find it true as well in the moral. From the son of nature emerges, when he indulges in excess, a raving madman; from the pupil of art, a worthless villain. The enlightenment of the understanding, on which the refined classes not entirely with injustice pride themselves, shows in the whole so little an ennobling influence on the inner convictions, that it rather strengthens the corruption through maxims. (Vol. I, p. 231)

First Speaker: It is noteworthy that the people who have up to now profited from the ruling system, and have thought that everyone can become a millionaire by speculating on the stockmarket, seem to notice nothing about the general indolence and depravity of the character of society. Now suddenly, when it becomes obvious that not only are the bubbles in the financial markets bursting, but rather, that the real economy is in a free fall, and all coffers are empty, the satisfied complacency receives a deep rupture. The change in the values of a society in which people were proud to produce the best products in the world, back to to an amusement and consumer society, took place over 30 years in many small steps. The result is a spiritual retrogression of the whole population, as one can see in the entertainment industry, but also in academic life.

EIRNS EIRNSScene from “William Tell,” LYM cadre school, Seattle, November 2003 |

Speaker B: Schiller already spoke about this in his 1789 inaugural address at the University at Jena:

The course of studies which the scholar who feeds on bread alone sets himself, is very different from that of the philosophical mind. The former, who for all his diligence, is interested merely in fulfilling the conditions under which he can perform a vocation and enjoy its advantages, who activates the powers of his mind only thereby to improve his material conditions and to satisfy a narrow-minded thirst for fame, such a person has no concern upon entering his academic career, more important than distinguishing most carefully those sciences which he calls ‘studies for bread,’ from all the rest, which delight the mind for their own sake. Such a scholar believes, that all the time he devoted to these latter, he would have to divert from his future vocation, and this thievery he could never forgive himself. (“What Is, and To What End, Do We Study Universal History?,” Vol. II, pp. 254-55)First Speaker: The problem lies simply in the fact that in the world of sensuous experience, no solutions are possible on a higher level, because one can not at all think beyond the apparently self-evident Here and Now. The bread-fed academic is relatively harmless, but when things are treated in this way in grand politics, it leads to a catastrophe. This is the case in all of Schiller’s dramas: If the leading person, the hero, the heroine, can elevate himself above the level of sensuous self-interest, then the drama ends positively, as in the case of Joan of Arc or William Tell. If he can not do so, then the drama ends as tragedy.... Once he has run his course and attained the goal of his desires, he dismisses the sciences which guided him, for why should he bother with them any longer? His greatest concern now is to display these accumulated treasures of his memory, and to take care, that their value not depreciate. Every extension of his bread-science upsets him, because it portends only more work, or it makes the past useless; every important innovation frightens him, because it shatters the old school form which he so laboriously adopted, it places him in danger of losing the entire effort of his preceding life.

EIRNS

Scene from “William Tell,” LYM cadre school, Seattle, November 2003Who rants more against reformers than the gaggle of bread-fed scholars? Who more holds up the progress of useful revolutions in the kingdom of Knowledge than these very men? Every light radiated by a happy genius, in whichever science it be, makes their poverty apparent; their foils are bitterness, insidiousness, and desperation, for, in the school system they defend, they do battle at the same time for their entire existence. On that score, there is no more irreconcilable enemy, no more jealous official, no one more eager to denounce heresy than the bread-fed scholar.

The less his knowledge rewards him on its own account, the more he devours acclaim thrown at him from the outside; he has but one standard for the work of the craftsman, as well as for the work of the mind—effort. Thus, one hears no one complain more about ingratitude than the bread-fed scholar; he seeks his rewards not in the treasures of his mind—his recompense he expects from the recognition of others, from positions of honor, from personal security. If he miscarries in this, who is more unhappy than the bread-fed scholar? He has lived, worried, and worked in vain; he has sought in vain for truth, if for him this truth not transfer itself into gold. published praise, and princely favor.

Pitiful man, who, with the noblest of all tools, with science and art, desires and obtains nothing higher than the day-laborer with the worst of tools, who, in the kingdom of complete freedom, drags an enslaved soul around with him! (Vol. II, p. 256)

Carol Rosegg Carol RoseggThe Marquis of Posa and King Philip II, in “Don Carlos.” Shakespeare Theatre, 2001 |

For example, in Mary Stuart, the play comes to the famous exchange between the two Queens, which demonstrates how chances are squandered, if each person only allows his emotions to run freely. The English Queen, Elizabeth, the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, fears a deadly rival in the Catholic Mary. Mary, Queen of Scotland, has been raised in France, and has certain claims on the English throne. When Mary flees to England in the face of a revolt of her own lords and seeks help from Elizabeth, the latter illegally imprisons her, and executes her in 1587:

(MARYpulls herself together and wants to move toward elizabeth, but at half way stands still shuddering, her demeanor expresses the most intense struggle: ) Elizabeth: How, my Lords?

Who was it then, who did announce to me

One bowed down low? I find a prideful one,

In no way by misfortune humbled.

Mary: : Be’t!

I will submit myself as well to this.

Fare well, unconscious pride o’th’ noble soul!

I will forget, who ’tis I am, and what

I suffer, I will cast myself ’fore her,

Who thrust me into this humiliation.

(She turns towards the queen: )

The Heavens have decided for you, Sister!

Your happy head is crowned by victory,

The Godhead I adore, which raised you up!

(She falls down before her)

Yet be you also nobleminded, Sister!

Let me not lie disgracefully, your hand

Stretch out, extend to me the royal rights,

To elevate me from this deep decline.

Elizabeth (stepping back):

You’re in the place which suits you, Lady Mary!

And thankfully I praise my God’s good grace,

Who hath not wished, that at your feet I should

So lie, as you are lying now at mine.

Mary: (with mounting emotion):

Think of the change of all things human!

Gods live, who vengeance take on arrogance!

Revere them, fear them, these most dreadful ones,

Who hurled me down before your very feet—

For the sake of these strange witnesses, don’t honor

Yourself in me, profane not, sully not

The blood o’th’ Tudor, which within my veins

Flows as it doth in yours—O God in heaven!

Stand not there, rough and unavailing, like

Some rocky cliff, which one who hath been stranded

With great exertion vainly strives to seize.

My all, my life, my destiny depends

Upon the power of my words, my tears,

Release my heart, so that I may move yours!

If you regard me with this icy look,

My shudd’ring heart locks itself up, the stream

Of tears runs dry, and freezing horror fetters

The words of supplication in my bosom.

Elizabeth: (cold and stern):

What do you have to say to me, Lady Stuart?

