Highlights | Calendar | Music | Books | Concerts | Links | Education | Health

What's New | LaRouche | Spanish Pages | Poetry | Maps

Dialogue of Cultures

SARS Rings the Alarm Bell: Restore Public Health System

Congress Hears Public Health

Not Up to Epidemics Like SARS

by Linda Everett, from the May 16, 2003 Executive Intelligence Review

Related Articles

In the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, every sane policymaker, in a plethora of Congressional hearings, rallied for rebuilding the nation's public health infrastructure to deal with possible bioterrorist threats. Now, 18 months later, after the anthrax attacks, the coast-to-coast spread of West Nile virus, the re-emergence of both malaria and tuberculosis, the faltering smallpox vaccination drive, and the eruption of the global epidemic of SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), there is new scrutiny of our "tattered" public health system. Despite some Federal bioterrorism preparedness funding to states, it is facing a withering decline.

Since its probable start in a southern province of China in November, SARS has sickened over 7,000 people in 27 countries, killing 500. U.S. health officials report 320 cases of probable and confirmed SARS in this country.

The war against this, or any infectious disease epidemic, cannot be won as long as the economic austerity policies fuelling many nations' overall fiscal disintegration are allowed to continue, thereby cannibalizing critical infrastructure. As Democratic Presidential pre-candidate Lyndon LaRouche said just weeks after Sept. 11, 2001, we require a military-style command authority to build up medical and infrastructural defenses, including what modern society has come to know as public sanitation, including adequate ratios of clean water, power, and transportation per household. Undertaking this mandate cannot be put off.

System 'In Tatters'

On April 29, Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.) warned the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee that the U.S. public health infrastructure has been cut to the bone, leaving no excess capacity to deal with SARS. Citing a survey of health departments undertaken by his office, Senator Kennedy reported a devastating picture:

- New Orleans Public Health Department Director Kevin Stevens said, "We have very few resources, and should we have a SARS outbreak, we are very poorly prepared."

- The Los Angeles Department of Health and Services (California) said that they have about 2,000 people die every month from unexplained pneumonia. They reported: "We have dealt with SARS to the detriment of other diseases."

- Philadelphia has no city-owned hospital; the health department has no funds to set up a quarantine facility of its own. It would have to rely on hard-pressed independent hospitals to house SARS patients in isolation.

- Seattle has only limited facilities to isolate contagious patients. That city is already facing the highest number of tuberculosis cases it has seen in 30 years. They have only two full-time infectious disease physicians.

Dr. Julie Gerberding, Director of the Atlanta-based U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reported to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce on May 7, "Sadly, our public health system was allowed to deteriorate for decades—it is in tatters." The dispersal of $1 billion in Federal bioterrorism preparedness funds has helped in some areas, but enormous public health infrastructure needs still exist. Dr. Gerberding specifically cited the need for more preparedness planning, and better epidemiological capacity to investigate and to respond quickly to disease or other incidents. "We have a tragedy in our public health workforce," Dr. Gerberding said. "We need trained professionals everywhere."

She also called for more laboratory capacity, since a lot of public health labs are in "dire straits." A January study by the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL) found three-quarters of the nation's state labs are unable safely to accept samples suspected of containing multiple hazards, such as toxic chemicals and infectious organisms. Only eight states have a chemical terrorism response plan in place. Most labs are fighting just to sustain current capacity.

Another recent APHL survey on bioterrorism preparedness found that 30 states' public health laboratories faced cuts in 2003; nineteen of these had multiple programs cut. Some 33 laboratories expected cuts in 2004. One state public health department lost one-third of its staff due to budget cuts over the last decade. Amid the cuts, such states as Massachusetts need hundreds of thousands more dollars to test tissue samples for SARS. About 53% of local public health agencies say smallpox and bioterrorism planning are taking staff away from other public health services, causing reductions in influenza surveillance and cuts in other virology activities. Today, we are in the same crisis that we faced when the country was hit with the onset of West Nile and the anthrax attacks: unable to perform routine public health functions, let alone the intensified surveillance and significant extra testing needed in emergencies. The APHL reports that if states did get extra funds, needed workforces now do not exist.

