The Multiple Dimensions of China’s ‘One Belt One Road’

in Uzbekistan

by Ramtanu Maitra

February 2017

Dec. 27—To seek a single purpose behind China’s launch of its One Belt One Road (OBOR) project, would be as futile an exercise as that of the proverbial “six blind men of Hindustan,” who attempted to describe the shape of an elephant. Some claim that Beijing’s objective is to supply the want of transportation infrastructure that has prevented free movement of people and freight across the vast Eurasian landmass, divided long ago into Asia and Europe. That is true, but only partially so because, as others point out, the OBOR, in its fully developed form, will also provide energy, manufacturing, and cultural exchange, all key ingredients for society’s progress and security. According to the trade journal Supply Chain 24/7,

While China has invested heavily in infrastructure in recent years, investment in manufacturing has now accelerated. Beijing’s aim is to upgrade its domestic industry by internationalizing it. Manufacturing outsourcing more than doubled in 2015 with machinery manufacturing increasing 154 per cent.[1]

Considering the impact of OBOR on Uzbekistan, it seems the second group of “blind men” has the advantage over the first in their quest for the complex answer. In other words, China’s role in Uzbekistan does not center around running a railroad from China to Uzbekistan, but in strengthening Uzbekistan’s still fragile industrial base. Of equal importance are the efforts by both nations to reestablish the old and virtually forgotten cultural linkages and develop a new linkage in science and technology.

The Historical Trade Routes

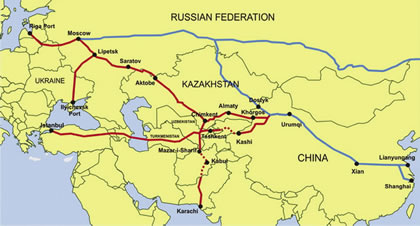

View full size

The rail links from China to and through Central Asia. The proposed segment across Kyrgyzstan, from Kashi to the Uzbekistan border near Tashkent (a dashed line), is in political limbo. |

More than 2,000 years ago, at least two of the numerous trade routes across Asia passed through what is today Uzbekistan. Caravans of hundreds of Bactrian camels, often led by Sogdian merchants, would wend their way to and from China, India, and what today we call the Middle East. From China, bolts of silk went westward from about 100 B.C. to 1500 A.D. The routes and modes of conveyance were many. This web of routes that we call the Silk Road could just as easily have been described as—

a ‘Lapis Lazuli Road’ from Afghanistan to Egypt and India, a ‘Jade Road’ from Khotan to China, an ‘Emerald Road’ stretching east and west from the Pamir mountains of Tajikistan and Afghanistan, or a ‘Gold Road’ or ‘Copper Road’ to the capitals of the Middle East.[2]

In the past, great Uzbek cities such as Tashkent (known as Chash, then), Ferghana (Farghona), Samarkand (Samarqand), Bukhara (Bukhoro), Khiva, and Termez emerged along these trade routes. These were then the international transshipment points, the vital centers of trade, skilled craft work, and cultural exchange, even while political rule of the region shifted from the Iranian Sogdians to the Islamic Caliphate, and then to various embodiments of Mongol and Turkic rule. Uzbekistan was absorbed into the Russian Empire in the 19th Century and became part of the Soviet Union.[3] This history is reflected in the Uzbek language, a Turkic language with influences from Persian, Arabic, Tatar, and Russian.

Uzbekistan, China, and Russia Today

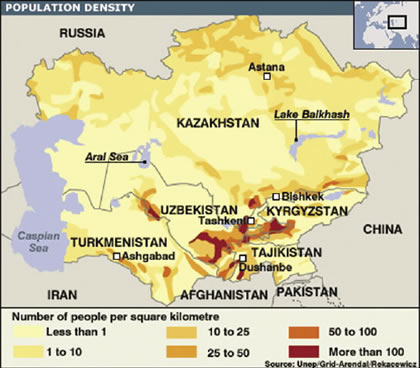

View full size

UNEP

Population density map for Central Asia. |

Today, Uzbekistan is a nation of 30 million. The vast majority live in the eastern and southern part of the country; the vast arid zone of central and western Uzbekistan virtually uninhabited.

As during the golden age of Central Asia—7th to 14th centuries—Uzbekistan’s bilateral trade with China to the east remains crucially important. In the first decade following Uzbekistan’s independence in 1991, the value of its annual trade with China did not exceed $140 million. It gained momentum in the early 2000s and amounted to $4 billion in 2015 (20% of its total international trade).

