Image of the American Patriot

VI. Andrew Jackson as A Treason Project

by Anton Chaitkin

December 2007

Table of Contents for this series

Preface: The Jackson Lie And the Current Crisis

Every year, Democratic Party leaders stage an ugly ritual known as "Jefferson-Jackson Day."

They give this name to fund-raising events, to boast that their party continues a political tradition inherited from the early U.S. Presidents Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson.

This fraud is designed to bury the legacy of the most famous and revered Democratic President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and to declare the party's allegiance to a political philosophy directly opposed to Roosevelt's.

FDR used national power to protect the rights of workers and the poor, and to promote universal economic progress, thus reviving those activist-government initiatives of America's founders and of Abraham Lincoln, which the world so admired. Roosevelt rescued the people from the 1930s Great Depression, and led the forces defeating Hitlerism in World War II.

Roosevelt's London and Wall Street enemies asserted that men have no right to progress, that government must not protect wages or otherwise interfere with colonial subjugation, looting, and backwardness.

This brutal anti-national philosophy, practiced on the world by the British Empire, came into the White House with Andrew Jackson's Presidency (1829-37). The first President under the new "Democratic Party," Jackson was an enemy of the earlier, more nationalistic President Thomas Jefferson, whose administration (1801-09) had subpoenaed Jackson to testify as an unindicted co-conspirator in the treason trial of Aaron Burr.

President Jackson broke down the nation's power over credit, tore down the tariffs protecting U.S. industry and wages, and blocked national expansion of canals and railroads.

As a result, the industrial economy crashed, and Southern states gave up plans to acquire industry and abolish slavery. A cheap-labor ("free-trade") alliance of plantation slaveholders and their British cotton customers fostered anti-national radicalism in the South. Jackson destroyed the previous American consensus behind nationalist economics, in which Southern leaders such as Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, and John C. Calhoun had all participated. This political catastrophe is the origin of the Slave Power, and of the Civil War.

But you have no doubt heard that Andrew Jackson was "the people's" champion, who enhanced the power of "the little guy"—a dogma always repeated at the above-cited fund-raising dinners.

You may also have heard that the current national leadership of the Democrats, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and her ilk (those who put on those historically fraudulent rituals) have blocked Franklin Roosevelt-style action by Democrats to rescue the country from economic collapse and imperial disaster.

The "Jackson, not FDR" policy was imposed on the Democratic Party in association with a history hoax published in 1946, just after Roosevelt's death: The Age of Jackson, by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. In it Andrew Jackson is sold as "the people's own President," his reign as "the rule of the people."

Who Jackson was in fact, and whose instrument, will be documented in the present report.

Library of Congress |

Andrew Jackson brought the philosophy of the British Empire into the White House for the first time, destroying the Bank of the United States and the tariffs that protected American industry. |

Schlesinger's book came out as the British establishment, from Winston Churchill to Bertrand Russell, were rushing to reprogram the war-triumphant U.S.A. away from Roosevelt's anti-colonial program. By 1950, Schlesinger, Russell, Allen Dulles, and Sidney Hook would be among the leaders of the Congress for Cultural Freedom,[1] designed to nail the coffin shut on the American Revolution, and the mother enterprise of what would become neoconservatism.

The Age of Jackson explains that "Southern planters" provided "the mass with leadership in their struggle for political power,"[2] that slaveowners' political operatives, by backing Jackson, "kept alive the democratic soul," against "the aggressions of a central government controlled by a moneyed aristocracy."[3]

Hoping that his readers know nothing of pre-Civil War American history, Schlesinger never presents two stark features of that period's politics:

1. That the Northeastern aristocrats who came to dominate the Federalist Party ("against Jefferson") were notoriously British-allied anti-nationalists, not Hamiltonians; and

2. That Henry Clay-led nationalism was premised on a world contest against the British Empire and European oligarchism. In the time of Jackson, such patriots as James Fenimore Cooper might be found as Democrats, in opposition to the influence of "anti-Jackson" (i.e., Whig) Northeastern aristocrats, just as Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams had adhered to the party of Jefferson despite their Hamiltonian principles, in opposition to the core oligarchical alliance of Britain, the Boston tories, and the worst Southern planters. The pro-high-tariff Cooper and the Indian-slaughtering thug Andrew Jackson had nothing in common.

—————————————————————————

Setting the Stage

Library of Congress Henry Clay rallied support for a re-born nationalist program—the policies that he called “the American System.” |

The revival of nationalism had begun in 1810. Henry Clay had led in electing to Congress feisty advocates of war against the British Empire—Clay's "War Hawks." This anti-imperial movement, committed as well to Alexander Hamilton's nationalist economic program, elicited fear and loathing from the Anglophile treason faction, and from the British, speaking in their own name.

As Congress debated whether to defend the United States from British military attacks, Boston Congressman Josiah Quincy (one of the Massachusetts "Essex Junto" that was scheming for New England to secede) called Clay's patriots "toad eaters"—commoners who had usurped the places of their betters in government. Clay said he was not disturbed "by the howlings of the whole British pack let loose from the Essex kennel."

The newly installed British ambassador to Washington, John Augustus Foster, wrote hopefully to the Foreign Office that since the James Madison Administration would not allow itself to "be pushed into a War with us...there never was a more favourable moment for Great Britain to impose almost what terms she pleases."[4]

But under Clay's leadership, President Madison was made to understand that he would not be supported for a second Presidential term, if he did not come out for war with Britain.

Madison began issuing pro-war messages, and the Democratic caucus renominated him. For insurance, republican forces in New York secure the nomination of the nationalist DeWitt Clinton for U.S. President. There was no official Federalist candidate. At Madison's request, Congress declared war on Britain in June 1812.

