The Southeast Asia Water and Power Alliance:

A Laotian Plan Inspired by NAWAPA

by Mohd Peter Davis

May 2012

This article appears in the May 11, 2012 issue of Executive Intelligence Review and is reprinted with permissionHe was only 11 years old in 1980 when he left his village in Laos and bravely swam across the mighty Mekong River at Vientiane with his older brother, surviving the strong current and landing in Thailand as one of the youngest self-propelled refugees from Laos. They were quickly rounded up on the opposite bank by the waiting Thai police and kept in a grossly overcrowded prison, joining others, some of whom had been locked up for more than two years.

Thone Siharath, who left his home as a child, during the “Secret War” against Laos in the 1960s, is now working to create a Southeast Asia Water and Power Alliance, based on NAWAPA. |

“Why did you risk your life in such a dangerous swim, just to get jailed?” we asked Thone Siharath, now home again in Laos, after 32 years in Belgium, France, Denmark, and London.

“I wanted to get an education, and there was no other way. Many things had been bombed and my parents saw no future for us in Laos,” Thone explained. “Perhaps because I was so young, I was selected as a refugee, and within four months I was flown to Belgium where I did my schooling.”

Thone started work straight from school, and educated himself whilst employed in an international chain of Thai restaurants and workshops, by moving around Europe, the Mideast, and Thailand. He worked his way up to become a shareholding director, based more in the London head office and master franchise branch of the restaurant. Thone moved around, specialising in computer-managing the whole chain of restaurants, especially the financial reports, food and menu engineering, including raw food and material purchasing, monthly consumption of resources, health standards, all the way to a traceability system demanded by the authorities as his companies catered for international airlines and supplied supermarkets and many others.

Vientiane, Laos 2012

Thone had just picked me up, together with my close colleague Mazlin Ghazali, a practicing Malaysian architect, from the Laos international airport, only ten minutes from the Vientiane city centre. Thone had contacted the LaRouche Movement a few months previously, expressing keen interest in the NAWAPA (North American Water and Power Alliance) program and putting forward a bold plan for a similar SEAWAPA project (Southeast Asian Water and Power Alliance) based on the abundance of freshwater in Laos. We were just as keen to collaborate from nearby Malaysia.

On the banks of the Mekong, we were gazing across the same stretch of the Mekong River that Thone remembers so well from his boyhood, and began to piece together the history that had forced so many to leave Laos. The departure of the French colonisers in 1954 took many Laotians with them, but it was the Indochina War, and especially the massive saturation bombing of the Plains of Jars in Northern Laos, that led to a mass exodus.

From 1963 to 1973, 2 million cluster bombs were dropped by B52s on Laos, with a population of only 3 million, 85% of them rural subsistence farmers. Laos has been characterised as the most heavily bombed country in the history of the world. It was an unsuccessful attempt to destroy the ingenious Ho Chi Minh Trail from North Vietnam that supplied the lifeline to the insurgency in the South during the “brains versus brawn” asymmetric war against the vast technological superiority of the American military. For Laos, the war was not over when the Americans were defeated. The 2 million “boomies”—small antipersonnel bombs—left over from the bombing raids continued to kill and maim, mainly children, for 25 years after the war.

The reason for the senseless and useless American war in Indochina has left most in bewilderment, including the American military veterans. The long war did however serve a vitally necessary function for the survival of the British Empire. The war was highly successful in sabotaging the American optimism for grand development programs and space exploration that President John F. Kennedy was pursuing, in the tradition of the late President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The British-orchestrated assassination of President Kennedy, who refused to engage U.S. combat troops in the war in Indochina, opened the door for the genocidal war, whose real target was not Vietnam, nor Laos, nor Cambodia—which were no threat at all to the British Empire—but America’s economic power and can-do legacy, inspired by the Roosevelt Administration—an operation from which America has never recovered.

The Laotian Homecoming

Seven months ago, Thone came back permanently to Laos, along with a now rapidly increasing flow of expatriates from around the globe. We wanted to know what was driving this process.