You’ve wished to speak with me. I shall forget

The Queen, who hath been grievously abused,

To do the pious duty of the sister,

And grant I you the solace of my sight.

The drive of magnanimity I follow,

Expose myself to rightful blame, that I’ve

So far descended—for you know,

That you have wanted to effect my murder.

Mary: : By what means shall I make a start, how shall

I prudently arrange the words, so that

They grip your heart, but not give you offense!

O God, give power to my speech, and take

From it each thorn, which could do harm! Yet I

Cannot speak for myself, without severely

Indicting you, and I will not do that.

—The way you’ve acted towards me is not right,

Because I am a Queen like you, and you

Have kept me locked up as a prisoner,

I came to you as a supplicant, and you,

The holy law of hospitality,

The people’s holy right in me deriding,

Confined me inside dungeon walls, my friends,

My servants then are cruelly torn from me,

I am abandoned to unworthy want,

I’m placed before an ignominious court—

Nought more thereof! May an oblivion

Eterne bedeck, what cruelties I bore.

—See! Everything I would ascribe to fate,

You are not guilty, also I’m not guilty,

An evil spirit rose from the abyss,

To set on fire the hatred in our hearts,

By which our tender Youth:was torn in two.

It grew with us, and evil-minded men

Did fan the grievous flames with their own breath.

Insane fanatics amply did equip

With sword and dagger the uncalled for hand—

That is the curséd destiny of kings,

That they, divided, rend the world in hate,

And let the furies of all discord loose.

—Now ’twixt us there’s a foreign tongue no more,

(approaches her confidingly and with a flattering tone)

We stand now face to face with one another.

Now, Sister, speak! Point out to me my guilt,

I wish to give you total satisfaction.

Ah, that you then had granted me a hearing,

When I so urgently besought your eye!

It never would have come so far, nor would

Have happened now in this unhappy place

This miserable, unhappy rendezvous.

Elizabeth:: My lucky star protected me, so that

I did not lay the adder to my breast.

—Not destiny, but your own blackened heart

Indict, the wild ambition of your house.

Between us nothing hostile had occurred,

When your proud uncle, the imperious priest,

Who after every crown his daring hand

Extends, threw down the gauntlet unto me,

Deluded you, to take my coat of arms,

To claim my royal title as your own,

To enter into mortal combat with me—

Whom did he not call up to fight against me?

The priest’s tongue-lashing and the people’s sword,

The frightful arms of pious lunacy,

Here even, in my kingdom’s peaceful seat,

He fanned the flames against me of revolt—

Yet God is with me, and the prideful priest

Did not retain the field—My head it was

The stroke had threatened, and its yours which falls!

Mary: : I stand i’th’ hand of God. You won’t exempt

Yourself so bloodily from pow’r that’s yours—

Elizabeth:: Who then shall hinder me? Your uncle gave

The standard for all kings throughout the world,

How one concludes a peace with enemies,

My school be that of Saint Bartholomew!

To me what’s blood relation, nation’s law?

The church can break the bands of every duty,

It hallows breach of truth and regicide,

I practice only that which your priests teach.

Say then! What pledge is granted me for you,

If I magnanimously release your bonds?

And with what lock can I secure your faith,

Which by Saint Peter’s key cannot be opened?

My only surety is force alone,

There’s no alliance with the brood of snakes.

Mary: : O that is your unhappy dark suspicion!

You’ve constantly regarded me as but

An enemy and foreigner. Had you

Declared me as your heiress, as to me

Is due, so had then gratitude and love

In me obtained for you a loyal friend

And relative.

Elizabeth:: Abroad, my Lady Stuart,

Your friendship is, your house the papacy,

Your brother is the monk—yourself, declare

To be the heiress! The perfidious snare!

That yet within my life you would seduce

My people, a duplicitous Armida

Entangle cunningly the noble Youth:Throughout my realm within your wanton nets—

That all would then devote themselves to th’ new

Arising sun, and I—

Mary: : Would rule in peace!

I give up any claim upon this realm.

Alas, my spirit’s pinions have been lamed,

Greatness no longer tempts me—You’ve attained

It, I am only Mary’s shadow now.

In lengthy prison shame my noble valor

Hath broken down—You’ve done the uttermost

To me, you have destroyed me in my bloom!

—Now bring it to an end, my sister. Speak

The word, for whose sake you have now come here,

For ne’er will I believe, that you have come,

In order cruelly to deride your victim.

Pronounce this word. Say to me: “Mary, you

Are free! You have already felt my power,

My generosity now learn to honor.”

Say it, and I will then receive my life,

My freedom as a present from your hand.

—One word makes everything undone. I wait

For it. O let me not too long await it!

Woe’s you, if with this word you do not end!

For if not bringing blessings, gloriously,

Like to a Godhead you now leave me—Sister!

Not for this whole abundant island, not

For all the countries, which the sea embraces,

Would I ’fore you thus stand, as you ’fore me!

Elizabeth:: Do you at last admit you are defeated?

Are your intrigues now done? No more assassins

Are on the way? Will no adventurer

For you again his doleful knighthood venture?

—Yes, it is finished, Lady Mary. You’ll seduce

None more ’gainst me. The world hath other cares.

No one is covetous of being your—

Fourth husband, for your suitor you destroy,

Just like your husbands!.

Mary: (starting): Sister! Sister!

O God! God! give me self-control!

Elizabeth: (regards her at length with a look of proud disdain):

Those then, Lord Leicester, are the winsome charms,

Which no man views unpunished, next to which

No other woman may dare place herself!

Forsooth! This fame was cheaply to be gained,

To be the universal beauty costs

Nothing but to be commonplace for all!

Mary: : That is too much!

Elizabeth: (laughing derisively):

Now you are showing your

True face, ’til now ’twas but the mask.

Mary: (fuming with rage, yet with a noble dignity):

My failures have been human and from Youth:,

I was seduced by pow’r, I have it not

Concealed and kept in secret, false appearance

I have despised, with royal candidness.

The worst of me the world knows well and I

Can say, that I am better than my fame.

Woe’s you, when from your deeds it one day draws

The cloak of honor, with which you with glister

Conceal the savage fire of furtive lusts.

Not worthiness did you inherit from

Your mother, one knows, for which virtue’s sake

Anne Boleyn was compelled to mount the scaffold. ...

... I have

Endured what human nature can endure.

Fare well, lamb-hearted equanimity. ...

The throne of England by a bastard is

Profaned, the noble-hearted British people

Have been defrauded by a cunning juggler.

—If right did rule, then in the dust you now

Would lie before me, for I am your king.

