This Week in History

February 19-25, 1732:

General Washington Sets Up an Effective Intelligence Network, and Takes a Role Himself

February 2012

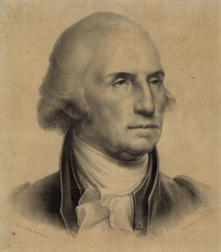

George Washington |

When General George Washington triumphantly led the Continental Army into New York City at the end of the American Revolution, he amazed many loyal Americans by breakfasting the very next morning with Hercules Mulligan, a known Tory. Not only that, but the General then visited James Rivington, publisher of the New York Gazette, a notorious Tory newspaper. Of course, both of these gentlemen had served as members of the patriot intelligence network, which owed its existence largely to the efforts of George Washington.

On this anniversary of Washington's birthday, February 22, 1732, it is worthwhile to look at how this republican intelligence network was established, and the very active role which George Washington took within it. In the early days of the American Revolution, the gathering of information was haphazard, and those attempting to gather it were untrained. The sad case of Captain Nathan Hale, sent behind British lines with no training or backup, illustrates the point.

However, the Americans were under the goad of grim necessity to develop an intelligence network, not only because their military forces were so outnumbered, but because they faced one of the most feared intelligence services in the world, that of the British Empire. The characteristic of that empire was corruption, and therefore its intelligence service, modelled on that of Venice, used various forms of corruption, including large amounts of gold, to attain its ends. Its Achilles' heel was its belief that anyone could be corrupted, and to that weakness was added the inability of many of its participants to out-think George Washington.

Portrait of Samuel Fraunces, unknown artist, circa 1770-1785, Fraunces Tavern Museum, New York City. |

Some progress had been made in setting up intelligence agents by 1776, when Washington was headquartered in New York City after driving the British out of Boston. In that year, a plot to kill or kidnap General Washington was discovered in the nick of time, partly due to the efforts of Samuel Fraunces, a free black who owned the famous Fraunces Tavern where British officers wined and dined during the war, and where Washington bade farewell to his officers when the erstwhile diners were forced to abandon the city. Also involved in protecting Washington was Samuel's 13-year-old daughter Phoebe, who detected part of the plot, in which one of Washington's own bodyguards was involved.

When the British captured New York City and the Continental Army was forced to retreat across New Jersey, Washington left an intelligence net behind him, one that helped lead to the victories at Trenton and Princeton. At each stop, a few army volunteers were dropped off to keep a close watch on the advancing British, but a much larger group of ordinary Americans was recruited to gather intelligence in their immediate neighborhoods. General Washington did some of the recruiting himself, and kept a tight hand on reports from the network.

He also insisted that the American intelligence agents be properly trained. "Give the persons you pitch upon, proper lessons," Washington told General Thomas Mifflin, who was about to set up an intelligence network in Philadelphia. Washington even drafted a paper in September of 1780 for the benefit of spies sent into New York, telling them what kind of signs to look for that would imply a possible British military move. These included whether the British were preparing wagons and shoeing their horses, whether the troop transports were taking on supplies, and even included the detail that if the Tory merchants were packing up or selling off their goods, the agent should "attend particularly to Coffin and Anderson who keep a large dry good Store and supply their Officers and Army."

Another reason that Washington wanted accurate assessments of British movements was that he would install American agents ahead of time in any city or town that the British were aiming to capture. This policy was followed so well in the months between finding out the British were moving to attack Philadelphia, and the actual British conquest of the city, that all of southeastern Pennsylvania had been seeded with a well-coordinated American spy ring before the British troops ever set foot on Market Street.

Washington loved the theater, and on some occasions he could not resist acting a part in deception operations. One of these opportunities came before the Battle of Trenton on Christmas Day in 1776, when many of the state enlistments for the Continental Army would expire with the turn of the New Year. Washington had to strike before his army was reduced to an impossibly small size, but he needed intelligence in order to use his forces wisely. He not only needed a victory, but one that would embolden those soldiers who were discouraged or wavering. If he made a mistake, the republican cause would be reduced to conducting guerrilla warfare.

Washington found a courageous agent in John Honeyman, a New Jersey weaver and butcher who had fought for the British during the French and Indian War, and had even helped to carry the mortally wounded General Wolfe off the Plains of Abraham at Quebec. Around the middle of December, Honeyman fled his home and pretended to espouse the British cause. Washington issued orders to arrest him on sight, but added the provision that he must be brought back alive. In the meantime, Honeyman travelled in and out of Trenton on business, supplying the Hessian troops with beef and gathering information on Colonel Rall's plans.

