Home | Search | About | Fidelio | Economy | Strategy | Justice | Conferences | Join

Highlights | Calendar | Music | Books | Concerts | Links | Education | Health

What's New | LaRouche | Spanish Pages | Poetry | Maps

Dialogue of Cultures

|

||||

|

Mikhail Yurievich Lermontov

|

||||

The Promise of Mikhail Lermontov

by

Denise M. Henderson

For related articles, scroll down or click here.

Denise Marguerite Dempsey Henderson, a long-time associate of Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr.,was struck and killed in a hit-and-run accident in Washington, D.C. on September 15, 2003. For over 20 years, Mrs. Henderson helped man the Russian/Eastern Europe desk of Executive Intelligence Review, as well as undertaking other editorial assignments, including Editorial Assistant of Fidelio Magazine. This article, on the political and cultural significance of Russia's Mikhail Lermontov, was drafed in November 2002. Preparation for publication has been aided by Denise’s colleague and friend Rachel Douglas, who provided assistance with the translations and editorial details, as well as supplying the boxed background material. |

|||

Suppose you found yourself in a society where the accepted way of doing things was no longer sufficient? Suppose that, with the loss of key individuals in your society, a crisis which could affect the survival of your nation was fast approaching, and you were one among the few, willing to say that there had to be a change, as soon as possible, in how things got done?

Suppose also that many of your co-thinkers or potential collaborators had been assassinated or rendered ineffective by enemy operations? Could you then, still, not merely say what you knew to be true, but act on the ideas which you knew could move the existing context into a completely new and much more fruitful direction?

This was the situation in which the 23-year-old poet Mikhail Lermontov found himself in 1837, when Alexander Pushkin (see Pushkin box) was murdered in a duel. For by then, not only Pushkin, but also Alexander Griboyedov, the Russian emissary to Iran and author of the play Woe from Wit, had been murdered: Pushkin in a duel he shouldn’t have fought, and Griboyedov along with the rest of the embassy staff at the Russian embassy in Iran (then Persia) by an enraged mob.

Lermontov, despite this, and under these conditions, in his poetry and essays wrote about the dearth of consistent, clear leadership in Russia under Tsar Nicholas I, echoing many of Pushkin’s themes and continuing the development of the Russian language and Russian poetry. Lermontov also reflected the influence of the German Classical tradition on Russia, through his study of the writings of Schiller and Heine, as well as by translating their works into Russian.

Mikhail Lermontov was born in 1814, fifteen years after Pushkin. He found himself in a Russia where the political situation had largely deteriorated, thanks to the rigidities of Nicholas I and many of the Tsar’s closest advisers, including the cruel Minister of War, General Alexei Arakcheyev, and the anti-republican Foreign Minister Nesselrode, along with the salon of Madame Nesselrode. The Russian Army in the Caucasus, where Lermontov was to spend most of his military service, found itself engaged in a brutal, protracted guerrilla war. On the one hand, the local population had been encouraged by various leaders to fight to the death, while on the other, the Russian Commander, General Yermolov, in response, had begun to pursue a slash-and-burn policy that demoralized the Russian officer corps that had hoped for liberalization and change after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815.

Lermontov was steeped in the Classics from an early age, and this led him to develop his ability to assimilate several languages, including Latin, Greek, French, German, and English. Lermontov also read everything by Pushkin that he could get his hands on. Although Lermontov and Pushkin attended many of the same theaters, ballets, and so forth, they never met. However, Pushkin, having received some unedited poems by Lermontov, told his friend, the musician Glinka, “These are the sparkling proofs of a very great talent!”

| Will you, poet, who is mocked, reawake! Or, will you never avenge against those who spurn— From the golden scabbard unsheath your blade, Covered with the rust of scorn? from ‘The Poet,’ 1838 |

||||

|

||||

|

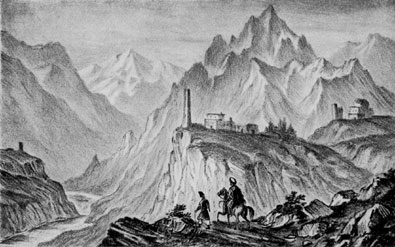

View of Mt. Kreshora from the gorge near Kobi, the Caucasus. Drawing by M. Lermontov.

|

||||

Schiller’s “The Glove,” is about a would-be enchantress at the court, who is not successful in ensnaring the knight, her prey. Lermontov’s translation of “The Glove” is a full translation from German into Russian of Schiller’s original poem, which mocks those who would cater to the fashions of the court. In it, a knight risks his life by entering the cage of a tiger at a tournament to retrieve a lady’s glove.

. “And from the monstrous middle racing,” writes Schiller,“Grabs he the glove now with finger daring. ...”What happens next, however, takes the court completely by surprise.

Then from every mouth his praises shower,

But to one the loving glance most dear—

Which promises him his bliss is near—

Receives he from Cunigund's tower.

And he throws in her face the glove he's got:

“Your thanks, Lady, I want that not.”

And he leaves her that very hour!

(Translation by Marianna Wertz)

In other words, the knight walks away from the established customs and “way things are done,” without a second glance. He refuses to be a plaything of the oligarchy.

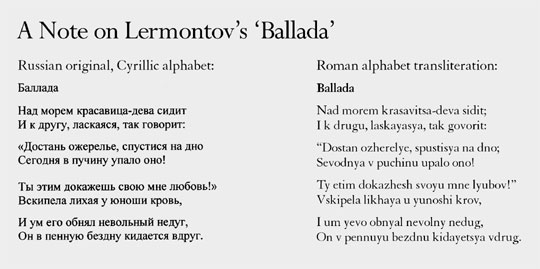

In “Ballad,” Lermontov used Schiller's “The Diver” as his source, but cut out the king as instigator of the diver's ill-fated journey. Instead, he focusses on the idea of the enchantress who views her “dear friend” as a plaything. The poem was probably written in 1829, the same year Lermontov translated “The Glove.” In “Ballad,” Lermontov took further in Russian the rhymed couplet form which Pushkin had sometimes used, but which Heine to a greater degree had been developing in the German language. (see note on “Ballad”)

The Ballad

Sits a beauteous maiden above the sea,

And to her friend doth say, with a plea

“Deliver the necklet, it’s down in the drink,

Today into the whirlpool did it sink!