Dr. Gerberding told the Senate Committee on April 29 that SARS has taught us that emerging infectious diseases are a fact of life; that the whole public health system has to be intact; and there must be continuity of public health with health-care delivery systems. "We've got to have both capacities: a viable and vibrant and robust medical care system with informed clinicians; but also, beds and surge capacity and training. That has to be immediately linked to public health research to identify what is the best way to do all this." When it comes to the public health system, Dr. Gerberding said, "We're only as good as our weakest link."

Our public health system relies on disease surveillance systems and epidemiologists to detect clusters of suspicious symptoms or disease. The latest Federal study (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2000) found just 922 epidemiologists in state and territorial agencies. Public health physicians made up only 1.3% of the public health workforce; while epidemiologists, working specifically in the core science of public health, comprise far less than 1% of it. Taken together, epidemiologists, biostatisticians, and infections control/disease investigators are just over one-half of one percent of this workforce. Some public health entities have suggested that, ideally, there would be one medical epidemiologist per 25,000 population—far below what is needed in a time of emerging infections, chronic disease, and bioterrorism threats.

|

||||

|

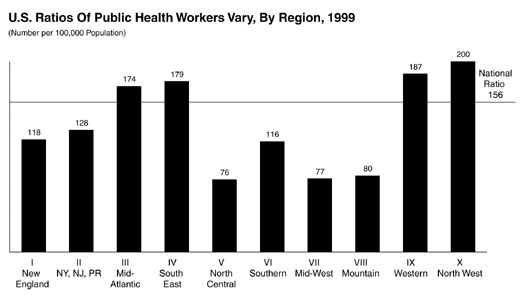

Source: The PublicHealth Workforce Enumeration 2000

Figure 1: Over the 25 years—and especially the last two years, there has been a major scale-back in the United States, in the rations of public health workers, hospital beds, staff and facilities (equipment, quarantine facilities, etc.) per population. The graph shows one aspect of this—the wide disparity in the number of public health workers (all kinds—epidemiologists, country nurses, technicians, etc.) per 100,000 people, in the ten health districts, which are set by the Department of Health and Human Services. |

||||

In the early 1970s, there was one public health worker for every 457 persons; in 1999, this had fallen to one public health worker for 635 persons (see Figure 1). Nationally, there were 158 public health workers per 100,000 population in 1999. Many states fell as low as 76 workers per 100,000 (the Northwest region of Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Indiana, Ohio, and Wisconsin). For the four-state Midwest (Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri), it's 77 per 100,000.

Hospitals: 'Worst Is Yet To Come'

In testimony given before the House Committee on Government Reform on April 9, Janet Heinrich, Director of Health Care and Public Health Issues of the General Accounting Office, said that while SARS has not infected many individuals in the United States, it has raised concerns about the nation's preparedness should it, or other infections, reach pandemic proportions. In a survey of states, the GAO found gaps in disease surveillance systems and laboratory facilities, and serious workforce shortages.

In the GAO survey, many hospitals were found to lack the capacity to respond to large-scale infectious disease outbreaks. Few have adequate medical equipment, such as ventilators, adequate stores of equipment and supplies, including medications, personal protective equipment, quarantine and isolation facilities, and air handling and filtration systems. There is an ongoing shortage of intensive care beds and isolation rooms, where infectious disease patients are treated. In five states, hospitals told the GAO they had shortages in hospital medical staff, including nurses and physicians, necessary to increase response capacity in an emergency.

There Is a Solution

As the College of American Pathologists warns: Consider where the country will be next Fall. As the flu season hits, hospitals and laboratories will face the challenge of weeding out suspected SARS cases from other illnesses, including influenza. Will there be the necessary isolation rooms in place by then? Can our public health agencies handle the Summer's avalanche of West Nile illness, and the expected increase in associated deaths and paralysis? Congress and state leaders must be put on the line to defend the public welfare. Ignoring it could be devastating to the nation.