When he had gathered enough intelligence, Honeyman wandered far enough from Trenton to allow the Americans to capture him. He was brought to General Washington, who ordered the room cleared. After they had conferred, Washington loudly berated Honeyman for his treason, much to the delight of the Continental soldiers outside and to the great interest of any lurking Tory spies. Then prisoner Honeyman was put into a log hut to await his early morning court martial, but a fire broke out nearby, and when the sentries came back from putting it out, Honeyman was gone.

A few hours later, Honeyman was telling Colonel Rall in Trenton that "no danger was to be apprehended" from the American camp across the Delaware "for some time to come." Meanwhile, Washington had sent out three volunteers, although he had wanted more, to prevent any Tories from sending warnings to Colonel Rall about the coming American move across the Delaware. Because there were not enough men for the job, one Tory farmer did ride to Trenton with a written warning. But Rall was in the midst of Christmas festivities and refused to see him. When the farmer sent in the note, Rall put it in his pocket unread, and that is where it was found after he was mortally wounded during the Battle of Trenton.

After Washington's subsequent victory at Princeton, also aided by good intelligence, the British retreated back into New York City, and Washington established his headquarters at Morristown, New Jersey. When campaigning began again in 1777, General John Burgoyne and his large British force set out from Canada southward via Lakes Champlain and George, heading for the Hudson Valley. He was to link up with British forces from New York, which would move up the Hudson and thus cut the rebellious American colonies in two.

Washington consulted with General Philip Schuyler, who commanded at Albany, and they developed a master plan which eventually led to the American victory at Saratoga. Closer to his own headquarters, Washington had to deal with the knotty problem of what British Generals William Howe and Henry Clinton would do, especially in regard to the large British fleet anchored in New York Harbor. On July 23, the fleet put out to sea with Sir William Howe's troops on board, while Sir Henry Clinton remained in New York. Howe's destination was unknown, but Washington's networks had informed him that the target was Philadelphia. This was totally contrary to reason, since Howe and Clinton had been ordered by London to cooperate fully with Burgoyne, but British Generals tended to be jealous of each other's prerogatives and generally followed the maxim of "every man for himself."

Soon, a young man appeared at one of the American outposts above New York, saying that he'd been held as a prisoner in the city but had been given his liberty and supplied with money to enable him to carry a letter from Howe to Burgoyne. Washington examined the letter, and it was indeed in Howe's handwriting and was signed by him. It told Burgoyne that he was bound for the East to attack Boston, but was "now making demonstrations to the southward, which I think will have the full effect in carrying our plan into execution." Howe promised that he would support Burgoyne from his new base in New England.

Washington immediately recognized the letter as a deception. "No stronger proof could be given that Howe is not going to the eastward," he said. "The letter was evidently intended to fall into our hands. If there were not too great a risk of the dispersion of their fleet, I should think their putting to sea a mere manoeuvre to deceive, and the North River [Hudson River] still their object. I am persuaded, more than ever, that Philadelphia is the place of destination." Washington immediately prepared to march a large portion of his troops to Philadelphia, and his reasoning and intelligence reports proved correct.

It was not that Washington and his spymasters did not provide the British with letters actually written by Washington or his commanders but containing false information—they did. But Washington never allowed a false piece of information to arrive in just one way. He took care that the same information arrived at British Headquarters from many different sources in different parts of the country. He also did not fear sending the British actual information on his troop strength or the location of his supply depots (if the British could not reach them), as long as the message also contained one item of false information which the British would believe along with the rest. For example, in trying to keep General Clinton pinned down in New York while Washington moved his troops south to trap General Cornwallis on the Yorktown Peninsula, a wealth of real information was included with the fable that the Americans were gathering all the boats they could lay their hands on. This, and an American deception operation involving the building of baking ovens, laying out encampments, and moving a small number of troops down the east bank of the Hudson toward New York, convinced Clinton that an American attack was imminent.

Despite pleas for help from General Cornwallis, Clinton did not dare embark reinforcements for Virginia, when he might need them in New York. While Washington and his main body of troops were moving southward beyond the Watchung Mountains, a British intelligence agent sent Clinton a full description of American movements on a paper rolled up in a button. Clinton, unlike Rall, did read it, but he didn't believe it. The subsequent American victory at Yorktown led to the Peace of Paris, where Britain was forced to recognize the fact that America had become an independent nation.