Home | Search | About | Fidelio | Economy | Strategy | Justice | Conferences | Links

LaRouche | Music | Join | Books | Concerts | Highlights | Education | Health

Spanish Pages | Poetry | Dialogue of Cultures | Maps

What's New

|

||||

| Amelia Boynton Robinson on Martin Luther King Day in 2004. |

||||

Winning the Right To Vote The Battle for Selma

by Amelia Boynton Robinson

The following is an excerpt from Bridge Across Jordan, by the world-renowned Civil Rights heroine Amelia Boynton Robinson, who played a leading role in the battles that led to the watershed Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act, signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on Aug. 7, 1965. Mrs. Boynton Robinson has dedicated her life to the struggle for human rights, and is today a leading collaborator of Lyndon LaRouche and Helga Zepp-LaRouche.

The sections reproduced here are from Bridge Across Jordan, Part IV: The Battle for Selma.

First Steps Toward Freedom

Man must evolve for all human conflict a method which rejects revenge, aggression, and retaliation. The foundation of such a method is love.

—Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

In October 1962, Bernard Lafayette, a former Fisk University student active with SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference), came to Selma and spent a few weeks studying the condition of the black community. On Thanksgiving of the same year, Bernard left and returned with his wife Colia. She was a college student, young, smart and outgoing, with the gift of vocal communication and a wisdom superior to her age.

Colia drafted a plan to touch every black home in Selma and as far beyond the city limit as her transportation permitted her. No sooner was her plan drawn up than she began to implement it, calling students, girls and boys from 13 to 16 years of age, and sending them in teams to contact occupants of every house. They had them fill out forms, asking name, age, address, occupation, and whether the person was a registered voter. These survey sheets were filed for later use by older surveyors, and thus laid the basis for the survey of the entire city.

In late 1964, students interested in the whole civil rights movement were gathering after school at the home of Mrs. Margaret J. Moore, a teacher, where Bernard Lafayette lived. At this home, the young people were getting acquainted with African-American history and the search for identity, and they were learning freedom songs. Students filled the house at all times.

During this period, the city police, the sheriff, and his deputies constantly patrolled the neighborhood, picking up the youths after they left the house and jailing them. Finally, Mrs. Moore gave one of her rented houses for the activities. Many of the girls were harassed by white men as they walked down the streets in groups. As word spread of the mistreatment, more interest was created among the blacks, and the black crowd seeking justice grew still larger. The First Baptist Church was opened by the Reverend M.C. Cleveland, Jr., and Tabernacle Baptist Church, pastored by the Reverend L.L. Anderson, took care of the overflow. Both churches were open day and night, and both held teaching sessions on nonviolence and the filling in of applications for voter registration. This was before Governor Wallace changed the applications every two weeks and made them several pages long.

The first church in Selma permitting us to have voter education training was that of Reverend Hunter, pastor of the AME Zion church on Lawrence Street. The church was small, but we were warmly welcomed. The second church was First Baptist, followed by Tabernacle Baptist on Broad Street. The participants were so numerous by the latter part of 1964 that, Brown Chapel AME Church being nearer the heart of the city and near First Baptist, the adults were asked to assemble at Brown Chapel, while the youth remained at First Baptist Church. People from the rural sections were much more advanced in voter education, being exposed to their right to vote as well as land ownership for many years by their county agent, S.W. Boynton.

Another phase of the meetings was the teaching of self-control and Christian methods of handling discrimination. During one of these meetings early in 1964, the streets around the churches were patrolled by Jim Clark and his deputies. Their aim was to break up the meetings and send people home in a fright. Clark sent men into the church to pick up the leader of the meeting, but the men did not know him and came back without him. Then Clark himself went in, while the young Reverend Bennie Tucker was on his knees praying. He walked up to the young man, collared him, and dragged him while his deputies cattle-prodded him to the waiting sheriff's car.

Early the next morning, black adults about 400 strong went to the courthouse to register. The courthouse doors were locked and guarded by men with bayonets and shotguns. The people were not allowed to get out of line or hold conversations with passersby or even with the persons next to them. To inconvenience them more, the restrooms were locked and the prospective registrants were not allowed to step out of line at all or they would lose their place in line. Sheriff Jim Clark informed all who were standing that he would jail them for disturbing the peace if they talked.

The sun was hot, the pavement was hard, and there was nowhere to sit. But instead of falling out from exhaustion, they stood like soldiers, hoping, praying, and wishing Jim Clark's heart would soften and that he would open the doors for them to go into the courthouse and register. At 3:30 in the afternoon the people left, not one having had the opportunity to register. - Long Lines To Register -

Every day that the books were open in this spring of 1964, long lines of blacks would brave the wind, the cold, the rain, or the hot sun, only to be humiliated, turned away, or jailed. One hot day in May, while several hundred people were waiting to be registered, a committee including James Forman and John Lewis of SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), Marie Foster, and other workers prepared sandwiches and punch to serve the people who so patiently waited. We took the lunches to the steps of the federal building just across from the courthouse.

I walked over to where Sheriff Clark stood and asked him to permit me to give the people sandwiches and something to drink. He turned as though I had struck him. After he recovered from the shock, he said, “No, I'll be damned if you do.” I told him they had been standing in the hot sun all day, and I wanted to at least give them water. Again he shot back at me, “If you bring water or anything, I will arrest you for molesting.”

I was as shocked at his using the word molesting as he was at my approach to him, and I said, “Molesting? If giving human beings something to eat when they are hungry is molesting, then mothers molest the babes in the crib.” I turned to walk across the street and I heard a white man in the crowd say, “Git 'em!” White people were running toward two blacks who were being beaten by officers. I saw the officers handcuff the blacks and push them into a waiting bus. Then a tall white man went into the bus and cursed the two black youths loudly and shook his finger in their faces. The youths had brought all this on by trying to give an old man a sandwich and a drink of water. The white man who left the bus walked slowly down the street observing every person in line. Later I heard that he was Mr. Dunn, co-owner of the Dunn Rest Home.