“And thus shalt thou show me thy love!”

Wildly boiled the young man’s blood,

And his mind, unwilling, the charge embracing,

At once into the foamy abyss he’s racing.

From the abyss doth fly the pearl spray,

And the waves course about, and swirl, and play,

And again they beat as the shore they near,

Here do they return the friend so dear.

O Fortune! He lives, to the cliff doth he cling,

In his hand is the necklet, but how sad doth he seem.

He is afraid to believe his tired legs,

The water streams from his locks down his neck.

“Say, whether I do not love thee or do,

For the beautiful pearls my life I spared not,

“As thou said, it had fallen into the black deep

It did lie down under the coral reef—

“Take it!” And he with a sad gaze turned

To the one for whom his own life he spurned.

Came the answer: “O my youth, O dear one!

If thou love, down to the coral go yet again.”

The daring youth, with hopeless soul,

To find coral, or his finish, down dove.

From the abyss doth fly the pearl spray,

And the waves course about, and swirl, and play,

And again do they beat o’er the shore,

But the dear one return not evermore.

(Translation by the author)

(See Note on Ballad)

Tragically, at the crucial moment, Lermontov himself failed to escape the trap which had been set for him. For, once he had written his poem, “<i>Death of</i>A Poet” about Pushkin’s murder, and its postscript, written with the knowledge of who was behind the calumnies that led to Pushkin’s duel and death, Lermontov allowed himself to be ensnared by those in the Russian court and establishment who did not want there to be any successor to the freedom-loving Pushkin, and as a result he was shot dead in a duel in the Caucasus in 1841—four years after Pushkin’s own death in a duel.1

Who Was Mikhail Lermontov?

Mikhail Lermontov, or “Mishka” as he was known as a child, was born in 1814, in Penza, a village to the southeast of Moscow. His grandmother, Elizabeth Alexeyevna Arsenyeva (née Stolypina), who was the major landholder in Pskov, had opposed the marriage of her daughter “beneath her station” to a Russian Army officer, Yuri Petrovich Lermontov, and did everything she could to break up the marriage by whispering in her daughter’s ear what a bad match Yuri was for her.>

Mishka thus grew up in a household permeated by strife. At first, there was the growing conflict, incited by Elizabeth Alexeyevna, between his father, Yuri Petrovich, and Maria Mikhailovna, his mother, who suffered from tuberculosis. Mishka seems to have cared about both his parents, and actually wrote a poem to his deceased mother in 1834, which, according to an entry in his diary, is based on the remembrance he had of his mother singing to him when he was three years old.

“The Angel,” describes the individual who cannot forget the music of the heavenly spheres.

The Angel

An angel flew in the midnight sky,

And sang a lullaby;

And all around, the stars and the moon,

Heeded that holy song.

He sang of the blessedness of the innocent,

’Neath Eden’s tents,

About the great God he sang,

And his praise was unfeigned.

A young soul he held in his hands,

For the world of tears and sadness,

And the sound of his song in the young soul

Remained—without words, but whole.

And for a long time on earth that soul stayed,

But never could he trade

Heaven’s music, soaring,

For the songs of earth so boring.

With his parents estranged by the time he was three, Mikhail began suffering bouts of nerves. Maria Lermontova soon discovered that music, the playing of the old songs, the “ingenious cavalcade of notes,” as biographer Henri Troyat calls it, calmed her son’s nerves.

At his mother’s death, Lermontov’s grandmother took charge of Mishka’s person and education. The domineering Elizabeth Alexeyevna, taking advantage of Yuri’s grief and the fact that he was in debt, drove him out of his own son’s life. At the same time, Lermontov’s grandmother wound up getting him the best tutors and the best education she could afford, including music lessons, lessons in French, the language of the Russian aristocracy, as well as in Greek, and in painting.

Elizabeth Alexeyevna ensured that her grandson’s health, which was poor when he was a child, was looked after. He visited the Caucasus twice during his childhood, once when he was six and again at the age of 10. He and his grandmother, along with their retinue, went to his aunt’s estate in Georgia, where it was hoped the fresh air and the spas would improve Mishka’s condition.

Lermontov would later remember the excitement of the long trip from Pskov to the Georgian Caucasus, which has often been compared as a frontier to the Wild West of the United States.

At the age of 10, on the second visit, he also perused his aunt’s library, which contained the works of the French (Rousseau, Voltaire), as well as the German poets Schiller and Goethe.

In 1825, Lermontov’s family, like many Russian aristocratic families, was personally affected by the Decembrist uprising of officers in St. Petersburg (see box on Decemberist Uprising). The uprising, sparked by the accession of Nicholas I to the throne, was suppressed, and the officers who led it were arrested. Lermontov’s great uncle, General Dmitri Stolypin—the grandfather of the famous Russian reformer Pyotr A. Stolypin—was sympathetic to the Decembrists and a friend of Decembrist leader Pavel Pestel, who was hanged for his role in the plot.

Lermontov had been given a broad education, both in the Classics and in French Romantic ideas, by private tutors in his grandmother’s home. At the age of 15, he attended the Moscow University Boarding School for Young Men, also known as the Moscow Noble Pension, a private pension in Moscow that focussed on the Classics (a pension being the equivalent of a private preparatory school in the United States). Tsar Nicholas I, having personally visited the school with the head of the Third Department (the secret police), Count Alexander Benkendorf, pronounced the school too liberal. Its professors were ordered to curtail the curriculum.