British Ambassador Foster lamented the loss of "the old Democratic Party"—i.e., Albert Gallatin's free-trade gang, which had stood for economy, states' rights, and peace with England—and was, in a colonial fashion, England's best market and source of raw materials.[5] Previously, Gallatin's budget had had the effect of "damping the military ardour."[6]

Alarmed by an American political movement combining politicized city workers and internationally alert frontier farmers, the British ambassador denounced the large pro-war meetings in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and other seaports, which the Briton claimed were mobs "principally composed of Irishmen of the lowest order, Negros, and Boys."[7]

In retirement, former President Jefferson agreed with "this second weaning from British principles, British attachments, British manners and manufactures." He looked forward to the outcome of a war—"a spirit of nationalism and of consequent prosperity, which could never have resulted from a continued subordination to the interests and influence of England."[8]

The War of 1812 was entirely a defensive war, wherein the lightly armed and ill-prepared republic survived treachery by New England Federalist leaders and held its own militarily against the world's greatest power.

Following the conclusion of a peace treaty, it was clear that an entirely new political order had begun. Kentucky's Henry Clay and his Philadelphia ally, publisher Mathew Carey, had rallied countrywide support for a re-born nationalism, which would in ten years push through an astonishing program of technology development and westward-vectored transport. The resulting industrial revolution, delayed over the previous free-trade decades, would now give America muscle enough to survive even a Civil War.

The policies comprising what Clay dubbed "the American System" would become later identified with Clay's and Carey's Whig Party, and the nationalist program through which Abraham Lincoln completed the remaking of the United States as the world's leading industrial power.

The British Reaction

Lord Robert Gasocyne-Cecil, during the U.S. Civil War, hailed the Confederacy and demanded the breakup of the Union, saying the United States and Britain were “rivals politically, rivals commercially.” |

America's successful industrial breakout deeply frightened the British Empire and its foreign collaborators, and moved them to hostile countermeasures.

By the 1860s—35 years after John C. Calhoun's and John Q. Adams' U.S. Army Corps of Engineers designed the first railroad in South Carolina—the British-armed insurrection of the Southern slaveowners threatened to terminate the world's first modern republic.

Lord Robert Cecil (later known as the Marquess of Salisbury) lectured the House of Lords in 1862 on why the American Union should be broken up: "we are rivals, rivals politically, rivals commercially. We aspire to the same position. We both aspire to the government of the seas. We are both manufacturing people, and in every port, as well as at every court, we are rivals to each other.... With respect to the Southern States, the case is entirely reversed. The population are an agricultural people. They furnish the raw material of our industry, and they consume the products which we manufacture from it. With them, therefore, every interest must lead us to cultivate friendly relations, and we have seen that when the [American Civil] war began they at once recurred to England as their natural ally."[9]

John A. Roebuck, in the House of Commons a year later, put a bitter point to the matter: "America while she was united ran a race of prosperity unparalleled in the world. Eighty years made the Republic such a power, that if she had continued as she was a few years longer, she would have been the great bully of the world."[10]The American Civil War was the military showdown of a struggle which had continued since the time of the earliest European settlements in America, into the era of the Republic.

The leaders of the American Revolution and their 19th-Century nationalist successors, sought to build a continent-spanning power, freed of any colonial relationship to Europe. They would promote rapid industrialization. They fought for public education, and education for the aboriginal American Indians. To expand westward, they would connect the Mississippi River basin to the East Coast with rails and canals. They would contain the spread of black slavery; and to prepare for its ending, sought to link the South to the North and West with a railroad grid, and bring new industry into the South. They would befriend and industrialize Ibero-America and all emerging countries, aiding them to withstand imperialism.

The enemy—the colonial oligarchy, straddling the Atlantic—acted to prevent America's westward development, and to obstruct the connection of East and West; to stop industrialization, undermine city-building, and perpetuate the colonial plantation economy; to isolate and whip up the geographical sections against each other, disrupting the Union; to prohibit the integration of the Indians into American society; and to attack Mexico, Cuba, and Central America, to spread slavery and bring about anti-Americanism there.

In the political arena, this persistent treachery appeared before the public through what came to be called the Democratic Party, beginning with the Presidency of Andrew Jackson. Leaving aside the mass of the voters, who were as fickle those as in Shakespeare's tragi-comic scenes of crowd-manipulation in Julius Caesar, the pre-Civil War Democrats may be divided into three categories of political operatives:

1. A continuing clique of strategists and top managers, including Aaron Burr, Albert Gallatin, Martin Van Buren, August Belmont, John Slidell, and Caleb Cushing, a collection of criminals and foreign agents representing a British tory political machine that was never displaced from Boston, New York, and the South, after their side lost the American Revolution.

2. The Presidents: Jackson (1829-37), Van Buren himself (1837-41), John Tyler (1841-45—elected Vice President as a Whig, he betrayed the mandate after he assumed office upon the death of President William Henry Harrison), James Polk (1845-49), Franklin Pierce (1853-57) and James Buchanan (1857-61).

3. Numerous patriotic leaders, committed to the General Welfare, who helped mitigate the damage done to the nation by the radical anti-nationalists. Among such outstanding Democrats were Sam Houston (aide to Jackson; general, governor and president of Texas, and U.S. Senator); William J. Duane (Secretary of the Treasury, 1833); Joel Poinsett (Secretary of War, 1837-41); James K. Paulding (Secretary of the Navy, 1838-41).[11]Burr's and Van Buren's Jackson Project

The early Democratic Party was shaped principally by two rather overtly satanic personalities, New York political boss Martin Van Buren, and later, Rothschild financier and speculator August Belmont. The party came into being in the late 1820s around Burr's and Van Buren's project of making a celebrity President out of the thuggish Tennessee feudalist, Andrew Jackson.

