Your Musical Pathway from Dark Age Thinking

to a Classical Renaissance

by Philip Ulanowsky

October 2015

Oct. 19—The Presidential candidates’ debate had begun; Having finished introductory remarks, the host now focused on the candidates. Tens of millions like you watched expectantly.

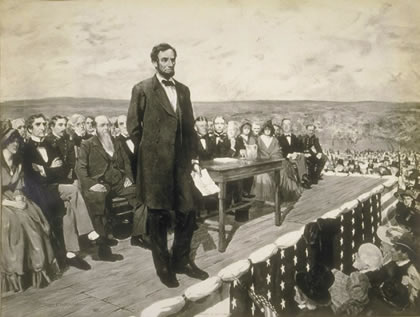

Library of Congress

A Classical Standard: Abraham Lincoln delivers his Gettysburg address at the dedication of the National Cemetery there on Nov. 19, 1863. |

“Our first question tonight: How do you view the last half-century of cultural degeneration due to the rise and predominance of rock music, and, if elected, how do you propose to reverse it?”

Think twice before dismissing this fictional occurrence, and think carefully. Clearly, it bears no resemblance to any Presidential (or other government office) debate in the referenced half-century to date—though America has in its older experience, times when issues of similar cultural depth consumed the public interest. Today’s serious citizen, of any persuasion, can find in the writings and speeches of inspiring earlier leaders in politics, science, and arts, language of conceptions born of an elevated mind, informed by the Classics. These were the ideas, presented to the public, upon which rested our greatest achievements in economic development, statecraft, scientific exploration, and technological advance.

Yet, who among those leading minds faced a global, civilizational moment as grave as ours? Who, despite the terrible ignorance and backwardness in many parts of the citizenry of their times, had to contend with a rock-music-brutalized population of several generations that would fight to defend its degeneracy, but not to free itself to participate in rescuing its own nation, descending from increasing illiteracy into a barbarism proud of the depravity of its self-entertainment?

Rediscovering Beauty

To escape from the jaws of today’s collapse, no mechanistic solution can succeed. The best program for economic revival must fail, unless we raise ourselves to wrestle with the uncomfortable reality that our own departure, over decades, from the truly creative in the sciences and arts alike, has “done us in.” For various reasons, the most accessible pathway out of deadly, dark-age thinking for today’s serious citizen, is a rediscovery of the beauty the Classical school of musical science presents to the mind.

In 1962, a leading Twentieth-Century Classical musician made some prescient remarks in his commencement address to an American conservatory’s graduating music students. Accompanist Paul Ulanowsky (1908-1968), world renowned as a pianist, coach, and teacher, recalled his own youth in Austria, when “there was no TV then, of course; radio was not even in the crystal set stage; the record or rather phonograph industry concentrated on opera singers, with Caruso and Galli-Curci leading the field . . . and this, except for opera and public concerts, WAS IT. The music lover outside the larger cities therefore had to become a Do-it-yourself-addict, from sheer necessity.” He followed this thought, referring to the increasing intrusions of instant electronic entertainment:

If there is one thing which makes me nostalgic for that legendary state of affairs, it is that people used to put a different value on music. We live in a time and culture where its presence or absence is determined by the pushing of a button or the turning of a knob. It haunts and hounds us in restaurants and rest rooms, in elevators, stations, on trains and planes, in addition to other more conventional premises, at work and at leisure. This has inevitably led to a revision of the status of music in our civilisation and to a reappraisal which on occasion becomes agonizing in the truest sense of the word.

And this, decades before today’s plague of ever-present personal listening devices had gripped an already increasingly asocial society. Could this process have contributed to your acceptance of today’s degraded substitutes for your active participation in setting the nation’s future course? Put it another way: What do you seek in your daily life that offers the quality of universal thought in which you may see reflected your own creative potential to grasp those vital conceptions needed to launch a new renaissance?

A Renaissance? txt me

creative commons/Tomwsulcer

A Renaissance? txt me |

As the seminal figures of Europe’s Florentine Renaissance reached back to Ancient Greece for the ideas upon which to build a new society from the consequences continued from the Roman Empire’s folly, so today we may look, also, to the highpoints of Western thought and culture before our present time. We will find the ideas we need in Classical musical science.

The perplexity of the very term “musical science” owes to the degeneration we must use great art to reverse. Leonardo da Vinci, the universal thinker, would have laughed at the question, “Which are you, a scientist or an artist?” The great Albert Einstein found the inspiration to overcome obstacles in his work by turning to his cherished violin; he was an accomplished Classical musician (as many of his leading predecessors had been). This was no escape to “feel good” music, no “easy listening” or “oldies favorites,” let alone, of course, some guitar-smashing Dionysian abandon or mind-numbing repeated beat and rhythmic monotone rhyming. But, where, then, are “scientific ideas” in Classical music?

Admittedly, for the majority of today’s public, who have been robbed of adequate opportunity to sing in a Classical chorus or perform in a similar instrumental ensemble, some introduction to the proverbial lay of the land is needed, something beyond the compass of this brief article—and far better discovered in a live, participatory setting. We can, however, say a few things here.

Where singing is involved, the Classical composers reflected, and often enhanced, the central irony of the chosen poem, Biblical text, or dramatic script (as in opera), by employing the various features of music to this end. These features are already known to everyone from ordinary speech.