“In my case it was quite simple. The London branch of the restaurant chain had relocated and downsized. There were not enough incomes for big earners. For years, I was closely monitoring the price of food raw materials, and it came to the point where we could no longer absorb the unrelenting price increases or pass them on to our customers.”

He explained that most of the other expatriates had similar stories—loss of good jobs, and being forced, if they were lucky, to menial low paid jobs. They preferred instead to return home with their sought-after skills and living knowledge of America, Europe, and other Western countries, to collaborate with their businessmen relatives. This growing section of the Laos community, with its skills and knowledge of advanced countries, is the most eager to develop the nation. Even though they have not lived in Laos for most of their lives, they are very patriotic. These expatriates receive no animosity on their return. They are all welcomed back home with open arms. “Especially the wealthy ones!” quips Thone.

This is because social security throughout Asia is based historically on close family ties, even among distant relatives who share even one drop of blood in common, and with those relatives overseas for long periods. The expatriates are returning home due to the economic collapse in America and Europe which can no longer allow them to earn a reasonable living. They are linking up immediately with their extended families in Laos to expand the family business interests. They want to use their skills to develop these businesses and to build the nation. There is no conflict of interest.

The LaRouche Factor

Thone, in his short time back in Laos, is interestingly different from other expatriates. Looking for something unique about Laos that the rest of Southeast Asia required, he discovered, by research through the Internet, that the seven-month monsoonal rains, the Pacific Typhoons, and the melting ice from Tibet, deposit more freshwater on Laotian territory than almost anywhere else on Earth.

However, this monumental deluge is almost completely unused, flowing back to the sea mainly via the Mekong River and its tributaries, stored/flowing out, underground or evaporated, unused. The first phase of Thone’s long-term vision is to comprehensively dam the Mekong River (Figure 1) at geographically suitable points, and make it navigable all year ’round from the sea. This will permit the capture of vast amounts of additional water feeding into the Mekong, including from Laotian tributary dams, and especially the untapped reserves of underground water located higher up the river basin.

|

FIGURE 1  |

The fresh drinking water and hydroelectricity surplus to Laos’s modest needs can be distributed to other countries in Southeast Asia and to southern China, and even the dry Middle East, plus Afghanistan, using oil pipeline technology. Excess water to all these requirements can be stored in existing lower underground reservoirs in Laos.

In his research on global water, Thone, not surprisingly, came across the extensive work done by Lyndon LaRouche’s Executive Intelligence Review (EIR) over the past decades on the development of the Mekong River basin, and from there, he quickly discovered the NAWAPA proposals on the LaRouche Political Action Committee website (LPAC, www.larouchepac.com). NAWAPA will be the largest infrastructure project in history, and the mobilization spearheaded by LaRouche’s organization is exciting people and governments around the world.

Thone immediately made contact with the LaRouche Movement. He got a fast and serious response, and did his own crash course of the LPAC website, as well as 21st Century Science & Technology and the weekly EIR. I was forwarded his e-mails for comments from Malaysia. I was concerned that expatriates, even though patriotic, might get seduced by the money, especially as their businesses become more successful. They easily see the immediate commercial opportunities in national projects, but not the big picture required for nation-building. I was concerned about this problem before our trip to Laos.

However, in our e-mail exchange I was pleased to receive Thone’s response to the LaRouche Movement: “You and all the LaRouchePAC Team are giving hope to humanity.” It was similar to my own experience ten years ago on discovering the LaRouche Movement whilst trying to understand what Western power was behind the sheer evil of 9/11. As I have since learnt, it is always the British. More precisely, the British Empire has the virtual monopoly on evil, and blatantly promotes its intention to exterminate 6 of the 7-plus billion people on Earth, or 85% of humanity, by starvation, disease, or even thermonuclear war, if need be. Fortunately, the Empire is now completely bankrupt and can be overthrown, having almost no real wealth left to run its nasty operations!