The hundreds of people in line included teachers, ministers, professionals, and businessmen and women, as well as domestic workers and housewives. There were also two nurses' aides, who worked at the Dunn Rest Home; their names were Elnora Collins and Annie Cooper. As Dunn passed them, he paused long enough to be sure these were his employees. Mrs. Cooper then said to Mrs. Collins: “There goes Dunn,” and Mrs. Collins replied, “And there goes our job.”

The following day was Mrs. Cooper's day off, but the secretary of the Dunn Rest Home called her to say her services were no longer needed. She had expected this.

That night, the 40 or more employees of the rest home called a meeting and asked me to attend. They decided to ask for the return of Mrs. Cooper or they would all leave. In the petition they drew up, there were other grievances, including need for a raise in salary (they were paid only $16 a week), work hours to be cut from 12 per day to eight, and provisions for sick leave and insurance. The petition was typed, signed, and given to one of the nurses, who was spokesman for the group. The time to hand Dunn the petition was to be 10 o'clock the next morning. Meantime, Dunn sent for Mrs. Collins to come to his office. She also was expecting the call, and went to receive her dismissal for trying to register to vote.

Dunn gruffly announced as she walked in, “Elnora, you're fired. I don't need you around here any longer.”

Elnora smiled and said, “Thank you, Mr. Dunn.” (His employees respectfully addressed him as “doctor,” although he had no M.D. degree.) She left to inform the others, but before she could get to the other workers, Dunn's secretary again called her and told her that Dunn wanted to see her again.

She found him standing in front of his desk with a camera. He told her to face him so he could get a good picture. She knew this was the method used by whites to keep the African-Americans from being hired by anyone else, and she held her purse up to her face and said, “I'm not going to let you take my picture, because I know just what you're going to do with it.” Dunn then put the camera down and picked up a cattle prod he had used on one of the janitors. Before Mrs. Collins could get away he beat her over the head, across the shoulders and on her back, electrifying her entire body and inflicting painful bruises.

She ran screaming out of the office, down the stairs, and into the street. Her alarm brought the rest of the workers from their posts and all left the rest home. The woman who was to deliver the petition remembered it just in time and handed it to the secretary as she passed her in the hall.

This all happened early in the morning, and at about 7:30 a.m., there were 40 nurses who came to my house to tell me what happened. My first impulse was to take Mrs. Collins to a doctor and have the entire group go with us. We did this, and Mrs. Collins was treated for burns and bruises. The Justice Department and the FBI were notified and many sworn statements were taken by them.

What happened to Dunn, superintendent and part-owner of the Dunn Rest Home? The same thing that happened to all white people who mistreated African-Americans. Nothing, except a pat on the back from other racists.

(Note: By late 1967, Mr. Dunn had passed to his reward and the Dunn Rest Home had become integrated.)

Backlash and Frontlash

|

|||

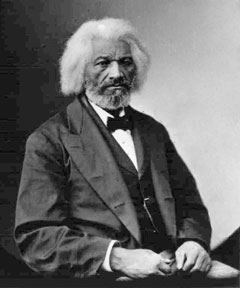

‘The great Civil War-era leader, and friend of President Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglas |

|||

Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground, they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.

—Frederick Douglass

During this time, when the blacks began the struggle to register and vote, there were more than 550 out of jobs, fired because of their participation in some phase of the civil rights movement. No one would hire them, and many were heads of families. This created a grave problem, with the families hungry and half-naked, bills long overdue, and eviction threatening.

A plea was sent out across the nation by SNCC, asking for food and clothing for those who were feeling the backlash from the Selma movement. Other sections of the Black Belt were experiencing the same fate, as their attempts to register brought on white retaliation. Food, medicine, clothing, and other supplies began to pour in.

Many blacks in the middle class as well as others, who steered clear of the movement for fear of the whites, realized they could no longer walk on the other side of the street to avoid those involved. This was the struggle of every black man, woman, and child, and they began to join the others, swelling the mass meetings to overflowing.

Songs and poems were written to be used in the mass meetings. Sharon and Germaine Platts, 12 and 14 years old, respectively, and Arlene Ezell, 14, wrote the following song.

Chorus:

Freedom is a-coming and it won't be long

Freedom is a-coming and we're marching on

If you want to be free, come and go with me.

1.

We are marching on to freedom land

So come along and join, hand in hand

Striving on and singing a song

I hope we're not alone.

2.

We are striving for our equal rights

So come on and join hands and fight

Striving on and singing a song

I know we're not alone.

It was heartwarming to have the doors of the churches open to us, although the ministers were still uncommitted, in spite of the pleas of their deacons and other church leaders for them to take an active part. The grassroots people we were most concerned about showed their profound interest and were determined to work with us. At the opening of the meetings they threw themselves into singing, “We are climbing Jacob's ladder ... Soldiers of the Cross.... Every rung goes higher, higher, Soldiers of the Cross.”

This made the most faint-hearted and discouraged feel the reality of the struggle, and the progress being made for white and black alike. Every round of it moved them higher into the realm of first-class citizenship. They knew that God was with them and they could feel the slackening of the mental chains of slavery that had bound the race for hundreds of years. They could feel freedom overcoming lawlessness, ill-treatment, disenfranchisement, poor housing, unfair employment practices, segregated schools, and many other evils.

One evening my tears flowed freely as I looked into the faces of these people, who believed that freedom was coming. I said to myself: If only the white citizens of Selma would come and see the faces of the new blacks, and hear them lift their voices to God in song and prayer, praying for their white brothers as well as themselves, one would think they would have a change of heart and would realize that, as the black man progresses, so will the white.

But this was no time for tears. We had a job to do and it had to be done now. We had to find jobs for the fired people and give them something besides words of consolation.