(Elizabeth

exits quickly, the lords follow her in highest dismay: ) (Mary Stuart, Vol. IV, pp. 152-158)

Young Girl: My goodness, that’s quite a fight!

Carol Rosegg Carol RoseggDon Carlos and Elizabeth, now Queen, in “Don Carlos,” Shakespeare Theatre, 2001 |

First Speaker: Yes, if the piece were to end there, then it would almost be modern. But with Schiller, Mary now undergoes a development, she achieves a sublime state of mind, and even though Elizabeth has her killed, Mary is internally free.

But Schiller also has examples in his dramas, of how his heroes can struggle to rise from the level of sensuous entanglement to the level of reason. In Don Carlos, for example, Elizabeth succeeds in pulling Carlos out of his “Schwaermerei” and in making him conscious of his historical responsibility.

Speaker A: Don Carlos, the heir to the Spanish throne, was engaged to Elizabeth of Valois, before his father, Philip II, married her—making her Queen of Spain, and Carlos’s step-mother. Carlos has not reconciled himself with this, and nurtures the love of his previous financee, which in the Spain of the Inquisition is naturally hopeless.

Carlos: (thrown down before the QUEEN: ):

So is it finally here, the precious moment,

And Carl may dare to touch this cherished hand!—

Queen:: What kind of step—and what a culpable,

Adventuresome surprise! Stand up! We are

Discovered now. My retinue’s nearby.

Carlos:: I’ll not stand up—here will I ever kneel.

Upon this spot I’ll lie enchantedly.

I shall take root in this position—

Queen:: Madman!

Unto what boldness doth my favor lead you?

How? Do you know, that ’tis the Queen, that ’tis

The mother, to whom this audacious speech

Is now directed? Do you know, that I—

That I myself of this surprise invasion

Unto the King—

Carlos:: And that I then must die!

They’d drag me straight from here onto the scaffold!

One moment, to have lived in paradise,

Will not be bought too dearly with my death.

Queen:: And what then of your Queen?

Carlos: (stands up): God, God! I’ll go—

I shall indeed foresake you.—Must I not,

When you demand it thusly? Mother! Mother!

How frightfully you play with me! One sign,

One half a glance, one sound from out your mouth

Enjoins me, both to be and pass away.

What do you want, that yet should come to pass?

What can there be beneath this sun, that I

Will not make haste to sacrifice, if you

So wish it?

Queen:: Fly from me.

Carlos:: O God!

Queen:: This one

Thing only, Carl, wherefore I conjure you

With teardrops—Fly from me!—before my ladies—

Before my jailers find you here with me

Together, and then bring the major news

Before your father’s ears—

Carlos:: I shall await

My destiny—and be it life or death.

What? Have I concentrated all my hopes

Upon this single moment, which doth grant

You to me without witnesses at last,

That bogus terrors duped me at the goal?

No, Queen! The world can move a hundred times,

A thousand times upon its poles before

This favor of coincidence repeats.

Queen:: And that it should not in eternity.

Unhappy man! What do you want from me?

Carlos:: O queen, that I have struggled, struggled, as

No mortal ever struggled to this day,

Let God then be my witness—Queen, in vain!

Behind me is my valor. I succumb.

Queen:: No more of this—for my repose’s sake—

Carlos:: You once were mine—in view of all the world

Awarded to me by two mighty thrones,

Conferred on me by heaven and by nature,

And Philip, Philip’s stolen you from me—

Queen:: He is your father.

Carlos:: And your husband.

Queen:: Who

Bequeaths to you the world’s most mighty realm.

Carlos:: And you as mother—

Queen:: Mighty God! You rave—

Carlos:: And knows he too how rich he is? Hath he

A feeling heart, to treasure that of yours?

I’ll not lament it, no, I shall forget,

How happy past all utterance were I

Become to have your hand—if he but is.

But he is not.—That, that is hellish torment!

That he is not and never shall become.

Thou tookst my heaven from me, only to

Annihilate it there in Philip’s arms.

Queen:: Abominable thought!

Carlos:: O yes, I know,

Who was the author of this marriage—and

I know, how Philip loves and how he woo’d.

Who are you then within this realm? Let’s hear,

By chance, the Regent? Nevermore! Where you’re

The Regent, how then could these Albas slaughter?

And how could Flanders bleed for its belief?

Or are you Philip’s wife? Impossible!

This I cannot believe. A wife possesses

The husband’s heart—to whom doth his belong?

And doth he not, for every tenderness,

That might escape from him in feverish ardor,

Apologize unto his scepter and

To his grey hairs?

Queen:: Who told you, that my lot

Be worthy of lament at Philip’s side?

Carlos:: My heart, that strongly feels, how enviable

At my side ’twere.

Queen:: Conceited man! If my

Own heart now said the opposite to me?

If Philip’s deferential tenderness,

Should move me far more intimately than

His haughty son’s audacious eloquence?

If an old man’s considerate regard—

Carlos:: Then that is different—then—yet, then—your pardon.

I did not know it, that you love the King.

Queen:: My wish and pleasure is to honor him.

Carlos:: Then you have never loved?

Queen:: Peculiar question!

Carlos:: Then you have never loved?

Queen:: —I love no more.

Carlos:: Because your heart, because your vow forbids it?

Queen:: Depart from me now, Prince, and do not come

For such a conversation e’er again.

Carlos:: Because your vow, because your heart forbids it?

Queen:: Because my duty—Hapless one, whereto

The sad dissection of the destiny

That you and I must both obey?

Carlos:: We must?

We must obey?

Queen:: What? what is it you want

With this most solemn tone?

Carlos:: So much, that Carlos

Is not disposed, to must, where he hath but

To will; that Carlos is not so disposed

To stay the one most miserable i’th’ realm,

When it should cost him but the overthrow

Of laws, and nothing more, to be the one

Most blissful.

Queen:: Do I understand you now?

You yet do hope? You venture it, to hope,

Where every, everything’s already lost?

Carlos:: I give up naught for lost except the dead.

Queen:: On me, upon your mother, rest you hopes?—

(She views him long and penetratingly—then with dignity and earnestness)

Why not then? Oh! The new elected King

Can do yet more than that—can extirpate

Decrees of the departed one through fire,

Can fell his images, and what is more—

Who should prevent him?—drag the dead one’s mummy

From its repose in the Escurial

Into the light o’th’ sun, and strew about

His desecrated dust to the four winds

And last, to consummate it worthily—

Carlos:: For love of God, do not complete the thought!

Queen:: At last he can yet marry with his mother.

Carlos:: Accursed son!

(He stands a moment blank and speechless.) Yes, it is out. Now is

It out—I feel it clear and bright, that which

Should ever, ever dark remain for me.