You can, right now, conduct a little experiment, a musical one, to demonstrate your own knowledge of this, with this sentence. Read the sentence aloud, but remove the music from it—changes in pitch (keep your voice a dead monotone); in tempo (speed); in rhythm (different lengths of syllable or lengths of pauses between them); in accent (for instance, no accent on the second syllable of “experiment”); in tonal quality (harsh or soft, for example); in dynamics (loudness). Making sure to keep your voice unnaturally at exactly the same pitch throughout, you may enunciate either without any space in-between syllables (including between words) or with exactly the same length of break between all syllables, thus:

You-can-right-now-con-duct-a-lit-tle-ex-per-i-ment-a-mu-sic-al-one-to-de-mon-strate. . . .

Becoming conscious of how the music behind the words determines their meaning, can be an important discovery in itself, and offers a window into the way a poem’s or play’s idea may be enhanced by adding one or more “voices” in the musical accompaniment to which it is set, an accompaniment that provides not merely a background to the words but an intimately interwoven feature of expressing the idea behind them. In some cases, changing the music of speech can impart the opposite meaning of the words themselves—an irony through “tone of voice.” Coming to recognize and enjoy this interplay, however, is made difficult by addiction to virtually constant background music as entertainment, so easily pursued today.

In the same speech quoted above, Ulanowsky added something to his previous comment, after discussing the music teacher’s role:

But there is something even more basic than exercise [of voice or instrument], something which is often overlooked in the pressures of a professional curriculum heavy with technique and literature. That is the meaning and value of Silence. Not just the measured silence of the rests between phrases and movements [of a piece], but that blessed primal silence which first created the need for sound.

This seems to me particularly essential at a time when we must compete in our music making with automobiles, dishwashers and other such gadgets. More than ever we must remind ourselves and others that music needs this inner silence and poise of listener and player alike.

Classical music, like a Shakespeare play, demands something of us to give forth its riches.

Where do we find ideas in music without singing, leaving us without words to guide our thoughts? Actually, music gains greater freedom to express universal ‘scientific’ ideas. Not, of course, if we accept the false prevalent, inculcated notion that scientific means mathematical or merely logical in the strict sense; instead, when science refers to discovery of provable principles of nature, including man, as the greatest scientists and artists (and, importantly, theologians) have understood it. As in communication in words or two-dimensional imagery, the language of music may present its own ironies—ambiguities or problems to be solved—and make its way to a resolution which the mind comprehends, just as the same mind may seek to resolve ambiguities and problems in science per se and other branches of knowledge. Art that is not merely “decorative,” but enlivens and enriches the genuine creative faculties of artist and audience alike, serves the greater purpose of mankind in shaping the future.

The Gifts of Song

The composition, proper performance, and full appreciation of great music is not entirely easy, and indeed, much of the Classical musical singing literature reaches its pinnacle in the works of foreign composers—Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Verdi, and others—writing in languages other than English. Nonetheless, it is accessible and a pursuit which has formed a core of the LaRouche movement since its early days in the late 1960s, when Lyndon LaRouche, looking out at a sea of American college youth being seduced by a new fascist movement in the guise of “freedom” from Classical ideas, industry, and scientific progress, and “freedom” to sink into and spread existentialism and the rock-drug-sex counter-culture, determined, by himself, to create the germ of a new renaissance.

There is a rich record of Classical musical performance by those such as Ulanowsky and many others of his generation, whose intimate knowledge of, and passionate commitment to presenting faithfully, the ideas of some of the greatest minds in science and art, stands ready to inspire us. In such recorded performances, one may discover the striking difference between what we might call masterful storytelling, and the pathetic performance of a candidate repeating short phrases to incite animal calls from the audience. The difference between that which can rescue our humanity and that which defiles it.

paul-ulanowsky.com

Paul Ulanowsky accompanying Danish tenor, and later bass, Aksel Schøtz in rehearsal for a Lieder album, after the singer’s recovery from a stroke. |

To face the full reality of today’s global collapse—the exciting positive developments of the BRICS and allied countries notwithstanding—requires a quality of personal courage needful of deep wellsprings and frequent refreshment. Classical music offers a personal emotional and intellectual connection to the great creative minds of the past, to the universal ideas they embraced, to the place in each of us where they resonate. The devaluation of the innate, uniquely human spark of divine creativity, the devaluation of human society which our youthful generations accept as simply normal, reaches each of us personally; the horrors in the daily news lie not merely outside ourselves as something we view as spectators at some sort of modern Roman Circus.

Within the works bequeathed us by the great Classical poets and composers, lies a treasure of beauty of a special kind, a kind in which we may find a reflection of that within ourselves which is most noble, from which to find the courage to change ourselves, to participate in the best of humanity, so that we may replace the rotting core of our dying nation with new spirit to attain the role America’s founders wished for the republic so hard won from the brutish impositions of the British Empire then. As the great scientist Benjamin Franklin, emerging from the Constitutional Convention, answered to someone asking what kind of government had been created: “A republic, madam, if you can keep it.”

If you wish to restore it today, don’t look to a person or program from the outside, but to rejection of rock and its companions in irrationality, and relighting the lamp of Classical music, from within.

Philip Ulanowsky is the son of Paul Ulanowsky. More about the latter can be learned at the website paul-ulanowsky.org.