Jackson began his career as a debt-collecting lawyer on the Tennessee frontier, after the American Revolution. His physical courage, strength, and endurance, his absolute ignorance of history or moral ideas, his intense rages, and his habit of shooting opponents made Jackson a valuable asset to the wealthiest land barons, slave traders, and speculators who were his clients and initial sponsors.

Frontier Tennessee was being pulled in two directions. In the tradition of pioneer patriot leader Daniel Boone, revolutionary militia chief John Sevier served as the popular first governor, after Tennessee was admitted to the Union as a state. Sevier and his associates worked for the orderly settlement and progress of the western United States. Opposed to Sevier and his supporters, were oligarchs and adventurers—including Jackson—concentrated in Nashville and western Tennessee, forming a political faction led by William Blount. Blount was accounted a pro-British "Federalist."

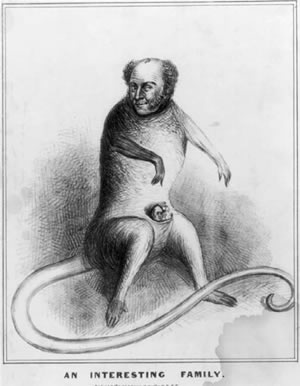

Traitor Aaron Burr. The British ambassador wrote to the Foreign Office that Burr had offered “to lend his assistance to his majesty’s government in any matter in which they may think fit to employ him, particularly in endeavoring to effect a separation of the western part of the United States from that which lies between the Atlantic and the mountains, in its whole extent.” Andrew Jackson was his ally in the project. |

At the outset of the independent republic, Spain, not the United States, controlled the lower Mississippi River, New Orleans, and the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. American settlers to the west of the Appalachian Mountains had as yet no practical means of transporting goods to the East Coast or Europe, except on the Mississippi and its tributaries, and thus had to traverse foreign territory. This American vulnerability in relation to the unstable Spanish Empire was a source of anxiety to the Union's defenders, and a lever of intrigue for the Spanish and, more importantly, for the British, who still had regular Army outposts (before the Jay Treaty, 1795), and Indian allies and irregular forces operating all around the American frontier. Adding to the problem was the fact that North Carolina, which had included the region of Tennessee, had at first rejected the U.S. Constitution.

The U.S. government commenced operations under the Constitution early in 1789. On Feb. 13, a few days before the First Congress went into session, the 21-year-old Andrew Jackson addressed a letter to his fellow intriguer, the district militia commander Daniel Smith.[12] In the letter Jackson introduced Smith to a French-born Spanish army officer and intelligence agent named Andrew Fagot, who was working to bring the western American settlements under Spanish control. Jackson transmitted Fagot's request to serve as an intermediary for disgruntled Americans to break their allegiance to the U.S.A. and make a treaty with the Spanish Governor of the Louisiana Territory, Estaban Miró. The charitable construction put on this and the subsequent transactions of what became known as the "Spanish Conspiracy," is that Jackson and his older colleagues did not view the United States as necessarily a permanent entity. Militia commander Smith sent Fagot back to Governor Miró, with a message accepting Fagot as the faction's representative.[13] Miró then wrote to the Spanish government: "The inhabitants of the Cumberland [i.e., Tennessee] ... would in September send delegates to North Carolina ... to solicit from the legislature ... an act of separation," which would place "the Territory under the dominion of His Majesty."[14] In October 1790, Jackson received from Governor Miró, without payment, a valuable tract of Mississippi riverfront land 30 miles north of Natchez, where Jackson commenced erecting a slave plantation.The George Washington Administration concluded a treaty with Spain in 1795, for the right of cargo deposit in New Orleans, which, with the admission of Tennessee to the Union in 1796, might have calmed the treasonous intrigues with the Spanish. But the British—at the time the world's only superpower—now came directly into play.

Faction leader William Blount went to the U.S. Senate. Andrew Jackson, whom Blount had boosted into politics, went to the House of Representatives. Eleven months after taking his seat, Blount was expelled from the Senate (July 8, 1797), for leading a plot to recruit American settlers and Indian tribes to aid the British military to seize the Gulf coast from Spain. The Blount forces designated Jackson as Blount's replacement, and Jackson was appointed to the U.S. Senate seat by the state legislature.

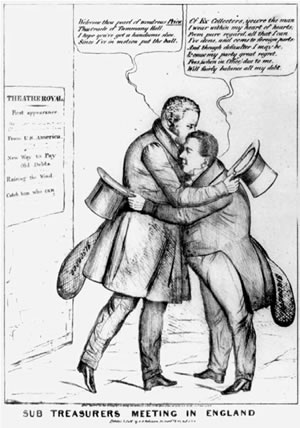

|

Library of Congress |

|

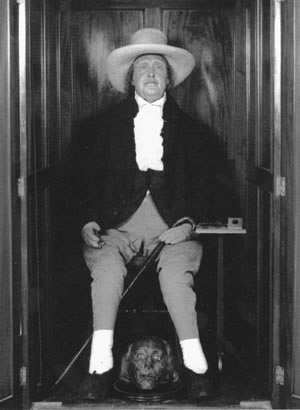

The “auto-icon” of Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), top strategist of the British secret intelligence service. This peculiar display was created according to Bentham’s own instructions, contained in his will. Bentham’s preserved skeleton is dressed in his own clothes, and topped with a wax head. Bentham’s actual head lies between his legs. Bentham was an avid sponsor of Burr and Jackson, and was hailed by Arthur Schlesinger as “the great English reformer.” |

|

This cartoon attacks Andrew Jackson’s plan to distribute Treasury funds, formerly kept in the Bank of the United States, to banks in various states. Jackson is the jackass in the center, “dancing among the chickens” (the state banks). Martin Van Buren is the fox (right). |

In this period Blount and Jackson both worked closely with Aaron Burr, who was a Senator until March 1797. Burr, who would launch the "Jackson for President" project, was connected by marriage to the highest-level British army and espionage leaders, and his New York political apparatus included British army colonel and intelligence officer Charles Williamson.

