Highlights | Calendar | Music | Books | Concerts | Links | Education | Save DC Hospital

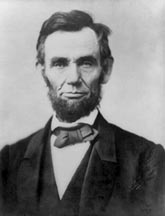

The Lincoln Revolution

by Anton Chaitkin

A Test of Your Mental Independence

Abe Lincoln Stood Up to the Imperial Liars

The Lincoln Revolution Overseas

President Abraham Lincoln: Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865

Reprinted from FIDELIO Magazine, Vol . VII No. 1 , Spring, 1998

Most figures and graphics are not included online.

Click to order this issue or to subscribe.

What was the character of the patriotism, which was activated, impassioned, by the news of Pearl Harbor? The answer is: Abraham Lincoln.

What was the character of the patriotism, which was activated, impassioned, by the news of Pearl Harbor? The answer is: Abraham Lincoln.

In my generation, Abraham Lincoln was patriotism. ...

What Lincoln represented, as President, was the reaffirmation and the consolidation of the original intent of the founders, an intent which is located in the question of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," in opposition to the Lockean principle of greed. And, the idea that every human being is not only made in the image of God, but society must be ordered in a way which conforms to the implications of that, as I've defined them.

Today, that principle is the central issue of all global politics: The fact that the United States, when we were called to service in World War II, went to service with the heritage of Lincoln, and the Union victory in the Civil War. ...

—Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr.

We look to Abraham Lincoln, in a timeof global and national crisis, to inquire into the nature of his leadership, his principles, and his accomplishments. Lincoln saved the United States by reviving and reopening the American Revolution, against its still undefeated enemies on both sides of the Atlantic. He used the occasion of the war for the Union to so profoundly mobilize a fighting people and their production, that the results were truly a revolution—in his words, "fundamental and astounding."

We shall consider here, first, the character of the challenge Lincoln faced as he assumed the Presidency.

Then, in order to comprehend the measures Lincoln adopted, the tradition which he represented must be analyzed. The republican thinking of Lincoln, his nationalist strategists and his "Hamiltonian" predecessors, so contradicts the degraded axioms of the past thirty years, and these nationalists have been so viciously misrepresented, that both Lincoln's admirers and his detractors have consented to view the political struggles of the first century of the United States through worthless party labels, and through ideological constructs manufactured by the cheapest, meanest enemies of America's national existence.

After attempting to blow away some of the smoke obscuring the current view of these earlier contests—in which Lincoln himself became passionately involved long before his Presidency—, we shall see how Lincoln activated the nation's moral and economic resources, outflanked the enemy London-New York banking axis, and transformed the modern world.

I. Terrorism, and Decisive Action

The secession of the southern slave states began in reaction to Abraham Lincoln's November 1860 election, and exploded into a terrifying showdown for national existence before Lincoln was inaugurated on March 4, 1861. Unlike the disastrous sitting President, James Buchanan, Lincoln was committed to stop the spread of slavery into the western territories, and to oppose the pretension of states' "rights" to break up the Union. Lincoln judged the secession movement as the product of traitors who "have been drugging the public mind of their section for more than thirty years."1

As Lincoln made his way eastward toward Washington from his Illinois home in February 1861, insurrectionists were completing the capture of almost all U.S. military forts in the south, along with the southern arsenals, dockyards, customs-houses and courthouses; were plundering the U.S. mint at New Orleans; and were planning to seize the nation's capital at Washington, D.C.

The Chicago Tribune (Lincoln's Republican Party paper), exposing the insurrectionists' determination to block the transfer of the Presidency to Lincoln, reported "Beneath all this talk ... unquestionably lurks a scheme for the assassination of Lincoln and [Vice President-elect Hannibal] Hamlin"2; and quoted the Richmond Enquirer, "[I]f Virginia and Maryland do not adopt measures to prevent Mr. Lincoln's inauguration at Washington, their discretion will be ... a subject of ridicule ... ."3

Through several very reliable channels, including the commanding Army general Winfield Scott, it became known that an attempt would be made to assassinate Lincoln in Maryland, before he reached Washington. It was determined, in connection with the most trusted group of Lincoln's supporters—the "national party" leaders around Philadelphia economist Henry C. Carey—that the President-elect, in disguise, would take an undisclosed train route through the night.

An aide to Lincoln, Col. Alexander K. McClure, describes the departure from Harrisburg, the Pennsylvania capital: "[O]n the night of February 22, 1861, when at a dinner given by Governor [Andrew] Curtin to Mr. Lincoln, then on his way to Washington, we decided, against the protest of Lincoln, that we must change his route to Washington and make the memorable midnight journey to the capital. It was thought to be best that but one man should accompany him, and he was asked to choose. ... He promptly chose [his close friend from Illinois,] Colonel [Ward] Lamon, who accompanied him on his journey from Harrisburg to Philadelphia and thence to Washington. ... Governor Curtin asked Colonel Lamon whether he was armed, and he answered by exhibiting a brace of fine pistols, a huge bowie knife, a black jack, and a pair of brass knuckles. Curtin answered: 'You'll do,' and they were started on their journey after all the telegraph wires had been cut. We awaited through what seemed almost an endless night, until ... [dawn,] when Colonel [Thomas A.] Scott, who had managed the whole scheme, reunited the wires and soon received from Colonel Lamon this dispatch: 'Plums delivered nuts safely.' "4

Ward Lamon, thereafter Lincoln's chief of bodyguards and the Marshal of Washington, years later expressed the harsh reality of what Lincoln confronted: "It is now an acknowledged fact that there never was a moment from the day he crossed the Maryland line, up to the time of his assassination, that he was not in danger of death by violence, and that his life was spared until the night of the fourteenth of April, 1865, only through the ceaseless and watchful care of the guards thrown around him."5

The new President was safely inaugurated March 4, 1861, under very heavy military guard led by Gen. Winfield Scott's artillery and sharpshooters.

The U.S. Fort Sumter, in the harbor at Charleston, South Carolina, surrendered Saturday, April 14, after a brutal bombardment by secessionists.

Up until that time, the North was divided and weak in its resolve. The United States at that moment had less than 12,000 regular army troops, with less than 3,000 available for east coast duty, and a tiny, widely scattered navy. The government was bankrupt, such that even the Congress could not be paid; the treasury had been plundered by pro-secession cabinet officers, while revenues had plunged into deficit from the economic collapse under radical free-trade policies.

With no men, and no money, but as he had pledged to do, President Lincoln acted. The day after Fort Sumter's surrender, April 15, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers, under the authority of an act passed in 1795 by George Washington. There was an immediate, electric response of loyalty and relief from the American people. The thinking was of the type: "I'm a Democrat and voted against Lincoln, but I will stand by my country when assailed."

Troops left Massachusetts on April 17, bound for Washington. As they passed through Baltimore April 19, the tracks were blocked, and the exiting soldiers were attacked by a mob with pistols and rocks. Four soldiers and nine rioters died, and dozens were wounded. The troops finally got through to Washington, and were quartered in the Senate chamber of the Capitol building.

The disloyal city government then disabled the bridges through Baltimore. On April 21, insurrectionists seized the Baltimore telegraph office. Washington was cut off by rail and wire from New York.

