November 6 - 12, 1794

A Daring Attempt

To Rescue Lafayette from Prison

November 2011

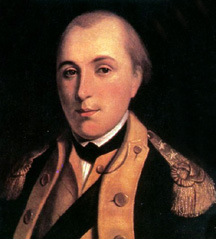

Marquis de Lafayette

|

On Nov. 8, 1794, a young German doctor and an American medical student joined forces in an unsuccessful attempt to free the Marquis de Lafayette from an Austrian prison. Lafayette and two fellow prisoners—all three, former members of France's Constituent Assembly—were famous throughout Europe and America as "The Prisoners of Olmutz," unjustly imprisoned by the monarchists of Europe, after they had fled from Robespierre's Reign of Terror in France.

A little more than two years earlier, Lafayette had been in command of the French Army on the northern frontier, poised to repel an invasion by Austria and Prussia. The early phases of the French Revolution, led by Lafayette and Jean Bailly, had established a constitutional monarchy, but the crowned heads of Europe were determined to return France to an absolute monarchy. This was important to accomplish before any such "dangerous" constitutional notions, so recently displayed by the independence of the United States, could spread to the rest of Europe. To this end, they played a double game. While royal armies threatened invasion and the royalist party in France desperately blocked any moderate solution, Great Britain trained, and then backed Marat and Danton, the leadership of the radical Jacobins who would destroy France from within.

The moderates were still in power in France, but the Jacobin Clubs were urging soldiers to murder their officers, and were blocking supplies from being sent to Lafayette's army. Erich Bollmann, the same young doctor who would try to rescue Lafayette, was training at hospitals in Paris at the time, and wrote, "The Jacobins hate LaFayette because he is the only man that can withstand them. They preach his murder in the streets."

On June 16, 1792, Lafayette wrote to the French Assembly, denouncing the Jacobin Clubs and encouraging the Assembly to use its powers under the constitution to prevent the destruction of the nation. He described the Jacobins as "organized like a separate empire, with its headquarters and its branches, blindly directed by ambitious chiefs, which sect forms a separate and distinct corporation in the midst of the French people, and usurps the powers of the people, by subjugating their representatives and their servants." The Jacobins subjugated the representatives in the Assembly through fear—Jacobin control of the Paris mobs was well known, and they could be targetted against anyone who was denounced as being a traitor to the republic.

Trying to find some way to maintain the constitutional republic, Lafayette rode to Paris and addressed the Assembly, but, terrified by the mobs, it refused to act. When a bill of impeachment against Lafayette was entered on Aug. 8, the moderates were still strong enough to defeat it by a vote of 446-224, but the queen and the nobles opposed any plan he proposed to save the constitutional monarchy. Queen Marie Antoinette said that she and the king did not want to owe their life to Lafayette twice, and the nobles averred that although they knew Lafayette would try to save the king, he would not save the titles of the nobility.

Jacobin mobs of the French Revolution.

|

From outside France, the monarchists added to the rage of the Jacobin mobs. The Duke of Brunswick issued an insulting proclamation which stated that if Paris did not submit to Louis XVI, then the monarchist allies would "take exemplary vengeance, memorable forever, delivering up the city of Paris to military execution and total overthrow." On Aug. 10, when Lafayette had returned to the front, the Paris Commune took over the French Government, slaughtered the Swiss Guards who defended the king, and made the royal family their prisoners. Lafayette considered marching to Paris with the loyal part of the army, but other generals refused to go with him, as Jacobin influence in the army was becoming stronger.

On Aug. 17, the French Executive Council decreed that Lafayette should transfer his command to another general and come to Paris to answer charges. On Aug. 19, he was charged with rebellion and treason, a price was put on his head, and pledges were given to bring him to Paris dead or alive. In this impossible situation, Lafayette took some of his officers with him and rode north to the border, intending to sail to America from Holland. His group was intercepted by the Austrians, and Lafayette was imprisoned under Prussian control, first at Wesel on the Rhine, and then at Magdebourg on the Elbe.

