Voyage to a Culture of Discovery

by Karel Vereycken

March 2016

A fast and superficial reading of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s (1749–1832) poem “Meeresstille” (“Calm Sea”) could lead us rapidly to an impression of quiet dullness. Yet immediately, as early as the third line, the apparent serenity (Deep calmness reigns over the waters, / Without motion rests the sea,), will be accompanied by a growing anxiety opposing it. (And, worried, the sailor observes / The flat surface that encircles him.)

Franz Schubert. |

This anxiety will develop into real panic dominating the second verse, when the isolated seafarer on his ship dares to confront, in his mind, the horrible consequences of the absence of movement that looms behind a silence that becomes increasingly unbearable (No breeze, from any quarter! / Mortal silence, awfully! / In this unheard vastness / No wave stirs.) This deadly frightening silence announces a terrible event to come. In effect, if the wind doesn’t show up, his ship is doomed! And soon, the lack of supplies in this prison of loneliness will bring a not uncertain death to the seaman.

On June 21, 1815, Franz Schubert (1797–1828), composed a beautiful Lied (D 216) based on this poem, a song he asks us to perform “Sehr langsam, ängstlich” [very slowly, with anxiety].

While the idea of calm reposing water is recreated in a succession of accords played with arpeggios, the constant increase of dissonances, by adding flats and sharps, brings powerfully alive a permanent worrisome instability. The choice of a “barred C” for time signature (so-called cut time, two half notes per measure), added to the already very slow tempo, substantially increases the desired effect of uneasiness.

Schiller’s Sublime

creative commons

The monument to poets Wolfgang Goethe and Friedrich Schiller in Weimar, Germany. |

The idea that one can use elements such as silence and solitude—for they possess a poetical power, although considered of minor dimension, useful as transitions to the sublime—is the fruit of the passionate research born of the correspondence between Goethe and the philosopher-dramatist Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805). The latter mentions these themes in his Of the Sublime, published in 1802, where he evokes this naturerhabene (sublime resulting from nature):

“A deep stillness, a great void, a sudden illumination of darkness, [these] are in and of themselves very indifferent things, that distinguish themselves through nothing but the extraordinary and unusual. Nevertheless they excite a feeling of terror, or at least intensify an impression of [the] same, and are consequently suitable for the sublime.”

(…) “When Virgil wants to fill us with dread over the realm of Hell, he makes us exquisitely aware of the emptiness and stillness of [the] same.”

(…)“With the initiation into the mysteries of the ancients, especially great store was set by a frightful solemn impression, and to that end one also availed oneself especially of silence. A deep stillness gives the power of imagination free latitude, and raises the expectations of something frightful to come. With the practice of devotion the silence of an entire assembly is a very effective means, to give vitality to fantasy and put the heart in solemn spirits. Folk-superstition itself makes use of the reveries thereof, for as everyone knows, a deep stillness must be observed, when one has a treasure to exalt. In the enchanted palaces, that are found in fairytales, a deathly silence reigns, that arouses dread, and it belongs to the natural history of the enchanted woods, that nothing living stirs therein. Also solitude is something frightful as soon as it is sustained and involuntary, like, for example, an exile to an uninhabited island. A vast expanse of desert, a lonely, many-miles-long forest, wandering astray on the boundless sea, are clear conceptions, which evoke dread, and may be employed in poetry toward the sublime.

But here (with solitude) this is nonetheless already an objective basis for fear, because the idea of great solitude carries with it the idea of helplessness as well.”

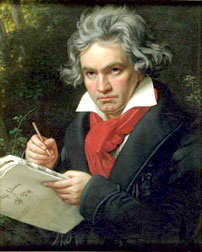

Ludwig van Beethoven and Scientific Discovery

After Schubert, it was another reader of Schiller who felt challenged by the poem: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827). He would exploit for his composition another poem, Glückliche fahrt [Prosperous voyage], a poem that Goethe wrote right after his Meeresstille. Beethoven unites them in a short cantata for chorus and orchestra (Opus 112), also composed in the same year, 1815.

In this second poem, Goethe called upon his reading of Homer’s Odysseus. During his numerous travels, Ulysses lands on the island of Eolia (Chant X, 1-33), named after the God that reigns on the island. Aeolus is the god of winds who warmly welcomes Ulysses. After a stay of a month, Ulysses thinks about traveling home. Aeolus offers him a wine skin in which are enclosed all the unfavorable winds. The remaining free winds fill the sails of Ulysses’ ship and steer him into the right direction to travel home. But while Ulysses sleeps, his companions risk opening the wine skin. All the winds rush out, provoking a tempest that throws Ulysses’s ship back on the island. Goethe’s poem: The mist is pulled aside / The sky lights up / And Aeolus undoes / The ties of fear.

By adding the remaining part of the poem, Goethe transforms the two poems into a single metaphor of the creative process taking place in the human mind, proceeding from the process of hypothesis formation to the act of discovery, a process Lyndon LaRouche sometimes qualifies as a “creative agony.”

