The Science of Happiness

by Andrea Andromidas

May 2017

A PDF version of this article appears in the January 13, 2017 issue of Executive Intelligence Review and is re-published here with permission.

View full size

Wikipedia Commons |

Three hundred years ago, the great thinker Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz died on November 14, 1716. As he was carried to his grave, his faithful servant Eccard followed the coffin. All the others for whom he had worked, especially the members of the court of Hanover, did not care much. The Prussian Court in Berlin and the Prussian Academy of Sciences also took no notice of the death of their founder and first president.

And yet, only sixty years later, one of the central ideas of Leibniz, the “science of happiness,” had acquired such a significance that it was included in the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”[1]

More than 200 years later, all this has been forgotten. Neither in America nor elsewhere in the Western world does anyone have an idea of what the pursuit of happiness has to do with the constitution of a state, nor what would be understood in Leibniz’s sense. Happiness? According to Heidi Klum’s definition, this would mean sex, champagne and chocolate, while others might add money or change the order. Because this is so, let us talk about the great significance for the founding fathers of this Leibnizian idea and why they felt that it applies to all the future—including the newly elected President Trump, for example, whether he knows it or not.

Leibniz’s Optimism

That the idea of happiness is more than a temporary feeling of well-being is shown by the fact that Leibniz not only spread the concept during the confused period after the Thirty Years’ War, but he also connected it to the concept that we live in the best of all possible worlds. Leibniz was born in 1646, two years before the end of the Thirty Years’ War, amidst the greatest devastation imaginable. After the Peace of Westphalia had finally been achieved, the result seemed rather gloomy: Germany had lost a third of its population, towns and whole lands were heavily marked by the war, science and education had fallen pathetically. Atheistic ideas sprouted like mushrooms and pessimistic conceptions of mankind were commonplace.

But Leibniz was extremely fortunate not to be a child of his time. After the early death of his father, at the age of eight, he was given the key to his library. Thanks to his unusual interest and his extraordinary talent, he was able from this time onwards, in addition to his schoolwork, to become acquainted with the views and arguments of the various philosophers, the old as well as the new, completely unaffected by the tastes of his time. During this time he formed a special, lifelong friendship with Plato. Even before he received his high school diploma and entered the university, he had so appropriated Plato’s method of thought that he always responded to the arguments of his contemporaries with this perspective. Among the celebrated contemporaries were some of those still widely quoted today, such as Newton, Locke, Hobbes, and Descartes.

What most provoked Leibniz’s contemporaries was his imperturbable optimism. How could this thinker, in a time of the greatest external and internal devastation, be able to assert with full conviction that we lived in the best of all possible worlds? How could he assert that happiness is more than a subjective feeling, and that there is even a science of happiness, and that the pursuit of happiness must become the social goal of all men?

I would argue that the concept which underlies these statements seems just as unusual, if not even more alien, to people of our time as it did to people living after the Thirty Years War. The optimism of Leibniz is connected with the conviction that the cognitive capacity of man occupies such an important place in the cosmos that the best of all worlds is inconceivable without it.

This idea seems so strange to our contemporaries, because we live in a time that degrades man more and more. Already in kindergarten it is taught that people consume undue amounts of raw materials, pollute the earth, poison the climate, destroy the planet. It is not unusual to hear the assertion that man is an accident of evolution, that there are already too many of us, especially in Africa, and above all in China, and that in the near future, perhaps after a couple of million years, human beings will vanish once again.

With the degradation of man, the will and the courage for the attainment of knowledge also disappear. Even scientific concepts which were long ago considered mastered are forgotten, buried, or thrown on the scrap heap. One of these devastated areas is economics, which I shall discuss. Regression is passed off as an advance because scientific concepts are replaced by ideologies, esoteric phantasies, untested experiential conclusions, and ever-changing currents of views and opinions, which are appropriately mixed and evaluated according to fashion and are looking for new adherents in daily talkshows in the marketplace of ideas.

There are more than a few who want to escape this confusion, who support ethics commissions for the financial market, moral economics, and equitable coexistence. This also shows the uniqueness of human existence, that at least the longing for truth and justice does not perish in the greatest chaos, even if the path to fulfillment is unclear. Even in Leibniz’s lifetime, it was not clear what the good actually was.

Leibniz says, “But since righteousness leads to the good, and wisdom and goodness, which unite to form righteousness, refer to the good, then one will ask what is truly Good. I reply that it is nothing more than what serves the purpose of the perfecting of rational substances.”[2]

It must be clearly stated in our era of mental laziness: Leibniz was convinced that there can be no real good without the promotion and perfection of human cognitive ability.