Lafayette's conditions of imprisonment were terrible—he was held in underground cells dripping with moisture and with no direct light. He was not allowed to communicate with the outside world by letter or message. He was watched day and night, and his jailers were not allowed to talk to him. He was moved from prison to prison often enough so that his friends would not know where to find him. Years later, he found out that at a conference held to decide upon his fate, it was stated that, "Monsieur Lafayette is not only the promoter of the French Revolution but of world-wide liberty.... The existence of Monsieur de Lafayette is inconsistent with the safety of the governments of Europe."

After George Washington wrote a letter to the Austrian emperor, Lafayette was allowed to write to a few friends, but his prison conditions remained grim. Finally, after a suspicious illness, Lafayette concluded that he might not leave prison alive, and he wrote secretly to friends in England that an attempt should be made to rescue him. The group that received this letter included old family friends such as the French Princess d'Henin, émigrés, and Americans such as Thomas Pinckney, Washington's Ambassador to the Court of St. James. Casting about for someone to carry out the mission, they lighted upon the young German physician Erich Bollmann, who had already succeeded in smuggling the ex-Minister of War out of Paris to England. But Lafayette had been moved to another prison, and none of his friends knew where he was.

Bollmann searched for news of Lafayette through Saxony and Silesia, and finally discovered that Austrian soldiers had been seen escorting Lafayette in the direction of the Austrian town of Olmutz. He went there and began to make visits to the hospital, where he became friendly with the chief surgeon. One day he asked casually how Lafayette was doing, and the surgeon told him that Lafayette was fine. Through the surgeon, Bollmann managed to send Lafayette some books, which had secret messages written in lemon juice on the margins. Bollmann learned from Lafayette's innocent-looking return letters that he would ask to be allowed to ride out in the air for his health, and that the escape attempt should be made when he had ridden out far from the prison.

Because he needed help and equipment, Bollmann went to Vienna, where he met young Francis Huger, an American medical student who, as a young boy, had met Lafayette during the American Revolution. When Lafayette arrived in America from France, his ship had dropped anchor off South Carolina, and he was welcomed into the Huger home. Therefore, Huger was eager to help save Lafayette, and he agreed to pose as a young English lord with Bollmann as his supposed tutor. This gave them the cover to have a carriage, a servant on horseback, and to travel freely.

On the appointed day, Lafayette rode out in a carriage with two guards, and then proposed to get out and walk. He mopped his brow with a handkerchief as a signal to Bollmann and Huger, who quickly rode in and grappled with the guards. Lafayette mounted one of their horses and was told to ride to Hoff, where the servant waited with fresh horses, but he took the wrong fork in the road. One of the other horses bolted, so Bollmann made for the border and Huger tried to escape on foot. The Austrians pursued all three and eventually captured them.

Lafayette suffered greatly from the fear that his brave rescuers would be executed on his account, for the prison superintendent swore that they would be hanged before his window. But Bollmann and Huger were imprisoned only for seven months and were released in July 1795. They made it over the border just in time, because the Austrian emperor reconsidered and ordered their case reopened because he considered their sentence too light.

Adrienne, Marquise de Lafayette

|

Both went to the United States, where Bollmann later became involved with the western separatist schemes of Aaron Burr. Francis Huger became a practicing doctor, and had the pleasure of greeting Lafayette when he arrived for his 1824 visit to the United States.

Lafayette endured another three years of prison, but was protected against assassination by the arrival of his wife, Adrienne. She had also suffered years of imprisonment under the Terror in France, but upon her release she immediately travelled to Austria to share her husband's prison cell and protect his life. Their devotion is celebrated in Beethoven's great opera Fidelio.

The original article was published in the EIR Online’s Electronic Intelligence Weekly, as part of an ongoing series on history, with a special emphasis on American history. We are reprinting and updating these articles now to assist our readers in understanding of the American System of Economy.