This Week in History

February 5-11, 1779:

George Rogers Clark Captures Vincennes

February 2012

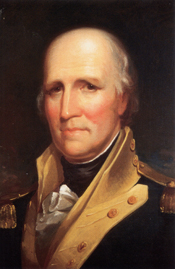

General George Rogers Clark..

|

"I know the case is desperate, but Sir, we must either quit the country or attack Mr. Hamilton. Great things have been effected by a few men well conducted. Perhaps we may be fortunate." So wrote George Rogers Clark from the Illinois Country to Gov. Patrick Henry of Virginia. Two days later, on Feb. 6, 1779, Clark led a small force of 170 men, half of them French, toward British Lt. Gov. Henry Hamilton's fort at Vincennes on the Wabash River.

Hamilton was known as the "Hair Buyer," due to his zealous enforcement of the British policy of paying bounties to the Indians for the delivery of American scalps or prisoners to Detroit. The main targets of these British-allied Indians were the Kentucky "stations," where small numbers of pioneers had placed themselves between the western British outposts and the vulnerable American frontiers further east. As long as the Kentuckians held out, the Ohio Valley Indians refused to attack across the mountains, for if they left their villages unprotected, the Kentuckians could destroy their corn crops. Knowing this, Hamilton had sent out 15 war parties from Detroit by July 1777, all of them headed for the 121 fighting men left in Kentucky.

George Rogers Clark, born in Virginia in 1752, had settled in Kentucky as a young man, and was determined to act "for the good of the country." First, he succeeded in having Kentucky given legal status as a new county of Virginia. Then, he proposed a secret plan to Gov. Henry, Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, and George Wythe. As the American Revolution raged in the East, Clark would recruit a small force and capture the British-controlled French towns in the Illinois Country, ceded to Britain after the French defeat in the French and Indian War. This would put the Americans on the Mississippi River, flanking the British headquarters at Detroit from the West.

On June 24, 1778, Clark and 170 men pushed off from their training base on Corn Island in the Ohio River, shot the rapids at the Falls of the Ohio (now Louisville), and double-manned the oars, day and night, until they reached the Tennessee River. From there, they marched overland into the Illinois Country, in order to avoid the British patrols which had been watching the confluence of the Ohio and the Mississippi Rivers. In short order, Clark's men captured the French villages of Kaskaskia, Cahokia, Prairie du Rocher, and Saint Phillips, and a delegation was sent eastward to secure Vincennes. Clark brought with him the news that the Americans were now allied with France, and many of the French inhabitants rallied to his cause. Clark also embarked on a series of diplomatic meetings with representatives of the Midwest Indian tribes, whom he asked to remain neutral in the conflict between America and Britain.

When Colonel Hamilton heard the news of the American successes, he quickly gathered a force in Detroit and marched for Vincennes. He was unhappy, however, that a part of his force consisted of French militia and volunteers. He complained that they were "ignorant Bigots and busy rebels," and declared that, "To enumerate the Vices of the Inhabitants would be to give a long catalogue, but to assert that they are not in possession of a single virtue, is no more than truth and justice require." He was more sure of his Indian allies, and many joined him, making a total force of around 600 men. Hamilton's army easily overwhelmed the token American force left in Vincennes, and the British Governor settled down to wait for spring, since the Wabash and Embarrass Rivers had flooded for miles around, making Vincennes virtually an island.

But Hamilton remained alert, and sent a party of Indians with a British officer to keep watch on the Ohio River. Other scouting parties were detached in an attempt to sever Clark's lines of communication with Kentucky and Virginia. Planning for his spring campaign, Hamilton suggested an early meeting with John Stuart, the British Indian agent in the South, at which they would coordinate their efforts to squeeze the Kentuckians in a vise. This done, Hamilton allowed much of his force to go home for the winter, leaving him with barely 100 men.

March to Vincennes by Frederick Coffay Yohn, painted in 1929.

|

When news came of the fall of Vincennes, Clark met with his officers, and they agreed that their position would be critical by spring, when Colonel Hamilton would have such a force "that nothing in this quarter could withstand his arms; that Kentucky must immediately fall, and well if the desolation would end there." They resolved "to attack the enemy in their quarters," counting on the value of surprise, for Hamilton would not expect a winter attack across 180 miles of flooded country. But the Americans and French did cross the Wabash on Feb. 21, after having marched through miles of water-covered land, some of it up to their shoulders.

Location of Vincennes, in Knox County(left) of the state of Indiana (right), on the border with Illinois.

|

Camping secretly out of sight of the town, Clark sent a message in to the French inhabitants, telling them to stay indoors because he would attack Hamilton that night. Then he marched his men in and out of the hillocks on the edge of town, flying every flag and banner they had brought, so that his force looked much bigger than it actually was. None of the French warned the British of his presence, and when Clark's men slipped into town after dark, some of the French gave them gunpowder which they had buried when the British recaptured the town. After brisk fighting around the fort, Hamilton consulted his officers as to whether they should accept Clark's demand for surrender. According to him, the English "to a man" were for continuing the fight, but the French militia and volunteers, whom he so abhorred, were reluctant to fight friends and relatives who had joined the Americans. On Feb. 25, Hamilton surrendered the fort to Clark.

Clark and his men still intended to capture the British post at Detroit, but the lack of men who could be spared from the fighting in the East, meant that the campaign had to be postponed again and again. Finally, the treaty signed at the end of the American Revolution ceded Detroit to the Americans, but the British refused to give it up. They explained that no Americans had arrived to accept the surrender of the post, but at the same time they deployed their Indian allies around all approaches to Detroit, so that any American expeditions were repulsed. The British held Detroit through the Confederation period and well into George Washington's Presidency. Finally, Gen. Anthony Wayne and his American Legion defeated Britain's Indian allies at Fallen Timbers, and without their defensive screen, the British were forced to withdraw in 1795.

George Rogers Clark lived not only to see Detroit pass into American hands, but, in 1806, he received two very welcome visitors. His younger brother, William Clark, and Meriwether Lewis came to his home in Indiana on the way back from their expedition to the Pacific Coast. It was an expedition which, many years previously, Thomas Jefferson had requested that he himself undertake.