The Establishment of Academies

His lifelong endeavors for the establishment of academies therefore served the purpose of the development of this gift of reason, which finds expression in the perfection of the cognitive capacity of man. Leibniz, with Plato, Nicholas of Cusa, and many others, felt that this capacity of knowledge can not be content with empirical experience alone, and can not refer only to what we see or feel. They were of the opinion that man can do much more, that he must abandon the narrow limits of the sensible world and ascend to the region of knowledge if, as Plato puts it, he wants to look at the eternally existing instead of the becoming, to that which is not subject to chance and opinion, but is of eternal validity. At the time of the Humboldts, a period which was directly influenced by Leibniz’ academy movement, this not so easily grasped idea was quite widespread. In his lectures on the cosmos, Humboldt describes how problematic opinions can be when they are only based on empirical observations, or merely spring from feelings:

“From incomplete observations and even more incomplete induction, erroneous views arise on the essence of the forces of nature, views which are embodied, so to speak, in important language forms, and assume the shape of a shared fantasy which spreads throughout all classes of a nation. Next to the scientific kind of physics, another system is formed, a system of untested, partly misunderstood empiricism. Comprised of a few details, this kind of empiricism is all the more presumptuous, as it knows of no facts that might shake its conviction. It is self-contained, unchanging in its axioms, presumptuous like everything that is limited.”

On the other hand, according to Humboldt, man, in accord with to his sublime destiny, is called upon “to grasp the spirit of nature which is concealed under the cover of phenomena. In this way, our endeavor extends beyond the narrowness of the sensory world, and we can succeed in grasping Nature, in mastering the raw material of empirical intuition, as it were, through ideas.”[3]

The Cosmos

As Reference Point

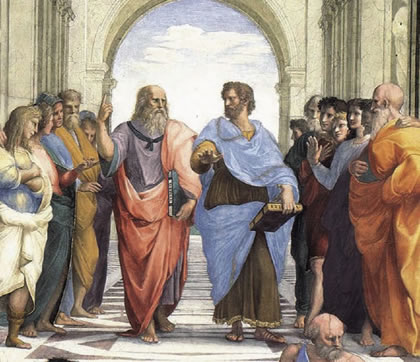

View full size

Wikipedia Commons

Detail from Raphael’s “The School of Athens.” |

In the plan for the founding of an Academy of the Arts and Sciences in Germany, Leibniz at the outset shows that the cosmos of man must be the point of reference: “The knowledge of divine nature can, of course, be taken as nothing other than the true demonstration of its existence. Such must be brought about chiefly by the fact that without it, it is not possible to have a cause (since there is nothing without cause) for why the things which could not be, nevertheless are; and further, why the things that might be confused and confused are present in such a beautiful, ineffable harmony.”[4]

The idea of the harmonious, ordered universe, the idea of the best of all worlds, comes from Plato’s dialogue Timaeus. Because Leibniz gave this idea such central importance in his academy movement, I would like to quote a passage from the Timaeus:

“Inasmuch as God wished that all things should be good, and, as much as possible, nothing bad: when he found the visible world not at rest, but rather in unseemly and random motion, he brought it from disorder to an order that appeared far better to him. But the best could never be anything other than the most beautiful; concluding, therefore, according to his nature, with the Visible, he found that nothing that omitted the faculty of thought, as a whole, would ever be more beautiful than one endowed with reason as a whole, which would be impossible unless the soul were blessed with reason. Operating from this conclusion, he gave the soul reason and to the body gave the soul, and formed the universe out of it, so as to complete the most beautiful and best work according to his nature.”[5]

The order of the universe must therefore be the reference point of man. Unlike animals, man can recognize this harmony, never fully, but step by step, in a continuous process of perfection. And he can do more, he can bring his own deeds into harmony with this universe. And because the young United States of America designed its program with this intention, to direct its own deeds according to the order of the universe, the founding fathers wrote into the Declaration of Independence the right to strive for happiness. It does not mean that one will create paradise on earth, but it means that through all storms one is obliged to serve the common good, or in other words, to contribute to the progress of all humanity, even to the development of the entire cosmos.

From this never-ending mission, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz drew his imperturbable optimism. His academies and learned societies, as he pursued them from his youth up to the end of his life, were to gather, educate, form, and put into the service of the one human race the entire religious, intellectual, scientific and economic potential of the people, and to further their process of growth and maturity. In a letter to Peter the Great from 1712, he wrote:

“I am going for the benefit of the whole human race, and I am more inclined to achieve something good with the Russians than with the Germans or other Europeans, for my inclination and pleasure go to that which is best for all.”