While he was U.S. Vice President, Burr fatally shot Alexander Hamilton (July 11, 1804), in a duel over Hamilton's exposé of Burr's treason. The coroner's jury returned a verdict of murder, and Burr fled to South Carolina, then to Philadelphia, where he conferred with Colonel Williamson, who had just escorted a new British ambassador, Anthony Merry, back from London to Washington. Merry then wrote back to the Foreign Office, "I have just received an offer from Mr. Burr ... to lend his assistance to his majesty's government in any matter in which they may think fit to employ him, particularly in endeavoring to effect a separation of the western part of the United States from that which lies between the Atlantic and the mountains, in its whole extent."[15] Colonel Williamson would immediately take Burr's proposals to Britain's Foreign Secretary Lord Harrowby.To effect this scheme, Burr's confederate Edward Livingston, formerly New York's mayor, had moved to Louisiana, when the United States gained control of it in 1803. Livingston and British intelligence agent James Workman formed the Mexican Association of New Orleans, whose avowed purpose was to seize Louisiana, and, together with a British naval force, conquer Spanish-controlled Mexico.

In May 1805, Burr arrived in Nashville, and spent nearly a week with Jackson at his home, the Hermitage. Jackson, then a major general of the Tennessee militia, began recruiting mercenaries for Burr's private army, and arranged for boats to float them down the Ohio and the Mississippi rivers. Shortly after Burr departed, Jackson killed a man in a duel. Burr went to New Orleans to arrange the insurrection, and returned in August to spend another week with Jackson.

Burr came back to the Hermitage again in September 1806, and Jackson arranged for him to be honored at a public ball as a "true and trusty friend of Tennessee."[16] In November 1806, Burr sent Jackson an order and $3,500 in cash for five boats and military provisions. Jackson had work started on the boats and got 75 men recruited for the Burr expedition.When a stranger stopped at the Hermitage, blabbing about the Burr plot to divide the Union, which the stranger was on his way to join, Jackson was alarmed at how widely and indiscriminately known the scheme had become. He sent out messages designed to put himself and Burr in the clear; he warned of a plan to divide the Union, and named U.S. Gen. James Wilkinson as the mastermind.

Meanwhile, Jackson expedited the building of the boats for Burr. The first legal action was taken against Burr's treason shortly afterward.

Wilkinson, whom Burr had sought to aid the plot, wrote to President Jefferson and exposed Burr. In November, Jefferson issued a proclamation warning of a conspiracy, ordering the plotters arrested, and asking patriotic citizens to aid their government. When the boats Burr had ready in Ohio were seized by state authorities, Burr returned to the Hermitage and Jackson gave him two of the boats under their contract, and sent his nephew along with the Burr expedition.

Secretary of War Henry Dearborn sent Jackson a letter (received Jan. 1, 1807), declaring that "it is industrially reported" among the Burr plotters "that they are to be joined by two regiments under the Command of General Jackson...." Dearborn asked Jackson to prove the reports wrong by helping to defeat the conspiracy.

Aaron Burr was arrested for treason while attempting to flee in disguise into Spanish territory. At Burr's trial in Richmond, Va., Jackson was subpoenaed as a star witness. During the trial, Jackson went into the streets to harangue the crowd against President Jefferson, as a coward who backs down in the face of British aggression, but persecutes and tortures Aaron Burr. This rhetoric against the anti-British Jefferson made Jackson very popular with tory political forces in the South.

Jackson told Burr's friend and Richmond defender, Congressman John Randolph of Roanoke, that Burr was innocent, that Wilkinson must be blamed for the conspiracy and for betraying Burr. In this period, Jackson and Randolph were members of a national faction known as the Quids, enemies of Jefferson who accused him of selling out the anti-nationalist cause. Randolph managed to become foreman of the grand jury for the Burr case, and the only evidence against Burr they allowed was an ambiguous letter to General Wilkinson. Such evidence as the British ambassador's letter on Burr's proposal was not known of until much later. The jury found Burr not guilty.

At the trial, Jackson made the acquaintance of Samuel Swartwout, Burr's lieutenant and main assistant in the conspiracy, who had transmitted a letter in code from Burr to Wilkinson. Swartwout's brother John, Burr's longest-standing assistant, had waited in Burr's home while Burr was shooting Hamilton, and fled New York after the duel to avoid prosecution as a murder accomplice.

Burr met again with Jackson in Tennessee months after the trial. Burr (still under murder indictment) and Samuel Swartwout then went to England. Swartwout made arrangements with the British secret intelligence service's top strategist, Jeremy Bentham, for Burr to live with Bentham while in exile there.

Burr's sponsor, and later Andrew Jackson's most avid international supporter, Bentham had published famous defenses of usury and pederasty. Bentham had written with contempt in October 1776, against the defense of human rights in America's July 4, 1776 Declaration of Independence: "This they 'hold to be' a 'truth self-evident.' At the same time, to secure these rights they are satisfied that Government should be instituted. They see not ... that nothing that was ever called Government ever was or ever could be exercised but at the expense of one or another of those rights, that ... some one or other of those pretended unalienable rights is alienated.... In these tenets they have outdone the extravagance of all former fanatics."

We note that Arthur Schlesinger gushes, "Jeremy Bentham, the great English reformer, confided to Jackson, as one liberal to another, that he [agreed with Jackson's] doctrine of rotation [appointing supporters to public offices]."[17]Burr and Swartwout returned to New York in 1812; Burr's remaining legal difficulties were apparently quietly overcome by Treasury Secretary Gallatin. Swartwout began serving as Jackson's political aide and New York agent. Burr resumed a legal practice, a pioneer in what became the infamous tradition of Wall Street lawyers.

