Henry A. Wallace and the Art of Feeding Mankind

By Karel Vereycken

December 2017

Edited version of a presentation to the General Assembly of Solidarité & Progres in Paris, June 2008.

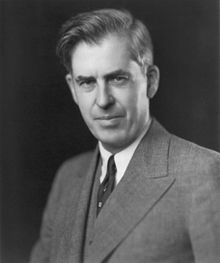

In a powerful speech entitled “The Price of Free World Victory” delivered to the Free World Association in New York City on May 8, 1942, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Vice President Henry Agard Wallace laid out his vision to bring mankind into the “Century of the Common Man.”

It stood as a sharp polemic against the anglophile pro-Morgan interests, of such folk as Time magazine’s Henry Luce, which had called earlier in 1941 on America to follow the model of the 19th Century’s “British Century,” and rename it the “American Century.”

America, argued Wallace, after having being freed from slavery by President Abraham Lincoln in the 19th Century, and after freeing the world of the slavery of the Nazi system at that time, had to commit itself, once the war terminated, to also free the common man from the slavery of daily want—the slavery of hunger, sickness, and social insecurity.

Wallace’s words were based on his own experience. As FDR’s Secretary of Agriculture, he had played a key role in the “New Deal” that brought the United States out of an otherwise hopeless depression, which included feeding its own people.

“Modern science,” said Wallace in his 1942 speech, “which is a by-product and an essential part of the people’s revolution, has made it technologically possible to see that all of the people of the world get enough to eat. Half in fun and half seriously, I said the other day to Madame Litvinov: ‘The object of this war is to make sure that everybody in the world has the privilege of drinking a quart of milk a day.’ She replied: ‘Yes, even half a pint.’ The peace must mean a better standard of living for the common man, not merely in the United States and England, but also in India, Russia, China, and Latin America—not merely in the United Nations, but also in Germany and Italy and Japan.

“Some have spoken of the ‘American Century’: I say that the century on which we are entering—the century which will come out of this war—can be and must be the century of the common man. Everywhere the common man must learn to build his own industries with his own hands in a practical fashion. Everywhere the common man must learn to increase his productivity so that he and his children can eventually pay to the world community all that they have received. No nation will have the God-given right to exploit other nations. Older nations will have the privilege to help younger nations get started on the path to industrialization, but there must be neither military nor economic imperialism. The methods of the 19th Century will not work in the people’s century which is now about to begin. India, China, and Latin America have a tremendous stake in the people’s century. As their masses learn to read and write, and as they become productive mechanics, their standard of living will double and treble. Modern science, when devoted wholeheartedly to the general welfare, has in it potentialities of which we do not yet dream.”

Today, that great vision remains largely unfinished. At the beginning of the 21st Century, out of the roughly 1.43 billion farmers of this planet, the majority of them women, only 27 million (less than 2%!) have tractors, fewer than 300 million use animal labor, and close to 1 billion are enslaved to the limited resources of their own muscles. As a result, some 530 million very poor farmers compose the core of those 900 million of the world population struck with chronic hunger.

The solution for this problem is perfectly known. As we will document here, Wallace’s agricultural policies and scientific optimism define a coherent concept of the art of feeding mankind, a concept that has proven its efficiency and served as a crucial reference point for launching the “Green Revolution,” first in Mexico by Wallace himself, and then later in the early 1960s in India and Asia, and later in Africa. The same concept was also one of the sources of inspiration for De Gaulle’s and Adenauer’s 1962 Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), a policy aimed to ensure permanent peace and security through food security.

Henry Agard Wallace

Henry A. Wallace was born in Iowa on October 7, 1888. His father, Henry Cantwell Wallace, was the editor of a farm paper called Wallaces’ Farmer and served as Secretary of Agriculture in the Administrations of Presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge from 1921 until his death in 1924.

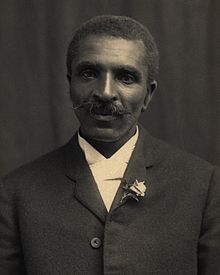

George Washington Carver, the first black teacher that Iowa State ever hired, used to take long walks into the surrounding fields to study plants for research. On some of these walks he took a little boy with him, the 6-year-old son of a friend and dairy science professor. Carver shared his love of plants, and the boy responded enthusiastically. At the age of 11, that boy began performing experiments with various varieties of corn. His name was Henry A. Wallace, who would study plant genetics and cross-breeding in the same university under Carver.