Because the German Classical movement was radiating outward into Russia, even Moscow, the home of the more traditional Russian elites who were wedded to the landed aristocracy and serfdom, began to see a renaissance in its educational institutions and its cultural outlook. Lermontov benefited both from the Moscow Noble Pension, in which he was enrolled in 1829, and from public performances of Schiller and Shakespeare, even bad or truncated ones. In letters to his aunt, Lermontov roundly criticized a performance of Hamlet, explaining to her that key passages from the original had been consciously omitted.

Throughout his teens, Lermontov continued to compose original poetry and to translate. In 1831, he was enrolled at Moscow University. But, as the first semester proceeded, the cholera epidemic, which had spread from Asia into Russia and would sweep through Poland as well, hit Moscow. Students from the University were enlisted in the fight to stop the spread of the disease, in concert with students from the University’s Department of Medicine. Classes would not resume until the beginning of 1832.

Once classes resumed, Lermontov and his friends, who had participated in beating back the cholera, found it difficult to readjust to the stultified university life, in which anything that smacked of non-autocratic ideas was suppressed. Lermontov and his friends became known as the “Joyous Band.” The group was drawn to ideas of a constitutional state, in which serfdom would be abolished, and where there would be universal education.

Most of the faculty of Moscow University was steeped in a commitment to serfdom and all that this implied for economics, as well as in Tsar Nicholas’s doctrine—actually the doctrine of Nesselrode and the worst oligarchical elements of Imperial Russia in this period—of “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality.” For Nicholas, nationality referred to the Russian as a Great Russian. This was the period when Russia played the role of gendarme of Europe, assigned to it by the masters of power politics—Capodistra, Metternich, Castlereagh—at the 1815 Congress of Vienna, as well as pursuing imperial designs of its own.

In 1831, Lermontov and his friends had already had one encounter with Malov, their professor of Roman law, described as extremely obtuse. On March 16, 1831, they shut down his lecture with hissing, refusing to allow him to continue.

While this incident almost got them sent into the army as common soldiers, Malov was dissuaded from pursuing charges. In a Professor Pobedenostsev’s class, Lermontov responded that his teachers knew nothing, and that rather, he was educating himself from his personal library, which contained much more recent materials in foreign languages. In class after class, Lermontov continued to challenge the authority of professors, who were teaching from outdated materials, and who were attempting to enforce Nicholas’s doctrine of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality. While Lermontov and his Joyous Band may not have had a fully thought-out solution, they had before them the example of the Decembrists, the “first revolutionaries.” And they knew that their education was narrow and ideological.

Lermontov’s continued confrontations with his professors finally led to his expulsion from the University. He planned to transfer to the University in St. Petersburg, but because the credits he had earned at Moscow were not transferrable, he decided instead to enroll in the Junkers Military School. Upon graduation in two years, as the scion of a noble family, he would be able to enroll in one of the regiments of the Guard. This he hoped would be easy duty, relatively speaking, in the vicinity of St. Petersburg.

Lermontov’s enrollment began in November of 1832, in the Hussars of the Guard. At the school, where attempts at liberalism had been shut down by the Tsar, Lermontov was immersed in military studies, including strategy, ballistics, and fortifications. He graduated in 1834.

From 1835 to 1836, Lermontov spent time in St. Petersburg among the social circles of the aristocracy. He wrote much verse, and some of it was noted by the critic Vissarion Belinsky for its conflicting themes of fulfillment and despair.

In 1837, Lermontov, like all Russians, was stunned by the murder of Alexander Pushkin in a duel with the adopted son of the Dutch ambassador to Russia. His poem, “<i>Death of</i>A Poet,” on Pushkin’s murder, would get him imprisoned in the Fortress of Peter and Paul, then exiled to the Caucasus. Having gotten seriously ill with pneumonia and rheumatism on maneuvers, Lermontov, with the agreement of his commander, spent several months at the spa in Pyatigorsk, a rest and social resort for the military and aristocracy.

Finally rejoining his regiment in Tbilisi in October 1837, Lermontov was told that the Tsar had issued an order allowing him to return from exile, and to join a regiment at Pskov. Mikhail, who was writing verse based on tales about the Caucasus, took his time in returning north. He finally arrived in St. Petersburg on January 3, 1838. In April, spurred by his requests to his grandmother and her requests to Grand Duke Michael and Benkendorf, Lermontov was allowed to return to St. Petersburg. It was in this period that Lermontov wrote A Hero of Our Time. It was completed and published in 1839. Lermontov also wrote his long poem, or “Eastern tale,” as he called it, “The Demon.”

In 1840, Lermontov was again exiled to the Caucasus, this time over a duel that was planned between himself and the son of the French ambassador, Ernest de Barante. The duel took place in February. No one was hurt, but when the duel was discovered, Lermontov was arrested and exiled. This time, no appeal from Elizabeth Alexeyevna could prevent his exile.

On April 16, 1840, while Lermontov was in prison awaiting court-martial, the critic Belinsky (with whom he had had disagreements) visited him. Belinsky wrote after this meeting, “Oh, this will be a Russian poet on the scale of an Ivan the Great! Marvellous personality! . . . He reveres Pushkin and likes Onegin best of all. . . .”

Lermontov was found guilty of dueling, and exiled.

He arrived in Stavropol, military headquarters for the Caucasus, in mid-June of 1840, and presented himself to the commander-in-chief of the region, General Grabbe. In this second tour, Lermontov was involved in several military actions. In fact, Lermontov requested active duty, in the hope of receiving a pardon through his exploits, which would allow him to return to St. Petersburg, where he could socialize with the political and social circles that were trying to implement reform.