back to DC Hospital Page

top of page

|

Science of SARSThe isolation and full genetic sequence of the new coronavirus that is responsible for the current outbreak of SARS has been accomplished by Canadian and American researchers. The genetic sequence shows that this coronavirus is unlike any previously known to infect humans. It is also not like any known coronavirus that infects animals. The sequence indicates that this is not a simple case of an animal coronavirus making a "species jump" by gaining the ability to infect humans. Research experiments in Europe have shown that the coronavirus can infect primates, and produces the same pneumonia-like symptoms seen in human beings. There has been a flurry of recent hysteria in the press about the SARS virus mutating rapidly into a more deadly form. This is not supported by any of the evidence, which in fact shows that the coronavirus isolated by the Canadian team differs in only 10 base pairs out of 30,000 from the one isolated by the American team at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). In the behavior of a coronavirus, it makes mistakes by design when it replicates, leading to minor random changes in its genetic sequence. These changes may disable the virus, or may help it replicate, or may do nothing functionally to it. There has been no research published that shows that the small natural mutation rate of this virus has changed, and to do so would require viral isolates taken and compared over a long period of time. New research has shown that other modes of transmission of the SARS coronavirus may be possible. Hong Kong researchers have reported that the virus is present in stool and urine from SARS patients, and the virus may survive up to 24 hours in excrement. This raises the question of whether sewage contamination can spread SARS, which is being investigated in the case of the Amoy Gardens apartment complex in Hong Kong, where about 300 people became infected. In a study published on May 7, Hong Kong and British researchers have shown that the death rate for SARS patients in Hong Kong who are hospitalized is higher than previously reported. The study shows that patients under 60 years of age have a mortality rate of 13%, while for patients over 60, the mortality rate is 43%. However, in other parts of the world, the mortality rates for SARS patients who require hospitalization has been much lower, and in the United States, there have been no deaths.—Colin Lowry Stopping Disease: The Yellow Fever CaseThe first line of defense against disease is to try to stop its spread. This is no less so, when the enemy-disease is a "mystery variety," i.e., one whose features (transmission, incubation, etc.) are still unknown, as in the case of SARS. The way that health care officials in Vietnam have succeeded in stopping SARS so far, has been by taking decisive action to isolate victims at its first presence, and by having the staff and infrastructure present, with which to act.

It wasn't until after World War I that many of the features of yellow fever were definitively known, though the role of the mosquito had been observed early on. The sickness is caused by a virus, and there are two epidemiological patterns of the disease. One is known as urban yellow fever (man-mosquito-man cycle); the other is jungle, or forest yellow fever (monkey-mosquito-monkey cycle). New Orleans was the center of the last major yellow fever outbreak in the United States, in July 1905. The Federal Public Health and Marine Hospital Service acted promptly, with state and city officials, to set in motion epidemic operations. A campaign was organized for controlling mosquitoes, through screening, fumigating, oiling, and, salting, and for isolation of the sick. "Tent hospitals" were set up, as they had been in previous outbreaks. On Oct. 26, 1905, the epidemic was considered under control—five weeks before the first killing frost, which usually marked the end of an outbreak. Out of a population of 325,000 in New Orleans, 3,404 were stricken with yellow fever during the siege, and 452 died. What was learned from this battle, and similar experiences—especially that led by Commander Walter Reed in Panama—combined with subsequent research and the discovery, during World War II, of DDT, enabled the control of the yellow fever infection. Yet today, this kind of fight-the-disease thinking no longer governs. For example, when the West Nile fever—a mosquito-borne virus—entered New York City in 1999, there was no effective Federal mobilization to contain and defeat it. The infection is now rapidly spreading throughout North America, and is heading southward through Mexico. —Marcia Merry Baker |

|||||||||||||

| back to DC Hospital Page top of page |

|||||||||||||

schiller@schillerinstitute.org

The Schiller Institute

PO BOX 20244

Washington, DC 20041-0244

703-297-8368

Thank you for supporting the Schiller Institute. Your membership and contributions enable us to publish FIDELIO Magazine, and to sponsor concerts, conferences, and other activities which represent critical interventions into the policy making and cultural life of the nation and the world.

Contributions and memberships are not tax-deductible.

VISIT THESE OTHER PAGES:

Home | Search | About | Fidelio | Economy | Strategy | Justice | Conferences | Join

Highlights | Calendar | Music | Books | Concerts | Links | Education | Health

What's New | LaRouche | Spanish Pages | Poetry | Maps

Dialogue of Cultures

© Copyright Schiller Institute, Inc. 2003. All Rights Reserved.