For me you’re gone—gone—gone—forevermore!—

And now the die is cast. You’re lost to me.—

Oh, Hell doth lie within this feeling! Hell

Doth lie in yet another feeling, in

Possessing you.—Alas! I grasp it not,

And now my nerves are at the breaking point.

Queen:: Lamentable, O precious Carl! I feel—

I feel completely this, the nameless pain,

That storms now in your bosom. Infinite’s

Your torment, like your love. Yet infinite

Alike’s the glory, this to overcome.

Attain it, youthful hero. The reward

Is worthy of this strong and lofty fighter,

Is worthy of the Youth:, through whose heart rolls

The virtue of so many regal forbears.

Take courage, noble Prince.—The grandson of

The mighty Carl shall start afresh to struggle,

Where others’ children end dejectedly.

Carlos:: Too late! O God! it is too late!

Queen:: To be

A man? O Carl! How great our virtue grows,

When in its exercise our heart doth break!

‘Twas high that Prov’dence placed you—higher, Prince,

Than millions of your other brothers. She,

In partiality gave to her favorite,

What she from others too, and millions ask:

Did he deserve to count in Mother’s womb

For more already than we other mortals?

Up, vindicate the equity of Heaven!

Deserve to walk before the rest o’th’ world,

And sacrifice, what none have sacrificed!

Carlos:: That I can do as well.—to fight for you,

I have a giant’s strength, to lose you, none.

Queen:: Confess it, Carlos—‘tis but spitefulness

And bitterness and pride, that draws your wishes

So fiercely to your mother. That same love,

The heart, you offer wastefully to me,

Belongs to th’ realms, that you should rule in days

To come. You see, you squander all the goods

That in your trust your ward hath held for you.

Love is your greatest office. But ’til now

It’s stray’d unto your mother.—Bring it now,

O, bring it now to your prospective realms

And feel, instead of daggers of the conscience,

Just how voluptuous ’tis to be God.

Elisabeth was your first love. Be Spain

Your second love! How gladly, my good Carl,

Will I give way to th’ loftier Beloved!

Carlos: (throws himself, overwhelmed with feeling, at her feet):

How great you are, O Heavenly!—Yes, all

You charge me with, that shall I do!—So be’t!

(He arises.)

I stand here in th’ Almighty’s hand and swear—

And swear to you, I swear eternally—

O Heaven! No! Eternal silence only,

Yet not to e’er forget it.

Queen: How could I

Demand of Carlos, what I am myself

Unwilling to perform?

(Don Carlos, Infante of Spain, Vol. I, pp. 21-25)

EIRNS/Chris Lewis EIRNS/Chris LewisHelga Zepp-LaRouche with LYM, Schiller Birthday, Wiesbaden, Germany, November 2003. |

INTERMISSION |

Youth:: If I understand this last scene correctly, then Elizabeth and Carlos renounced their love—for the sake of the greater cause. Carlos should later become King and govern better than Philip. That’s called self-denial—but you call Schiller the “Poet of Freedom.” Where’s the freedom here?

First Speaker: Schiller is called the “Poet of Freedom” above all, because in all his works he attempted in ever new ways to make his readers and audience internally free, and because he completely rejected every form of force, whether external or internal. Thus, for example, he begins his History of the Revolt of The Netherlands from the Spanish Government:

Speaker C:

First Speaker: Schiller was himself astonishingly clear that the two traditions in European philosophy—the world of sensuous knowledge alone, on the one hand, and the real world of universal principles, on the other—were also connected to two completely different political systems. The oligarchical system, in which a small power-elite rules over a mass of men, consciously kept backward, he described incredibly insightfully in “The Legislation of Lycugus and Solon”:One of the most remarkable among the events of state, which have made the Sixteenth century the most splendid in the world, seems to me the establishment of The Netherlands’ freedom. If the glittering deeds of glory-seeking and a destructive appetite for power lay claim to our admiration, how much more so an event, where an oppressed humanity struggles for its noblest rights, where the good cause is paired with unaccustomed powers, and the resources of resolute desperation triumph over the fearsome arts of tyranny in unequal combat. Great and comforting is the reflection, that against defiant usurpations by monarchic force, in the end a remedy is still at hand, that their most calculated designs against human freedom can be spoiled, that a bold-hearted resistance can bend low even the outstretched hand of a despot, heroic perseverance can finally exhaust his terrifying resources. Never did this truth pierce me so vividly as the history of that memorable revolt, which severed the United Netherlands forever from the Spanish crown—and on that account, I regarded it as not unworthy of the effort to set before the world this beautiful memorial of common citizens’ strength, to awaken in the breast of my reader a joyful sense of his own individual self, and to give a new incontestable example, of what human beings can dare to hazard for the cause, and what they may accomplish by uniting together. (Vol. III, pp. 177-78)

EIRNS/Brendon Barnett

LYM chorus rehearsal at Los Angeles cadre school, April 2003

Speaker D:

Youth: Yes, this criterion should be applied each time to one’s own state—before one declares another country to be a rogue nation and invades it.But if one compares the aims Lycurgus set himself with the aims of mankind, then profound disapproval must take the place of the admiration, which our first fleeting glance enticed from us. Everything may be sacrificed for the best of the state, but not that, which serves the state itself only as an instrument. The state itself is neveR the purpose, it is important only as the condition under which the purpose of mankind may be fulfilled, and this purpose of mankind is none other than the development of all the powers of people, i.e., progress. If the constitution of a state hinders the progress of the mind, it is contemptible and harmful, however well thought-out it may otherwise be, and however accomplished a work of its kind.

In general, we can establish a rule for judging political institutions, that they are only good and laudable, to the extent, that they bring all forces inherent in persons to flourish, to the extent, that they promote the progress of culture, or at least not hinder it. This rule applies to religious laws as well as to political ones: both are contemptible if they constrain a power of the human mind, if they impose upon the mind any sort of stagnation. ... [S]uch a law were an assault against mankind ... . (Vol II, pp. 283-284)

Speaker D: But Schiller goes even further:

Universal human emotions were smothered in Sparta in a way yet more outrageous, and the soul of all duties, respect for the species, was irrevocably lost. A law made it a duty of the Spartans to treat their slaves inhumanly, and in these unfortunate victims of butchery, humanity was cursed and abused. The Spartan Book of Laws itself preached the dangerous principle, that people be considered as means, not as ends—the foundations of natural law and morality were thereby torn asunder, by law.