On July 6, 1840, he fought and acquitted himself well in the battle of Valerik. Then, on October 10, Lermontov took command of what was essentially a Russian Army guerrilla unit, attempting to fight the irregular war in the Caucasus through more flexible tactics.

In November of 1840, Lermontov was recommended for the Order of Saint Stanislas after the Valerik campaign. But in early 1841, Nicholas I denied him the Order because of his writings. Lermontov was given a two-month pass to St. Petersburg, which he hoped to make permanent.

But by March of 1841, Lermontov realized that he would not be permitted to remain in the capital, and went to rejoin his regiment. Once he arrived in Stavropol, he had himself placed on sick leave, and went to Pyatigorsk.

During this time, Lermontov was under surveillance by the secret police of the Third Department. On July 13, 1841, at a party arranged by Lermontov, Lermontov and “Monkey” Martynov, a former classmate and friend, had a minor argument. A duel was set for July 15.

Lermontov spent the next two days attempting to resolve the matter, and avoid the duel. But Martynov refused to come to any accommodation.

On July 15, the duel took place. Lermontov either refused to fire or fired into the air. Martynov, hesitating only a moment, shot the poet dead.

Lermontov’s Poetry

And when Raphael, so inspired,

The pure Virgin’s image, blessed,

Completed with his brush afire,

By his art enraptured

He before his painting fell!

But soon was this wonderment

In his youthful breast tamed

And, wearied and mute,

He forgot the celestial flame.

Thus the poet: a thought flashing,

As he, heart and soul, his pen dashing,

With the sound of his famed lyre

Charms the world; in quiet deep

It sings, forgetting in heavenly sleep

Thou, thou! The idol of his soul!

Suddenly, his fiery cheeks grow cold,

All his tend’rest passions

Are quiet, and flees the apparition!

But how long, how long the mind holds

The very first impression.

—M.I. Lermontov (approx. age 16)

In 1838, with Pushkin dead for about a year, the 24-year-old Lermontov wrote another poem titled “The Poet,” which was his reflection on what it meant to be a poet during the reign of Nicholas I. This poem begins in the first person. A Cossack who has retired from fighting, has hung up his battle-worn kindjal (a type of knife/sword used in the Nineteenth century in the Caucasus), which now hangs as an ornament on his wall. Lermontov uses this as a metaphor for how poetry, instead of being an instrument with which to rally the troops, and of truth/beauty, has become a party game, or an ornament for the court; therefore rusted, and of no use in the heat of battle. Here are the last five of its 11 stanzas.

from The Poet

In our age effeminate, is it not so, poet,

Lost is your intent,

Having exchanged gold for that portent,

Which the world heeded in reverence silent?

Once it was, the measured sound of your words bold

and loud,

Inflamed for battle the warrior,

Like a cup for the feasts, ’twas needed for the crowd—

Like incense in the hour of prayer.

Your verse, like a holy spirit, floated above them,

Blessed thoughts recalling

That rang like the bell for meeting

In the Days of Troubles—and of national feasting.

But we are bored by your proud and simple words,

We are diverted by tinsel and clouds;

Like a worn-out beauty, is our worn-out world

Used to wrinkles hidden under rouge...

Will you, poet, who is mocked, reawake!

Or will you never avenge against those who spurn,

From the golden scabbard unsheathe your blade,

Covered with the rust of scorn?

—Lermontov, 1838 (Pushkin dead for less than a year)

(Translation by the author)

Thus, under Nicholas’s reign, Lermontov was faced with a paradox. How could he, as one individual, make a difference in an autocratic regime? Like all Russians, he was faced with the murder of Pushkin; with the irregular war in the Caucasus, which would turn into a full-blown war that, at the least, the British imperial faction was able to manipulate a decade or so later; and with the pettiness and contradictions of life under Tsar Nicholas I. It therefore appeared that to be a thinking, creative person, was to be put in the position of becoming an outcast—someone who, in the eyes of society, would be considered a beggar standing naked in the town square, attempting to tell the truth to an audience which was either too frightened, or too consumed with its own private games, to listen.

The Prophet

E’er since the judge eterne

The prophet’s omniscience gave me,

In people’s eyes do I discern

The pages of malice and enmity.

To proclaim love I came

And the pure truths of learning:

All my neighbors, enraged,

At me stones were hurling

With embers I strewed my head,

From the cities did I flee

And thus I live in the desert;

Like the birds, on food divine and free.

Earth’s obedient creature

Of the eternal preserver calls to me

And the stars do hear,

Their rays play joyfully.

And so in the noisy town, while

I hastily make my way,

With a self-satisfied smile,

Then the old men to the children say:

Look: Here’s an example for you!

He was proud, and did not dwell among us:

He wanted us to believe—the fool—

That God speaks with his lip!

And, children, upon him look:

How ill he is, and ashen,

Look how naked he is, and poor,

How everyone despises him!

—M.I. Lermontov, 1841

The turmoil Lermontov faced as a young man, both in his personal life and in the military, was reflected in the three-stanza poem “The Sail,” which uses the metaphor of a sailing ship steering into a storm, “as if in storms there is peace.” That is, as many a sailor knows, if you cannot outrun a storm, you must navigate through it, if you are to return home safely.

The Sail

Gleams white a solitary sail

In the haze of the light blue sea.—

What seeks it in countries far away?

What in its native land did leave?

The mast creaks and presses,

The wind whistles, the waves are playing;

Alas! It does not seek happiness,

Nor from happiness is fleeing!

Beneath, the azure current flows,

Above, the golden sunlight streaks:—

But restless, into the storm it goes,

As if in storms there is peace!

