This Week in History

March 24-30, 1584:

Walter Raleigh Receives a Charter — To Colonize North America

March 2013

Sir Walter Raleigh.

|

429 years ago, on March 25, 1584, Queen Elizabeth I granted a charter to Walter Raleigh, authorizing him to set up an English colony in lands not under the dominion of any Christian prince on friendly terms with England. Nothing was said about the exact location of the colony, but British expeditions had been exploring the area from Spanish and French Florida up to Newfoundland for a number of decades. Elizabeth's grandfather Henry VII had agreed to sponsor the westward voyages of Christopher Columbus, but when the explorer's brother returned from England with the happy news, Columbus had already begun his first voyage under the sponsorship of Spain. So England began its own series of explorations, and by the time of Elizabeth, many of the navigators of those voyages were concentrated in the West Country of England.

Walter Raleigh grew up in the west of England, and many of his relatives were part of the exploring group. Sir Francis Drake was his cousin, and Humphrey Gilbert was his half-brother. In 1578, Raleigh had helped Gilbert plan an expedition to colonize Newfoundland, under the same kind of charter which Raleigh himself would later receive. The expedition was large and well planned, but after it reached Newfoundland, dissension began. After a fight with the Spaniards, Gilbert himself ordered the ships back to England, to try again at a more favorable time.

Spanish explorers had also been mapping the coast of North America, and in 1565, they massacred the French Protestant colony in Florida and moved up to explore the coast as far as Chesapeake Bay. Their Jesuit mission on the Rappahannock River, however, was wiped out by the Indians. Reprisals by the Spaniards against the Indians followed swiftly, but the Spaniards did not found a new mission. Thus, there were, at the time of Raleigh's expeditions, no colonies of other European nations on the east coast of North America.

The intense rivalry between European powers over colonizing America was a mirror of the devastating religious wars which were raging in Europe, and were only brought to an end by the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia. To most observers of the time, the causes were national rivalries or strong religious differences. But above these proximate causes, and "pulling their strings," was a reaction by the former feudal powers against the ideas of the Golden Renaissance, which recognized that man, created in the image of God, must not be treated as a beast. It was the Renaissance ideas which finally succeeded in shaping the colonization and eventual sovereign development of the United States.

Once Raleigh had obtained his charter, he was not one to tarry, and he had a preliminary expedition on the way to America by April 27 of the same year. Although he yearned to accompany it, the Queen insisted that he remain at court. Raleigh's two ships were commanded by Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlow, and it was Barlow who wrote an account of the expedition. On July 4, they sighted the southern part of the east coast, and "sailed along the same a hundred and twenty English miles, before we could find any entrance, or river issuing into the sea." They finally reached the Barrier Islands of the future North Carolina, where they landed and planted the Arms of England.

Barlow and his associates were much impressed with the fertility of the islands, and viewed them almost as a Garden of Eden. "We viewed the land about us, being, whereat we first landed, very sandy and low towards the water side, but so full of grapes, as the very beating and surge of the sea overflowed them of which we found such plenty, as well there as in all places else, both on the sand and on the green soil, on the hills, as in the plains, as well on every little shrub, as also climbing towards the tops of high cedars, that I think in all the world the like abundance is not to be found, and myself having seen those parts of Europe that most abound, find such difference as were incredible to be written."

The Indians appeared after two days and were very hospitable. When the expedition returned to England, it left two Englishmen there as hostages for the safe return of two Indians, Manteo, and Wanchese, who were to see London, and, it was hoped, learn the English language so that the explorers could learn their Indian language. Barlow had reported that "We found the people most gentle, loving and faithful, void of all guile and treason, and such as live after the manner of the golden age." However, there is evidence, which Barlow failed to report, that perhaps these Indians were not quite as pacific as Barlow represented them to be. For example, one of the tribal chiefs was recovering from a war wound, and that the most appreciated gift to another chief was a round metal object that he could use as a breastplate to defend himself against the arrows of opposing tribes.

|

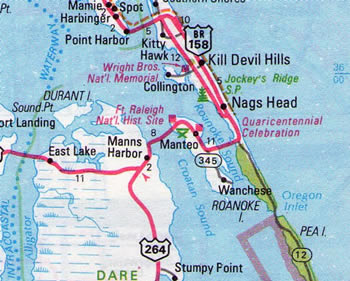

Above: Roanoke Island and environs (area inside box in the map on the left, of eastern North Carolina). Croatoan Island is called "Pea I." in this map, and is more commonly known as Hatteras Island, and the bend in the island (about 30 miles south of the limit of the area in the box, which covers about 32 miles from north to south) is known as Cape Hatteras.

|

When the two ships returned, Queen Elizabeth knighted Raleigh, and the colony was named "Virginia" in honor of the Virgin Queen. Raleigh recruited families and planned for a city to be built in the colony. In 1585, the colonists were landed on Roanoke Island, but instead of concentrating on establishing a firm base, they spent much of their time in exploration and managed to alienate the Indians. When Sir Francis Drake appeared, back from fighting the Spanish in South America and the Caribbean, the colonists begged to be taken home. Fifteen men were left on the site, but the relief ship sent by Raleigh for the colony could find no one.

In 1587, Raleigh mounted another effort, this time directing the colonists to settle in Chesapeake Bay, which avoided the alienated Indians and provided much easier maneuvering room for the ships. But their pilot led them again to Roanoke Island, where they had a difficult time. Governor John White, the grandfather of the first baby born in the colony, Virginia Dare, set sail for England to procure supplies and to obtain Raleigh's advice. He was unable to return because all ships were confiscated by the Queen for the defense of England against the Spanish Armada.

When White was finally able to reach Roanoke Island in 1590, he found the word "Croatoan" carved in one of the posts of the fort, without the cross which White had arranged as a signal for the colonists to use if they were in distress. Croatoan was the island where Manteo, one of the Indians who had visited London, lived, and so White assumed the colonists had run out of food and had to go live with their Indian friend. But both ships of White's convoy suffered damage, and they were not able to get to Croatoan. Then, in 1602, Raleigh sent another expedition to find the colonists, but its leaders failed, and wound up accomplishing nothing.

In 1603, Elizabeth died, and the new king, James I, was heavily influenced by Raleigh's enemies and eventually sent Raleigh to the Tower of London on a trumped-up charge of treason. Raleigh's rights in Virginia were transferred to the crown, and James granted them to the new Virginia Company. Captain John Smith carefully studied the reports of all of Raleigh's colonizing efforts, and this time, after many ups and downs, the colonization became permanent. Smith also scouted and charted New England, laying the basis for the actual republic founded by the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Raleigh was found guilty of treason in a mock trial, where he was denied counsel, was unable to confront his accusers, and in which only one highly pressured witness testified by deposition against him. Raleigh was later executed, but his conduct during the trial had an effect on the future United States. His trial became a cause célèbre, and many of America's Founding Fathers had read the published accounts of his well-reasoned defense and his criticism of the sham procedures. As the legal basis of a republic, the U.S. Constitution provides that "No person shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open court." The Sixth Amendment provides that the accused shall have the right "to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense."

The original article was published in the EIR Online’s Electronic Intelligence Weekly, as part of an ongoing series on history, with a special emphasis on American history. We are reprinting and updating these articles now to assist our readers in understanding of the American System of Economy.