China’s One Belt, One Road initiative is now interlinked with Uzbekistan’s model for economic development. China has promised investments in railroads, roads, tunnels, and other transportation projects. Some of these projects are already complete.

Throughout the Central Asian region—that is, east of the Caspian Sea—the OBOR, in conjunction with Russia to the north, is playing an important role, fortified in the recent years by the formation and strengthening of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), an organization that includes four of the five Central Asian countries and is led by Russia and China. (The fifth, Turkmenistan, currently attends SCO meetings as a guest.)

Since the early 1990s, following the demise of the Soviet Union and emergence of these Central Asian nations as independent countries, a well-organized effort was launched from abroad, particularly from Saudi Arabia and some Gulf Sunni countries, to spread Wahhabism, a heretical deviation from Islam, in its most virulent form, throughout Central Asia. Fighters were trained, arms were provided, and an organization of some sort was set up to undermine the newly independent and politically weak nations. That not only posed an existential threat to the Central Asian countries, but rang alarm bells in Moscow and Beijing. Since the appearance of the Saudi-funded jihadis, supported by London and Washington, violence has been used to weaken the political developmental process, bring economic growth to a halt, and even threaten the very ingredients necessary for future economic growth.

In this context, China’s OBOR provides hope of strong future development because its mutually beneficial features have begun to emerge. China’s investments in infrastructure and in developing cadre of skilled manpower in these countries go hand-in-glove with the Russian efforts to provide on-the-ground security using its vast security apparatus and with the work of the SCO. The success of Russia’s efforts is of equal importance to that of the OBOR. Russia, situated north of these Central Asian countries and bordering Kazakhstan, is fully cognizant of these countries’ topography and demography, and is an important trade partner.

China’s Natural Gas and Other Investments

China’s OBOR-related investments in Uzbekistan span a range of sectors. One prominent field of investment is in developing Uzbekistan’s natural gas reserves and gas transportation infrastructure. This features the Central Asia-China gas pipeline, of which Uzbekistan is the linchpin: All three lines run through Uzbek territory, as will the fourth (Line D), currently under construction. The three existing lines, A, B, and C, already supply 55 billion cubic meters of natural gas a year to China. This constitutes 20 percent of China’s annual natural gas consumption. These lines, already the largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) network in Central Asia, will supply another 30 billion cubic meters annually when Line D is completed, further increasing China’s dependence on trans-Uzbek pipelines.

In addition, Chinese investments in the economy of Uzbekistan exceed $6.5 billion. More than 600 enterprises in Uzbekistan operate with Chinese capital. Significant joint projects have been implemented, including in the Jizzakh and Angren economic and industrial zones.[4]

Uzbekistan on the New Silk Road

China’s OBOR has identified the importance of building a railroad linking Kashgar (Kashi), in its Xinjiang province, to Uzbekistan by way of Kyrgyzstan, which lies between them. It would form a southern spur from the rail line that travels across Xinjiang to Kazakhstan, and would run from Kashgar in Xinjiang through the Arpa valley via Kyrgyzstan’s Kara-Suu town, and on to the Uzbekistan city of Andijan in the Ferghana Valley. At present, there is no direct rail link between China and Uzbekistan through Kyrgyzstan, which “considerably complicates the freight transport between the two countries,” according to Sofia Pale of the Russian Academy of Sciences.[5]

Pale explains the importance of the direct link:

View full size

uzbekistan.de

The Qamchiq Tunnel in the Angren-Pap railroad in Uzbekistan. |

In addition to the export of Chinese goods to local markets, China has plans to use the Kyrgyz rail links to import hydrocarbons from Uzbekistan and earth metals, iron, copper, and aluminum ores, coal and uranium from Kyrgyzstan. Given China’s desire to reach the largest possible area in order to increase its turnover, it is not surprising that the idea of building a railway linking China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan will soon be put into action by the Chinese. The project is to connect China not only with Uzbekistan via Kyrgyzstan, but also with Tajikistan, and then rail track will be laid through Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey, until finally, they can be connected to the European railway network. Incidentally, China has chosen the European standard gauge for this task, not Russian.

The “earth metals” referred to here are usually called the “rare earth metals,” which include scandium, yttrium, and the 15 lanthanide elements on the Mendeleev Periodic Table.

Political Roadblocks

Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev showed a great deal of enthusiasm for the railroad in 2012, and in early 2015, after prolonged talks, a route linking China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan was agreed. China is to build the 500 kilometer segment in Kyrgyzstan, investing $6 billion. Kyrgyzstan hopes to gain about $200 million per year from the transit of goods through its territory. On the Uzbekistan side, Uzbekistan said in September 2016 that it had finished 104 kilometers of the 129 kilometer Uzbek stretch of the railway.