—M.I. Lermontov, 1832 (18 years old)

(Translation by the author)

Lermontov became quite visible—and a target of both international and Russian political forces which were behind Pushkin’s murder—with “<i>Death of</i>A Poet,” a passionate eulogy on Pushkin’s death. Lermontov had read many handwritten copies of Pushkin’s poems, passed from person to person, during these years. As his writings attest, Lermontov certainly understood what Pushkin’s groundbreaking work in the Russian language meant for Russia. Lermontov also attended balls and gatherings among the officer corps stationed in St. Petersburg, at which Pushkin was present. But he wanted any meeting with Pushkin to be peer to peer, poet to poet, and so stayed in the background whenever Pushkin was present.

<i>Death of</i>A Poet

The poet’s murd’red!—slave of honor,

He fell, by rumor defamed,

With lead in the breast, and his proud head bowed

By a thirst for vengeance!

The poet’s soul had not withstood

The disgrace of petty-minded insults.

He rose against the opinion of the world

Alone, as formerly . . . and he’s murdered!

Murdered! . . . Now to what purpose is sobbing,

A useless chorus of empty praises,

And the pitiful prattle of excuses?

Fate’s sentence has been imposed!

Was it not you who first thus persecuted

So cruelly his free, bold gift,

And for amusement fanned

The fire that had somewhat abated?

So? Be happy. . . . He could not

Bear the final torments.

Extinguished, like a lamp, is the

Marvellous genius,

Withered the ceremonial crown.

His murderer, coldblooded,

Took aim . . . There was no salvation:

That empty heart beat steadily,

In the hand the pistol did not tremble

And how is that strange? From afar,

Like a thousand fugitives,

He, hunting for fortune and rank,

Thrown among us by the will of fate

Laughing, impudently despised

The language and customs of this alien land;

He could not spare our glory,

He could not understand in that bloody instant,

Against what he raised his hand!

And he is slain—and taken to the grave,

Like that bard, unknown but dear,

The prey of dull envy,

Whom he praised with such wonderful force,

Struck down, like him, by a pitiless hand.*

Why from peaceful delights and open-hearted friendship

Did he enter into this envious world—stifling

For a free heart and fiery passions?

Why did he extend a hand to petty slanderers,

Why did he believe the false words and caresses,

He, who from his youthful years understood people?

They removed the former garland, and a crown of thorns

Entwined with laurel put they on him:

But the secret spines harshly

Wounded the famous brow;

His last moments were poisoned

By the insidious whispers of derisive fools,

And he died—thirsting in vain for vengeance,

Secretly besieged by false hopes.

The sounds of his wonderful songs fell silent,

They will not ring out again:

The bard’s refuge is cramped and sullen,

And his lips are sealed.

(Translation by the author)

Lermontov might have been considered a minor irritation and been reprimanded had he left his poem there. But he decided to go all the way in a postscript written several weeks later, and attack the court itself for its organized role in Pushkin’s death. The postscript was then surreptitiously circulated to trusted friends. At the time, Benkendorf took it as “seditious” and a “call to revolution.”

And you, stubborn heirs

Of fathers renowned for meanness,

Who with servile heel trod underfoot the shards

Of families by Fortune frowned upon!

You, greedy crowd standing near the throne,

Of Freedom, Genius and Glory the hangman!

You hide behind the protection of law,

Before you, the court and truth—all is silent!

But there is also divine judgment, you cronies of corruption!

There is a terrible judge: he waits;

He is not swayed by tinkling gold,

And knows your thoughts and affairs beforehand.

Then in vain will you resort to slander:

It will not help you again,

And with all your black blood you shall not wash away

The righteous blood of the poet!

One of Lermontov’s cousins, Nicholas Stolypin, described by one Lermontov biographer as “a smart young diplomat serving in the Foreign Ministry of von Nesselrode”—i.e., the same Nesselrode whose wife’s salon had been at the center of the operation against Pushkin—visited Lermontov to harangue him and tell him he had gone too far, and that he should cease and desist attacking the Tsar and the court immediately. Lermontov angrily replied: “You, sir, are the antithesis of Pushkin, and if you do not leave this second, I will not answer for my actions.” Even with the limited circulation of the postscript, Lermontov had sealed his fate. He and his friend Svyatoslav Rayevsky, who had circulated the postscript to various people, were immediately arrested. Rayevsky attempted to send a letter to Lermontov warning him to make sure that their stories were the same. But the letter was intercepted. Each was interrogated individually, and made to admit the role of the other in the circulation of the postscript. Lermontov and Rayevsky wound up being imprisoned at the Fortress of Peter and Paul for six months. Lermontov was made to write a statement of contrition, addressed to Nicholas I, in which he praised Nicholas’s generosity to Pushkin’s widow and children. At the end of the statement, however, Lermontov proved himself to be committed to what he had previously written. “As far as concerns me personally,” he wrote, “I have not sent this poem out to anyone, but in acknowledging my inconsequence, I do not want to disavow it. The truth has always been sacred to me and now in offering my guilty head for judgment, I have recourse to the truth with firmness as the only protector of an honest man before the Tsar and before God.” Because of pleas on his behalf by his grandmother, given her position in society, and by the court poet Zhukovsky, Lermontov did not wind up in Siberia. Instead, he was exiled to the Caucasus as a member of the Nizhny Novgorod Dragoons. Thus, at the age of 23, Lermontov was to return to the region where he had spent several summers of his youth on his aunt’s estate. There, Lermontov was to meet and become re-acquainted with members of the Caucasian Officer Corps, made up almost entirely of those officers exiled by Nicholas I for their role in the Decembrist uprising of 1825, and many of whom he knew or had been friends of Pushkin.