Maryland Governor Thomas Hicks wrote to the President, advising that "no more troops be ordered or allowed to pass through Maryland," and proposing that "Lord Lyons," the British Ambassador, "be requested to act as mediator between the contending parties in our country."6

Lincoln later described the situation immediately following the bombardment of Fort Sumter: "[A]ll the roads and avenues to this city were obstructed, and the capital was put into the condition of a siege. The mails in every direction were stopped, and the lines of telegraph were cut off by the insurgents, and military and naval forces which had been called out by the Government for the defense of Washington, were prevented from reaching the city by organized and combined treasonable resistance in the state of Maryland. There was no adequate and effective organization for the public defense. Congress had indefinitely adjourned ... ."7

What to do about the traitors in Maryland? Lincoln wrote to General Scott that the "Maryland legislature assembles to-morrow ... and not improbably will take action to arm the people of that state against the United States." Nevertheless, Lincoln advised against immediate action by the army to "arrest or disperse members of that body" to prevent such action from occurring; but he asked General Scott to "watch and await their action," and then to move "if necessary, to the bombardment of their cities and ... the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus."8

By orders issued April 19 and 27, Lincoln set up a blockade of the southern ports.

In an April 27 order telling Gen. Winfield Scott, "You are engaged in suppressing an insurrection against the laws of the United States," the President authorized the suspension of the right of habeas corpus along the military line from Washington to Philadelphia.9 Insurrectionists could then be arrested and held without trial, at the discretion of the army officers.

Lincoln directed April 30, that all army officers who entered the service before that month must take a new oath of allegiance to the United States.

On May 3, he called for another 42,034 volunteers to serve three years, and for the increase of the regular army by 22,714, and of the navy by 18,000.

Throughout this period, Lincoln acted on his own authority. The Senate had gone out of session March 28, and the House of Representatives was out of session after the inauguration; Congress was not even scheduled to reconvene until December 1861.

But Lincoln called Congress into Special Session beginning July 4, 1861. On that anniversary of American Independence, Lincoln defined the war, and the meaning of America's existence, for his people and the world. We shall return to this Special Session Message in the treatment of the mobilization, below.

Lincoln now asked Congress "that you place at the control of the Government for the work at least 400,000 men and $400,000,000."10 The entire northern population then was only about 20 million; and the sum called for was more than eight times the average yearly revenue of the government in the years 1858 through 1861, while a large part of the nation had just disappeared, fiscally speaking.

The first large-scale battle between U.S. and rebel forces, July 21 at Bull Run in Virginia, resulted in a rout of the government troops.

London Times correspondent Sir William H. Russell exulted. Russell wrote that the U.S. government would be defeated if they "yield to the fanatics, and fight battles against the advice of their officers." He doubted if "the men and the money [would] be forthcoming ... to continue the war of aggression ... against the seceded states."11

And yet, Lincoln was to rally the country to a pitch of morale and productivity such as the world had never seen. Under Lincoln's guidance, a process was set afoot whereby the entire technological character of American industry and agriculture, the power of man over nature, was radically upgraded; and government revenues, wages, profits, and population all expanded dramatically. This continued despite Lincoln's 1865 murder, so that the United States quickly arose, from near national death, to become unquestionably the greatest industrial and military power on earth. The U.S. meanwhile moved to spread this Lincoln Revolution to men of all continents.

II. Lincoln's Nationalist Inheritance

Abraham Lincoln and other Nineteenth-century American nationalists knew that two systems of political-economy contended for world preeminence, their "American System" of protectionism, versus the predatory British Crown and bankers' system of free trade or "laissez faire." American nationalism—the elected government interfering in the economy and market place against the bankers' and cartels' domination—was used to elevate the condition of Americans above that of the helpless, property-less peasants of Europe.

The basic economic controversy in American history has often been wrongly reduced to a set of formulas, and reported accordingly. These are actually half truths, which have become falsehoods as they have been torn violently out of their easily-known historical context:

1. That President George Washington's Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton promoted national government economic intervention, while President Washington's Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, opposed such intervention.

2. That political parties, originally Hamilton's Federalists and Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans, opposed each other along the lines of the Hamilton versus Jefferson controversy (followed later by the protectionist Whigs versus the free-trade Democrats, and then the protectionist Republicans versus the free-trade Democrats).

3. That Jefferson authored the Declaration of Independence, arguing for the rights of man against the British Empire; and Jefferson, as U.S. President, was head of a party which stood up against British aggression, whereas the Federalists allied with the British against American rights.

These formulas are then put in the service of a ridiculous lie, to wit:

4. That Hamiltonian economics—Lincoln's philosophy—interfering against the power of bankers and British lords, to free the people from poverty and slavery, is against human freedom, conceived as "freedom of government interference"!

The final step in this idiocy, is to claim for the economic dogma of Britain's Adam Smith—that our nation must not check the economic power of our foreign enemies, nor deliberately raise our national productive power—that this nationally suicidal dogma is supposedly "American" economics, because Jefferson agreed with it.

This is reenforced by reference to Communism, as stateism; thus, you must oppose government intervention, or risk being labeled a Communist.

But, since Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Abraham Lincoln were neither Communists, nor adherents of Adam Smith, this entire web of falsehood depends for its acceptance on public ignorance of the basic history of the United States.

Let us begin to untangle the web by reviewing a letter Lincoln wrote to a group of Bostonians in 1859.

Lincoln turned down the Bostonians' invitation to their celebration of Jefferson's birthday. These particular Bostonians were ostensibly members of Lincoln's own Republican party, but some or all of them tended toward British free trade.

In praising Jefferson, Lincoln delivered some barbs, for the wealthy Boston families had been the original center of British Tory opposition to the Revolution, and those Boston "Brahmins" were the channel for British empire subversion of American political life. Together with their Anglophile allies in Wall Street and the southern slaveocracy, they were the rotten soul of the pro-free-trade faction.

Lincoln throws a paradox at them:

Your kind note inviting me to attend a Festival in Boston, on the 13th [of April] in honor of the birth-day of Thomas Jefferson, was duly received. My engagements are such that I can not attend.Bearing in mind that about seventy years ago, two great political parties were first formed in this country, that Thomas Jefferson was the head of one of them, and Boston the head of the other, it is both curious and interesting that those supposed to descend politically from the party opposed to Jefferson, should now be celebrating his birth-day in their own original seat of empire, while those claiming political descent from him have nearly ceased to breathe his name everywhere.

Remembering too, that the Jefferson party were formed upon their supposed superior devotion to the personal rights of men, holding the rights of property to be secondary only, and greatly inferior, and then assuming that the so-called democracy [i.e. pro-slavery Democrats] of to-day, are the Jefferson, and their opponents, the anti-Jefferson parties, it will be equally interesting to note how completely the two have changed hands as to the principle upon which they were originally supposed to be divided.

The democracy of to-day hold the liberty of one man to be absolutely nothing, when in conflict with another man's right of property. Republicans, on the contrary, are for both the man and the dollar; but in cases of conflict, the man before the dollar.

I remember once being much amused at seeing two partially intoxicated men engage in a fight with their great-coats on, which fight, after a long, and rather harmless contest, ended in each having fought himself out of his own coat, and into the coat of the other. If the two leading parties of this day are really identical with the two in the days of Jefferson and [John] Adams, they have performed about the same feat as the two drunken men.