He had been put back into the game by the British Empire's anti-American strategist, Bentham. Burr now sought to turn American politics out of the nationalist consensus, using a front-man, his recent co-conspirator, Andrew Jackson, who was at that time a militia general, being counseled by Burr's aide Swartwout.

The British Army invaded Louisiana in 1815, at the very end of the War of 1812. Their inhuman officers threw the British troops against invulnerable American defenses manned by expert Kentucky riflemen, whose commander was Gen. Andrew Jackson. The resulting slaughter of the British soldiers was the final event of the war, actually following the signing in Europe of a peace treaty, about which the combatants were not yet informed. During the buildup to the Battle of New Orleans, Burr's lieutenant Edward Livingston served as Jackson's aide-de-camp.

|

Library of Congress

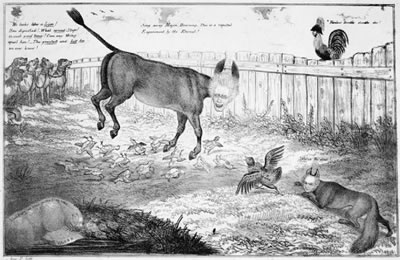

Cartoon for the 1840 election: In President Martin Van Buren’s pouch are opponents of the Bank of the United States Thomas Hart Benton, John C. Calhoun, and Washington Globe editor Francis Preston Blair. The 30-year-old Abraham Lincoln had said in a speech on banking (Dec. 26, 1839), “[It is predicted] that every state . . . will vote [to re-elect] Van Buren. . . . It may be true. . . . Many free countries have lost their liberty. . . . I know that the great volcano at Washington [is] aroused and directed by the evil spirit that reigns there, belching forth the lava of political corruption. . . .” Van Buren lost. |

Alston died soon afterward. But it was Burr's men Samuel Swartwout and Edward Livingston who pushed the Jackson Presidential candidacy over the next few years.

Swartwout continued as Jackson's confidential advisor, and manipulator. He goaded Jackson to attack as a "corrupt bargain," the election of John Quincy Adams and Adams' appointment of Henry Clay as Secretary of State; this became the main point of Jackson's eventually successful campaign for the Presidency.

Jackson as President would appoint Samuel Swartwout Collector of the Port of New York, a very powerful and the most lucrative office the President could award. Swartwout was eventually driven from office on charges of embezzlement. Later Jackson would appoint Livingston Secretary of State.

Van Buren and the Slave Power Bargain

But Jackson's elevation to the White House was only achieved after the Burr clique brought about a newly unified oligarchy, under the management of Martin Van Buren, who was known universally as "the Little Magician," the most cunning, artful intriguer.[19] Van Buren was described as very agreeable and urbane, with impeccable manners, even if he were stabbing someone in the back. An unbeliever, he would attend a politically useful Sunday worship service, dressed in "white duck trousers, snuff-colored broadcloth coat, a tie of brilliant orange, a vest of pearl hue, and yellow kid gloves...."[20]Martin Van Buren, at about age 18, was picked up and initiated into politics by Aaron Burr. In 1801-02, William P. Van Ness, Burr's aide in charge of local political arrangements, took Van Buren into his law office and trained him as an attorney. Burr, then the Vice President, and Van Ness brought Van Buren as apprentice into the New York Tammany Hall organization created by Burr. In 1804, Van Ness served as Burr's intermediary with Alexander Hamilton in making the challenge and securing the fatal duel. Van Ness fled, along with Samuel Swartwout's brother, to avoid prosecution.

Van Buren swiftly ascended to power in New York State, along the way opposing the plan to build the Erie Canal, then shifting to position himself in authority over the canal when its construction proved overwhelmingly popular. He and his followers mocked the 1812 declaration of war against Britain, and tried to whip up a mob spirit against the Madison Administration. Later, when the Federalist Party was dead, Van Buren condemned his opponents as Federalists.

He entered the U.S. Senate in 1821. Van Buren had by then assembled a New York State ruling apparatus nicknamed the Albany Regency, which had many of the trappings of Stalinism a century later. Judges, newspapers, banks, social and political institutions which were not directly controlled by the Regency, must follow the party line or suffer serious consequences. Dissent, breaking "party unity," was an unpardonable offense. Candidates were chosen in closed sessions called "caucuses," and the Regency aimed to direct the appointment or election to every level of public office in the state, down to the smallest local posting. The only real doctrine of the party, was that government will do nothing that might interfere with the interest of Wall Street.[21]Leading this Democracy, the new Senator Van Buren went on the attack against President Monroe. The national unity behind the administration, fed by Monroe's non-partisan appointments and acceptance of former Federalists as allies, was stifling American democracy, Van Buren charged.

Van Buren made his first in a series of trips to the South in March 1822. To counteract the North-South republican alliance, best represented by the politics of Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, Van Buren began seeking a New York-Virginia alliance, based on the power of unbridled aristocracy.

In 1823, he took up a crusade to boost the anti-nationalist, "states' rights" Georgian, William H. Crawford, for President. He also worked to isolate Calhoun from his allies outside the South—to make Calhoun adhere to Southern sectionalism, or be crushed.