Already then, the young Henry Wallace discovered a successful strain of corn that produced a greater yield while resisting disease better than normal corn. As an adult, Wallace’s fascination with corn continued. He developed some of the first hybrid corn varieties and even published his findings in his father’s paper, Wallaces’ Farmer Magazine. He also founded Pioneer Hi-Bred International, Inc.

Planting his hybrid seeds, the per acre yields of Midwestern corn doubled and even tripled. This triumph allowed the young Wallace to found his own business to manufacture and distribute the plants, a venture that gave him valuable experience for his later career in public service.

The Wallaces had traditionally been a Republican family, but the shock of the Great Depression and its impact on rural America brought Henry to shift political affiliations. Disgruntled by the Coolidge and Hoover agricultural policies, Wallace threw his support to the Democrats. In 1932, Wallace supported Franklin Roosevelt, who in turn selected Wallace as his Secretary of Agriculture.

Secretary of Agriculture

A firm supporter of government economic intervention, Wallace vigorously implemented the “controversial measures” of the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), enacted on May 12, 1933. For the first time, Congress declared that it was “the policy of Congress” to balance supply and demand for farm commodities so that prices would support a decent purchasing power for farmers.

After some study, economists for the U.S. Government decided that during the time from 1909 to 1914, the prices that farmers got for their crops and livestock were roughly in balance with the prices they had to pay for goods and services they used in the production of crops and livestock and family living. In other words, a farmer’s earning power was on a par with his or her purchasing power. This concept, incorporated in the AAA, was known as “parity.”

Never before in peacetime had the Federal Government sought to regulate production in American farming, with government planning designed to battle the main problem of that period in U.S. farming—overproduction and low prices.

Although the stock market crash of October 1929 represents, for many, the onset of the Great Depression, the decade of the 1920s was one of depression for much of agricultural America.

World War I had severely disrupted agriculture in Europe. That turned to the advantage of farmers in the United States, who increased production dramatically and were therefore able to export surplus food to European countries. But by the 1920s, European agriculture had recovered and American farmers found it more difficult to find export markets for their products. Production had flourished under the high prices generated by World War I. Wartime demand ended suddenly with the Armistice in 1918. The 1920s saw overproduction and declining prices. Farmers continued to produce more food than could be consumed, and prices began to fall. The loss of income meant that many farmers had difficulty paying the mortgages on their farms. Farm mortgage debt rose from $3.2 billion in 1910 to $9.6 billion by 1930 and brought many American farmers into serious financial difficulty. However, with the Great Depression gripping cities as well as rural areas, there were few alternatives.

Overproduction resulting from shrinking domestic and foreign markets and the sharp drop of purchasing power collapsed prices dramatically. In South Dakota, for example, the county grain elevators listed corn as minus three cents a bushel—if a farmer wanted to sell them a bushel of corn, he had to bring in three cents. Fields of cotton lay unpicked, because it could not be sold even for the price of picking. Orchards of olive trees hung full of rotting fruit. Oranges were being sold at less than the cost of production. Grain was being burned instead of coal because it was cheaper.

The AAA

Such drastic times required drastic measures, and as soon as FDR was elected, Secretary Wallace gave responsibility for drafting legislation to Mordecai Ezekiel, a senior Agriculture Department economist, and Frederic P. Lee, a Washington lawyer employed by the American Farm Bureau Federation. Roosevelt sent the draft to Congress on March 16, stating: “I tell you frankly that it is a new and untrod path, but ... an unprecedented condition calls for the trial of a new means to rescue agriculture.”

Congress passed the far-reaching legislation, and it was signed on May 12, 1933, as the AAA. This Act authorized production adjustment programs that were a direct outgrowth of the experience of the Federal Farm Board. It authorized the use of marketing agreements and licenses, which had been used already by producers to promote orderly marketing of perishable fruits and vegetables. Also, under authority of the AAA large quantities of surplus food were distributed via Food Stamps to needy households through and to school lunch programs.

The day after the AAA was adopted, on May 13, 1933, in a radio speech labeled “A Declaration of Interdependence,” Wallace, combining determination and great compassion, told farmers over the radio:

“In the end, we envision programs of planned land use; and we must turn our thought to this end immediately; for many thousands of refugees from urban pinch and hunger are turning, with little or no guidance, to the land. A tragic number of city families are reoccupying abandoned farms, farms on which born farmers, skilled, patient, and accustomed to doing with very little, were unable to make a go of it. In consequence of this back-flow there are now 32 million people on the farms of the United States, the greatest number ever recorded in our history. Some of those who have returned to farming will find their place there, but most of them, I fear, will not.”