The Caucasus

In 1840, Lermontov, while in St. Petersburg, was challenged to a duel. While some in the court tried to claim that the duel was personal, those closer to Lermontov asserted that Lermontov was challenged over his blunt, public stance on the de facto murder of Pushkin. When it was “discovered” that Lermontov had been duelling, he was thrown in prison, and exiled again to the Caucasus. One of Lermontov’s most poignant poems, written upon his second exile, reflects the conditions to which Russians knew themselves to be subject, i.e., that there were police spies everywhere. Lermontov called Russia, the land of “all-hearing ears.”

Farewell, unwashed Russia,Land of slaves, land of lords,

And you,* blue uniforms,

And thou, a people devoted to them.

Perhaps, beyond the wall of the Caucasus,

I will be concealed from your pashas,

From their eyes all-seeing,

And ears all-hearing.

—1841

(translation by the author)

(Translation by the author)

Thus, Lermontov spent most of the years 1837 to 1841—the remainder of his short life—as an officer in the Caucasus, with a short return to the capital, St. Petersburg, engineered by his grandmother in 1839. And upon his return to St. Petersburg, Lermontov wrote A Hero of Our Time.

A Hero of Our Time

The final straw for those among Russia’s ruling elite who were committed to an anti-republican outlook, and thus determined to be rid of Lermontov, was Lermontov’s novella, A Hero of Our Time, often classified simply as “the first modern Russian psychological novel.”

But, although Lermontov does describe the psychological ills of his fellow Russian officers stationed in the Caucasus, that is not the only purpose of Hero. A Hero of Our Time is an example of why it is not enough to read the text of an author literally. The analysis situs—that is, the historical time and place—in which Lermontov wrote Hero, is crucial to an understanding of why Lermontov addressed the question of the state of mind of the Russian officer corps so harshly.

Lermontov saw military action in the Caucasus(See Box on Caucasus). Additionally, he had had not only access, but opportunity to talk to some of the battle-tested generals in the Caucasus about the guerrilla war there. Thus, Hero’s larger purpose, based on Lermontov’s own experience in and knowledge of the Caucasus, as well as these discussions with experienced military leaders, was to attempt to convey to Nicholas I the conditions festering among the officer corps on Russia’s crucial “southern flank,” who were forced to fight a brutal irregular war on difficult terrain, in a tropical climate where disease killed as many men as the fighting did. Additionally, this guerrilla war was being supported with money and materiel from outside Russia and the Caucasus.

Lermontov’s introduction to the second edition of Hero is rather direct and blunt. He writes: “It is a pity, especially in our country, where the reading public is still so naive and immature that it cannot understand a fable unless the moral is given at the end, fails to see jokes, has no sense of irony, and is simply badly educated,” that the reading public ignores the preface to books.

Written with a red-hot sense of irony, on the heels of Pushkin’s murder and his own exile, Lermontov continues:

Our country “still doesn’t realize that open abuse is impossible in respectable society or in respectable books, and that modern culture has found a far keener weapon than abuse. Though practically invisible it is none the less deadly, and under the cloak of flattery strikes surely and irresistibly.” And what is the reaction of the “reading public”? Writes Lermontov, again ironically, it “is like some country bumpkin who hears a conversation between two diplomats from opposing courts and goes away convinced that each is betraying his government for the sake of an intimate mutual friendship.”

Nicholas I, as he did with Pushkin’s writings, personally read and censored Lermontov’s Hero. The Tsar complained that the main character, Pechorin, was a poor representative of what a Russian officer should be.

Thus, writes Lermontov, “The present book, recently had the misfortune to be taken literally by some readers and even by some journals. Some were terribly offended that anyone as immoral as the Hero of Our Time should be held up as an example, while others very subtly remarked that the author had portrayed himself and his acquaintances. Again that feeble old joke! Russia seems to be made in such a way that everything can change, except absurdities like this, and even the most fantastic fairy-tale can hardly escape being criticized for attempted libel.

“The Hero of Our Time is certainly a portrait,” explains Lermontov, “but not of a single person. It is a portrait of the vices of our whole generation in their ultimate development. You will say that no man can be so bad, and I will ask you why, after accepting all the villains of tragedy and romance, you refuse to believe in Pechorin,” at whose portrayal as a cynical, self-absorbed, disgruntled Russian officer Nicholas I took extreme umbrage. It may be that Lermontov is asking Nicholas to look in the mirror: “You have admired far more terrible and monstrous characters than he is, so why are you so merciless towards him, even as a fictitious character? Perhaps he comes too close to the bone?”

Finally, writes Lermontov in this introduction, “you may say that morality will not benefit from this book. I’m sorry, but people have been fed on sweets too long and it has ruined their digestion. Bitter medicines and harsh truths are needed now, though please don’t imagine that the present author was ever vain enough to dream of correcting human vices. Heaven preserve him from being so naive! It simply amused him to draw a picture of contemporary man as he understands him and as he has, to his own and your misfortune, too often found him. Let it suffice that the malady has been diagnosed—heaven alone knows how to cure it!” (In fact, it would take Russia’s near-defeat in the Crimean War under Nicholas I, the ascension of Alexander II to the throne, and the resulting upswing in Russian scientific and economic development—as well as the freeing of the serfs—to begin to cure the malady.)

Hero portrays a young officer just arrived in the Caucasus, who is regaled by an older officer with tales of the cynical, self-absorbed Pechorin, who has “gone native,” taken a local princess as his mistress, and then left her. Additionally, the new arrival describes the Caucasus for us, and his journey along the Georgian Military Road to his new post. One of the stories that comprise the novella, “Taman,” about Pechorin’s travels, describes how Pechorin is forced to take shelter in a hut where nothing is as it seems. Seduced by the young woman of the household, Pechorin comes to realize that he has entered a den of smugglers, consisting of the woman, a blind boy, and an old man. Pechorin barely escapes with his life.

