Copley’s Portrait of Samuel Adams

by Steve Carr

October 2011

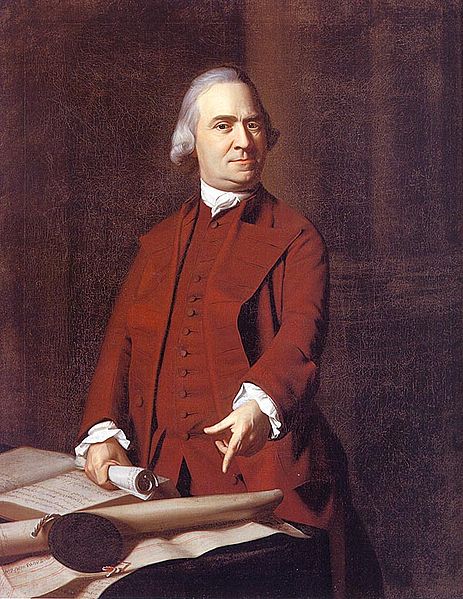

In this c. 1772 portrait by John Singleton Copley, Adams points at the Massachusetts Charter, which he viewed as a constitution that protected the peoples' rights. |

Copley’s portrait of Samuel Adams

John Singleton Copley 1738-1815

Samuel Adams 1722-1802

Portrait done c.1772

Samuel Adams wanted to be remembered not for his famous inflammatory, rabble-rousing speeches, but rather for his actions on the morning of March 6, 1770. This was the morning after the Boston Massacre, when Adams stormed into the office of the hated, ultra-Loyalist Governor Thomas Hutchinson to confront him with a list of demands including the end to military occupation of Boston. This he considered was his finest hour. However, it was not Adams who requested this portrait but rather John Hancock, who wanted this stormy scene of defiance and resolve to hang on his wall in his home. Hancock wanted it to inspire, persuade, (and perhaps also threaten) the leadership of the independence movement who frequently met in his living room.

The layout of this scene was designed to put the viewer in the same position as the Governor (across the table from Adams) in order to confront all who see it with this issue of injustice. This was a call to arms and in fact everyone of the period understood its urgent and stirring, yet discomforting message. The portrait was well known and was frequently copied on canvas and mass produced on political broadsides for propaganda purposes.

Copley tried to capture the volatile character of Adams who, with his slightly contorted body, is given more intensity in his commanding presence. Governor Hutchinson had long been fearful of Adams and knew that he was a man that was willing to fight and die for his country. Hutchinson called him, “the greatest incendiary in the King’s dominion.” It has been said that the governor’s knees began to tremble and his face grew pale--to the great enjoyment of Adams. This tense moment broke what would otherwise be the quiet, serene atmosphere of the governor’s office. Adams dominates the scene, and even though he is standing still, the room is filled with energy, as he crowds the table, clenching his right fist containing the list of demands, and pointing his left hand at the Massachusetts Bay Charter.

It is ironic that the British press attacked Samuel Adams for being a violent leader of a dangerous, unruly mob, but here Adams is seen alone (without his “mob”), insisting on enforcing the Charter, and to remove the British troops as the only way to stop the bloodshed.

Final Note

The Boston Massacre was sparked when a Boston merchant sent a young apprentice named Edward Gerrish to collect an unpaid bill from a British officer. When the officer refused to pay, and the young apprentice raised his voice at the officer, a British sentry, Private White, left his post at the customs house, and began to club the boy. The boy escaped the clubbing only to return later with other boys who began to throw snow, ice, and trash at Private White, the brutal British sentry. By the time the Officer of the Day arrived there was a mob of people who continued to throw things. The eight British troops on the scene opened fire killing five and wounding six. It is believed that the first American casualty in the American Revolution was Crispus Attucks, a young African-American who died on the scene. The funeral for the five victims and the services that followed at the Old South Church were the largest gatherings in North American history.