I called the Employment Bureau of Alabama to let them know that we were sending women for employment, but they were given the brushoff. Some were told they had to be high school graduates and, when they produced their diplomas, they were given a card to hold until they were called, which of course never happened. This was because when they filled out the information sheets, they had to tell about their local activities, including meetings they attended. They had been dismissed because they dared to break the traditional pattern of the Southern way of life. They wanted to register and vote! They wanted a fair share of America because they had worked for it, and so had their forefathers.

I asked myself, what could we do for the people right away?

For more than 30 years, my sister Elizabeth Smith and her family, who lived in Philadelphia, had operated a small factory in their basement. The large clothing factories kept them supplied with thousands of garments each week. The rough work was done on them and returned to the factory for finishing. Many of the operators they employed were people fresh from the South and others who could not find work elsewhere. Some were given work to take home, but most worked eight hours a day and made as much as $80 a week. If this plan could work in Philadelphia, why not in Selma?

Mrs. Marie Foster and I called together other friends who were willing to give time, and the idea took hold. We realized that help and encouragement had to come from outside the city, because the white citizens who sympathized were afraid of becoming outcasts. Mrs. Ruth Lindsey, Mrs. Geneva Martin, Miss Idell Rawls, Mrs. Foster, Mrs. Gloria Maddox, and I set the project in motion when we brought the plan before the Dallas County Voters League and asked for sewing machines. The First Baptist Church offered its basement and its minister, the Reverend M.C. Cleveland, who was one of the most liberal and cooperative ministers of the larger black churches, offered whatever services he could give. The Reverend Ralph Smeltzer of the Church of the Brethren began to make contacts for us. He made provision for Mrs. Martin and Miss Rawls to go to Maryland for a training course that would teach them to train others. Other white friends sent sewing machines. Applications for working in the project came in by the hundreds from people who were happy to get the chance. They were able-bodied people, who wanted to retain their dignity and self-respect as well as to be independent.

As we began to make progress in training women to sew on high-powered and ordinary machines, the good white people of Selma permitted the sheriff to use any conceivable means to block gatherings of African-Americans, and to hinder the training sessions with the aim of cutting off their power to help themselves.

Governor Wallace had instituted a peculiar kind of government that took upon itself the assignment of penetrating into the North and demonstrating his racist methods. As a result, an organization was formed in Baltimore called GROW (Get Rid of Wallace), that wanted to tell the truth about the principles for which this man stood. I received a letter from GROW asking me to come to Baltimore to challenge Wallace and his hate campaign.

Five rallies were held in Baltimore on Sunday, May 10, 1964. I spoke at all of them and later at Johns Hopkins University, and found the students and faculty in sympathy with the blacks of Dallas County. Many wanted to come down and demonstrate or do whatever they could to break the back of hate-filled segregation. Many felt that if something were not done to discourage this man, even the people who disagreed with his approach would, through apathy, leave the field to him and allow little Wallaces and little Hitlers to flourish all over the country. - An Injunction -

When I came back to Selma, I received an injunction from Sheriff Jim Clark. I had thought he was satisfied because I did not win the Congressional seat and would let me alone for awhile, but not so. He was determined to kill whatever encouragement the blacks might have. His letter forbade us to congregate or have any walk-ins, sit-ins, or any other form of demonstration. “It cannot be,” I thought, and rushed to my office, which was also that of SNCC. “Read this ridiculous injunction,” I said. “I really cannot believe what I'm reading.” Several gathered around and we began to read almost in concert:

WRIT OF INJUNCTION

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF DALLAS COUNTY,

STATE OF ALABAMA

COUNTY OF DALLAS

TO ANY SHERIFF OF THE STATE OF ALABAMA, GREETINGS:

You are hereby commanded, that without delay you execute this writ, and make due return how you have executed the same, according to the law.

Witness my hand this 11th day of July A.D. 1964

To: Martin Luther King, Jr., James Bevel, Amelia Boynton, Marie Foster, L.L. Anderson....

We continued to read through more than 20 names of persons and organizations, which ended with “John Doe and Richard Roe, whose correct names are unknown to the Complainants at this time, but who are described as persons who have or may act in concert or participation with the named respondents, whose correct names will be inserted by amendment when ascertained.”

After we read the list, which included some people who had nothing to do with the movement, we almost pulled the complaint apart, trying to get down to the substance of it. Buried in much legal language was the statement that the gathering of three people or more seen in any public place, including the streets of Selma or anywhere, could be considered in violation of this injunction and therefore would be subject to arrest and jailing by the sheriff of Dallas County.

We looked at each other in amazement. This meant that if the sheriff cared to arrest violators, he certainly would have to arrest the minister (the injunction included all the African-American ministers of churches in Selma and some of the rest of the county), if he had more than one person in his congregation at worship; the teacher if she had more than one pupil; and even worse, if a parent took her family to town to do some shopping, she and her brood could be arrested. We felt that this injunction must be broken and the sheriff's orders challenged.

In the face of Clark's injunction, older African-American citizens began to realize the importance of coming to mass meetings. They would go to the registrar's office and the registrar would fail to pass them. As soon as the waiting period was over, they would go back again. This process went on for several months before the nation realized the African-Americans' plight. Educators, business and professional people, lettered and unlettered, learned and unlearned African-Americans, all went to the board to be given an oral examination by a white person with not more than an eighth-grade education himself, but who happened to be white and perhaps rich.

One African-American teacher, who had earned her master's degree from a Northern college, went to the board several times trying to register. A question was read which she didn't understand, and she asked the man to repeat it. He made another attempt to pronounce the big words, and the teacher said, “Those words are 'constitutionality' and 'interrogatory.' ” The registrar turned red with anger, but realized she was right. He swallowed his pride and continued reading. Though she knew more about government than he would ever know, she flunked the test and was refused her registration certificate.