But soberly, it is now no child's play to save the principles of Jefferson [i.e. the Declaration of Independence, and "all men are created equal"--AC] from total overthrow in this nation.

One would start with the great confidence that he could convince any sane child that the simpler propositions of Euclid are true; but, nevertheless, he would fail, utterly, with one who should deny the definitions and axioms. The principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society. And yet they are denied, and evaded, with no small show of success. One dashingly calls them "glittering generalities": another bluntly calls them "self-evident lies"; and still others insidiously argue that they apply only to "superior races."

These expressions ... [aim at] supplanting the principles of free government, and restoring those of classification, caste, and legitimacy. They would delight a convocation of crowned heads, plotting against the people. They are the van-guard—the miners and sappers—of returning despotism. We must repulse them, or they will subjugate us.

... All honor to Jefferson—to the man who ... introduce[d] into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times, and so to embalm it there, that to-day, and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression.12

Lincoln here slams those anti-national agitators (backed by the "crowned heads, plotting against the people") who claim to be heirs of Jefferson's anti-national views, but who act against Jefferson's Declaration of Independence, for counterrevolution overthrowing American nationhood!

How may this puzzle be sorted out? Lincoln cuts to the essence of the matter by identifying Jefferson as the head of one party, and "Boston," not Hamilton, as the head of the other.

Lincoln's meaning will be explained below, within the following sketch of the American political tradition that Lincoln inherited.

National Economy

Abraham Lincoln's political platform throughout his career was based on three well-known planks, which he first put forward as a follower of Henry Clay's Whigs:

- Protective tariffs,or high taxes on imports, to favor and spur our country's native industry;

- National banking,the power of a government bank to provide cheap credit for national development, countering usurers' power; and

- Internal improvements,meaning government sponsorship of infrastructure, including canals and railroads.

These elements of nationalist strategy stemmed from the humanist political philosophy of Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) and from the practice of such French regimes as that of economics minister Jean Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683). The American Revolution brought them into their most successful application. Lincoln's "Hamiltonian" program had been the Founding Fathers' national strategy to strengthen the new, weak country for permanent independence in the face of continuing fierce British opposition.

The Protective Tariff

During the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Benjamin Franklin, political father of the Revolution, organized two special meetings in Philadelphia to define the political economy of the new nation, the first at Franklin's own house in May, the second at the University of Pennsylvania on Aug. 9. These gatherings of Franklin's "Society for Political Inquiries" heard addresses composed for Franklin by Tench Coxe, on government encouragement of manufacturing and commerce for rapid American industrialization. Under Franklin's sponsorship (with Coxe's writings regularly published by Franklin's protégé, the printer Mathew Carey), Tench Coxe was to be appointed Assistant Treasury Secretary under Hamilton. Coxe would do much of the detail work for Hamilton's 1791 Report on Manufactures, the official plan of the George Washington presidential administration (1789-1797) for America's industrialization.

During the first session of the First Congress in 1789, the very first substantial act of Congress (after defining the form of the oath to be taken by Federal officers) was a protective tariff law. It was passed even before a Treasury Department was set up. All the issues which were later to be debated on this subject, were given full airing. The act specified: "[I]t is necessary for the support of government, for the discharge of the debts of the United States, and for the encouragement and protection of manufactures, that duties be laid on imported goods, wares, and merchandise."13 President Washington signed it into law. That President, and members of that Congress who voted for the law, such as James Madison, had just established the U.S. Constitution.

In his last annual message to Congress, President George Washington said, "Congress have repeatedly, and not without success, directed their attention to the encouragement of manufactures. The object is of too much consequence not to insure a continuation of their efforts in every way which shall appear eligible."14

National Banking

The Washington administration proposed, and the Congress approved, the creation of the Bank of the United States, under the stewardship of Treasury Secretary Hamilton. This Bank was an outgrowth of the Bank of North America, which had served the Continental Congress as the financial agency of the American Revolution. That earlier Bank of North America, designed by Benjamin Franklin's close nationalist allies Robert Morris, James Wilson, and Alexander Hamilton, funneled the money to the beleaguered American Revolutionary army.

Hamilton, serving as General Washington's intelligence aide, later took his and Franklin's Revolutionary bank, and made it the national bank of the republic for President Washington. Congress chartered the Bank of the United States for twenty years, from 1791 to 1811. A new twenty-year charter, for a nearly identical second Bank of the United States, was granted in 1816.

Internal Improvements

After the Revolution, General Washington sought to coordinate the actions of the states including Maryland and Virginia for the building of a canal to the Ohio River; this would connect the original coastal states to the Northwest territory which Virginia had donated to the new nation, territory to be administered by a Federal government—for which there was as yet no constitution. George Washington's effort led to a canal meeting of representatives of several states at Annapolis, Maryland, which then proposed the holding of a convention at Philadelphia. It was at this larger meeting that the U.S. Constitution was drafted. George Washington and his fellow American Revolutionists viewed the united action of society, to improve nature by great public works, to be synonymous with nationhood. After serving as the pivot for the origination of the Constitution, Washington's project for the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was eventually built as a Federal project under the U.S. Presidency of John Qunicy Adams (1825-29).

These programs taken together were the Founding Fathers' strategy for outflanking and ultimately eliminating the British legacy of plantation slavery, by guided growth, to make the U.S. an industrial and modern nation, including the south.

The Political Parties

George Washington's presidency put America's republican politics before the world; his administration was not some balancing act between aristocrat/monarchists and Jacobins, as anti-national scribblers would maintain. Rather, in 1789, Washington appointed Hamilton to Treasury, to carry out Washington's republican economic policy; and he appointed Jefferson as Secretary of State, for a republican foreign policy in accordance with Jefferson's role as the principal writer in the drafting of the 1776 Declaration of Independence.15

But two years into the Washington Presidency, Jefferson, in collaboration with Senator Aaron Burr and the Swiss aristocrat, Representative Albert Gallatin, launched a campaign of libel and dirty tricks against the administration. Washington was viciously maligned in a Jefferson-run newspaper, the Aurora; Hamilton was set up in a sex scandal and deliberately false bribery charges, the Reynolds affair, run by Burr and his cronies, and was driven from the government; and the administration's entire nationalist program was called "unconstitutional" and "aristocratic."

Burr and Gallatin were traitors, assets of the British Empire.16 But what had happened to Thomas Jefferson?

Although he was surrounded with Virginia neo-aristocracy, and married a widow with 125 slaves, Jefferson grew up a republican and was a nationalist through the period of the Revolution. He worked to prohibit and abolish feudal aristocratic family property arrangements, for religious freedom, and for public education. His program for governing the Northwest Territories outlawed slavery, and mandated public expenditures for school building and other public works. But, after the Revolution, he went to France as ambassador, and fell in among British-aligned French Enlightenment radicals, who warred against the Marquis de Lafayette and other pro-American republicans in the bloody French revolution.17

Back in America, Jefferson's aristocratic background, surroundings, and personal leanings found a convenient mode of expression in a liberal or Jacobin attack against activist government, against any program that would overthrow the planter-aristocracy. Yet, Jefferson's republican, nationalist past never entirely left him; he was to be one of America's most ambiguous figures, a rallying point for every shade of opinion.