The final story in Hero, “The Fatalist,” is as telling as its introduction. Seemingly just a tale of officers playing cards and “Russian Roulette” (possibly the first mention ever made) in a small, isolated village in the Caucasus, who are discussing whether there is such a thing as predestination, the irony of the tale could not have been missed by any Russian soldier or officer who had served any time at all in the Caucasus.

In the story, the officer who draws the round with the bullet in it fires, but the gun misfires, harming no one. He then leaves the card game and gets into a brawl with two drunken Cossacks, who kill him. The protagonist of this story proceeds to capture one of the Cossacks and hold him until the authorities can arrive.

Any Russian who had served in that area would understand immediately what Lermontov was writing about. While you could never be sure if your Russian-made weapon would fire properly, you could be sure that an encounter with a Cossack could be deadly, whether on the town streets or in combat. Many of the guerrillas were armed with Cossack or similar sabers. It was also the preferred weapon of Russians stationed in the Caucasus for more than a few months, since they knew it was swift, sure, and reliable.

During his brief return to St. Petersburg, Lermontov discussed and wrote about how he would like to write a novel based on the history of Russia from the time of the Pugachov rebellion of 1771 to the Napoleonic Wars (1805 and 1812-1815), and Russia’s victory (with significant military-strategic help from certain key Prussian officers) over Napoleon’s army. This project, which would have taken up where Pushkin left off with his History of Pugachov, was never completed, owing to Lermontov’s death in 1841. Lermontov also wanted to write a biography of Griboyedov, the exiled playwright who, along with the rest of the mission, was tragically murdered in Teheran.

During Lermontov’s stay in St. Petersburg, forces behind the scenes had determined to remove him from the environs of the court. Lermontov was headstrong, and still angered by Pushkin’s murder. Because of his knowledge of the role of the Nesselrode salon in Pushkin’s murder, he had never succumbed to the official story, that the duel was over a “private matter.” He was often seen at the balls and parties of Pushkin’s friends.

In 1841, four years after the death of Pushkin and two years after Lermontov’s exile to the Caucasus, Lermontov, taking a cure at the spa in Pyatigorsk, found himself facing off in a duel against Major Martynov, whom he had in fact tried to placate after a minor quarrel. But Martynov demanded satisfaction (there is some evidence he was being directed by agents of Russia’s secret service, the Third Department).

A housemate of Martynov’s, a prince named Vasilchikov, whom Lermontov had known since 1837, told Lermontov that he had arranged a compromise. The parties would meet for the duel as scheduled, and each party would fire into the air. They would then shake hands and part.

But, whether Vasilchikov was a witting or unwitting accomplice, that is not what happened. Lermontov fired first, firing his shot into the air, as had been worked out, he believed, with Vasilchikov. Martynov hesitated, then, claiming that Lermontov had insulted him yet again, shot Lermontov dead.

Thus Mikhail Lermontov, who, at 26 years of age was seen by most of Russia’s intelligentsia as Pushkin’s immediate heir, went to his death on July 15, 1841.

Upon hearing the news, Nicholas I was reported to have said, “Gentlemen, the man who could have replaced Pushkin for us is dead.” Given that the streets outside Pushkin’s home had been lined with ordinary Russians who loved his poetry and were hoping he would recover after his duel, Nicholas must have known the effect his remark would have.

But Lermontov’s poetry, like Pushkin’s, lived on, both by itself, and also through music. It is reported that Lermontov set his own poems to music, most of which settings have unfortunately not survived. However, the Russian composer Glinka set to music many of Pushkin’s poems, and several of Lermontov’s, in the first half of the Nineteenth century, in the tradition of the German Classical lieder. Glinka set a poem by Lermontov called “Prayer,” as well as setting many of Zhukovsky’s Russian translations of Schiller poems. Thus, there is a direct transmission belt from German Classical poetry, to German Lieder, to the transmission of that by Glinka into the equivalent of Russian Lieder. (It should also be noted that Glinka also set the poetry of Pushkin’s good friend Baron Delvig. Delvig was second-in-command on the first railroad building project in Russia.)

What we have available to us today of Lermontov’s body of work, indicates a great potential cut short by his early death. Pushkin himself recognized Lermontov’s “sparkling” talent. It is clear that Lermontov was beginning to mature, and that he would have been able to continue to develop the tradition of Pushkin. As with Pushkin, Lermontov wanted to write for Russia a portion of its universal history, with an eye toward transforming the way Russians saw themselves.

After Lermontov, there would be others. There was Gogol, whose Dead Souls was explicitly conceived to be a Russian Divine Comedy, although never completed. There was also to be Goncharov, author of Oblomov, a novel which satirized the do-nothing, lying-in-bed-all-day, would-be reformers among the Russian oligarchy. There was the biting satire of Saltykov-Shchedrin, as well as What Is To Be Done? by Chernyshevsky, from which Vladimir Lenin would take the title for one of his key political tracts. Similarly, in Ukraine, there were to be a number of significant Ukrainian poets and translators of Heine and Schiller.

Thus, the cultural and literary movement created by Pushkin and his friends, of which Lermontov was a part, lived on through several generations. And through the spirit of a new renaissance today, it can continue to live on in the work of a new generation of poets and musicians.

|

Footnotes |

||

1. The political circumstances surrounding Pushkin's death are reviewed by Vadim V. Kozhinov in “The Mystery of Pushkin's Death,” in the “Symposium: Alexander Pushkin, Russia's Poet of Universal Genius,” Fidelio, Fall 1999 (Vol. VII, No. 3). The Symposium presents discussion of Pushkin's life and work in “The Living Memory of Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin” (Rachel B. Douglas), “Pushkin and Schiller” (Helga Zepp LaRouche), and “ Pushkin Was a Live Volcano ...' ” (E.S. Lebedeva).

|

Boxes |

|||

When Lermontov came on the scene, Russian's master poet, Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (1799-1837), was still alive to work his magic. As he composed the greatest works of Russian poetry and launched the development of literary prose, Pushkin transformed the Russian language, and Russia. His beautiful language is the core of literate Russian to this day.

|

|||

|

Alexander Pushkin

|

|||

Exploring the paradoxes of leadership in Russian history, Pushkin pioneered Classical tragedy in the Russian language, with his drama Boris Godunov and his studies of Czar Peter the Great. He was a master of the acerbic epigram, aimed at political or cultural foes. He was one of the great story-tellers of all time.