Another woman I knew tried to take the test many times and failed. The registrar read a half-page to her and then told her to leave the room and stand outside. She was there for more than fifteen minutes. Not knowing what to do, she was about to leave when the door opened and the man called her back. He then told her to write what he had read to her before she left the room. The frustrated woman burst into tears and ran out. So many incredible experiences have been told by the African-Americans who tried to register that if even half are true, they betray only a ridiculous fear on the part of the whites, rather than exposure of unfitness to vote on the part of the African-Americans.

Twice a month the questionnaires were changed. The registrars themselves didn't know the answers, couldn't read the questions half the time, and certainly couldn't interpret them. Applicants could not see the questions beforehand. There was no possible way for either white or black applicants to pass the test, though many whites did get the list in advance. (I was told by a white friend that she was sent a book of questions to study to prepare for registration. I also found that whites visited the courthouse on a different schedule—after hours. Of course, there were not too many whites who needed to register at all, having been voters for years already.)

Even the mastermind of the questionnaire, Governor Wallace, could never pass such an examination. These and other barriers were raised to keep the African-Americans from becoming first-class citizens, and these were some of the reasons the African-Americans had to fight, with demonstrations, confrontations, sit-ins, stand-ins, and walk-ins, which led to the historic 50-mile march from Selma to Montgomery on March 21, 1965. But before that, two other attempts were made to march and much blood was spilled.

In December 1964, we laid plans for a mammoth mass meeting to be held in January, with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as the main speaker. This planning session of Selma and Dallas County leaders opened new avenues and gave great hope to a people which had lost the battle in their struggle to vote. Thus the curtain fell on 1964, and would rise again on a cast which had gained courage and determination. The stars were the weary and worn citizens, leaders, and Dr. King.

The Struggle Goes On

Nonviolence is the first article of my faith. It is also the last article of my creed.

—Mahatma Gandhi

Having one's office across from a Southern jail for 30 years has quite an effect upon one who is in sympathy with the downtrodden. I could hear cries and pleas of prisoners, and often the sound of straps which lashed their bare backs. Many times I closed the door to keep from hearing the weeping of grown men and women. Brutality and injustice we lived with, every day. The very law and order represented by the enforcement officers was such a travesty that it was no wonder the black man was filled with fear when he saw a white man. Day after day, there were black people who feared meeting an officer on the street, because he might suddenly begin beating, kicking, or clubbing him unmercifully, seemingly without cause. This had happened in front of my office many times, and especially because the liquor store was in the same block.

In spite of the atrocities the African-American had to endure, there were many, for a wonder, who had no hate or malice in their hearts—fear and ignorance, but not hate. They wanted only to know where to turn for help, so when Dr. King came into the city, along with SNCC and others, to help unshackle those in bondage, he was welcomed by all blacks of Dallas County. Most of the prisoners and the people who had been to jail for some slight provocation made up their minds that this time they would go for something important—their rights which had been taken away. This explains why the marches and demonstrations were so successful.

After Jan. 2, 1965, when Dr. King came into the picture to work with us, ministers seemed to gain courage and began stepping over each other to get to the rostrum and before the audience. Cooperation improved all around, whereas previously too many were afraid of what the white citizens might think and the effect such activity might have on their credit. A few women, two of them teachers, had to bear the burden until the program mushroomed into a national movement. As the nation was made aware of the denial of civil rights, human rights, and rights of any description for the African-American in Alabama, the same problem came to light in all parts of the country.

On Jan. 18, several hundred people, mostly African-Americans, left Brown's Chapel AME Church on Sylvan Street in Selma and, led by Dr. King, marched to the Dallas County Courthouse. En route we were advised by Safety Director Wilson Baker and his assistants to break up into small groups to keep from violating an ordinance and we took their advice. The march opened a new campaign to get the blacks to make the attempt to register and vote, even though they knew this was only a beginning and would be a dangerous undertaking. How dangerous and how much bloodshed would ensue, we did not know.

Dr. King had registered in the Albert Hotel in Selma, one of the old landmarks, built with slave labor more than 100 years before. The hotel was designed as a replica of the Doge's Palace in Venice. While there, Dr. King was kicked and punched by a white man, who was led away by his comrades.

There followed at least seven weeks of jailings, beatings, starvings, and even killings in early 1965. More than 2,000 men, women, and children were imprisoned in Selma and adjacent counties. In the county jails and prison camps the treatment was deplorable. Meals at the camp consisted of cornbread with sand and rocks in it, syrup, and coffee with salt. There were no toilets, only one open stool; the women had to form a wall around it to keep from being exposed. At the time one group was taken to the camp, there were so many people that they could not stretch out on the floor (there were no beds). The guards made the men stand in single file, each person's nose in the hair of the one before him. If anyone moved, the guard struck him in his privates with a cattle prod. The women had to sleep on a floor that was wet. Such evil treatment was similar to that ordered by Hitler.

The blacks stopped buying from downtown, and business fell off more than 50 percent. This set off a chain of resentment from the local white men, but they did not have the power to stop Sheriff Clark and his intimidations. Everyone coming into my office inquiring about him wanted to know, “What manner of man is this, that all white people in the city seem to fear him?” He typified the great power of the sheriff in the South.

One woman had told her daughter to “stay out of that mess, because my white folks told me I would lose my job if my family got involved.” She had sent her daughter to the store and on the way, with no provocation, an officer arrested her. After this, the mother told me she was going to fight to the finish, and take part in every demonstration, even if it meant her job. My consolation to her was that she was in it when she was born an African-American.

Several students from Selma University were arrested for demonstrating along with hundreds of others. The president of the university bargained with Clark to let him have the students back, and promised that they would not be further involved. These students were pressured in every way by the president. This did not go so well with other students, whose parents had also been denied the right to register and vote.

A group of other students demonstrated in front of the courthouse and were joined by others of all ages. Clark proceeded to march them back past their headquarters, Brown Chapel AME Church. He told them to keep moving, and when they got out of the residential section, he sat on the hood of his car and, with a cattle prod, shocked everyone he could reach. They were driven three miles out in the country, and they tried to run. He had his driver speed up and he kept sticking them as they tried to run out of his way. Many fell to the ground, exhausted, and a few ran behind trees and under houses. After Jim Clark did all the damage he could without killing anyone, he rode back to the city and left the students to get back the best way they could.