As the British-aligned traitors Burr and Gallatin, together with the politically ambitious Jefferson, made war on the Washington administration, and formed the "Democratic-Republican" party, a supposed counter to this attack was gotten up in the form of a growing "Federalist" party, ostensibly following Washington and Hamilton. As Abraham Lincoln later accurately noted, the real center of this Federalism was not Hamilton, but the Boston Anglophile merchants, who had just been forced out the slave trade by a Caribbean slave revolt and were transferring over to opium smuggling under the protection of the British Empire—the very soul of free trade.

Working closely with their British allies, these Boston Federalists charged that Jefferson was an agent of the French, and a communist revolutionary.18 This attack on the pro-French Jefferson was used to justify a Boston demand that America should ally with France's rival, "conservative" Britain.

We now come to a central truth of American political history, which is terribly inconvenient to the neat but absurd formulas delineated above.

Every significant leader of the patriotic nationalists broke with the Boston-dominated Federalist party (though the Bostonians claimed to be followers of Washington and Hamilton). The true Hamiltonians preferred the temporary dominance of Jefferson's party, however wrongheaded and economically imbecilic it was, over allowing the outright traitors in Boston to deliver the country to its mortal enemy, the British Empire.

The nationalist, protectionist leaders who followed this course were the political heirs of Franklin and the forebears of Abraham Lincoln. Among them were Alexander Hamilton himself; Henry Clay; tariff pamphleteer Mathew Carey, father of Lincoln's economic adviser Henry C. Carey; Nicholas Biddle, president of the Second Bank of the United States; and President John Quincy Adams, son of President John Adams.

What becomes evident from reviewing the actual developments in U.S. political history, is that there is no such fight, as is presumed, between "Hamiltonians" and "Jeffersonians." The central contest is between American nationalists, and the British Empire.

- Hamilton wrote a pamphlet attacking the sitting Federalist President, John Adams of Boston, which wrecked Adams' re-election chances in 1800. Though Adams himself was a patriot, the dominant Boston element in his party was so clearly British-aligned that Hamilton knowingly swung the election against them to Hamilton's opponent on political theory, Jefferson.

The election, under the rules then in force, ended in an electoral college tie for President between Jefferson and his Vice Presidential running mate, Aaron Burr. The traitor Burr got Federalist backing to usurp the Presidential office in a House of Representatives vote; in response, Hamilton again aided Jefferson by working to sew up the House vote against Burr, electing Jefferson. In 1804, Hamilton campaigned against Burr's election as New York's governor, on the grounds that Burr and Boston Federalists were plotting to break off the northern states from the Union. Burr's disgrace and defeat led him to kill Hamilton in a duel.

- Henry Clay was politically trained in Virginia by Franklin's close ally, the Greek and Law professor George Wythe, who also trained Thomas Jefferson. Clay moved to Kentucky and rose to become the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, thus the Congressional leader of his party, the Democratic-Republicans. Despite sabotage by the Boston Federalists, Clay successfully rallied the nation for defense against British aggression, leading to the second U.S. war with Britain, which was fought to a draw.

Following this War of 1812-1815, Clay and his close ally, Mathew Carey, educated Americans on the urgent need for a return to Hamilton's economic policies.

- Mathew Carey, Irish revolutionary immigrant to Philadelphia, had worked for Benjamin Franklin in Paris, printing American Revolutionary literature. President Washington personally sponsored Carey's publishing projects, and Carey was an ardent Hamiltonian. But Carey broke with and helped destroy the Boston-dominated Federalists, and aided Democratic-Republican leader Clay to lead a war drive against Britain under the unfortunately weak President, James Madison.

From the late 1810's into the 1820's, Carey pioneered in reviving and popularizing Hamilton's protective tariff ideas, and fought for the rights of laborerers and the poor. The publisher of America's great writers such as James Fenimore Cooper and Edgar Allen Poe, Mathew Carey cooperated with the German firm of Cotta, publisher of Friedrich Schiller and a key nationalist leader like Carey.

- Nicholas Biddle headed the Bank of the United States, when the young Abraham Lincoln entered politics in the 1830's and fought to defend the Bank. Biddle had always opposed the Federalist party, was a Republican-Democrat, then voted with the Democrats rather than the Whig party; yet he was a consistent follower of Hamilton's policies. His family members in colonial times, Owen and Clement Biddle, had been members of Benjamin Franklin's secret cadre group, the Junto, which became the core of the American Revolutionary leadership.

Biddle, an ardent scholar of Classical Greek, was appointed president of the Bank of the United States in 1823. The nationalist faction, led by Henry Clay, Mathew Carey, Biddle and Secretary of State John Q. Adams, was just then gaining the political power, to allow them to pull America out of free-trade-induced economic depression.

- John Quincy Adams had a brilliant education as a teenager, reading Plato in Paris under the tutelage of American Revolutionary leader Benjamin Franklin. A U.S. Senator from Massachusetts in his father John Adams' Federalist Party, in 1808 Adams alerted President Jefferson to the design of certain Boston leaders of Adams' own Federalist Party to dissolve the Union. The traitors were prompted, Adams told Jefferson from his direct knowledge, by the British government acting through the governor of the British colony of Nova Scotia.

The enraged Boston Anglophiles removed Adams from the Senate, but he rose in public esteem as a nationalist, to be installed as U.S. President in 1825.

With Adams in the White House, Biddle at the Bank of the U.S., Clay as Secretary of State, the U.S.A. began to industrialize. The first American railroads were started, planned by Army engineers and financed by state and local governments in coordination with the Bank of the United States. The iron and coal industries boomed in Pennsylvania, as high U.S. tariffs were imposed. Philadelphia industry converted over to steam power, under the personal leadership of Carey, Biddle, and other heirs of Franklin.

While New York City's Wall Street banking center expanded as British commercial and political agents, Philadelphia's nationalists concentrated on leading the development of a U.S. industrial power base through Pittsburgh to the midwest. Philadelphia's 1820's-1830's change, under national banking and a protective tariff, shifted the city from its role as the transatlantic trade center, to become America's massive indutrial center. There are similarities to an aspect of what China is attempting to accomplish today—to reduce its dependence on a colonial-style trade from the coastal zone, and to increase its development of the west and internal continental regions.

Why Do Populists Love Foreign Bankers?

We now come to the political wars which directly shaped Abraham Lincoln's career, and led to the Revolution accomplished during his Presidential administration.

Americans these days are not too good on American history, populists not excepted. Take, for example, the populist newspaper, Spotlight. That paper tends to say things like "Andrew Jackson didn't trust the bankers; you shouldn't either"; or, that Jackson was "for the little people, against the aristocrats." This may be a popular thing to say, given the disaster caused by today's pirate globalist bankers. But the historical truth of the matter needs examining, as it bears directly on Lincoln's own struggle with Wall Street and London. Actually, it turns out that our populists are taking sides with those who aided the British monarchy, and the British bankers, the Barings and Rothschilds, and the most corrupt, thieving bankers inside America, acting against their own country.

