Two Speeches

on the Occasion of the 150th Anniversary

of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address

November 2013

To mark the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, two speeches are reproduced here. The first is the speech made by former President Dwight Eisenhower on November 19, 1963 in Gettysburg, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Lincoln's remarks. President Kennedy, who had visited Gettysburg with his family in the Spring, had been invited to return on November 19, but he regretfully declined the invitation, citing prior commitments that he had to fulfill in Dallas. The elevated tone, the poetic character, the substantive subject, and the relative brevity of Eisenhower's speech are testaments to the enduring impact that Lincoln's Address had on the institution of the Presidency. Great Presidents, and those who aspired to greatness, ennobled themselves and their administrations by reflecting on Lincoln's poetic vision of the future, as that was articulated in his Gettysburg Address.

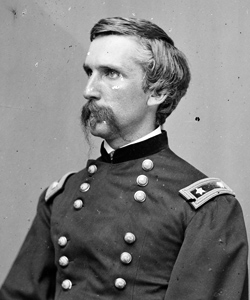

The second citation consists of portions of a speech delivered by General Joshua Chamberlain (ret.) on October 3, 1888, on the occasion of the dedication of a monument to the soldiers of the 20th Regiment of Maine, who had fought so courageously at Gettysburg. As a Colonel, Chamberlain had led the 20th Maine to an heroic defense of Little Round Top on July 2, 1863, and thereby secured the Union's vulnerable left flank. He was personally awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions. An important part of his speech was devoted to the lofty ideas and spirit that motivated the soldiers of the Union to accomplish such great deeds.

(For more in commemoration of Gettysburg, see Steve Douglas's article "Lincoln, JFK, Gettysburg, & The War Against Wall Street," in EIR, Nov. 22, 2013. Coming soon to larouchepub.com)

First President Eisenhower:

We mark today the centennial of an immortal address. We stand where Abraham Lincoln stood as, a century ago, he gave to the world words as moving in their solemn cadence as they are timeless in their meaning. Little wonder it is that, as here we sense his deep dedication to freedom, our own dedication takes added strength.

Lincoln had faith that the ancient drums of Gettysburg, throbbing mutual defiance from battle lines of the blue and the gray, would one day beat in unison, to summon a people, happily united in peace, to fulfill, generation by generation, a noble destiny. His faith has been justified — but the unfinished work of which he spoke in 1863 is still unfinished; because of human frailty, it always will be.

Where we see the serenity with which time has invested this hallowed ground, Lincoln saw the scarred earth and felt the press of personal grief. Yet he lifted his eyes to the future, the future that is our present. He foresaw a new birth of freedom, a freedom and equality for all which, under God, would restore the purpose and meaning of America, defining a goal that challenges each of us to attain his full stature of citizenship.

We read Lincoln's sentiments, we ponder his words — the beauty of the sentiments he expressed enthralls us; the majesty of his words holds us spellbound — but we have not paid to his message its just tribute until we — ourselves — live it. For well he knew that to live for country is a duty, as demanding as is the readiness to die for it. So long as this truth remains our guiding light, self-government in this nation will never die.

True to democracy's basic principle that all are created equal and endowed by the Creator with priceless human rights, the good citizen now, as always before, is called upon to defend the rights of others as he does his own; to subordinate self to the country's good; to refuse to take the easy way today that may invite national disaster tomorrow; to accept the truth that the work still to be done awaits his doing.

On this day of commemoration, Lincoln still asks of each of us, as clearly as he did of those who heard his words a century ago, to give that increased devotion to the cause for which soldiers in all our wars have given the last full measure of devotion. Our answer, the only worthy one we can render to the memory of the great emancipator, is ever to defend, protect and pass on unblemished, to coming generation the heritage — the trust — the Abraham Lincoln, and all the ghostly legions of patriots of the past, with unflinching faith in their God, have bequeathed to us — a nation free, with liberty, dignity, and justice for all.

Here follow the remarks of Joshua Chamberlain:

...We fought no better, perhaps, than they. We exhibited, perhaps, no higher individual qualities. But the cause for which we fought was higher; our thought was wider.... We took rank by its height, and not of our individual selves.

It is something great and greatening to cherish an idea; to act in the light of truth that is far-away and far above; to set aside the near advantage, the momentary pleasure; the snatching of seeming good to self; and to act for remoter ends, for higher good, and for interests other than our own.

Our personality exists in two identities,—the sphere of self, and the sphere of soul. One is circumscribed; the other moving out on boundless trajectories; one is near, and therefore dear, the other far and high, and therefore great. We live in both, but most in the greatest. Men reach their completest development, not in isolation nor working within narrow bounds, but through membership and participation in life of largest scope and fullness. To work out all the worth of manhood; to gain free range and play for all specific differences, to find a theatre and occasion for exercise of the highest virtues, we need to widest organization of the human forces consistent with the laws of cohesion and self-direction. It is only by these radiating and reflected influences that the perfection of the individual and of the human race can be achieved.

A great and free country is not merely defense and protection. For every earnest spirit, it is opportunity and inspiration. In its rich content and manifold resources, its bracing atmosphere of broad fellowship and friendly rivalry, impulse is given to every latent aptitude and special faculty. Meantime enlarged humanity reflects itself in every participant. The best of each being given to all, the best of all returns to each. So the greatness as well as the power of a country broadens every life and blesses every home. Hence it is that in questions of rank, of rights, and duties, Country must stand supreme.

The thought goes deeper. There is a mysterious law of our nature that, in this sense of membership and participation, the spirit rises to a magnitude commensurate with that of which it is part. The greatness of the whole passes into the consciousness of each; and the character of the whole seems to become the power of each; and the character of the whole is impressed upon each. The inspiration of a noble cause involving human interests wide and far, enables men to do things they did not dream themselves capable of before, and which they were not capable of alone. The consciousness of belonging, vitally, to something beyond individuality; of being part of a personality that reaches we know not where, in space and time, greatens the heart to limits of the soul's ideal, and builds out the supreme of character.

It was something like this, I think, which marked our motive; which made us strong to fight the bitter fight to the victorious end, and made us unrevengeful and magnanimous in that victory....

Every man felt that he gave himself to, and belonged to, something beyond time and above place,—something which could not die.

These are the reasons, not fixed in the form of things, but formative of things, reasons of the soul, why we fought for the Union....

In great deeds, something abides. On great fields, something stays. Forms change and pass; bodies disappear; but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls. And reverent men and women from afar, and generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field, to ponder and dream; and lo! The shadow of a mighty presence shall wrap them in its bosom, and the power of the vision pass into their souls.

This is the great reward of service. To live, far out and on, in the life of others; this is the mystery of the Christ,—to give life's best for such high sake that it shall be found again unto life eternal.

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate -- we can not consecrate -- we can not hallow -- this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us -- that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion -- that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain -- that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom -- and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Abraham Lincoln November 19, 1863