Calhoun counterattacked. His staunch allies, Gen. Winfield Scott; Gen. Joseph Gardiner Swift, the former West Point superintendent; and Samuel Gouverneur, President Monroe's son-in-law, founded in 1823 The Patriot, a New York political newspaper devoted to bringing down Van Buren. The Calhoun paper struck at Van Buren's power by demanding a change in New York election law, to allow citizens, not the Van Buren-run state legislature, to vote for the U.S. Presidency.[22] In 1823, Van Buren visited Richmond and secured a union between his organization and that of Thomas Ritchie, leader of the "states' rights" radicals in Virginia Calhoun wrote to Monroe's son-in-law, "Between the Regency at Albany and the junto at Richmond there is a vital connection. They give and receive hope from each other, and confidently expect to govern this nation."[23]Faced with an Adams-Clay Administration and a steamroller of American industrialization, Van Buren sought a vehicle to fundamentally reorient U.S. politics. The means selected was Jackson's military-hero Presidential candidacy, deceptively presented to the public as a continuation of nationalist aspirations, while a contrary, anti-national machine was locked into power behind Jackson.

Van Buren wrote in January 1827 to Thomas Ritchie in 1827, calling for a great political combination "between the planters of the south and the plain Republicans of the North"—the plain Republicans meaning the London-New York financiers' axis. He rebuked the "prejudice" against "the Southern Influence" and against "African Slavery." Van Buren wrote that the "all powerful sympathy" Northerners felt for Southern slaveowners "has been much weakened, if not, destroyed by the amalgamating policy of Mr. Monroe."[24] In April 1827, Ritchie and his Richmond junto accepted Van Buren's plan for a seizure of power behind Jackson. James Monroe, in his first (1817) Inaugural Address, had warned the people never to act as a bestial anti-government mob, manipulated by populist demagogues. Such degradation would lead to the loss of the republic: "It is only when the people become ignorant and corrupt, when they degenerate into a populace, that they are incapable of exercising the sovereignty. Usurpation is then an easy attainment, and an usurper soon found. The people themselves become the willing instruments of their own debasement and ruin. Let us, then, look to the great cause, and endeavor to preserve it in full force. Let us by all wise and constitutional measures promote intelligence among the people as the best means of preserving our liberties...."[25]The populace Monroe warned against, roaring its approval for the people's hero, elected Jackson in 1828. Jackson's managers projected directly contrary images of the candidate to the different sections. The North voted for a protectionist Jackson; the Southern voters chose the states' rights Jackson.

The Jackson Presidency

Martin Van Buren was appointed Secretary of State. Under his guidance, Jackson inexorably moved to break apart the nationalist consensus of the previous era, vetoing Congressional acts for Western transportation projects, and wrecking the Bank of the United States.

Meanwhile Van Buren proceeded to finish off Calhoun, who had been re-elected Vice President after backing Jackson. Van Buren resuscitated an old letter Calhoun had written attacking Jackson's conduct as a general, thus driving Jackson into a revenge-mad fit against Calhoun.

South Carolina's Anglophile establishment, drumming up hysteria over slave revolts and Northern "oppressive tariffs," put Calhoun in a pincers movement. He cracked, and became the main spokesman for a state's right to nullify Federal laws. South Carolina's threat of nullification of the tariff laws was the first serious Southern secession threat.

In this growing crisis, Jackson was steered away from outright disunion by advisors such as Poinsett and Houston. They turned Van Buren's dirty work to good advantage, directing Jackson's personal rage at Calhoun into a positive stance against the threats from Calhoun's state.

On this one count, turning back South Carolina's Nullification, Jackson is blithely denominated a "nationalist"!

But the deal he struck with the South was a severe moral and economic setback for the country. It was agreed that the tariff would in fact be rolled back, to suit the slaveowners and the British.

And to get other Southern states' cooperation, Jackson ordered the Army to evict the Cherokee Indians from land that the United States had guaranteed to them by solemn treaty. Thousands of Cherokees died on the resultant "Trail of Tears," exiled 1,000 miles away to the western wilderness. Georgia rowdies, up-and-coming Masons such as Howell Cobb, demanded the Cherokees' land on the rumor that there was gold underneath it. Georgia's governor ordered the arrest of U.S. government-financed Protestant missionaries who were teaching the Cherokees mathematics, science, and literature. This Indian education program had deeply embarrassed the slave system, which had no public schools even for whites. In the cultural desolation of the South, it gave the slaves a nearby example of intellect and advancement, and it demonstrated that the Southern way of life was anti-Christian.

In his perfidy, Jackson ignored an order of the Supreme Court confirming the treaty rights of the Cherokees. The Chief Executive famously said: It was Justice John Marshall's decision, so let him enforce it—and Jackson slaughtered those who were under his lawful protection. His lifelong racist treachery towards the Indians marked Jackson off sharply from his colleagues Sam Houston and David Crockett, who followed the Benjamin Franklin-George Washington policy of amity and peace.

Jackson was usually a rather loud chauvinist, but his foreign policy was the most nakedly pro-British of any administration up to his time. The first challenge to the Monroe Doctrine came in 1833, when the British Navy seized and Britain occupied Argentina's Malvinas Islands, strategically located in the Atlantic on the route to Cape Horn. Jackson backed the British takeover, and threatened to send U.S. forces to "punish" the Argentines for asserting their sovereignty over the islands, which the British called the Falklands.

The Bank of the United States, which Jackson was to destroy, was the chief instrument for American national resistance to the British Empire and the City of London financial power.

It is chiefly due to Jackson's breaking of the Bank, that academic historians and grossly misinformed populists say that "Andrew Jackson didn't trust the bankers," and "Jackson was for the little people, against the aristocrats."

Congress had chartered the second Bank of the United States (for 20 years) in 1816. Seven years later, in 1823, James Monroe appointed his former diplomatic aide and Latin American intelligence officer Nicholas Biddle as the Bank's president.

Biddle was an outstanding Greek scholar, his Philadelphia family passionate republicans whom Benjamin Franklin had included in his personal "junto."