Andrew Jackson served as President from 1829 to 1837. Under the advice of two particular men—the Wall Street slitherer Martin Van Buren, and the Baltimore slaveocrat Roger Taney—President Jackson vetoed the bill to renew the charter for the bank of the United States, and ordered the removal of the government's deposits from the Bank. These actions destroyed the protective and nurturing role the Bank had played in the American economy. After the 1836 expiration of the Bank's Federal charter, the Bank of England and British merchants withdrew credit from the financially defenseless republic, throwing the U.S. into a chaotic depression-collapse in 1837.

The fight for and against the Bank of the United States defined American politics in that era. Speaking in 1839, the young Abraham Lincoln, then a member of the Illinois state legislature, described the demagoguery, the Jacobin mob manipulation of "the little man," used by the cynical Martin Van Buren and other opponents of the Bank, as "the great volcano at Washington, aroused and directed by the evil spirit that reigns there, belching forth the lava of political corruption."19

What did Lincoln know, that today's populists don't know?

On the Bank question, Lincoln's nationalist faction was led by Henry Clay, in the Senate; Nicholas Biddle, the Bank's president; John Sergeant, the Bank's chief counsel and Henry Clay's Vice-Presidential running mate in 1832; Mathew Carey, partner of Biddle and Sergeant in launching America's greatest coal, iron, canal, and railroad enterprises; and John Quincy Adams, who, after his defeat for Presidential re-election, had gotten himself elected to the House of Representatives to keep fighting.

The main players acting against the national bank were:

- the British monarchy and associated bankers, the Bank of England, the Barings and Rothschilds, acting through their American pro-free trade agents and assets (British middle class capitalists, however, loved Biddle and the Bank because they made good money from sound investments in Biddle-promoted railroads and industries);

- Martin Van Buren, Secretary of State (1829-31), ambassador to Britain (1831), Vice President (1833-37), President (1837-41);

- Churchill C. Cambrelng, Van Buren's chief lieutenant in the House of Representatives and a paid agent of John Jacob Astor;

- John Jacob Astor, New York slumlord and international fur and opium trader, who had been started in business in London by the British East India Company in the 1780's; Astor was chief owner of the Bank of the Manhattan, which was founded by Aaron Burr, and was later called Chase Manhattan Bank;

- Alexander Brown & Sons, Baltimore and London merchant bankers who got their start serving the enemy British in the War of 1812, and financed 75% of the slave cotton going to England; Brown Brothers Harriman was a later descendant of that firm;

- Roger B. Taney (pronounced "tawney"), Baltimore lawyer and banker, U.S. Attorney General (1831-33), Treasury Secretary (1833-34), Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (1836-64);

- Thomas Hart Benton, U.S. Senator from Missouri, who got a law enacted overthrowing the government monopoly on the fur trade (instituted by George Washington to protect the Indians and the nation from British intrigues), in favor of the Astor company. He then became counsel to the Astor company. Benton called the government fur-trade monopoly a "monster"; later, he called the Bank of the United States a "monster."

Van Buren and Taney moved President Jackson to his anti-nationalist attacks, against the Bank, against infrastructure building and against protective tariffs.20

Martin Van Buren, a protégé of Aaron Burr, was a U.S. senator and New York governor, whose "Albany Regency" political machine ruled New York State before the Civil War. Van Buren and his banking partners enacted laws ensuring that bankers in the state, and the Wall Street-London banking axis, never had a more direct representative in Washington during the Nineteenth century.

The Bank of the United States, located on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia (with its president appointed by the U.S. President, and one-fifth of its directors appointed by the Federal government) controlled American credit to the advantage of internal industry, and subdued the influence of the private banker-oligarchs centered in New York. The latter wanted to have all government finances run through a new "government depository" controlled by Wall Street—just like Alan Greenspan's Federal Reserve. Biddle wrote in 1833, that the Bank war was "a mere contest between Mr. Van Buren's government bank and the present institution—between Chestnut Street and Wall Street—between a Faro [card-game] bank and a national one."

Roger Taney drew up Jackson's veto of the Bank recharter. Jackson fired two successive Treasury Secretaries, who wouldn't remove the government deposits from the Bank of the United States. He then appointed Taney, who removed the deposits; Taney put the money into the Union Bank of Baltimore of which Taney himself was co-owner and chief counsel, into John Jacob Astor's Bank of Manhattan, and into several other "pet banks."

Taney was from the nastiest element of Maryland's Anglophile, fox hunting, slave-plantation aristocracy. He was a leader of the Federalist party, whose Boston bosses hated John Quincy Adams for exposing their British intrigues to President Jefferson. When Adams ran for President in 1824, Taney backed Jackson against Adams, and went from Federalist to Jackson Democrat without missing a step. In Congress in 1834, Adams skewered Taney with this proposal: "Resolved, that the thanks of the House be given to Roger B. Taney, Secretary of the Treasury, for his pure and disinterested patriotism in transferring the use of the public funds from the Bank of the United States, where they were profitable to the people, to the Union Bank of Baltimore, where they were profitable to himself."21

This same Roger B. Taney, as Chief Justice in 1857, led the Supreme Court in rendering the infamous Dred Scott decision. Taney ruled that Negroes could not have the rights of U.S. citizens, and that the slave Dred Scott was not legally free by having gone into the northwest Federal territories—where Congress had outlawed slavery—because, according to Taney, Congress had no Constitutional power to prohibit slavery in the territories. Abraham Lincoln enraged his opponents by declaring that the Dred Scott decision was part of a "conspiracy" by Taney and other anti-national political operatives.

During the Civil War, Chief Justice Taney held to the stance, that the government had no right to stop the breakup of the Union. Taney worked constantly with pro-Confederate intriguers in Maryland, though that state remained officially in the Union. He attempted to procure the arrest of U.S. military officers, because they were obeying Lincoln's orders to stop saboteurs and spies, but could find no one to serve his writs.

III. Lincoln and the People's Contest

The conquest of power by the British free trade faction—Boston Brahmins, Wall Street and the slaveocracy—made exported cotton the political "king," drained all the gold found in California to England, to purchase manufactured goods, and eliminated the national currency formerly circulated by the Bank of the United States. When Lincoln was elected President, there were thousands of legal currencies, each petty bank issuing its own notes, and uncountable forged varieties. A panic and deep depression followed the 1857 drastic reduction of the tariff. Unemployment, hunger, and fear spread rapidly.

Lincoln began the economic mobilization while on his fateful trip to Washington for his inauguration. Speaking at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on Feb. 15, 1861, the President-elect referred to the program-section, written by Henry C. Carey, and adopted at the Republican party convention in Illinois that had nominated Lincoln the previous spring: "In the Chicago platform there is a plank upon this subject, which should be a general law to the incoming administration. That plank is as I now read:

" 'That while providing revenue for the support of the general government by duties upon imports, sound policy requires such an adjustment of these imports as will encourage the development of the industrial interest of the whole country; and we commend that policy of national exchanges which secures to working-men liberal wages, to agriculture remunerative prices, to mechanics and manufacturers adequate reward for their skill, labour, and enterprise, and to the nation commercial prosperity and independence.' "

Lincoln arrived safely in Washington, and just before his inauguration, with seceding southern congressmen having left the free-trade bloc, his forces in Congress were able to pass the Morrill protective tariff (named for Vermont Representative Justin Morrill). The act nearly doubled the duties on imported goods.

