This Week in History

December 1-7, 1782:

Benjamin Franklin Successfully Concludes

the American Revolution

December 2013

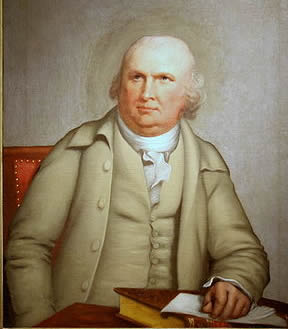

Benjamin Franklin.

|

On November 30, 1782, the American commissioners appointed by Congress to negotiate a peace settlement with Great Britain signed the preliminary treaty in Paris. The three commissioners—Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay—had all participated in the negotiations, but it was Franklin who had set the framework for the ultimate and happy result.

The news of the American and French victory at Yorktown in October of 1781 reached Paris on November 20, and the city burst into celebrations. But the path to a peace treaty was long and frustrating. King George III was not about to break up the British Empire, and he absolutely refused to recognize American independence. He also made it very clear that there was one person who was responsible for his uncomfortable predicament.

The king wrote to Lord Shelburne: "I am sorry to say it but from the beginning of the American troubles to the retreat of Mr. Fox, this country has not taken any but precipitate steps whilst caution and system have been those of Dr. Franklin, which is explanation enough of the causes of the present difference of situation." King George did everything he could to hinder the peace negotiations and insisted that the American "Loyalists" be compensated by America for their losses. He eventually yielded on recognizing America's independence, by authorizing his envoy to deal with the "United States." But when the desired concessions on compensating the Loyalists did not materialize, His Majesty threatened to retire to Hanover as a sign of his displeasure.

The American side was also beset with difficulties. Congress had authorized five peace commissioners in June of 1781, even before the victory at Yorktown. Of them, two, Thomas Jefferson and Henry Laurens did not serve; and with Adams in Holland negotiating a loan, and Jay employed in diplomacy in Madrid, Franklin had to handle the first part of the negotiations alone. The Americans had to deal with changes in policy and envoys from four succeeding British ministries—those of Lord North, Lord Rockingham, Lord Shelburne, and Charles James Fox.

Naval Historical Center, Washington, D.C.

A painting of President John Adams (1735-1826), 2nd president of the United States, by Asher B. Durand (1767-1845).

|

Before the news of Yorktown arrived, an aging and ill Benjamin Franklin had written Congress that he wished to be relieved of his commission as envoy to France. When he received the appointment to the peace commission, he agreed to remain in France, but he warned John Adams that, "I have never known a peace made, even the most advantageous, that was not censured as inadequate, and the makers condemned as injudicious or corrupt. Blessed are the peace makers is, I suppose, to be understood in the other world, for in this they are frequently cursed."

Congress had instructed the peace commissioners to stipulate that America had two non-negotiable conditions. These were: an acknowledgment by Britain of America's independence, and the continuation of America's treaty with France. After the victory at Yorktown, Franklin thought America could do even better. But his work was made more difficult by an anti-French faction in America, delightedly encouraged by the British and led by Arthur Lee, that accused Franklin of being too pro-French. Even Adams and Jay held milder versions of this view, but ended up admitting that Franklin had done well by America in the treaty.

Robert Morris, portrait by Robert Edge Pine (c. 1720-1788).

|

Robert Morris, who had bankrupted himself by supporting the American cause and its currency, wrote to Franklin warning him about the faction which was slandering him. Franklin replied that he was extremely sorry to hear of the attacks on France, as it tended to hurt "the good understanding" which existed between the two governments. "There seems to be a party with you that wish to destroy it," wrote Franklin. "If they could succeed, they would do us irreparable injury. It is our firm connection with France that gives us weight with England, and respect throughout Europe. If we were to break our faith with this nation, on whatever pretence, England would again trample on us, and every other nation despise us."

Indeed, England was at that moment, in the person of Lord Shelburne, plotting to do just that, by driving a wedge between America and France. Richard Oswald, the envoy to the Paris negotiations and a close friend of Lord Shelburne, was instructed to see how far apart he could pull the two governments. Oswald told Franklin that once the issue of American independence was settled, reconciliation with Britain could occur quickly. Franklin, not to be manipulated, replied that the issue of independence was already settled, and had been since 1776, and if the British desired reconciliation they must recognize that it was more than "a pretty phrase."

Franklin then played an unsettling card. He suggested that the Americans might want to ask for reparations for the towns and farms that the British and Hessians had burned. This would amount to a very large sum, but this difficulty could be overcome by Britain magnanimously ceding Canada to the United States, since the price of the furs gained from that colony probably did not compensate Britain for the expense of governing her. At any rate, this would solve two problems at one stroke, for the new land could serve as reparation for the displaced Americans, and the money from the sale of the lands to other Americans could be used to compensate the "Loyalists" for their losses.

