This Week in History

May 5-11, 1803:

Meriwether Lewis Prepares to Lead the Corps of Discovery

by Pamela Lowry

May 2013

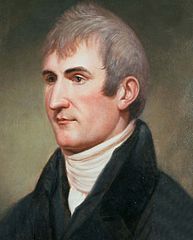

Meriwether Lewis, by Charles Wilson Peale.

|

On May 7, 1803, Meriwether Lewis left Lancaster, Pennsylvania and headed for Philadelphia. He was halfway through his mission to equip the Corps of Discovery for its journey to the Pacific, and to become skilled in the scientific techniques he would need to ensure the success of the expedition. His route led from President Jefferson's White House through Harpers Ferry, the new Federal Arsenal founded in 1796, and then north to Lancaster, which had served as the "Workshop of the American Revolution," and was a center of science and technology, second only to Philadelphia.

President Jefferson had written to many of his friends in the American Philosophical Society, founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1743, to promote American scientific development, asking them to assist Lewis. Lewis in turn, during the course of his preparations for the unknown conditions ahead, showed himself to be a very skilled planner. He developed improvements in technology which were useful not only to the expedition, but also to the new nation.

Meriwether Lewis had not been chosen to lead the expedition to the Pacific because he was President Jefferson's secretary, on the contrary, he was chosen by Jefferson to be his secretary because, as Jefferson wrote to Lewis' commanding officer, he needed someone who possessed a knowledge of both the Army and the "Western Country." Jefferson, on becoming President, pulled Lewis out of the Army and into the White House because he already intended to implement the long-planned expedition up the Missouri River to the Pacific.

Lewis had joined the Virginia Militia at the age of 20 in 1794, in response to President Washington's call for troops to quell the Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania. In May of the next year, he transferred into the regular U.S. Army, serving in Gen. Anthony Wayne's American Legion in the Northwest Territory. He was present at the Treaty of Greenville, which made peace with the Midwest Indian tribes, thus forcing the British Army to at last withdraw from their base at Detroit, as was stipulated 10 years earlier, at the end of America's War for Independence. The British had kept their Indian allies in front of Detroit as a screen, claiming that they could not give up the post because no American had come to claim it.

Anthony Wayne considered Meriwether Lewis to be one of his most promising young officers, and regularly sent him on difficult missions from the new American post at Detroit through the wilderness to Pittsburgh and back. While serving under Wayne, Lewis was transferred into the Chosen Rifle Company of sharpshooters, under the command of his future fast friend and expedition co-leader, William Clark. In 1797, Lewis commanded an infantry company which was stationed at Fort Pickering on the Chickasaw Bluffs, overlooking the Mississippi. There, in Cherokee country, Lewis continued to study Indian customs and languages, as he had done earlier in the land of the Wyandot and Shawnee.

In 1800, he was promoted to captain, and appointed regimental paymaster. Far from being a sedentary assignment, the position required regular tours of small frontier garrisons located in the future states of Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and West Virginia. On one such trip, Lewis gained valuable experience by taking a 21-foot keelboat and a dugout canoe down the Ohio River. By the time President Jefferson's Feb. 23, 1801 letter, asking Lewis to come to the White House, arrived at Detroit, Lewis was indeed familiar with both the Army and the "Western Country."

On March 15, 1803, after extensive discussions with Jefferson, Lewis left Washington for Harpers Ferry. He had already designed what he called an "iron canoe," which would be used when the Missouri River narrowed to the point that the larger wooden boat he designed for the early part of the trip could no longer be used. Lewis had to stay a month in Harpers Ferry supervising the canoe's construction and conducting experiments. He wrote triumphantly to Jefferson that the canoe's folding ribs of wrought iron weighed only 44 pounds, making it very easy to carry over portages; but that those same ribs, covered with animal hides, would float 1,770 pounds of cargo and crew. When finished, the ribs were packed in waterproof canvas and shipped to Pittsburgh. They were not unpacked until needed at the Great Falls of the Missouri River in June 1805.

Except for powdered soup, Lewis planned to take no extensive food supplies on the expedition, so the Corps would have to live off their hunting ability. The firearms they took with them were, therefore, crucial, and Lewis made sure that they were of top quality and of differing types, so that if one model could not stand up under rough conditions, another two or three might. Although the Army regularly used muskets, Lewis had the advantage of having used rifles in his sharpshooter company. He ordered a hybrid type from the Harpers Ferry Arsenal, which was like the famed Pennsylvania rifle, but with a shorter barrel. It became, with only two minor modifications, Model 1803, the first regulation rifle for the U.S. Army.

Lewis also helped develop a creative way to carry the large amount of gunpowder that his men would need. He had his 176 pounds of gunpowder put up in 52 water-tight lead canisters which could be melted down and molded into exactly the right number of rifle balls required by the amount of powder in each canister. Preparing even for the eventuality of running out of powder, Lewis purchased, with money from his own pocket, one of the new air rifles, which had just come on the market.

Once work on other aspects of the expedition's gear was well underway at Harpers Ferry, Lewis made his way to Lancaster, Pa., where he was to be trained in surveying and mapmaking. Lancaster had been an early center of research and development, into both the long rifle and the steamboat. William Henry, a close collaborator of Benjamin Franklin, had excelled in both, and had trained young Robert Fulton, who was now in France conducting his steamboat experiments. Less than a year after the Corps of Discovery returned to St. Louis, in September 1806, Fulton would make his first successful steamboat run up the Hudson. And by 1811, a Fulton-designed steamboat, built by Nicholas Roosevelt in Pittsburgh, would be sailing on the western waters explored by Lewis and Clark.

In Lancaster, Lewis bought a number of Pennsylvania long rifles, and worked with Andrew Ellicott, one of America's leading astronomers and mathematicians, who had also collaborated with William Henry. After serving in the American Revolution, Ellicott had helped to run the western part of the Mason-Dixon line. He also served on the commission to locate the northern and western boundaries of Pennsylvania, and, later, ran the southwestern border of New York State. He then succeeded Pierre L'Enfant as surveyor of the national capital at Washington, D.C.

Lewis began his course of study, and reported to Jefferson on April 20 that, "I have commenced, under his direction, my observations &c to perfect myself in the use and application of the instruments." It was decided that the "indispensably necessary" instruments needed for the expedition were two sextants, an artificial horizon or two, a good Arnold's watch or chronometer surveyor's compass with a ball and socket and two-pole chain, and a set of plotting instruments. Becoming proficient in surveying took longer than either Jefferson or Lewis had thought, but, by May 7, Lewis felt competent enough to embark on the next leg of his journey. He entered a stagecoach and travelled at the previously unheard-of speed of five to seven miles an hour down the Lancaster Turnpike, America's first gravel road, toward his meetings with scientists and merchants of Philadelphia.

The original article was published in the EIR Online’s Electronic Intelligence Weekly, as part of an ongoing series on history, with a special emphasis on American history. We are reprinting and updating these articles now to assist our readers in understanding of the American System of Economy.