The second and fourth Tuesdays of each month were days when those who wished to vote in coming elections could register. In addition, a solid week was set aside for registration. Hours that the books were supposed to be open at the county courthouse were 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., during most people's working hours, of course. Many African-Americans would go at 6 o'clock in the morning and stand in line in order to register. Sometimes they stood all day and the books would not be opened. It was obvious that all officials and other white people would do everything that they could think of to discourage blacks from becoming first-class citizens. Those were dark days for us.

Having been a voter since the 1930s, my part in the proceedings, along with several other already registered voters, was to act as a voucher. We had to know the registrant, swear before the registrar that we knew him to be who he said he was, confirm his age, his place of residence, and the length of time he had lived there. He then filled out a preliminary form with these and other statistics. After that, he had to pass both oral and written tests.

Black people, as previously mentioned, were not allowed to come through the front door and later, not even through the side door; they were told to go into the courtyard and stand. The courtyard had no seats; it was just a big open space, paved for the convenience of the whites, who had to walk from one building to the other, and for the cars of employees. It mattered not how old or crippled a potential registrant was, he had to stand and hear the abuse of Jim Clark and his deputies. I heard one say, “Damn bunch of black buzzards. I'm tired of lookin' at 'em. Who the hell they think they are? I'd close up the whole damn place and make 'em go home.” Even when it was raining, instead of allowing them to go through the building to stand in the courtyard, or better still, in the hall, the deputies made them march around the block and back into the courtyard to stand in the rain. - 'Lord Have Mercy on America' -

An old gentleman asked me to vouch for him one day, and when the registrar handed him the book to sign, he began to write his name with trembling hands. The registrar watched coldly, then said, “Old man, don't you see you are crossing that line? What's wrong with you?” Trembling, the old man tried to stay on the line as he finished writing his name. The registrar then said, “You haven't finished; now write your address.”

The man said, looking at me, “Mrs. Boynton will write it for me; I can't write so good.”

Again the registrar raised his voice: “You can't write your address, you've failed already. You might just as well get out of the line.”

At this point I opened my mouth to say something, but I could never have said anything as well as the few words uttered by the prospective registrant. He stood erect, looked into the eyes of the registrar and said, very clearly and fearlessly: “Mr. Adkins, I am 65 years old, I own 100 acres of land that is paid for, I am a taxpayer and I have six children. All of them is teachin', workin' for the government, got they own business, and preachin'. If what I done ain't enough to be a registered voter wid all the tax I got to pay, then Lord have mercy on America.”

I was very proud of this man, who had won his case, for the registrar then gave him the long list of professional questions to be answered (not that he or anyone else could pass the tests).

The next day I went back to wait for other prospective voters who might need a voucher. I was in the center of the hall, and an officer told me to move. I moved back several paces, and in a few minutes another officer told me to move to the yard. Of course there was no way for a person who needed me to see me there, but I wanted to avoid any appearance of insubordination. I was in the yard only a short time when Sheriff Clark came to order me back into the hall. On the way, I told the deputy I was sent back by the sheriff, but the deputy said I was still in the way. It was nearly noon, so I went to the end of the hall and sat on one of the chairs placed there purposely for persons waiting to see the probate judge.

In another few minutes a white man walked up and said, “Git up and git the hell out of here.” I told him I was there for a purpose.

In a threatening manner he said, “You aren't going to move?”

I said calmly, “No.” He wheeled around as though he were going to get an officer to throw me out. I waited a few more minutes to see what he was really going to do, but he didn't come back and I went out to lunch.

After lunch, I went back and picked up a newspaper, pretending to be absorbed in it, though in reality I was watching the movements of the people in line. Pretty soon the probate judge confronted me, saying, “Amelia, get right up and move from here. You are disturbing my court.”

I said, “I did not know you were having court.” I had not heard conversations or seen anyone enter his office.

He only said, “I said get up and move and I mean now.” I told him I was sent to this seat by the deputy and he quickly retorted, “This is my court, and I am the one to give orders here.” I got up and stood until 4:30 that afternoon.

No black person successfully completed registration that day; none even got so far as the office to be processed. The next day an even larger number of blacks came, and this time I entered the hall from the front door without being stopped. There was a long line from the door of the registrar's office, down the hall, and into the alley. It was miserably cold and the sun was not shining to help warm the faithful army. Again I stood in the hall.

I had parked my car at a parking meter, and when I figured the time had expired, I left by the front door to put in another dime. Coming back, I met Sheriff Clark at the front door and he said, “Where are you going?” I explained I was going to wait for those who needed a voucher. He sent me to the side door, where I encountered a wall of sheriffs with their guns drawn. I started to pass through, and one of them said, “You can't come through here.” I told them I was a voucher and I was to stand just inside the door back of them. I waited in front of this human wall while one of the deputies went to the front and asked Clark about me. He came back to say, “You can go in. Go down the street around the block and come up from the back.” The distance was more than a block, but I did as I was told, ending up a few feet from where I had been ordered away.

At noon, everybody left for lunch and I too left to go to my office. As I passed the front of the courthouse, I saw about 60 blacks lined up against the building with the sheriff looking down on them from the steps. This group, I later learned, had been singled out of the line in the back for talking or stepping out of line or some other insane reason, and were being disciplined. Most of them had voiced objections to having to go around the block and stand in the back alley instead of entering the front door of the courthouse. Clark had a big club in his hand and he noticed me coming down the street. He yelled to me, “Where are you going?” I said I was on my way to my office. He said, “Oh no, you aren't. You are going to get in this line.” Again I told him I had to go to my office and again he told me to get into the line against the wall. Before I could gather my wits, he had left the steps and jumped behind me, grabbed me by my coat, propelled me around and started shoving me down the street.