A National Plan for Laos

Thone’s first-phase idea, to dam the Mekong River and tributaries at appropriate sites in Laos, is inspired by NAWAPA. What makes it particularly feasible, is the geography of landlocked Laos, which is separated on its eastern border with Vietnam by a 1,000-km-long mountain range, the Annanitese Cordillera. The Mekong River runs alongside this natural barrier and has carved out deep channels which can be easily dammed. After generating hydroelectricity, the water and electricity can be piped to other countries. To do this, Laos needs the technical advice of the American water engineers guiding the NAWAPA project, for the best location and specifications of the dams.

The best long-term solution for funding is seen as a form of America’s Credit System under Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt, as proposed today by LaRouche. At the moment, funding for the dams, it is hoped, can come from Chinese and Japanese grants. China seems willing, as it is also willing to build a railway from China through Laos, to connect to the main railways in Thailand and Malaysia and Singapore, although problems with details of the rail plan have stalled the project for now.

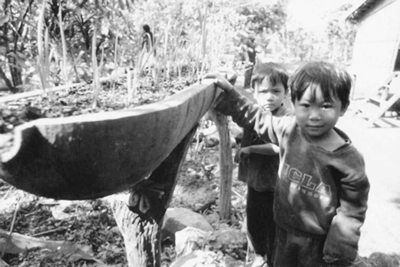

Lao children stand next to a vegetable pot made from a bomb casing of disarmed unexploded ordnance. |

Japan has pledged USD7.4 billion to the Mekong countries for trunk roads, which is seen as promising. Thone thinks that Laos, with modern infrastructure will be very appealing to Japan and the Rim of Fire countries that are being ravaged by earthquakes, tsunamis, typhoons, and tornadoes. The Annanitese Mountain Range protects Laos from the damage of these natural disasters, and can be a safe haven for modern factories, such as auto and electronics plants.

We came to Laos to share our Malaysian inventions, Deep Tropical animal production for mass-producing food [see interview in Economist], and Honeycomb housing to accommodate every family in modern housing. Our point was that water and electricity exports alone would not generate sufficient wealth to develop Laos. Modern animal production based on our grass plantations, and climate housing for superior domestic animal breeds, could become a high-value, world-class export industry of lamb, beef, milk, and cheese, and transform poor farmers into wealthy modern farmers.

Similarly, Malaysia’s innovative Honeycomb housing could rapidly house the whole population, now 7 million, in new towns and cities, generating large numbers of construction jobs and building materials factories. Indeed, this concentration on fairly simple indigenous food and housing industries is a model for all developing countries. If Laos can also attract high-tech Japanese and Korean factories, the combination can rescue the nation trapped in the 16th Century and propel it into the 21st Century.

Progress Report

In an e-mail sent to us back in Malaysia, after our 48-hour trip to Laos in late April 2012, Thone accurately summed up our joint progress:

“Dear Mohd and Mazlin, I would like to thank you and the LaRouche Team, on behalf of the Lao Chamber of Commerce & Industry, and Ministry of Education, and SEAWAPA, for the excellent opportunity for us to meet both of you and for sharing with us your good works on Biospheric Engineering. We were much impressed with your whole experiences, and it was a pleasure to share ideas with you. My team and I gained a lot of knowledge from all of you and thank you also for the signed books. We hope that you were satisfied with the efforts of our side. It is a pleasure for me to say that we would be more than happy to work with you for pilot projects, first in sheep farming followed by housing projects. We will discuss with the Ministry of Education for further development.

“As you had witnessed, we are writing a letter of intent to advise the Ministry of Water Management and Environment to prepare the SEAWAPA Master plan for the whole of Laos with the intent to create the biggest scale of Laos topography possible and study the effect of weather, water behaviour, time, heat, earth movement and other factors. We intend to present our project to get the grants from Japan and from China, since SEAWAPA will create a huge surplus of food and power that these two countries and others urgently need to stabilise speculated prices and avoid immediate hyper-inflation.

“—Thone Siharath”

Our Laos visit demonstrated that Development is enjoyable and a natural characteristic of the human species. Without the British Empire sabotaging our every move just to cling onto power, imagine how easy and rewarding it will be to rebuild the world with science and technology, a world fit for humanity.

Mohd Peter Davis is a retired Visiting Scientist at the Universiti Putra Malaysia.