All industry was banned, all science neglected, all trade with foreign peoples forbidden, everything foreign was excluded. All channels were thereby closed, through which his nation might have obtained more enlightened ideas, for the Spartan state was intended to revolve solely around itself, in perpetual uniformity, in a sad egoism. (Vol. II, p. 285)

However, we have seen that progress of the mind should be the aim of the state.

First Speaker: Progress of the mind as an inalienable right of mankind, that was exactly the idea, which was fought for practically for the first time in the American Revolution of 1776, and was expressed in the Declaration of Independence and the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution. This was the theme in the 80’s of the Eighteenth century, with which all republican circles in Europe were concerned. Schiller himself at one point even wanted to emigrate to the U.S.A. and make a “great leap.” In Don Carlos, he transferred the fight for these ideas to the Spanish court of the Sixteenth century.

Youth: Wait a minute, are you asserting that Schiller was thinking about the political revolutions in his own time, when he wrote Don Carlos? How do you know that?

First Speaker: Among other sources, from Schiller’s “Letters on Don Carlos,” where he writes about the decade in which the American Revolution was made:

Recall, dear friend, a certain discussion, which about a favorite subject of our decade—about spreading of a purer, gentler humanity, about the highest possible freedom of the individual within the state’s highest blossom, in short, about the most perfect condition of man, as it in his nature and his powers lies given as achievable—among us became lively and enchanted our fantasy in one of the loveliest deams, in which the heart revels so pleasantly.

What is not possible to fantasy? What is not permitted to a poet? Our conversation had long been forgotten, as I in the meantime made the acquaintance of the Prince of Spain; and soon I took note of this inspirited Youth:, that he indeed might be that one, with whom we could bring our design to realization. Thought, done! Everything found I, as through a ministering spirit, thereby played into my hands; sense of freedom in struggle with despotism, the fetters of stupidity broken asunder, thousand-year-long prejudices shaken, a nation, which reclaims its human rights, republican virtues brought into practice, brighter ideas into circulation, the minds in ferment, the hearts elevated by an inspired interest—and now, to complete the happy constellation, a beautifully organized young soul at the throne, come forth under oppression and suffering in solitary unhindered bloom. Unhappy—so we decided—must the king’s son be, in whom we wanted to bring our ideal to fulfillment. (Vol. I, pp. 195-96)

Speaker E:

From the bosom of sensuality and fortune might he not have been taken; art might not yet have lain a hand on his character, the world at that time might not yet have impressed its stamp on him. But how should a regal Prince of the Sixteenth century—Philip II’s son—a pupil of monks, whose hardly awakening reason is watched by such severe and sharp-sighted guardians, acquire this liberal philosophy? Behold, this too was provided for. Destiny gave him a friend—a friend in the decisive years, where the blossoms of the spirit unfold, ideals are conceived and the moral sentiment is purified—a spiritually rich, sensitive Youth:, over whose education itself, what hinders me, to suppose this? a favorable star hath watched ... . An offspring of friendship thus is this bright human philosophy, which the Prince will bring into practice upon the throne. it clothes itself in all the charms of Youth:, in all the grace of poetry; with light and warmth it is deposited in his heart, it is the first bloom of his being, it is his first love.

Among both friends forms thus an enthusiastic design, to bring forth the happiest condition, which is achievable to human society, and of this enthusiastic design, how it namely appears in conflict with the passion, treats the present drama. The point was thus, to put forward a Prince, who should realize the highest possible ideal of civil bliss for his age. (Vol. I, pp. 196-197)

First Speaker: Yes, that was an important thought of Schiller’s, to hold, as an adult, the dreams of his Youth:in respect. However, unfortunately his hope was not fulfilled, that the American Revolution would be repeated in all of Europe, first in France and then in Germany.

When, under the leadership of Lord Shelburne, the Martinists in France inspired and used, first, the Jacobin Terror, and then, the imperial plan of Napoleon, precisely to prevent such a repetition of the American Revolution in Europe, Schiller was appalled and wrote: “the great moment has found a little people, the objective chance was given, but the subjective moral possibility was lacking.”

In the “Song of the Bell,” Schiller describes the French Revolution thus:

Speaker F:

The Master can break up the framing

With wisen’d hand, a rightful hour,

But woe, whene’er in brooks a-flaming

Doth free itself, the glowing ore!

Blind-raging with the crash of thunder,

It springs from out the bursted house,

And as from jaws of hell asunder

Doth spew its molten ruin out;

Where senseless powers are commanding,

There can no structure yet be standing,

When peoples do themselves set free,

There can no common welfare be.

Woe, when in womb of cities growing,

In hush doth pile the fiery match,

The people, chains from off it throwing,

Doth its own help so frightful snatch!

There to the Bell, its rope-cord pulling,

Rebellion, doth it howling sound

And, hallowed but for peaceful pealing,

To violence doth strike aloud.

Liberty, Equality! men hear sounding,

The tranquil burgher takes up arms,

The streets and halls are all abounding,

And roving, draw the murd’ring swarms;

Then women to hyenas growing

Do make with horror jester’s art,

Still quiv’ring, panther’s teeth employing,

They rip apart the en’my’s heart.

Naught holy is there more, and cleaving

Are bonds of pious modesty,

The good its place to bad is leaving,

And all the vices govern free.

To rouse the lion, is dang’rous error,

And ruinous is the tiger’s bite,

Yet is most terrible the terror

Of man in his deluded state.

Woe’s them, who heaven’s torch of lighting

Unto the ever-blind do lend!

it lights him not, ’tis but igniting,

And land and towns to ash doth rend.

(Vol. II, p. 51)

Young Girl: I understand that the terror destroyed the French Revolution. But how can one develop the “little generation,” the “little people,” so that they no longer respond in a “small-minded” way?

First Speaker: That was exactly the decisive question for Schiller. He was convinced that from then on, every improvement in the political domain would only be possible through the ennoblement of the individual.

Young Girl: But how is this ennoblement supposed to occur?

First Speaker: Schiller found that Classical art must play a decisive roll: the theater, for example, or the stage. The public could grapple with the great subjects of humanity in great historical dramas.

Youth: Stated simply, Schiller also left something in writing about this.

Speaker D: That is so. In his writing on “Theater Considered as a Moral Institution,” it says:

One noteworthy class of men has special grounds for giving particular thanks to the stage. Only here do the world’s mighty men hear what they never or rarely hear elsewhere: Truth. And here they see what they never or rarely see: Man.

Thus is the great and varied service done to our moral culture by the better-developed stage; the full enlightenment of our intellect is no less indebted to it. Here, in this lofty sphere, the great mind, the fiery patriot first discovers how he can fully wield its powers.