Kyrgyzstan, however, is not of one mind about the project. The President himself has vacillated. Pale reports,

Many Kyrgyz officials have questioned the feasibility of the construction itself, because all work will be carried out exclusively by Chinese companies, and the railway will only start to make money for Kyrgyzstan after China’s expenses have been paid off. Moreover, according to the expert on infrastructure projects in Central Eurasia, Kubat Rakhimov, the profitability of the project for Kyrgyzstan is in doubt. He believes that China is unlikely to allow someone to make money on transit. In addition, the mountainous landscape of Kyrgyzstan significantly scales up the risk of increases in construction costs.

These considerations of feasibility and profitability are “practical” arguments that seem to disregard the promise, for all partners, of the greater OBOR conception. But the real source of resistance may lie in the realm of politics and geopolitics. There are concerns that the railroad may result in “the strengthening of Uzbekistan’s dominance in the region and even the probability of violation of Kyrgyzstan’s territorial integrity,” according to Pale. And within Kyrgyzstan,

There are unspoken contradictions between representatives of the ruling elites of the northern and southern regions of the country, and the construction of the railway could shift the balance of power in the direction of one of the competing camps.

Pale is referring to the two elites, a northern (ethnic Kyrgyz) and a southern (ethnic Uzbek). The project will run through the south of Kyrgyzstan, causing the northern elite to fear that a shift in the internal power balance may result. She also refers to the fear that a strengthened southern region could attempt to secede and that it could be encouraged to do so by Uzbekistan.

Many Kyrgyz propose that a north-south railway—Russia-Kazakhstan-Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan—uniting the two parts of the country, must be built first; they argue that if the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railroad is built first, the north-south line may never be built.

These political considerations are also intertwined with geopolitical tensions—tensions between Russia and China with respect to Central Asia, and tensions aggravated by Anglo-American manipulations in the Tulip Revolution of 2005.

Kyrgyzstan will have to resolve these internal conflicts, and it is likely that China—if not also Uzbekistan, in particular—needs to take a hand in overcoming Kyrgyzstan’s fears. Kyrgyzstan’s situation is compounded by its weak financial condition, including heavy indebtedness. It has virtually no capital to invest.

Rail Line: Tashkent to Fergana Valley

View full size

uzrailway.uz

One of the 6 viaducts and 25 bridges on Uzbekistan’s new Angren-Pap railway line. |

Meanwhile, China and Uzbekistan have together developed a very important rail link between Tashkent and the Ferghana Valley. This is the Angren-Pap railway, inaugurated on June 22, 2016 by President Xi Jinping and the late Uzbek President Islam Karimov.

The highlight of this rail link is the 19.2 kilometer Qamchiq Tunnel, the longest in the 1,520 mm rail-gauge region and the key element of the project. The inaugural train from Angren to Pap (Pop)—a Chinese-built O’zbekiston electric locomotive and four coaches—passed through the tunnel in 16 minutes, according to news reports. The tunnel eliminates the need for Uzbek trains to transit Tajikistan to reach the Ferghana Valley, and provides an all-weather alternative to the road over a pass at an altitude of 2,267 meters. The rail line, built by China Railway Tunnel Group, also includes 25 bridges and 6 viaducts with a total length of 2.1 km, and four stations at Orzu, Kul, Temiryulobod, and Kushminor.

Industrial Investments

The Angren-Pap railroad is destined to play an important role in Uzbekistan’s industrial progress in the coming years. It will become a very important cog in the Angren Special Industrial Zone (SIZ) that includes 16 investment projects worth more than $224.8 million to be implemented in the coming years.

Located at the intersection of Uzbekistan’s various transport routes close to Tashkent region, Angren SIZ has received $60 million from the Uzbek government. Over the past years, leading companies in Austria, Bulgaria, Great Britain, India, Singapore, and South Korea have partnered in commissioning enterprises specializing in the production of copper pipes of different diameters, industrial silicon, energy-saving LED lamps, coal briquettes, construction and finishing materials, and sugar. The joint enterprises have provided more than a thousand new jobs. The Uzbek-Chinese enterprise Jun Long Industrial in Angren SIZ has established the manufacture of coal briquettes from coal powder. A joint Uzbek-South Korean venture, Uz-Shindong Silicon, has been recently commissioned to produce industrial silicon. The projected cost of the plant is $8.67 million, providing about 200 new jobs. The Uzbek-South Korean company Egl-Nur is another successful example. Driven by modern technologies, the enterprise manufactures world-standard, energy-saving LED lamps.