I was stunned. I saw cameramen and newspaper reporters around and, knowing how Clark liked publicity, I said, “I hope the newspapers see you acting this role.”

He said, “Dammit, I hope they do.”

The African-Americans standing in line were indignant, but the only consolation they could give me was, “Go on to jail, Mrs. Boynton, you'll not be alone. We will be with you.” What more consolation would one need? With a final grand push, the sheriff shoved me into a deputy's car and said, “Arrest her and put her in jail.”

As I entered the county jail on the third floor of the city hall, my purse was searched and taken away from me, I was fingerprinted five different times, photographed, and given a criminal number across my chest. I was then brutally handled, pushed down the hall, and thrown into a jail cell. Later, from the cell, I heard the group, who had cheered me on at the courthouse. They had been marched the three blocks to the jail, singing, “Oh freedom, oh freedom, oh freedom over me. And before I'll be a slave, I'll be buried in my grave, and go home to my Lord and be free.” This song had never sounded so sweet to me as when they stood before the barred door that led to the jail itself and began to sing again.

The jailer tried to open the door but the lock jammed. When the janitor's keys couldn't open the iron doors, the locksmith was called. He too tried and failed. Finally, he informed the jailers that he would have to go back to his office and get an acetylene torch, to burn off the hinges or locks. For nearly an hour, the African-Americans stood and sang and repeated Bible verses and interpreted Scripture to those nearby. “Oh yes,” said one freedom fighter, “when God closes a door no man can open it, and God closed that door.” Finally the jailer gave orders to have the 60 blacks go back downstairs and come up on the elevator.

At 2:30 that afternoon, I was taken back to the courthouse for an arraignment. When we entered the courtroom, there was no judge, and he never did come. So back to jail I went, to remain until some sort of trial could be set, and some kind of charge brought against me.

That night, another court was held and all the group was taken to the courthouse again and charged with unlawful assembly. I was the last person to be arraigned, and I was charged with criminal provocation. The irony was that Sheriff Clark had done a criminal act when he arrested me, and the mere fact that I was walking as a free citizen was what provoked him. But of course, the court was not interested in the facts; I was “inciting” blacks to be citizens and that was crime enough. For “criminal provocation,” my bond was set higher than the others.

I got home about 10 o'clock that night with my “diploma”—the charge of criminal provocation—and I wondered why I had not made a greater contribution to being arrested. I had missed my club meeting down the street. Although it was late, one of my friends came to the house and told me that the entire meeting was centered around the illegality of the sheriff's act and what they could do about it. All the club members were teachers, but at this arrest they lost fear of losing their jobs and made plans to call on all the teachers to demonstrate in a body against the brutal treatment and the mass arrests. Most of the teachers were not registered voters, though they had tried many times.

The next day I went to Birmingham, where my attorney filed a court order against Sheriff Clark, which would set aside his order of “unlawful assembly” of African-Americans in Dallas County. I told my attorneys that I had to get back to Selma Friday, Jan. 22, by 2:30 in the afternoon, because the teachers were going to march on the courthouse. The lawyers laughed and said I was wasting time thinking the teachers were going to stick together.

I got back in time to join the teachers, who were led in their march by the president of the Dallas County Teachers Association, the Reverend Frederick D. Reese. Of about 135 teachers, only three were absent from the demonstration. They stood on the steps facing Sheriff Clark and a spokesman said they wanted to go to the registrar's office. The sheriff stood in front of the group with his cattle prod, and began to push the teachers off the steps. But this did not keep them from continuing to try to get through. They were repulsed each time by the line of officers. Deputies who had hardly an eighth-grade education called them filthy names and made insulting remarks. The teachers did not succeed in reaching the registrar's office, but before leaving the courthouse, they let the sheriff, the deputies, and the other whites know that they were not afraid and that they had joined the battle for freedom.

Bloody Sunday

Nonviolence and truth are inseparable and presuppose one another. There is no god higher than truth.

—Mahatma Gandhi

On Feb. 1, 1965, Dr. King was arrested in Selma and lodged in the county jail for leading the Jan. 18 demonstration. This aroused people in all walks of life all over the country. They began to come to Selma to offer their services in whatever way was needed. The Reverend Andrew Young, Dr. King's aide, announced at a night meeting that a group of people from Washington, D.C., including Congressmen, would visit Selma unofficially.

I was to drive to the Montgomery airport and lead the group back to Selma. The Congressmen would ask at city hall to see Dr. King. I was to sign his bond, and the entire group would come to my house for a meeting. I met the plane and found the 15 Congressmen, eight other friends, and a host of newsmen.

The whole group of about 50 persons tried to enter the side door of City Hall, but it was locked. I thought the front door would be open, but found that locked also, so we went to the prisoners' entrance, which was open. The day was cold and dismal with a drizzle of rain. The only bright spot of the day was the spirit of the Congressmen.

The hall was clear of people, except for one man, Mayor Joe Smitherman, who stood behind the entrance door with his hand on the doorknob. “Don't let them come in here,” he said. He was a tall, frightened, unsteady, thin man—the Mayor for one month of Selma, Alabama, a city of about 29,000. “Don't let them come in here,” he said again. Although all of the group was still outside the building except Congressman John Dow of New York, who was close behind me and halfway in the door, the Mayor began to recite his canned speech.

“I am the Mayor of the City of Selma,” he began.

I knew he meant to be heard, so I said, “Mayor, these people cannot hear you. They will have to come in if you are talking to them.”

He took several steps backward, with both hands held up as though he were pushing something away from him, then said, “Well, let them come right in here” (motioning toward the small hall), “but don't let the newsmen in.”

The door was open now and the Congressmen began to file into the hall, so it was natural that all the others would follow. The Mayor was determined to get his speech out, so he started again. “I am the Mayor of Selma and we have been getting along all right until outsiders came in. We don't need any outsiders.”