Biddle had earned appointment as a leading campaigner for re-establishing the Bank of the United States after its original charter had expired in 1811. He explained that without a national bank, working people were defenseless against the usury of the British Empire and its allied financiers:

"Without credit or money, while your commerce is stopped and your manufactures languish ... [in] the total want of money, the demand for specie [coins] will place the poorer classes at the mercy of the rich, and the great money lenders will issue abroad to prey upon their fellow citizens. In the general submersion of small traders, the only beings who will be seen floating on the wreck are those very 'monied aristocrats' whom the [anti-Bank] resolutions denounce with such indignation."[26]Under Biddle's presidency, the second Bank steered the national economy upward, with precision and vigor. Railroads were introduced, with heavy local and state government spending for their construction. The Bank invested in railroads and purposefully bid up the price of their securities. Canal projects, which opened up the West to settlers and brought coal out to create American industry, were backed to the hilt by Biddle's Bank.

When London or Wall Street drove the prices of some commodity too high or too low, Biddle intervened into the market to counteract the speculators, and restore steady growth and prosperity for the producers. Biddle used the Bank of the United States in the same war that Alexander Hamilton had fought, against the international bankers who claimed the right to dictate to the world.

|

Library of Congress

Roger Taney (later the infamous Chief Justice) drew up Jackson’s veto of the rechartering of the Bank of the United States. His role was aptly characterized by Congressman John Quincy Adams in 1834: “Resolved that the thanks of the House be given to Roger B. Taney, Secretary of the Treasury, for his pure and disinterested patriotism in transferring the use of the public funds from the Bank of the United States, where they were profitable to the people, to the Union Bank of Baltimore, where they were profitable to himself.” |

Under the advice of two particular men, Wall Street's Martin Van Buren, and Baltimore slaveocrat Roger Taney, Jackson vetoed the bill to renew the charter for the Bank of the United States, and ordered the removal of the government's deposits from the Bank. These actions ended the protective and nurturing role the Bank had played in the American economy. After the 1836 expiration of the Bank's Federal charter, the Bank of England and British merchants withdrew loans and investments from the financially helpless republic. Jackson also issued an order known as the "specie circular," prohibiting settlers from purchasing public lands with anything but gold or silver. These measures combined to drastically shrink available credit, and threw the country into a chaotic depression-collapse in 1837.

The Bank of the United States, located on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, run by Biddle and the Pennsylvania nationalists, had controlled American credit to the advantage of internal industry, and subdued the influence of the private banker-oligarchs centered in New York. The latter wanted to have all government finances run through a new "government depositary" controlled by Wall Street—just like today's Federal Reserve. Biddle wrote in 1833, that Jackson's war against the Bank was "a mere contest between Mr. Van Buren's government bank and the present institution—between Chestnut Street and Wall Street-between a Faro [card-game] bank and a national one."

The leading American players in the attack on the Bank were

Martin Van Buren, Secretary of State 1829-31, ambassador to Britain 1831, Vice President 1833-37, President 1837-41;

John Jacob Astor, New York slumlord and international fur and opium trader, who had been started in business in London by the British East India Company in the 1780s; Astor was chief owner of the Bank of the Manhattan, founded by Aaron Burr, and later called Chase Manhattan Bank;

Churchill C. Cambreleng, Van Buren's chief lieutenant in the House of Representatives and a paid agent of Astor;

Alexander Brown & Sons, Baltimore and London merchant bankers who got their start serving the enemy British in the War of 1812, and financed 75% of the slave cotton going to England. Brown Brothers Harriman was a later descendant of that firm;

Roger B. Taney (pronounced "tawny"), Baltimore lawyer and banker, U.S. Attorney General 1831-33, Treasury Secretary 1833-34, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (appointed by Jackson) 1836-64;

Thomas Hart Benton, U.S. Senator from Missouri, who got a law enacted overthrowing the government monopoly on the fur trade (instituted by George Washington to protect the Indians and the nation from British intrigues), in favor of the Astor company. Then he became counsel to the Astor company. Benton called the government fur-trade monopoly a "monster," and later called the Bank of the United States a "monster" as well.

Roger Taney drew up Jackson's veto of the Bank recharter. Jackson fired two successive Treasury Secretaries, who wouldn't remove the government deposits from the Bank of the United States. He then appointed Taney, who removed the deposits; Taney put the money into the Union Bank of Baltimore, of which Taney himself was co-owner and chief counsel, into John Jacob Astor's Bank of the Manhattan, and several other "pet banks."

Taney was from the nastiest element of Maryland's Anglophile, fox-hunting, slave-plantation aristocracy, and was a leader of the Boston-run Federalist Party. When John Quincy Adams ran for President in 1824, Taney backed Jackson against him, and went from being a Federalist to a Jackson Democrat without missing a step. In Congress in 1834, Adams skewered Taney with this sarcastic proposal: "Resolved that the thanks of the House be given to Roger B. Taney, Secretary of the Treasury, for his pure and disinterested patriotism in transferring the use of the public funds from the Bank of the United States, where they were profitable to the people, to the Union Bank of Baltimore, where they were profitable to himself." Adams' speech containing this mock resolution was suppressed by the Jackson forces in Congress, so he privately printed it, and Nicholas Biddle distributed 50,000 copies; a copy is in the Library of Congress rare book collection.

This same Roger B. Taney, as Chief Justice in 1857, wrote the Supreme Court's infamous Dred Scott decision. Taney ruled that black people could never be U.S. citizens, and that the slave Dred Scott was not legally free by having gone into the Northwest Federal territories, where Congress had outlawed slavery, because—according to Taney—Congress had no Constitutional power to prohibit slavery in the territories. Abraham Lincoln enraged his opponents by declaring that the Dred Scott decision was part of a "conspiracy" by Taney and other anti-national operatives.

Jackson's Chief Justice Taney, during the Civil War, held that the government had no right to stop the breakup of the Union. Taney worked constantly with pro-Confederate intriguers in Maryland, although that state remained in the Union. He sought the arrest of U.S. military officers, because they were obeying Lincoln's orders to stop saboteurs and spies, but could find no one to serve his writs.