Never far from politics, Pushkin had close friends among the young officers of the Decembrist movement, whose uprising was crushed in 1825. He was no mere rebel, however, but sought ways to influence Czar Nicholas I (r. 1825-1854) in the direction of peaceful reform, centered on education. Pushkin's murder by Georges d'Anthes in a duel was the project of a powerful clique of foreign-connected oligarchs, who ran Russian much of Russian policy in the period after the 1815 Congress of Vienna.

—Rachel Douglas

At a crossroads of Eurasia between the Black Sea and the Caspian, lies the Caucasus mountain range. Topped by the highest peak in Europe, 18,841-foot Mt. Elbrus, the terrain is rugged. Mt. Kazbek in the Caucasus is where Prometheus, in legend, was chained to a rock for eternity. To the south, in Transcaucasia, lie the ancient Christian nations of Armenia and Georgia. The gorges between the mountains have been inhabited by scores of peoples, with diverse religions and loyalties, over the centuries: Chechens, Circassians, and many others.

The Caucasus and Transcaucasia came under Russian rule over a period of several centuries, and eventually were part of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. King Irakli II of Georgia began the process of Georgia's annexation to Russia in 1784, seeking protection from the Caucasus mountain fighters, often directed by the Turkish Sultan—or his European controllers in a given era—in their raids against Georgia. In the late Eighteenth century and throughout the Nineteenth, the Russian Empire faced insurgencies in the Caucasus. The Russian military class known as the Cossacks, who had traditional home bases in the plains just to the north of the mountains, were primary combatants in Russian clashes with Caucasus bands, but regular Army troops were also stationed along a string of mountain forts. In 1829, under General Yermolov, Russia secured relative control of the Caucasus.

The Caucasus was Russia's southern frontier, a zone of contests not only with the Ottoman Empire and the Shahs of Persia, but also with the upper reaches of Britain's Imperial power, radiating up from India: the battle for power in Eurasia, known as “The Great Game.” Accordingly, the area was—and still is--a battleground for the intrigues of intelligence services, where things are rarely what they seem to be at first glance. The notorious case in point in the late Eighteenth century was Sheikh Mansur, leader of Chechen Muslim fighters against Russia under Catherine the Great: he was a former Dominican monk named Giovanni Battista Boetti, who hailed from Italy via the Levant. In the 1990's, foreign involvement in Chechnya's secession from Russia provided many echoes of such Caucasus traditions.

—Rachel Douglas

The Russian Army, in which Lermontov served, policed the borders of an Empire in the period of the Holy Alliance. The troops were conscripted into virtually life-long service (terms of 25 years, and longer), but the officer corps was the locus of considerable free-thinking. From the ranks of Russian Army leaders came patriotic reforms, as well as a fair share of hotheads with Jacobin leanings. Both elements were present in the famous Decembrist uprising of 1825.

Czar Alexander I died on Nov. 19 (Old Style), 1825 in Taganrog. It was not generally known that his next oldest brother, Governor-General of Warsaw Constantine, had renounced the throne, and a third brother, Nicholas, was the heir. Military units swore allegiance to Constantine, who, however, refused to come to St. Petersburg. On Dec. 14, the Northern Society of young noblemen and officers, veterans of the Great Patriotic War against Napoleon, took advantage of the interregnum to stage a revolt against the incoming Czar Nicholas I. On the Senate Square in St. Petersburg, a day-long standoff, punctuated by the assassination of two government officials, ended in an hour of cannon fire. Scores of the soldiers summoned by the insurgents died, and the Decembrist leaders were arrested. Five ring-leaders were hanged in 1826, including the poet Kondrati Ryleyev. Others were exiled to Siberia for life.

The mission and the fate of the Decembrists preoccupied Russia's intellectuals and writers, beginning with the friend of many of them, Pushkin. It loomed large for the generation of Lermontov, who had been 10 years old in 1825, and took his military commission in 1834.

—Rachel Douglas

|

Notes |

|||

Lermontov uses the polite form of “you” in Russian in the first instance, and the familiar form of “thou” in the second instance. The blue uniforms are those of the Third Department secret police.

back to article

Reference to Eugene Onegin, Pushkin's novel in verse, the duel between Onegin and the poet Lensky, whom Onegin murders

back to article

Special FIDELIO Symposium on Pushkin

Fidelio Table of Contents from 1992-1996

Fidelio Table of Contents from 1997-2001

Fidelio Table of Contents from 2002-present

Join the Schiller Institute,

and help make a new, golden Renaissance!

MOST BACK ISSUES ARE STILL AVAILABLE! One hundred pages in each issue, of groundbreaking original research on philosophy, history, music, classical culture, news, translations, and reviews. Individual copies, while they last, are $5.00 each plus shipping

Subscribe to Fidelio:

Only $20 for 4 issues, $40 for 8 issues.

Overseas subscriptions: $40 for 4 issues.

PO BOX 20244

Washington, DC 20041-0244

703-297-8368

schiller@schillerinstitute.org

Home | Search | About | Fidelio | Economy | Strategy | Justice | Conferences | Join

Highlights | Calendar | Music | Books | Concerts | Links | Education | Health

What's New | LaRouche | Spanish Pages | Poetry | Maps |

Dialogue of Cultures

© Copyright Schiller Institute, Inc. 2004 All Rights Reserved.