Such a person lets all previous generations pass in review, weighing nation against nation, century against century, and finds how slavishly the great majority of the people are ever languishing in the chains of prejudice and opinion, which eternally foil their strivings for happiness; he finds that the pure radiance of truth illumines only a few isolated minds, who probably had to purchase that small gain at the cost of a lifetime’s labors. ...

The theater is the common channel through which the light of wisdom streams down from the thoughtful, better part of society, spreading thence in mild beams throughout the entire state. More correct notions, more refined precepts, purer emotions flow from here into the veins of the population; the clouds of barbarism and gloomy superstition disperse; night yields to triumphant light. (Vol. I, p. 216)

Speaker G:

But its sphere of influence is greater still. The stage is, more than any other public institution, a school of practical wisdom, a guide to our daily lives, an infallible key to the most secret accesses of the human soul. (Vol. I, p. 214)

EIRNS/Stuart Lewis

Confrontation between Mary and Elizabeth, “Mary Stuart,” November 1998, Reston, Virginia.The theater sheds light not only on man and his character, but also on his destiny, and teaches us the great art of facing it bravely. ... We have already come a long way, if the inevitable does not catch us wholly unprepared, if our courage and resourcefulness have already been tested by similar events, and our heart has been hardened for its blow.

The stage brings before us a rich array of human woes. It artfully involves us in the troubles of others, and rewards us for this momentary pain with tears of delight and a splendid increase in our courage and experience. In its company, we follow the forsaken Ariadne through echoing Naxos; we descend into Ugolino’s tower of starvation; we ascend the frightful scaffold, and witness the solemn hour of death. ... [N]ow that he must die, the intimidated Moor finally drops his treacherous sophistry. ...

But, not satisfied with merely acquainting us with the fates of mankind, the stage also teaches us to be more just toward the victim of misfortune, and to judge him more leniently. For, only once we can plumb the depths of his tormented soul, are we entitled to pass judgment on him. (Vol. I, p. 215)

First Speaker: Gotthold Lessing had already developed this idea, that in great Classical drama we can practice our emotions, as it were, in a playful manner, and thus we are then prepared in actual life, when we are forced to make sudden decisions which would otherwise strike us unprepared. And Schiller had the following to say about it:

Speaker G:

The pathetic is an artificial misfortune, and like the true misfortune, it places us in direct contact with the spiritual law that rules in our bosom. However, true misfortune selects its man and its time not always well: it often surprises us defenseless and, what is even worse, it often makes us defenseless. The artificial misfortune of the pathetic, on the contrary, finds us in full armament, and because it is merely imagined, so the independent principle in our soul gains room, to assert its absolute independence. ... The pathetic, one can therefore say, is an inoculation against unavoidable fate, whereby it deprives it of its malignancy, and the assult of the same is led to the strong side of man.

Therefore, away with the false understanding forebearance and the careless, overindulged taste, which throws a veil over the earnest face of necessity and, in order to place itself in the favor of the senses, invents a harmony between well-being and good conduct, of which no traces appear in the real world. Let evil destiny show itself to us face to face. Not in the ignorance of the danger surrounding us—for this must ultimately cease—only in the acquaintance with the same is there salvation for us. To this acquaintance we are now helped by the terrible, glorious spectacle of all destructive and again creative and again destructive alteration—of the now slowly undermining, now swiftly invading ruin, we are helped by the pathetical portraits of humanity wrestling with fate, of the irresistible flight of good fortune, of deceived security, of triumphant injustice, and of defeated innocence, which history establishes in ample measure and the tragic art through imitation brings before our eyes.

For where were those who, with a not entirely neglected moral predisposition, can read of the tenacious and yet futile fight of Mithridates, of the collapse of the cities of Syracuse and Carthage, and can dwell on such scenes, without paying homage to the earnest law of necessity with a shudder, momentarily reining in his desires and, affected by this eternal unfaithfulness of everything sensuous, striving in his bosom after the persevering? The ability to feel the sublime is therefore one of the most glorious predispositions in the nature of man, which, both because of its origin from the independent capacity of thinking and of the will, deserves our attention, and also because of its influence upon moral man, deserves the most perfect development.

The beautiful is merely well-deserved of man, the sublime of the pure demon in him; and because it is once our determination, even in all sensuous limitations to conform to the law book of the pure mind, so must the sublime be added to the beautiful, in order to make the aesthetical education a complete whole and to enlarge the sensibility of the human heart to the entire extent of our determination, and therefore also beyond the world of sense. (“On the Sublime,” Vol. III, pp. 268-269)

Youth: So, Beauty and the sublime must come together. And that should occur in art?

Speaker D: Of course, in art, as Schiller understands it:

EIRNS/Stuarts Lewis

Confrontation between Mary and Elizabeth, “Mary Stuart,” November 1998, Reston, Virginia.True art, however, does not aim merely at a temporary play; it seriously intends not to transpose a person into a merely momentary dream of freedom, but to make him really and in fact free, and to accomplish this by awakening in him a force, exercising it and developing it, to thrust the sensuous world, which otherwise only presses upon us as crude material, bearing down upon us as a blind power, into an objective distance, to transpose it into a free work of our mind, and to achieve mastery over the material with ideas. (“On the Employment of the Chorus in Tragedy,” Vol. IV, p. 309)

Young Girl: That’s it: Rule the material through ideas!

Speaker A: Schiller had in general the most beautiful image of man, and a clear idea of the meaning of life. In the “Aesthetical Letters,” he develops the idea of the individual and the state, similar to the way he develops it in “Lycurgus and Solon”:

Every individual man, one can say, carries by predisposition and destiny, a purely ideal man within himself, to agree with whose immutable unity in all his alterations is the great task of his existence. This pure man, who gives himself to be recognized more or less distinctly in every subject, is represented through the state; the objective and as it were canonical form, in which the multiplicity of the subjects strives to unite itself. Now, however, let two different ways be considered, how the man in time can coincide with the man in the idea, hence just as many, how the state can maintain itself in the individual, either thereby, that the pure man suppresses the empirical, that the state abolishes the individual; or thereby, that the individual becomes the state, that the man of time ennobles himself to the man in the idea. (Vol I, p. 228)

First Speaker: That is the same idea, of which Posa speaks in his dialogue with King Philip: “Be a King of a million kings!” If each man develops his full potential, then there is an inner harmony on the highest level! But that also requires, that an ever greater part of the population doesn’t remain on the lower level of purely sensuous experience, but rather, learns to feel and think sublimely.

Youth: And what’s that—to feel and think sublimely?