The Special Session Message

But, in the crisis of the Union, the chief task was to clarify for the people the meaning and purpose of the nation they had to defend with their lives.

In the July 4 Message, Lincoln asked elected representatives of a bankrupt, depressed country to authorize 400,000 troops, out of the north's 20 million population (equivalent today to calling for over 5 million troops), and an unbelievably large sum of money.

In that same Message, Lincoln said that the Union cause "presents to the whole family of man the question whether a consitutional republic, or democracy—a government of the people by the same people—can or can not maintain its territorial integrity against its own domestic foes. It presents the question whether discontented individuals, too few in numbers to control administration according to organic law in any case [i.e., through elections], can always, upon the pretenses made in this case, or on any other pretenses, or arbitrarily without any pretense, break up their government, and thus practically put an end to free government upon the earth. It forces us to ask, Is there in all republics this inherent and fatal weakness? Must a government of necessity be too strong for the liberties of its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?

He defended the right of an elected government to defend that power with force if need be. Lincoln's words should be of interest to today's citizens of Mexico, who are, in Chiapas, fighting a foreign-backed insurrection against their country.

Lincoln said, "Soon after the first call for militia, it was considered a duty to authorize the Commanding General in proper cases, according to his discretion, to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, or, in other words, to arrest and detain without resort to the ordinary processes and forms of law, such individuals as he might deem dangerous to the public safety. This authority has purposely been exercized but very sparingly. [It has been proposed against me] ... that one who is sworn to 'take care that the laws be faithfully executed,' should not himself violate them. The whole of the laws which were required to be faithfully executed, were being resisted, and failing of execution in nearly one-third of the States. Must they be allowed to finally fail of execution, even [if] ... some single law ... should to a very limited extent be violated? ... Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the Government itself go to pieces, lest that one be violated? ... But [I do not believe that in fact] ... any law was violated [by the Government's action]. The ... Constitution [states] that 'the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended unless, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it' ... ."

The President said the secessionists "have been drugging the public mind of their section for more than thirty years ... to take apart the government." Contrary to their "state sovereignty" propaganda, Lincoln said, states were never states out of the union, or before the union. The union created them as "states."

Could a people have their own government, that was for their own benefit, protection, and improvement, rather than be ruled arbitrarily by the powerful? Lincoln said, "It may be affirmed without extravagance that the free institutions we enjoy have developed the powers and improved the condition of our whole people beyond any example in the world. ... [T]here are many single regiments whose members one and another, possess full practical knowledge of all the arts, sciences, professions, and whatever else whether useful or elegant, is known in the world; and there is scarcely one from which there could not be selected a President, a Cabinet, a Congress, and perhaps a court, abundantly competent to administer the government itself ... . [T]he Government which has conferred such benefits ... should not be broken up."

Lincoln reported that the Confederates, in their declarations of separation from the Union, "omit the words 'all men are created equal.' Why?" he asked. "They have adopted a temporary national constitution, in the preamble of which ... they omit 'We the people' and substitute 'We, the deputies of the sovereign and independent States.' Why? Why this deliberate pressing out of view the rights of men and authority of the people?"

The President now identified the purpose of the war, the nation, and the Constitutional government, and spoke directly to the fighting citizens:

"This is essentially a people's contest. On the side of the Union, it is a struggle for maintaining in the world that form and substance of government whose leading object is to elevate the condition of men; to lift artificial weights from all shoulders; to clear the paths of laudible pursuit for all; to afford all an unfettered start and a fair chance in the race of life. ... [T]his is the leading object of the Government for whose existence we contend.

"I am most happy to believe that the plain people understand and appreciate this. It is worthy of note that while in this ... hour of trial large numbers of those in the Army and Navy who have been favored with the offices have resigned and proved false to the hand which had pampered them, not one common soldier or common sailor is known to have deserted his flag. ... To the last man, as far as is known, they have successfully resisted the traitorous efforts of those whose commands but an hour before they obeyed as absolute law. This is the patriotic impulse of plain people. They understand without an argument that the destroying the Government which was made by [George] Washington means no good to them ... ."22

The First Annual Message

By December, Lincoln was ready with his full-blown economic program. Lincoln prepared for an all-out war with the Wall Street bankers, by extended his sharp appeal to the people to defend their self-government, against oligarchism, at home and abroad. In his first Annual Message to Congress, Dec. 3, 1861, he began by warning the British Empire, in polite language, against direct military intervention on the side of their Southern surrogate warriors, and called for fortifying the Great Lakes bordering British Canada:

"A disloyal portion of the American people have during the whole year been engaged in an attempt to divide and destroy the Union. A nation which endures factious domestic division is exposed to disrespect abroad, and one party, if not both, is sure, sooner or later, to invoke foreign intervention.

"Nations thus tempted to interfere, are not always able to resist the counsels of seeming expediency and ungenerous ambition, although measures adopted under such influences seldom fail to be unfortunate and injurious to those adopting them. ...

"... Since ... foreign dangers necessarily attend domestic difficulties, I recommend that adequate and ample measures be adopted for maintaining the public defenses on every side. While, under this general recommendation, provision for defending our seacoast line readily occurs to the mind, I also in the same connection ask the attention of Congress to our great lakes and rivers. It is believed that some fortifications and depots of arms and munitions, with harbor and navigation improvements, all at well-selected points upon these, would be of great importance to the national defense and preservation."

Lincoln then argued, "It continues to develop that the insurrection is largely, if not exclusively, a war upon the first principle of popular government and the rights of a people ... ." He said the insurgents were attacking the right of suffrage, proposing in their Confederacy to deny popular election of any but legislators. Among the Confederates and their supporters, Lincoln said, "Monarchy itself is sometimes hinted at as a possible refuge from the power of the people."

The President now struck hard, to rally support for his coming political showdown with the Money Power:

"In my present position, I could scarcely be justified were I to omit raising a warning voice against the approach of returning despotism."

Lincoln warned that there was an "effort to place capital on an equal footing with, if not above, labor in the structure of government." It is, Lincoln said, falsely "assumed that labor is available only in connection with capital; that nobody labors unless somebody else, owning capital, somehow by the use of it induces him to labor." It is then falsely "concluded that all laborers are either hired laborers, or what we call slaves. And further, it is assumed that whoever is once a hired laborer, is fixed in that condition for life.

"Now, there is no such relation between capital and labor as assumed," Lincoln said, "nor is there any such thing as a free man being fixed for life in the condition of a hired laborer ... ."

"Labor is prior to and independent of capital," the President declared. "Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. ..."23 He went on to describe the conditions of life in a self-governing nation-state, whose ordinary citizens have the actual opportunity, not only the theoretical right, to substantially improve their condition and rise in society.

Lincoln closed the message by stating, "There are already among us those who, if the Union be preserved, will live to see it contain 250,000,000 [people]. The struggle of today is not altogether for today; it is for a vast future also ... ."24

Within a week, President Lincoln's financial plan was presented by Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase (a free-trade liberal sweating in the President's harness):

- a nationally regulated private banking system, which would issue cheap credit to build industry;

- the issuance of government legal-tender paper currency;

the sale of low-interest bonds to the general public and to the nationally chartered banks.The overall program was to include: - the increase of tariffs until industry was running at full tilt;

- government construction of railroads across the continent, and into the middle South, promoting industrialism over the Southern plantation system;

- the creation of a separate Agriculture Department of the government, to make farmers scientific and successful;

- free state colleges throughout the country, arranged for by the Federal government;

- the recruitment of immigrants, especially for the intense settlement and development of modern conditions in the western and Pacific states.