He added: “The adjustment we seek calls first of all for a mental adjustment, a willing, reversal, of driving, pioneer opportunism and ungoverned laissez-faire. The ungoverned push of rugged individualism perhaps had an economic justification in the days when we had all the West to surge upon and conquer; but this country has filled up now, and grown up. There are no more Indians to fight. No more land worth taking may be had for the grabbing. We must experience a change of mind and heart.”

Hence, the first goal set with the AAA was to reduce the amount of crops that farmers produced and the number of livestock sent to slaughter. Less crops and fewer animals would mean that prices for agricultural products would rise, increasing farmers’ abilities to pay off debts and enhancing their purchasing power. To convince farmers to reduce production, the AAA authorized the Federal Government to pay subsidies to farmers for growing smaller crops and raising fewer animals.

In an earlier speech, “The Farm Crisis,” delivered by radio on March 10, 1933, Wallace keenly had observed that “During the few years just preceding 1929, we were selling in foreign markets the product of roughly 60 million acres of land. The value of those exports this past fiscal year was 60% below that of 1929. We must reopen those markets, restore domestic markets, and bring about rising prices generally; or we must provide an orderly retreat for the surplus acreage, or both.”

In “The Cotton Plow-Up,” a speech delivered on radio on August 21, 1933, Wallace defended his policy: “On one of the largest cotton plantations in Mississippi I saw a dramatic instance of America’s present effort to catch its balance in a changed world. There were two immense fields of cotton with a road between them. On one side of the road men with mules and tractors were turning back into the earth hundreds of acres of thrifty cotton plants nearly three feet high. On the other side of the road an airplane was whipping back and forth at 90 miles an hour over the same kind of cotton and spreading a poison dust to preserve it from destruction by the boll weevil. Both of these operations were proceeding side by side on the same farm, and both in our present critical state of economic unbalance were justifiable and necessary.”

To tackle that problem, Wallace offered hog and cotton farmers a single opportunity to improve their stagnating markets by plowing under 10 million acres of cotton and slaughtering 6 million pigs and 220,000 pregnant sows. For the losses, the government would issue relief checks totaling millions of dollars. Wallace scorned those who ridiculed his plans without considering the logic behind them, observing, “Perhaps they think that farmers should run a sort of old-folks home for hogs.”

After these dramatic short-term measures to curb overproduction and provoke a rapid price increase, the AAA controlled the supply of seven “basic crops”—corn, wheat, cotton, rice, peanuts, tobacco, and milk—by offering payments to farmers in return for taking some of their land out of farming and not planting a crop.

Although it earned Wallace the nickname “The Greatest Butcher in Christendom,” the program essentially worked, and the market experienced a 50% rise in prices.

Meanwhile, FDR’s New Deal banking reforms and industrial renaissance increased the population’s overall purchasing power and former agricultural workers found productive jobs in industry and great infrastructure construction programs. Dams and rural electrification gave farmers the means to modernize production and access to fertilizer and irrigation.

Today’s Problem

Today, we are obviously not at all in the same situation as FDR was in 1933, but the same principles are at stake. Over the past two decades, globalized free trade and partisan deregulation, combined with reductions of subsidies and inventories, have driven world food prices down while reducing many nations’ population’s living standard and buying power.

Already in itself, the “world food price” is by itself a fraud. For example, if today’s world cereals production is close to 2 billion tons, only 200 million tons (10%) are traded on the world market, while that “world price” becomes the price of reference for the remaining 90%. And of those 200 million tons, 80% are traded by only three giant agro-cartels—Cargill (U.S.), Archer Daniel Midland (U.S.), and Louis Dreyfus (France).

Correctly identified in the early 1920s and 1930s by Wallace’s advisor Mordecai Ezekiel as the “inelasticity” of the food and agriculture market, a small discontinuity (e.g., drought, catastrophe) in the supply or demand of food and agricultural products, if unregulated, is sufficient to provoke major price instabilities.

Hence feeding the planet is a time needing process. While financial speculation prospers by “surfing” on rapid shifts of commodity prices, food security, as a policy, is uniquely based on stability, because a price too low prevents farmers from planning and investing in tomorrow’s production, while a price too high destroys the population’s access to food, both in quantity and quality.

The success of FDR’s New Deal and Wallace’s AAA established a valid and proven model that was as far distant from Soviet-style totalitarian regulation as it was from British free trade looting and, as such, became a model for the post-war reconstruction period.

It only required for something that the Anglo-Dutch financier cartels hate the most: governments that govern, rather than being mere tools of some kind of special interests.