Speaker E:

Our intelligible self, that in us, which is not nature, must then distinguish itself from the sensuous part of our being and must become conscious of its self-reliance, its independence from everything, which can affect the physical nature, in short, its freedom.

This freedom is, however, by all means only moral, not physical. Not through our natural powers, not through our understanding, not as sensuous beings, may we feel ourselves superior to fearsome objects; for then our safety would always depend upon physical, thus empirical causes and therefore always remain dependent upon nature. Rather it must be completely indifferent, how we as sensuous beings fare thereby and our freedom must merely consist in that we do not at all hold our physical condition, which can be determined through nature, to be our self, but rather as something regarded as external and foreign, which has no influence on our moral person.

Great is he, who overcomes what is fearsome. Sublime is he, who even as he himself perishes, does not fear it. (“Of the Sublime”)

Youth: I imagine that that’s rather difficult. How does one achieve it—only by going to the theater?

First Speaker: Besides great historical drama, it is also the study of universal history itself, which helps a person succeed in transcending the narrowness of his physical existence. It helps him to find his identity in immortality. Schiller said that to his students in his address on “Universal History”:

Speaker C:

Even that we found ourselves together here at this moment, found ourselves together with this degree of national culture, with this language these manners, these civil benefits, this degree of freedom of conscience, is the result perhaps of all previous events in the world: The entirety of world history, at least, were necessary to explain this single moment. For us to have met here as Christians, this religion had to be prepared by countless revolutions, had to go forth from Judaism, had to have found the Roman state exactly as it found it, to spread in a rapid and victorious course over the world, and to ascend finally even the throne of the Caesars. Our raw forefathers in the Thuringian forests had to have been defeated by the superior strength of the Franks in order to adopt their religion. Through its own increasing wealth, through the ignorance of the people, and through the weakness of their rulers, the clergy had to have been tempted and favored to misuse its reputation, and to transform its silent power over the conscience into a secular sword. (Vol. II, pp. 263-264)

Speaker B:

EIRNS/Samuel P. Dixon

Scene from “William Tell,” LYM cadre school, San Bernadino, California, July 2001.For us to have assembled here as Protestant Christians, the hierarchy had to have poured out all its atrocities upon the human species in a Gregory and Innocent, so that the rampant depravity of moral standards and the crying scandal of spiritual despotism could embolden an intrepid Augustinian monk to give the signal for the revolt, and to snatch half of Europe away from the Roman hierarchy. For this to have happened, the weapons of our princes had to wrest a religious peace from Charles V; a Gustavus Adolphus had to have avenged the breach of this peace, and establish a new universal peace for centuries. Cities in Italy and Germany had to have risen up to open their gates to industry, break the chains of serfdom, wrest the scepter out of the hands of ignorant tyrants, and gain respect for themselves through a militant Hanseatic League, in order that trade and commerce should flourish, and superfluity to have called forth the arts of joy, so that the nation should have honored the useful husbandman, and a long-lasting happiness for mankind should have ripened in the beneficient middle class, the creator of our entire culture. (Vol. II, p. 264)

Speaker C:

For our mind to have wrested itself free of the ignorance in which spiritual and secular compulsion held it enchained, the long-suppressed germ of scholarship had to have burst forth again among its most enraged persecutors, and an Al Mamun had to have paid the spoils to the sciences, which an Omar had extorted from them. The unbearable misery of barbarism had to have driven our ancestors forth from the bloody judgments of God and into human courts of law, devastating plagues had to have called medicine run astray back to the study of nature ... . The depressed spirit of the Nordic barbarian had to have uplifted itself to Greek and Roman models, and erudition had to have concluded an alliance with the Muses and Graces, should it ever find a way to the heart and deserve the name of sculptor of man.— But, had Greece given birth to a Thucydides, a Plato, an Aristotle, had Rome given birth to a Horace, a Cicero, a Virgil and Livy, were these two nations not to have ascended to those heights of political wealth to which they indeed attained? In a word, if their entire history had not preceded them? (Vol. II, pp. 264-265)

Speaker B:

How many inventions, discoveries, state and church revoutions had to conspire to lend growth and dissemination to these new, still tender sprouts of science and art! How many wars had to be waged, how many alliances concluded, sundered, and become newly concluded to finally bring Europe to the principle of peace, which alone grants nations, as well as their citizens, to direct their attention to themselves, and to join their energies to a reasonable purpose!

Even in the most everyday activities of civil life, we cannot avoid becoming indebted to centuries past; the most diverse periods of mankind contribute to our culture in the same way as the most remote regions of the world contgribute to our luxury. The clothes we wear, the spices in our food, and the price for which we buy them, many of our strongest medicines, and also many new tools of our destruciton—do they not presuppose a Columbus who discovered America, a Vasco da Gama who circumnavigate the tip of Africa?

There is thus a long chain of events pulling us from the present moment aloft toward the beginning of the human species, the which intertwine as cause and effect. (Vol. II, p. 265)

Young Girl: So, there existed long ago a dialogue of cultures in universal history!

Speaker C:

All preceding ages, without knowing it or aiming at it, have striven to bring about our human century. Ours are all the treasures which diligence and genius, reason and experience, have finally brought home in the long age of the world. Only from history will you learn to set a value on the goods from which habit and unchallenged possession so easily deprive our gratitude; priceless, precious goods, upon which the blood of the best and the most noble clings, goods which had to be won by the hard work of so many generations!

And who among you, in whom a bright spirit is conjugated with a feeling heart, could bear this high obligation in mind, without a silent wish being aroused in him to pay that debt to coming generations which he can no longe discharge to those past? A noble desire must glow in us to also make a contribution out of our means to this rich bequest of truth, morality, and freedom which we received from the world past, and which we must surrender once more, richly enlarged, to the world to come, and in this eternal chain which winds itself through all human generations, to make firm our ephemeral existence.

However different the destinies may be which await you in society, all of you can contribute something to this! A path toward immortality has been opened up to every achievement, to the true immortality, I mean, where the deed lives and rushes onward, even if the name of the author should remain behind. (“Universal History,” Vol. II, pp. 271-272)

Youth: Okay, the idea of universal history is clear. But how did Schiller understand freedom?

First Speaker: Only he who casts from himself the “fear of the earthly,” only he who believes in universal principles, which transcend the narrow dimension of his own life—and therefore is sublime—is actually free. Schiller gained confidence that this were possible, from his profound conviction that the cosmic order is subject to the same lawfulness as the human soul.