Indeed, the situation of a helpless sailor lost on the surface of the ocean can be easily compared to that of a scientist who realizes the grave inconsistencies of “his system”, but without disposing of enough new knowledge capable of offering a better, less imperfect, explanation.

That creative state of mind provokes necessarily a strong feeling of anxiety and despair, since the exhaustion of a long series of hypothesis and successive unfruitful experiences lead us to the painful conclusion that our knowledge, held to be so valuable up till now, is entirely worthless! “Our system” is dead, it’s gone!

In Goethe’s poem Glückliche Fahrt, Aeolus unleashes the winds: There, the winds rustle, / There, the sailor moves on/, since after this present from heaven (a powerful wind arrives), it is now up to the sailor to seize this historical opportunity: Hurry! Hurry/ The waves are breaking. /The distant becomes nearby, /Already, I see the land! In this way, in just a few seconds, the “light goes on” in the head of the discoverer, he knows who he is, he “sees” where he has to go, and he realizes what he can do to get there.

Beethoven, an optimistic republican and militant of the American Revolution, could not but be charmed by this poetical material.

Ludwig van Beethoven. |

At the start, to dramatize the worrying aspect, the composer will introduce very strong nuances. One hears a forte on No breeze, from any quarter! [Keine Luft von Keiner Seite!]; and on In this unheard vastness [ungeheueren Weite]. Or a pianissimo on Todesstille fürchterlich! [Mortal silence, awfully!].

Although the initial architecture of Beethoven’s composition seems quite similar to that of Schubert, in Beethoven’s piece the vertical accords, by a gradual displacement of the theme, introduce a slowly growing apotheosis towards the very idea of movement itself. That displacement will deploy all its richness when the theme becomes the subject of the exchanges between the different voices (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass) or groups of voices, either in the form of a dialogue or developed in a canonical form. Then, with great talent, the liberating concept of movement arises from within the poetical text itself: it emanates as a wave from precisely the word Welle [wave] to lead us to a tempest of sounds when the mists disappear at the beginning of the second poem Glückliche Fahrt. There, by shifting the tempo to 6/8 (six notes during two beats per measure), the orchestra starts “jumping up and down the walls” of the scale, running in diametrically opposed directions, provoking a tremendous sense of movement. The powerful entrance of the voices announcing the discovery of land at the horizon, evokes Columbus's discovery of the new world. The rest is nothing but the celebration of that joyful event and installs us definitely into a “new geometry.”

One has to be pretty foolish to believe it is sufficient to understand the phraseology and the metrics of a poem to transpose it into music, although its comprehension is vital to identify the composer’s sources of inspiration. The latter chooses, with rigorous freedom, the best material for his task, as does the sculptor when he chooses a bloc of marble in the quarry.

In a letter to his pupil Czerny in 1809, Beethoven said that “Schiller’s poems are very difficult to set to music. The composer must be able to lift himself far above the poet; who can do that, in the case of Schiller? In this respect, Goethe is much easier.”

We know otherwise that Goethe didn’t appreciate those composers giving a supplementary dimension to his poems. Neglecting Schubert and Beethoven, Goethe preferred composers such as Reichardt and others, precisely because they limited themselves to transcribing his poems to music without “adding” another dimension to “his” sublime.

Beethoven, as stated in his letter to Rochlitz in 1822, nevertheless greatly adored the works of the poet he met in 1812: “Goethe—he is alive, and he wants us all to live with him. That is why he can be set to music. There is no one who lends himself to musical setting as well as he.”

Always ironical, Beethoven, seeing that Goethe took a little bit too much pleasure at shining at the courts, sent him his Meeresstille und Glückliche Fahrt stating that “because of their opposing moods, these two poems lend themselves to the expression of contrast in music. I would be happy to know if I’ve unified in the appropriate fashion my harmony with yours.”

Useful to work with:

CD : Schubert, Lieder nach gedichten von Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Christoph Prégardien (tenor), Andreas Staier (piano), Deutsche Harmonia Mundi, BMG Classics.

Audio : Ludwig van Beethoven, Meerestille und glückliche Fahrt, op. 112, Wiener Philharmoniker, Claudio Abbado, 1988, Deutsche Grammofon, Polydor International.

Books : A Manual on the rudiments of Tuning and Registration. Book I, Introduction and Human Singing Voice, Schiller Institute, 1992, Washington.

Internet : Friedrich Schiller, Of the Sublime

Poems by Goethe

Translated by Karel Vereycken

Meeresstille Tiefe Stille herrscht in Wasser, Keine Luft von keiner Seite!

|

Calm Sea Deep calmness reigns over the waters, No breeze, from any quarter! |

Gluckliche Fahrt Die Nebel zerreisen, Es säuselst die Winde, Geschwinde! Geschwinde! |

Prosperous Voyage The mist is pulled aside, There, the winds rustle, Hurry! Hurry! |