During the Jackson Presidency, a national free-trade movement formed and began holding conferences. This businessmen's movement paralleled and gave doctrine to Van Buren's broader Democratic Party. It combined the various elements of the slave cotton business, from plantation owners, brokers, and factors, to the Wall Street and London financiers, shippers, and insurers. Their main spokesman was former Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin, in his old age the president of the Astor Bank.[27]When Van Buren himself took the Presidency, the Democratic Party of usury and slavery was well entrenched in power. Its popularity was quite variable, however. Van Buren presided over a terrible economic depression, and he was solidly defeated for re-election in 1840 by William Henry Harrison, from Henry Clay's Whig Party. But Harrison died almost immediately after taking office. Again, in 1848, the voters chose a Whig President, Zachary Taylor, but he too died in office, only a year and a half into his term, and his Whig successor, Millard Fillmore, trembled at his fate. Indeed, the deaths of nationalist Presidents would become an almost routine means by which the Anglo-Wall Street axis retained or increased its power.

In the darkening crisis over slavery and the existence of the nation, before the Civil War broke out, Abraham Lincoln attacked this Democratic Party of Van Buren and his successors. He said that, devoted as they were to slavery and to the rule of money, they falsely posed as the heirs of Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence.

Lincoln's own revolution revived that of 1776, and defined American nationality for all time. This was the heritage of President Franklin Roosevelt, who remade the Democratic Party in the 20th Century, and whose legacy must prevail today.

[1] See "Children of Satan III: 'The Sexual Congress for Cultural Fascism,' " EIR, June 25, 2004.

[2] Arthur Schlesinger, Age of Jackson (Boston: Little, Brown, 1946), p. 17.

[3] Ibid., p. 29.

[4] Foster to Wellesley, Dec. 28, 1811, Foreign Office [FO] 5:77, quoted in Bernard Mayo, Henry Clay: Spokesman of the New West (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1937), p. 429.

[5] Foster to Wellesley, Jan. 16, 1812, FO 5:84; quoted in Ibid., p. 469.

[6] Foster to Wellesley, Jan. 31, 1812, FO 5:84; quoted in Ibid., p. 451.

[7] Foster to Castlereagh, May 26, 1812, quoted in Ibid., p. 476.

[8] Jefferson to William Duane, April 20, 1812; quoted in Ibid., p. 475. Duane published the Aurora, a Jeffersonian paper in Philadelphia, ridiculing and exposing Jefferson's Treasury Secretary Gallatin as a foreign agent and conspirator. See Anton Chaitkin, Treason in America (Washington: Executive Intelligence Review, 1985), pp. 82n, 83n.

[9] March 7, 1862, from Hansard's Parliamentary Debates, quoted in James Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress: From Lincoln to Garfield, Vols. I and II (Norwich, Connecticut: Henry Bill Publishing Co. 1884-86).

[10] June 30, 1863, Ibid., Vol. II, p. 480.

[11] Democrats who were otherwise outstanding nationalists included scientific leader Alexander Dallas Bache, Bank of the United States president Nicholas Biddle, German-American economist Friedrich List, and authors Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper and Edgar Allan Poe.

[12] Correspondence of Andrew Jackson, John Bassett, ed., (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution, 1926-35), Vol. 1, p. 16.

[13] Ibid., p. 17.

[14] Quoted in Burke Davis, Old Hickory: A Life of Andrew Jackson (New York: The Dial Press, 1977), p. 19.

[15] Merry to Harrowby, Aug. 6, 1804, taken from the British archives in the late 19th Century and quoted in Henry Adams, History of the United States of America in the First Administration of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1921) Vol. II, p. 395.

[16] Davis, op cit., footnote 14, p. 51.

[17] Schlesinger, op cit., footnote 2, p. 46.

[18] Burr to Alston, Nov. 29, 1815, quoted in Milton Lomask, Aaron Burr: Conspiracy and Years of Exile, 1805-1836 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1982), pp. 366-367.

[19] Frontier political leader David Crockett, who was to die at the Alamo, wrote that Van Buren was appropriately caricatured in his day as "half fox and half monkey, [or] half snake and half mink, [the cartoonists] designating him by some animal that most resembled his traits of character." David Crockett, The Life of Martin Van Buren (New York: Nafis & Cornish, 1845), p. 101. Crockett contrasts the manipulable, revenge-mad Jackson and the calculating Van Buren.

[20] Robert V. Remini, Martin Van Buren and the Making of the Democratic Party (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959), p. 190.

[21] Van Buren initiated a law to insure the banks in the state, a "government interference" which supported Wall Street's power.

[22] This election reform was finally adopted over Van Buren's opposition, but the Albany Regency continued to rule New York through the 1820s and 1830s. For the anti-Van Buren paper The Patriot, see Anton Chaitkin, "The Patriot Files, Unearthed," EIR, Oct. 27, 2007, www.larouchepac.com/files/pdfs/patriot_file_unearthed.pdf.

[23] Calhoun to Samuel Gouverneur, Nov. 9, 1823, quoted in Remini, op cit., footnote 20, page 41.

[24] Van Buren to Thomas Ritchie, Jan. 13, 1827, Ibid., pp. 131-132.

[25] The Inaugural Addresses of the Presidents (New York: Gramercy Books, 1997), page 53.

[26] Speech to the Pennsylvania Senate, Jan. 8, 1811, quoted in Thomas Payne Govan, Nicholas Biddle: Nationalist and Public Banker, 1786-1844 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959), pp. 31-32.

[27] Not to be confused with John Jacob Astor's other enterprise, the Bank of the Manhattan, in which Astor merely held a controlling interest.