When Secretary Chase's report was submitted to Congress, the House Ways and Means committe chairman was Thaddeus Stevens, a Pennsylvania iron manufacturer, a dedicated follower of Henry Carey's protectionism, and an old comrade-in-arms of John Quincy Adams in combatting British intriguers. Lincoln was to rely on Stevens and other such fierce partisans of the Union cause to get his program through.

War with the Bankers

The messages of Lincoln (Dec. 3) and of his Treasury Secretary Chase (Dec. 10), brought the expected horrified reaction from the London-Wall Street axis. On Dec. 28, 1861, New York banks suspended payment of gold owed to their depositors, and stopped transferring to the government the gold which they had pledged for the purchase of government bonds. The banks of other cities immediately followed suit.

James Gallatin, the smugly aristocratic son of Albert Gallatin and lifelong associate of the British Crown financiers, headed a delegation of New York bankers who came to Washington to meet with the administration and Congress. His program contradicted the President's. First, the Treasury must deposit its gold in private banks, and let those banks pay the government's suppliers with checks, keeping the gold on deposit for the investment use of the bankers. Second, the government should sell high-interest bonds to these same banks, for them to resell to the European banking syndicate. Finally, the war should be financed by a heavy tax on basic industry.

Gallatin was shown the door. Lincoln had no choice but to defy London and Wall Street or lose the country. As James Blaine wrote,25 British bankers such as the Rothschilds would not touch our securities. Confederate bonds were more popular in England than those of the U.S. government. Blaine called the Civil War a three-fold contest: military versus the Confederates, diplomatic and moral versus the British and French governments, and financial versus the money power of Europe.

The U.S. could borrow only at usurious interest rates. It was the general opinion of the European elite that the American Union would be dissolved.

Under suspension of gold ("specie") payments by the bankers, state-chartered banks might flood the country with worthless paper, and there would be no national currency. The banks of leading American cities would not accept U.S. Treasury notes.

But the day the New York banks suspended, Lincoln's bill for the government to print $150 million in Federal money was introduced in the House of Representatives. The notes, to be printed green, would come to be called "greenbacks." Floor debate occurred in late January. New York's bankers'-boy Congressman Roscoe Conkling protested against the projected currency issue, citing as his authority in political economy, the London Times, which, he said, hails the $150 million as the dawn of American bankruptcy, the downfall of American credit. For its part, the London Times later confessed that they did not know why greenbacks did not destroy the U.S. economy, contrary to their supposed laws of economics.

Ohio's Congressman John Bingham struck back against "efforts made to lay the power of the American people to control their currency, a power essential to their interests, at the feet of the brokers and of city bankers who have not a tittle of authority, save by the assent or forebearance of the people to deal in their paper as money."26

Congress authorized the greenbacks, and on June 7, 1862, Secretary Chase asked for another $150 million issue. The tariff act of July 14, 1862, again sharply increased the duties. Lincoln and his adviser Henry Carey raised the average of duties on all imported goods from 15% to 33% by 1863, and then to 48% by 1866. Iron and steel tariffs were radically increased, virtually forcing into existence an American steel industry for the first time.

Jay Cooke, banker of the Philadelphia Carey-led industrialists, was hired to sell small government bonds to the ordinary citizens; with 2,500 sub-agents, Cooke sold over $1.3 billion worth of bonds from 1862 to 1865.

President Lincoln used more of his influence in Congress to press for his national banking bill, than for any other legislation. New England and New York bankers instructed their congressmen, such as Sen. Roscoe Conkling, to defeat the proposal. Lincoln's increasing prestige and authority won out, and he signed the National Currency Act on Feb. 25, 1863, and the National Bank Act on June 3, 1864.

Lincoln's National Banking, while it was not the old Bank of the United States killed by banker mob leaders in the 1830's, was an important step back to national sovereignty and financial order. The state-chartered banks did not have to apply for the new Federal charter, but Lincoln threatened to tax them heavily if they didn't. Only credit-worthy banks qualified, and they were subject to regulations as to minimum capitalization, reserve requirements, the definition of bad debts, public reporting on financial condition and ownership, and other elements of security for depositors.

Every bank director had to be an American citizen, and three-quarters of a bank's directors had to be residents of the state in which the bank did business.

Each bank was limited in the interest rate it could charge, by its state's usury laws; or, if none were in effect, then to 7%. If it were caught exceeding this limitation, it would forfeit the loan in question, and would have to refund to the victimized borrower twice what he had paid in interest.

A national bank had to deposit with the Treasury, U.S. bonds amounting to at least one-third of its capital. In return, it would receive government-printed notes, which it could circulate as money. Thus, the banks would have to lend the government substantial sums for the war effort, to qualify for Federal charters, and a sound currency would be circulated to the public for an expanding economy.

Meanwhile, national banks could not circulate notes printed by themselves. In order to eliminate all competition with the new national currency, the notes of state-chartered banks were hit with a massive tax in the following year.

Most large commercial banks organized themselves according to the new system, and many new large banks were formed as national banks. Despite historically unprecedented financing needs, the government raised,27 and printed, the cash to fight and win the Civil War. With the combination of banking, tariff, educational, and agricultural measures enacted under Abraham Lincoln, the United States began the greatest period of industrial development ever seen anywhere.

America was recorded to have produced less than 12,000 tons of steel in 1860. New government-protected mills flourished, filling orders for government-subsidized railroads and for tractors going to farmers on government land grants. By 1880, American steel production had risen a thousandfold, to 1.2 million tons, and soon surpassed Britain in leading the world.

In about the same twenty-year period, railroad mileage more than tripled, the number of patents issued tripled, coal production and woolen manufacturing quadrupled, and output of petroleum (invented as an industrial product by the Philadelphia nationalists) went from nothing to 1.2 billion gallons.

Lincoln's Philadelphia nationalists also organized the creation of the electrical industry. The science-industrial-military-educational complex, based in Philadelphia and intersecting the West Point and Annapolis military academies, had its greatest leader in Alexander Dallas Bache, great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin, and President Lincoln's principal scientific military adviser. From the 1830's through the 1860's, Bache had coordinated American science work in an alliance with the most profound European scientists, in particular Carl F. Gauss and Alexander von Humboldt. By 1880, through Bache's Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, and through Henry Carey-led Philadelphia industrialists, Thomas Edison had been given a laboratory in Menlo Park, N.J., had been protected from Wall Street predators, and had been advised and commissioned to invent electric lights and public electric power. With partners in Europe, the scientific and industrial republicans backing Edison managed to spread the totally new power source to much of the world. Through the harnessing of electrical energy, Man's mastery over nature increased a thousandfold. And thus, modern times emerged.28

Both the scientific tradition of Carl Gauss, the fruit of the Fifteenth-century Golden Renaissance; and the republican political philosophy of Leibniz, from the same Renaissance view of man as "little lower than the angels"; found expression in the work of Abraham Lincoln and his supporters.