To love God means to promote public well-being and to realize universal harmony, as far as one can contribute to it, “for God has created the rational creatures for no other purpose than to serve as a mirror, wherein His infinite harmony would be reproduced in infinite ways,” as he put it in the founding publication of his academy.

This idea was followed by the founding fathers of the United States of America, when, in addition to the right to life and liberty, they also asserted the right to pursue happiness.

Have they ever realized it? Yes, in certain periods, under Presidents Lincoln, Quincy Adams, Franklin Roosevelt, Eisenhower, and Kennedy, whenever the struggle against the influence of the British oligarchy was won—whenever the credit system created by Alexander Hamilton was put into the service of real economic development.

Without fail, when the development of the intellectual abilities of the population became the focus of social life, science and art flourished, and industry made extraordinary progress. America had several periods of gigantic ingenuity and growth, one between 1820 and 1830, then between 1860 and 1880, and later still the period of electrification and the space program.

In a manner similar to that of China today, the railway lines, canals, ports and cities, dams and power stations grew. In the cities, public libraries, schools and universities, symphony orchestras and opera houses were built. America became the land of hope for immigrants from all over the world and a catalyst for progress in other parts of the world as well. In these better periods of America, the Leibnizian idea that the wealth and freedom of a country would increase with the mobilization of the creative abilities of its citizens was indeed put into practice. Not for nothing was this America a beacon of hope.

For a New Academy Movement

View full size

NARA

Eleanor Roosevelt at Works Progress Administration site in Des Moines, Iowa. |

The America we have known in the twenty-first century to date is not the America which took up the cause of the pursuit of happiness, at least not in the sense that Leibniz understood it. The America we have known in the twenty-first century to date has long lost the mandate of heaven. The greed for the fast money determines the system, and only those who join in without scruple can be full participants. At the heart of all considerations is not the mental capacity and the creativity of the population, but simply Mammon. A collapse of literacy and a wave of drug abuse are spreading, whole industries are rusting, and once great cities are disintegrating.

The outgoing president waged seven wars, and the devastation there was akin to that of the Thirty Years’ War.

But we still live in the best possible of all worlds. And as well, the desire for the pursuit of happiness has not disappeared. The richness of invention is today celebrated at the other end of the world, in Asia. New cities are now emerging there, thousands of kilometers of highways, ports, bridges and space programs are being created. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz already recognized 300 years ago that the culture of the Chinese contained this same, universal idea, that the concept of the “mandate of heaven” was nothing other than the “pursuit of happiness.”

Subscribe to EIR Daily Alert Service  |

“I think of heaven as the fatherland, and of all the beneficent people as His fellow-citizens,” he wrote in the letter to Tsar Peter the Great cited above.

From all this we can only conclude that we need an academy movement which restores man’s capacity for knowledge to its proper place—this time, to enable mankind to strive for happiness.

Finally, a quote from Alexander von Humboldt, from the lectures on his cosmos:

“Man cannot act upon nature, he can not acquire any of her powers, if he does not know the laws of nature according to terms of measure and numbers. Here, too, lies the power of the popular intelligence. It rises and falls with this. Knowledge and understanding are the joy and the justification of humanity.”

[1]. From the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America, 1776, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_

Declaration_of_Independence#Annotated_text_of_

the_engrossed_Declaration and Fidelio Article—From Leibniz to Franklin on ‘Happiness’

[2]. Leibniz: “Von der Allmacht und Allwissenheit Gottes und der Freiheit des Menschen,” 1670, see: http://dokumente.leibnizcentral.de/index.php?id=96

[3]. Alexander von Humboldt: “Einleitende Betrachtungen über die Verschiedenartigkeit des Naturgenusses und eine wissenschaftliche Ergründung der Weltgesetze.” (Vorgetragen am Tage der Eröffnung der Vorlesungen in der großen Halle der Singakademie zu Berlin.) In: Kosmos. Entwurf einer physischen Weltbeschreibung, see: http://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/book/view/humboldt_kosmos01_1845?p=22

[4]. Leibniz: “Grundriß eines Bedenkens von Aufrichtung einer Sozietät in Deutschland,” 1671, see https://leibniz.uni-goettingen.de/files/pdf/Leibniz-Edition-IV-1.pdf, S. 530 ff.

[5]. Plato, Timaeus, see: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/timaeus.html