In addition to Angren SIZ, Uzbekistan has two other long-established Free Industrial and Economic Zones, Navoi and Jizzhakh. The zone in the Navoi region (west of Tashkent and close to Bukhara) was established in 2008, and the Jizzakh zone (in the central part of the country, close to Samarkand) with its branch in Syrdarya district, was founded in 2013.

Several Chinese companies—Nan Yang Mulanhu, Henan Sine, Pinmian Co. Ltd, and Hebey An Feng Da Group—have shown interest in implementing textile-producing enterprises in the Jizzakh industrial and economic zone. Uzbekistan is the 6th largest producer of cotton in the world and cotton is its main cash crop.

According to a company representative, the total planned design capacity of the enterprises will amount to annual production of 30 million square meters of cotton fabric, 13,000 tons of knitted fabric, and 15 million garments including knitwear. Up to 80 percent of the products will be exported in accordance with the terms for creating the enterprises.

OBOR Draws in Japan and Russia

View full size

wikipedia |

These linkages with China, developed from the Chinese initiative in the form of the OBOR, have attracted other international companies. For instance, the Japanese behemoths, Mitsubishi Corporation and Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd, in October won a turnkey contract to construct the Turakurgan thermal power plant in the Namangan region of the Ferghana Valley in 2017. It will have two units, each generating 450 MW, with steam and gas turbines.

Similarly, Russia’s oil company, Lukoil, announced in November an investment of $500 million for the development of the Gissar gas and gas condensate fields in the Kashkadarya Region of Uzbekistan (situated in the basin of the Kashkadarya (river) on the western slopes of the Pamir Alay Mountains, bordered by Turkmenistan and Tajikistan).

The Cultural Dimension

One of the most important contributions of the OBOR is the exchange of cultural traditions among the countries that are becoming interlinked through railroads. In some cases, as in the case of Uzbekistan and China, the task involves reviving the long-lost cultural exchanges that took place when the Silk Road and other trade routes were alive in the past.

In the 20th century, Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, served throughout the Soviet period as a center for Chinese studies. Beginning in 1957, people from all over Central Asia came to Tashkent to learn Mandarin. Since becoming independent in 1991, Uzbekistan has received support from the Chinese government to continue teaching Mandarin. The Confucius Institute in Tashkent, which opened in 2005, is not only the first Confucius Institute in Uzbekistan, but also the first in Central Asia. Like other Confucius Institutes around the world, its mission is to promote the teaching of Mandarin and develop cultural and educational exchanges between China and the host country. Now the study of Chinese is viewed in Uzbekistan as advantageous for business and for professional employment abroad, and many students hope to get stipends to study in China.[6]

Footnotes

[1]. Qu Hongbin, “China Ramps Up Its Silk Road Initiative,” Supply Chain 24/7, Dec. 22, 2016. http://www.supplychain247.com/article/china_ramps_up_its_silk_road_initiative

[2]. S. Frederick Starr, Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane (Princeton University Press: 2013), p. 43.

[3]. Rafis Abazov, The Palgrave Concise Historical Atlas of Central Asia (New York: Palgrave Macmillan: 2008).

[4]. Mirzokhid Rakhimov, “Dynamics of Uzbek-Chinese Relations,” China.org.cn, June 21, 2016. http://www.china.org.cn/opinion/2016-06/21/content_38708678.htm

[5]. Sofia Pale, “Kyrgyzstan and the Chinese ‘New Silk Road’,” New Eastern Outlook, Sept. 3, 2015. http://journal-neo.org/2015/09/03/kyrgyzstan-and-the-chinese-new-silk-road/ However, the Kyrgyz trading town of Kara-Suu, located close to the Uzbek border, serves as a vital link to Uzbekistan: It is situated on the interregional highway that links the Kyrgyz capital of Bishkek, Osh, and the capital of China’s Xinjiang province, Urumqi. There is also a railroad that links the administrative and economic center Jalal-Abad in southwestern Kyrgyzstan to the Uzbek town of Andijan and runs through Kara-Suu, but it is not connected to the rail line to Urumqi.

[6]. Julie Yu-Wen Chen and Olaf Günther, “China’s Influence in Uzbekistan: Model Neighbor or Indifferent Partner?” Jamestown Foundation, China Brief 16:17 (November 11, 2016). https://jamestown.org/program/chinas-influence-uzbekistan-model-neighbor-indifferent-partner/