Speaker F:Young Girl: But, how does one become a genius, a man of genius?The universe is a thought of God. After this ideal mental image stepped over into reality ... [it] is the vocation of all thinking beings, to find once again the first design in this existing whole, to seek out the rule in the machine, the unity in the composition, the law in the phenomenon and to pass backward from the structure to its founding design. Therefore, for me there is a single appearance in nature, the thinking Being. (“Philosophical Letters: Theosophy of Julius,” Vol. III, p. 206)

EIRNS/Stuart Lewis

LYM east coast chorus, ICLC/Schiller Institute conference, Reston, VA, February 2003.Harmony, truth, order, beauty, excellence give me joy, because they place me into the active condition of their inventor, of their possessor, because they betray to me the presence of a rational, feeling Being, and let me divine my relationship with this Being. A new experience in this realm of truth, gravitation, the discovered circulation of the blood, the natural system of Linnaeus, signify to me ... only the reflection of one spirit, a new acquaintance with a being similar to me. I confer with the infinite through the instrument of nature, through the history of the the world—I read the soul of the Artist in his Apollo. (Vol. III, p. 207)

Speaker E: That is the same idea, as in the poem, “Columbus”!

Steer, courageous sailor! Although the wit may deride you,

And the skipper at th’ helm lower his indolent hand—

Ever, ever to th’ West! There must the coast be appearing,

Lies it yet clearly and lies shimm’ring before your mind’s eye.

Trust in the guiding God and follow the silent ocean,

Were it not yet, it would climb now from the billows aloft.

With Genius stands nature in everlasting union,

What is promised by th’ one, surely the other fulfills.

First Speaker: In fact, only a person can think thus, who has educated his emotions up to the level of reason. And that is Agape, love. Schiller was still quite young, when he developed this thought:

Speaker F:

Youth: Who, then, is Raphael?Now, best Raphael, let me look around. The height has been scaled, the fog has fallen, as in a blossoming landscape I stand in the midst of the immeasurable. A purer sunlight has refined all my concepts.

Love therefore—the most beautiful phenomenon in the soul-filled creation, the omnipotent magnet in the spiritual world, the source of devotion and of the most sublime virtue—Love is only the reflection of this single original power, an attraction of the excellent, grounded upon an instantaneous exchange of the personality, a confusion of the beings.

When I hate, so take I something from myself; when I love, so become I so much the richer, by what I love. Forgiveness is the recovery of an alienated property—hatred of man a prolonged suicide; egoism the highest poverty of a created being.

When Raphael stole away from my last embrace, my soul was torn apart, and I cry at the loss of my more beautiful half. (Vol. III, pp. 210-211)

First Speaker: Raphael is the friend, to whom Schiller directed his “Philosophical Letters.” Listen further; the most important thing comes first:

But love has brought forth effects, which seem to contradict its nature.

It is thinkable, that I enlarge mine own happiness through a sacrifice, which I offer for the happiness of others—but also then, when this sacrifice is my life? And history has examples of such sacrifice—and I feel it lively, that it should cost me nothing, to die for Raphael’s deliverance. How is it possible, that we regard death as a means to enlarge the sum of our enjoyments? How can the cessation of my existence agree with the enrichment of my being?

The assumption of an immortality lifts this contradiction—but it also distorts forever the high gracefulness of this appearance. Consideration of a rewarding future excludes love. There must be a virtue, which suffices even without the belief in immortality, which effects the same sacrifice even at the danger of annihilation.

It is indeed ennobling to the human soul, to sacrifice the present advantage for the eternal—it is the noblest degree of egoism,—but egoism and love separate mankind into two highly dissimilar races, whose boundaries never flow into one another. Egoism erects its center in itself; love plants it outside of itself in the axis of the eternal whole. Love aims at unity, egoism is solitude. Love is the co-governing citizen of a blossoming free state, egoism a despot in a ravaged creation. Egoism sows for gratitude, love for ingratitude. Loves gives, egoism lends—regardless in front of the throne of the judging truth, whether for the enjoyment of the next-following moment, or with the view toward a martyr’s crown—regardless, whether the tributes fall in this life or in the other!

Think thee of a truth, my Raphael, which benefits the whole human species into distant centuries—add thereto, this truth condemns its confessor to death, this truth can only be proven, only be believed, if he dies. Think thee then of the man with the bright, encompassing, sunny look of genius, with the flaming wheel of enthusiasm, with the wholly sublime predisposition to love. Let the complete ideal of this great effect climb aloft in his soul—let pass to him in a faint presentiment all the happy ones, whom he shall create—let the present and the future press together at the same time in his spirit—and now answer thee, does this man require the assignment to an other life?

The sum of all these perceptions will become confused with his personality, will flow together into one with his I. The human species, of which he now thinks, is he himself. It is one body, in which his life, forgotten and dispensible, swims like a drop of blood—how quickly will he shed it for his health! (Vol. III, pp. 213-14)

Young Girl: How old was Schiller when he wrote that?First Speaker: He was just twenty years old. And he had already achieved the level of the sublime, when a man identifies himself with the fate of mankind.

Speaker A: Later, in his Classical period, Schiller expressed this same thought:

Youth:: What was it Goethe said when Schiller had just died? “For he was ours!” And what do we young people say today? Schiller’s ideas are the over-all best that we can find in German culture and history. And therefore we say: “He is ours.”We call it a beautiful soul, when moral sentiment has assured itself of all emotions of a person ultimately to that degree, that it may abandon the guidance of the will to emotions, and never run danger of being in contradition with its own decisions. Hence, in a beautiful soul individual deeds are not properly moral, rather, the entire character is. ... With such ease, as if mere instinct were acting out of it, it carries out the most painful duties of humanity, and the most heroic sacrifice which it exacts from natural impulse comes to view like a voluntary effect of just this impulse. Hence, the beautiful soul knows nothing of the beauty of its deeds, and it no longer occurs to it, that one could act or feel differently; a trained student of moral rules, on the other hand, just as the word of the master requires of him, will be prepared at every moment to give the strictest account of the relationship of his action to the law. His life will be like a drawing, where one sees the rules marked by harsh strokes, such as, at best, an apprentice of the principles of art might learn. But in a beautiful life, as in a painting by Titian, all of those cutting border lines have vanished, and yet the whole form issues forth the more true, vital and harmonious.

It is thus in a beautiful soul, that sensuousness and reason, duty and inclination harmonize, and grace is its epiphany. (“On Grace and Dignity,” Vol II, p. 368)

* * *

| The following poems should be recited by Youth:: “Words of Faith” (Vol. I), “Breadth and Depth” (Vol. I), “Words of Delusion” (Vol. I), “Longing” (Vol. III), “The Maid of Orleans” (Vol. I), “The Pledge” (Vol. IV). |

Related pages: