This Week in History:

September 14 - 20, 2014

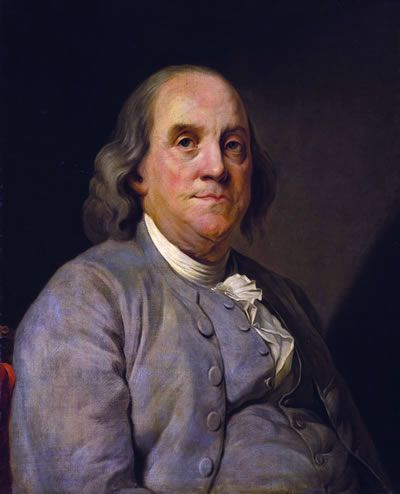

Benjamin Franklin Makes His Final Speech

to the Constitutional Convention

September 17, 1787

As Americans in 2014 see the sacred U.S Constitution ripped to shreds by a treasonous puppet President, it is important to reiterate the process by which this profound statement of principle was organized and fought for. It was the work of Benjamin Franklin, already known throughout the world through as the "American Prometheus" who not only fathered the American Revolution beginning in 1763, but whose scientific genius and strategic thinking, like that of Lyndon LaRouche today, was instrumental in resolving the conflicts that constantly arose, always from the highest standpoint. We reproduce this article now, as new international institutions and development banks are coming into existence, as a contribution to the process of creating a world without war, based on the Common Aims of Mankind.

"We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America."

- read the full document here http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution_transcript.html

Benjamin Franklin. |

September 17, 1787 was the last day of the convention which had drafted the United States Constitution, and it was now time for the delegates to sign the document. The leaders of the convention were worried that there was a small minority in the convention made up of delegates who had argued for various measures and been defeated, and thus might refuse to sign the final document, endangering future ratification by the states. They went to Franklin and asked him to give a speech which would appeal for unity. Franklin's speech on that last day was crucial, but it was only the capstone on what he had done, both before and during the convention, to ensure it would produce the basis for an enduring republic.

Almost exactly two years earlier, Franklin had returned to Philadelphia from his mission in Europe, where he had cemented an alliance with France, rallied Europeans to support the American Revolution, and signed the treaty which recognized the independence of the new nation. Now about to enter his 80s, and suffering from an extremely painful kidney stone, he slowly made his way overland to his French port of embarkation, travelling in a sedan chair sent by Queen Marie Antoinette herself. Once in Philadelphia, he was elected to the Presidency of Pennsylvania, and continued his scientific work as president of the American Philosophical Society.

But the weak Articles of Confederation government set up during the Revolution was failing, and Franklin had larger objectives in view. Uncharacteristically, for one who had lived fairly simply, Franklin embarked on a major renovation of his house. He designed a 16x30-foot addition which gave him a dining room seating 24 people, and an upstairs library which could contain 40,000 volumes. Had the Court at Versailles given him delusions of grandeur?

Anyone who had read his Autobiography would have known what to expect next. When the call went out for a convention to reform the Articles of Confederation, Ben Franklin took a page from his own book, and organized a group called the Society for Political Inquiries, which met weekly in his library. It was modelled on the "reforming societies" such as "Young Men Associated" which had been organized by his mentor, Cotton Mather, to train up a generation of Boston citizens who knew how to do good. It was also modelled on Franklin's own Junto, which he had founded in Philadelphia in 1727, and which, for almost 40 years was, as described by Franklin, "the best school of philosophy and politics that then existed in the province."

While the states were electing delegates to the convention, the Society for Political Inquiries was discussing theories of government, writing essays on political topics, and proposing prize questions which other authors could write upon. Although the active members were mainly from the Philadelphia area, the group enrolled honorary members from throughout the states, including George Washington. The Society continued to function throughout the convention, the fight for state ratification, and the inauguration of President George Washington, only disbanding by the vote of its members when the new nation had been launched on a solid footing.

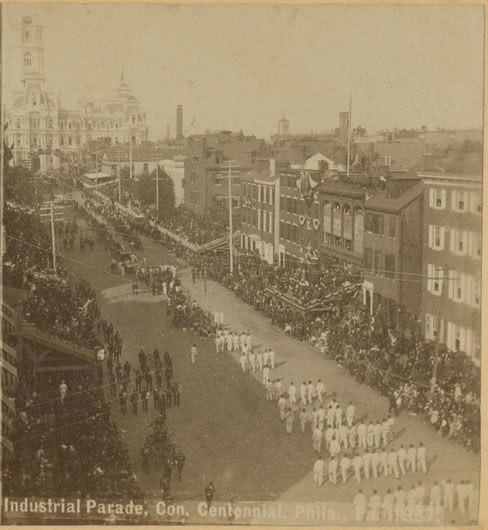

|

Publisher: United States. Source: Libary Company of Philadelphia

View showing the civic and industrial parade on South Broad Street marching toward City Hall. The procession represented industrial progress from 1787 to 1887. Shows spectators crowding the sidewalks and sitting on bleachers lining the street. Procession includes: a group of marching men in black hats, white pants, and white shirts; floats; a marching band; and firemen. City Hall is visible in the background.. |

As the delegates reached Philadelphia in May, they went to pay their respects to Franklin, who, as President of Pennsylvania, was the unofficial host of the convention. His dining room seating for 24 was strained to the maximum, as he wrote to a London brewer who had sent him a cask of porter: "We have here at present what the French call une assemblée des notables, a convention composed of some of the principal people from the several states of our confederation. They did me the honour of dining with me last Wednesday, when the cask was broached, and its contents met with the most cordial reception and universal approbation."

There were only two candidates for president of the convention—Washington and Franklin. Franklin deferred to Washington, and when he could not nominate him in person on the first day of the meeting, he had the Pennsylvania delegation do it in his stead. Never known as an orator, Franklin did not speak often at the convention, and focussed his energies—five hours a day for four months—on working for compromise and the best plan that could be obtained. He himself favored features, such as a unicameral legislature and paying only expenses for the executive, that were voted down by the delegates. He took the defeats gracefully, but other delegates were not so calm.

The great stumbling block for the convention was the question of what kind of legislative representation would satisfy both the large and the smaller states. The level of debate became so acrimonious that a delegate from a smaller state warned that they might find a foreign ally and secede. A delegate from a large state threatened that if that event occurred, the nation would suffer under fire and sword, and officials of the smaller states would face the gallows for treason. Franklin stepped into the fray and calmly told the delegates that, "The diversity of opinion turns on two points. If a proportional representation takes place, the small states contend that their liberties will be in danger. If an equality of votes is to be put in its place, the large states say their money will be in danger."

Franklin then called for compromise. "When a broad table is to be made, and the edges of the planks do not fit, the artist takes a little from both, and makes a good joint. In like manner here, both sides must part with some of their demands in order that they may join in some accommodating purpose." He then submitted a motion, where the delegates could fill in the number which he left blank: "That the legislatures of the several states shall choose and send an equal number of delegates, namely ____, who are to compose the second branch of the general legislature." This motion was passed, and so the House of Representatives would be selected according to population, but the Senate would give states equal representation. This broke the logjam in the convention and allowed the Constitution to be further filled out.

On the last day, the only remaining obstacle was whether the bitter holdouts would sink the Constitution's chances to be ratified by the states. Worn out by his pain and his incessant labors for compromise, Franklin had to ask James Wilson to deliver the following speech:

"Mr. President, I confess, that I do not entirely approve of this Constitution at present; but, Sir, I am not sure I shall never approve it; for, having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged, by better information or fuller consideration to change my opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise....

"In these sentiments, Sir, I agree to this Constitution, with all its faults—if they are such; because I think a general Government necessary for us, and there is no form of government but what may be a blessing to the people, if well administered; and I believe, farther, that this is likely to be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic government, being incapable of any other. I doubt, too, whether any other Convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better constitution; for, when you assemble a number of men, to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an assembly can a perfect production be expected?

"It therefore astonishes me, Sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does; and I think it will astonish our enemies, who are waiting with confidence to hear, that our councils are confounded like those of the builders of Babel, and that our States are on the point of separation, only to meet hereafter for the purpose of cutting one another's throats. Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution, because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best. The opinions I have had of its errors I sacrifice to the public good. I have never whispered a syllable of them abroad. Within these walls they were born, and here they shall die....

"Much of the strength and efficiency of any government, in procuring and securing happiness to the people, depends on opinion, on the general opinion of the goodness of that government, as well as of the wisdom and integrity of its governors. I hope, therefore, for our own sakes, as a part of the people, and for the sake of our posterity, that we shall act heartily and unanimously in recommending this Constitution, wherever our Influence may extend, and turn our future thoughts and endeavours to the means of having it well administered.

"On the whole, Sir, I cannot help expressing a wish, that every member of the Convention who may still have objections to it, would with me on this occasion doubt a little of his own infallibility, and, to make manifest our unanimity, put his name to this Instrument."