This stunning proposal was duly forwarded to Shelburne, but there is no record of his reaction. Shelburne, of course, usually received early intelligence of Franklin's proposals and dealings with French Foreign Minister Vergennes from his many spies, one of whom, Edward Bancroft, was a trusted aide to the American commissioners. When a supporter of the American cause wrote to Franklin warning him that he was surrounded by spies, he replied that "As it is impossible to discover in every case the falsity of pretended friends who would know our affairs; and more so to prevent being watched by spies, when interested people may think proper to place them for that purpose, I have long observed one rule which prevents any inconveniences from such practices.

"It is simply this: to be concerned in no affairs that I should blush to have made public," Franklin continued, "and to do nothing but what spies may see and welcome. When a man's actions are just and honourable, the more they are known, the more his reputation is increased and established. If I was sure, therefore, that my valet de place was a spy, as he probably is, I think I should probably not discharge him for that, if in other respects I liked him."

Franklin and Vergennes were well aware of the British attempt to separate them, and in meetings they agreed to coordinate their peace efforts. Franklin suggested that Britain's strategy might be to conclude separate treaties with the four nations that had been fighting her in order to isolate one of them as a future target. He then recommended that all four countries—the other two being Spain and Holland—enter into a new treaty among themselves, pledging mutual defense in case of a British attack upon one of them. Vergennes agreed, but was noncommittal as to whether this could be carried through.

In the early fall of 1782, Vergennes informed Franklin that King Louis XVI agreed that the Americans should negotiate a separate treaty with Britain as long as the treaties of all four nations went hand-in-hand and were signed on the same day. Franklin had already made sure that the British government had acknowledged American independence before the start of formal negotiations, so that the British could not regard independence as a concession which would require a quid pro quo from the Americans.

Franklin gave Richard Oswald two lists—one of points which were "necessary" to a peace treaty, and one of "advisable" elements. The first two necessary points were American independence and the evacuation of all British troops from American soil. The next was a definitive determination of the borders of the United States, and the restoration of the boundaries of Canada to what they had been before the Quebec Act of 1774.

In that act, which was part of British reprisals for the Boston Tea Party, the boundary of Canada had been moved southward from the Great Lakes down to the Ohio River, in order to trap the American colonies east of the mountains. Moving the Canadian border northward extended America's western boundary to the Mississippi River. The final necessary point consisted of British recognition of the American right, which had been exercised for hundreds of years, to fish on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

For his "advisable" points, Franklin included reparations to Americans ruined by the burning of towns and farms, public acknowledgement by Britain of its error in prosecuting the war, open commercial relations between America and Britain, and the ceding of Canada to the United States. Lord Shelburne agreed to Franklin's necessary items on the condition that the advisable ones be dropped.

When Charles James Fox replaced Shelburne as Prime Minister, he favored opening British commerce to America in order to wean her from France, but King George was again adamantly opposed. As a result, after the peace treaty was signed, Britain dumped her manufactured goods in America below cost, in order to undercut and destroy any nascent American industry. Britain also instituted a policy of technological apartheid against the United States, hoping to prevent its industrialization. However, once the treaty was signed, the foreign ministers of Sweden, Denmark, Portugal, and Prussia arrived at Franklin's home in Passy to negotiate commercial treaties with America.

The preliminary treaty with Great Britain, containing all of Franklin's "necessary" articles, was signed by the American commissioners on November 30, 1782, and France and Spain signed their preliminary articles on January 20 of 1783. The Netherlands' treaty was delayed until September 2, so the official Treaty of Paris, with all the signatories, was not issued until the next day.

In May of 1784, after Congress had ratified the treaty, Benjamin Franklin wrote to Charles Thomson, the Secretary of Congress, that "the great and hazardous enterprise we have been engaged in is, God be praised, happily completed, an event I hardly expected I should live to see." He then wrote that peace would quickly restore the country if Americans kept their faith. If they failed, the vultures of the world, especially the British, would be waiting. "If we do not convince the world that we are a nation to be depended on for fidelity in treaties, if we appear negligent in paying our debts, and ungrateful to those who have served and befriended us, our reputation, and all the strength it is capable of procuring, will be lost, and fresh attacks upon us will be encouraged."

The original article was published in the EIR Online’s Electronic Intelligence Weekly, as part of an ongoing series on history, with a special emphasis on American history. We are reprinting and updating these articles now to assist our readers in understanding of the American System of Economy.