At this point, Congressman William Fitts Ryan of New York and others said, “We want to see Dr. King.”

The Mayor said, “Gentlemen, you cannot see King unless you get him out on bond.”

One of the other Congressmen answered, “We don't want to get him out. We just want to see him.”

“Well, you just can't see him.” The Mayor was still nervous and did not realize that the worst was yet to come.

When all the Congressmen had entered the hall and the Mayor gradually backed into the larger hall, one of the Congressmen asked, “Why do you bar blacks from registering and voting?” Another asked about the discriminating pattern practiced and another about the inhuman treatment of the demonstrators. The Mayor, having nothing to do with these atrocities, tried very hard to answer these questions, but often found himself getting so entangled with the lawmakers of the nation that it was embarrassing.

Just then the city and county attorney came among the group and said, “Mayor, you don't have to answer their questions.” But the attorney went away, leaving the Mayor to continue the struggle. Later the attorney returned and took him by the elbow, as one would a child in trouble, and steered him away while he was yet talking, leaving the Congressmen and the others, including newsmen, standing there amazed.

The spell was broken when Selma's safety director, Captain Wilson Baker, came and announced that Dr. King had been released. He was slipped through the front doors while the Mayor was floundering with his hangups. When the group reached my house on Lapsley Street, Dr. King was there awaiting us. Included in the conference, together with some of the local black leaders and SCLC people, were the following Congressmen: Jonathan B. Bingham, James H. Scheuer, Ogden R. Reid, William Fitts Ryan, and Joseph Y. Resnick, and John Dow, all of New York; Jeffrey Cohelan, Kenneth W. Dyal, Augustus F. Hawkins, and Don Edwards, California; Weston E. Vivian and Charles Mathias, Maryland; and John Conyers, Jr., Michigan. The son of Adam Clayton Powell of New York was there and others who represented still other Congressmen.

Dr. King, the SCLC representatives, and I answered questions about what was going on in Selma, information that the Congressmen could take back to Washington. The various Congressmen later scattered and visited with other people, white and black, for further details. This groundwork led to their drafting of a right-to-vote bill, ratified by Congress the following August.

But in the meantime, all was not well in Selma and surrounding counties for those who tried to register. Blacks were being beaten, jailed, and made to walk for miles in biting cold weather after being released from prison. Jimmy Lee Jackson of Marion, 30 miles from Selma, Alabama, had been shot to death by one of Governor Wallace's state troopers after a mass meeting. The officers had gone into the church and ordered the people to disperse. The people left peacefully, but they were hounded and harassed. A trooper followed Jimmy Lee and his mother into a neighboring cafe and began to beat the woman. Jimmy Lee, who stayed with her, was killed in cold blood.

I can never do justice to the great feeling of amazement and encouragement I felt when, perhaps for the first time in American history, white citizens of a Southern state banded together to come to Selma and show their indignation about the injustices against the African-Americans. On March 6, 1965, seventy-two concerned white citizens of Alabama came to Selma in protest. They had everything to lose, while we, the African-Americans, who were deprived and on the bottom rung of the salary scale, had nothing to lose and everything to gain.

The white group included business and professional men and women, ministers and laymen. Before they came they asked to use one of the public buildings for assembly and were refused. The white churches were afraid to open their doors to them and finally they gathered in a black church, the Reformed Presbyterian. A plan was worked out to keep any of them from coming in bodily contact with the law.

The Reverend Joseph Ellwanger, pastor of an integrated Lutheran congregation in Birmingham, was the group's spokesman. (He was the son of Dr. Walter H. Ellwanger of Selma, president of the Alabama Lutheran Academy and College for twenty years). Two by two these people marched to the courthouse. As they assembled, other people were already gathered, the whites to jeer and the blacks to cheer. While the Concerned White Citizens of Alabama (CWCA) sang “My Country, 'Tis of Thee,” a group of white hecklers began to scream, yell, and whistle. Even when the minister offered prayers, they showed all kinds of disrespect. The CWCA ignored their irreverence and prayed for them.

During Pastor Ellwanger's reading of the “Purpose of the Concerned Citizens,” a gang of white men raced down the street in an old car with no exhaust pipe. The noise was horrendous. Suddenly, the car stopped in front of the minister and the gang yelled at him. One of the men held up the hood of the car from which came some type of chemical, which made a smoke screen and gave off a repellent odor. The sheriff, who, with his deputies, was surrounding the CWCA, paid no attention to them, but neither did the CWCA people. The annoying group finally left.

With all our conferences, pleadings, confrontations, and demonstrations, the registration board and the Black-Belt officials were determined to beat the African-Americans down physically and mentally. Every time the African-Americans came back up, fighting nonviolently. - Selma to Montgomery -

We knew that the crux of the trouble in Alabama lay in our Governor, George Wallace, and we decided to march the 50 miles to the state capital and hand our grievances to him. The march would begin the next day, Sunday, March 7, 1965.

The city knew of our plans for the march, but did not know how to stop it. Meetings were held day and night to map out strategy by which we could appeal to the conscience of the diehards. People had begun to come in from all over the country to lend assistance in the registration and voting drive. The county board of registrars refused to permit African-Americans to vote, the county officials kicked them about for asking to register, the Governor of the state gave them mountains of legal questions that were impossible to answer, and the Congress in Washington was still filibustering and allowing the Southern bigots to twist their arms. We were left no alternative but to walk 50 miles to the capital, not to ask, not to plead, but to demand the right to register and vote.

The night before the march, we gathered at the church and talked with the citizens, asking them to walk with us regardless of the cost, even if it meant “your life.” I was afraid of being killed, and I said to myself, “I cannot pay the supreme price, because I have given too much already.” But I also then thought, “Other mothers have given their lives for less in this struggle and I am determined to go through with it even if it does cost my life.” At that moment, a heavy burden fell from my mind and I was ready to suffer if need be.

|

||||

| President Lyndon B. Johnson received Amelia Robinson at the White House, following the signing of the Voting Rights Act, on Aug. 7, 1965, after a long hard struggle. |

||||

As we passed a line of well-wishers and little tots who wished they could join the group, a woman said to me, “Honey, I can't walk but I sure will pray for you all.” Another said, “Thank God He done sent His disciples to help us.” Still another said, “I prayed so hard for you all. It might be stormy but God will bring you through!” All of these sayings I kept in my heart, and I too uttered a prayer to be saved from the evil to come.

As we left the church, we saw scores of officers of the city, and county and state troopers huddled in groups, smiling and looking somewhat human. I did not have a hat but was otherwise prepared for the cold weather. My friend Margaret Moore said, “Here is my raincap, put it on. You'll be needing it.” Then Marie Foster and I fell in line third from the front.

We marched from Brown's Chapel AME Church in the black section toward town. The officers had us close ranks and walk faster and by larger groups. This was different from previous marches, where we had to walk two by two, and 10 feet apart, regardless of our large numbers.

The marchers were accompanied by portable latrines, first-aid buses, water, and food. Like the children of Israel leaving Egypt, we marched toward the Red Sea, and we were on our way, not knowing what was before us.

As we approached the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which spans the Alabama River, we saw the sheriff, his posse, deputies, and men plucked out of the fields and stills to help “keep the 'niggers' in their place.” As we crossed the bridge, I saw in front of us a solid wall of state troopers, standing shoulder to shoulder. I said to Marie, “Those men are standing so close together an ant would get mashed to death if it crawled between them. They are as lifeless as wooden soldiers.” Marie pointed to the troopers on the sides of our marching lines and said, “It doesn't take all of them to escort us.” But a second look convinced us that trouble was brewing for the nearly 1,000 marchers.

Each officer was equipped with cans of gas, guns, sticks, or cattle prods, as well as his regular paraphernalia. Beyond them, men on horses sat at attention. I remembered the words of a little girl, who wanted to go with us because she wanted to be free, and prayers that were being offered on our behalf, and the old lady who said she would stay on her knees while we were away. I knew we would need all those prayers as I looked on the faces of these men, who were just waiting for a chance to shed human blood.

Part of the line being across the bridge, we found ourselves less than 50 yards from the human wall. The commander of the troops, on a sound truck, spoke through a bullhorn and commanded us to “stop where you are.” Hosea Williams of SCLC and Cong. John Lewis and all the line behind them halted. Hosea said, “May I say something?”

Major Cloud retorted, “No, you may not. Charge on them, men.”

The troopers, with their gas masks on and gas guns drawn, then began to shoot gas on us and the troopers in front jumped off the trucks. Those standing at attention began to club us. The horses were brought on the scene and were more humane than the troopers; they stepped over the fallen victims.

As I stepped aside from the trooper's club, I felt a blow on my arm that could have injured me permanently had it been on my head. Another blow by a trooper as I was gasping for breath knocked me to the ground and there I lay unconscious. Others told me that my attacker had called to another that he had the “damn leader.” One of them shot tear gas all over me. The plastic rain cap that Margaret Moore gave me may have saved my life; it had slipped down over my face and protected my nose somewhat from the worst of the fumes. Pictures in the paper and those in the possession of the Justice Department show the trooper standing over me with a club. Some of the marchers said to the trooper, “She is dead.” And they were told to drag me to the side of the road.

There were screams, cries, groans, and moans as the people were brutally beaten from the front of the line all the way back to the church—a distance of more than a mile. State troopers and the sheriff and his men beat and clubbed to the ground almost everyone on the march. The cry went out for ambulances to come over the bridge and pick up the wounded and those thought to be dead, but Sheriff Clark dared one of them to cross the bridge. At last a white minister and a black citizen told him, “If you don't let the ambulance over the bridge, these people are going to retaliate by killing some of you and you may be the first one.” The ambulance was then permitted to pick us up. I also heard that I was taken to the church after being given first aid on the way, but when I did not respond, I was taken to the Good Samaritan Hospital.

When I regained consciousness I wondered where I was, but then I remembered the voice through the bullhorn, the gas being shot, and the men with gas masks. From the looks of the other patients around me, Highway 80 across Edmund Pettus Bridge must have had a bloodbath.

Many months after this march, I went to a specialist for throat problems. I was told that my esophagus was permanently seared and scarred by the teargas. One result, besides continuing throat problems, is that it changed my voice from lyric-soprano to mezzo-soprano.

Though it was months before I recovered from the experience, my spirit soared as I realized what it meant to sing and really feel, “Oh freedom, over me; and before I'll be a slave, I'll be buried in my grave, and go home to my Lord and be free.”

Amelia Boynton Robinon’s Autobiography, Bridge Across Jordon

90th Birthday Celebration: "Her Love is a Higher Power"

91st Birthday and Ceremony "Boynton Weekend in Selma, Alabama"

Biography of Amelia Boynton Robinson

Mrs. Robinson’s Dialogue of Cultures Visit to Iran

Program to Mrs. Robinson’s Play, “Through the Years”

What is the Schiller Institute?

Lyndon and Helga LaRouche Dialogues, 2004

Writings of Other Great Thinkers

![]()

schiller@schillerinstitute.org

The Schiller Institute

PO BOX 20244

Washington, DC 20041-0244

703-297-8368

Thank you for supporting the Schiller Institute. Your membership and contributions enable us to publish FIDELIO Magazine, and to sponsor concerts, conferences, and other activities which represent critical interventions into the policy making and cultural life of the nation and the world.

Contributions and memberships are not tax-deductible.

VISIT THESE OTHER PAGES:

Home | Search | About | Fidelio | Economy | Strategy | Justice | Conferences | Links

LaRouche | Music | Join | Books | Concerts | Highlights | Education | Health

Spanish Pages | Poetry | Dialogue of Cultures | Maps

What's New

© Copyright Schiller Institute, Inc. 2004. All Rights Reserved.