Lincoln's revolution provided the industrial muscle to win the war for the Union, and to free the slaves. His revolution dignified national life, putting Lincoln's well-beloved face into most men's mental image of the United States of America. In doing so, Lincoln pulled American society out of a condition of degradation and demoralization, that had prevailed in the generation before the Civil War. The precious heritage of that revolution remains of immense value to us in the world's present financial and political crisis.

Notes

1. Special Session Message, July 4, 1861, Messages and Papers of the Presidents, (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of National Literature, 1897), Vol. 7, p. 3228.

2. Chicago Tribune, Feb. 13, 1861, p. 1, col. 1, cited in J.G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Springfield to Gettysburg (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1945), Vol. 1, p. 275.

3. Chicago Tribune, Jan. 4, 1861, p. 3, col. 3, cited in ibid.

4. Alexander K. McClure, Lincoln's Yarns and Stories (Grand Rapids: Bengal Press, 1980, reprint), p. xv. This Col. Scott was later president of the Pennslyvania Railroad.

5. Ibid., p. 180.

6. John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln, A History (New York: The Century Co., 1917), vol. 4, p. 138.

7. Message to Congress, May 26, 1862, reported in the Congressional Globe, page 2383.

8. Executive Order, April 25, 1861, in Messages and Papers, op. cit., Vol. VII, pp. 3218-3219.

9. Ibid., p. 3219.

10. Special Session Message, in Messages and Papers, op. cit., Vol. 7, p. 3227.

11. The Times. London, Aug. 10, 1861, cited in Randall, op. cit., p. 388.

12. April 6, 1859, letter to Henry L. Pierce and others, quoted in Richard N. Current, editor, The Political Thought of Abraham Lincoln (Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill Company, 1967); Pierce, a free trader, later openly opposed Lincoln's protectionist tradition.

13. Cited in Richard W. Thompson, The History of Protective Tariff Laws (New York: Hill & Harvey, 1888; reprinted New York: Garland Publishing, 1974).

14. Eighth Annual Address, Dec. 7, 1796, Messages and Papers op. cit., Vol. 1, p. 193.

15. When the Continental Congress decided on independence from Britain, they appointed a committee including Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson, to draft the reasons for the separation. The committee chose Jefferson, a good writing stylist, to prepare the draft, which was amended by Franklin and Adams.

16. See Anton Chaitkin, Treason in America: From Aaron Burr to Averell Harriman (New York: New Benjamin Franklin House, 1985; out of print, to be republished by Executive Intelligence Review).

17. Jefferson himself later concluded, and wrote to Lafayette, that "British gold"—that is, the British secret service—had "anarchized" the French revolution.

18. It is a delicious irony that the supposedly Jeffersonian (i.e., anti-Hamilton, anti-Lincoln) John Birch Society, has reprinted Proofs of a Conspiracy, by the British gentleman John Robison. The Boston Federalists smeared Jefferson with Robison's charge that communist masons, the Illuminati, had overthrown the French King. (Meanwhile, the Birchers assure their readers that British masons are conservative "good guys.")

19. Dec. 26, 1839,

20. Patriotic Democrat advisers Joel Poinsett and Sam Houston worked contrarily, attempting to hold down Jackson's rage and political insanity. Jackson had killed over twenty people in duels.

21. Adams' speech containing this mock resolution was suppressed by the Jackson forces in Congress, so he had it privately printed, and Biddle distributed 50,000 copies; a copy is in the Library of Congress rare book collection.

22. Special Session Message, July 4, 1861, Messages and Papers op. cit., pp. 3230-3231.

23. First Annual Message, Dec. 3, 1861, Messages and Papers op. cit., p. 3258.

24. Ibid., p. 3259.

25. James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress: From Lincoln to Garfield, with a Review of the Events Which Led to the Political Revolution of 1860 (Norwich, Conn.: Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1884).

26. Bingham later was a principal author of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, providing citizenship to freed slaves and immigrants; was a member of the military court which tried Lincoln's assassins; and served as U.S. ambassador to Japan in the 1870's and 1880's, when the Lincoln nationalists spread the industrial revolution and modern times to that country (see Box, "The Lincoln Revolution Overseas," p. XX).

27. In addition to the revenue raised from customs duties, a wartime income tax was imposed, falling mostly on the rich (3% on incomes of $600-10,000; 5%, and later 10%, on incomes over $10,000), and sales taxes also, falling heaviest on liquor. These taxes were phased out after the war. Customs duties remained the normal mode of government revenue generation in America, until the Anglophile Woodrow Wilson brought in the permanent income tax in 1913.

28. Anton Chaitkin, "The 'land-bridge': Henry Carey's global development program," and works and authors cited therein, in Executive Intelligence Review, May 2, 1997 (Vol. XX, No. XX), pp. XX-XX.

———————————————————————————

Lincoln's revolution had powerful enemies, and still does. Have they influenced you, even against your will, in your conceptions of history? This test may be of interest.

Pose for yourself, the question, "what was the official verdict in the Lincoln assassination?," and imagine posing it to others. Among all but a small minority, the answer would be, either:

(a) that "the official verdict was a 'lone assassin,' John Wilkes Booth, and I support that verdict because I am not a conspiracy theorist"; or,

(b) that "the official verdict of a 'lone assassin' was a coverup, and I don't agree with it."

Now, in the case of many readers, it can be shown that the reader who goes along with either (a) or (b), already knows that the truth is neither one, but somehow cannot let himself think in accordance with such a disturbing truth.

In fact, the official verdict of the United States government was that Lincoln's murder was a conspiracy, hatched in the British Empire, in the British army-occupied colony of Canada. The assassin John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate spy, went there in 1864 to collaborate on the plans for attacking Lincoln with known British agents such as George Sanders, a member of a terrorist team with British Col. George Grenfell and others. Montreal, Quebec, hosted the Confederate secret service; the group of Confederates stationed there were nicknamed the "Canadian Cabinet" of the Confederacy.

Two days before his agents caught up with Booth, U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton wrote that, "This Department has information that the President's murder was organized in Canada and approved at Richmond."*

A week after the Stanton memo, President Andrew Johnson, who had succeeded Abraham Lincoln, issued a proclamation offering rewards for the capture of those suspected of running the assassination: "It appears from evidence in the Bureau of Military Justice that the ... murder of ... Abraham Lincoln ... [was] incited, concerted, and procured by and between Jefferson Davis, late of Richmond, Va., and Jacob Thompson, Clement C. Clay, [Nathaniel] Beverly Tucker, George N. Sanders, William C. Cleary, and other rebels and traitors against the government of the United States harbored in Canada."**

In the military commission trial convened on May 9, 1865, David E. Herold, George A. Atzerodt, Lewis Payne, Mary E. Surratt, Michael O'Laughlin, Edward Spangler, Samuel Arnold, and Samuel A. Mudd were charged with "conspiring together with one John H. Surratt, John Wilkes Booth, Jefferson Davis, George N. Sanders, Beverly Tucker, Jacob Thompson, Clement C. Clay ... and others unknown to kill and murder ... Abraham Lincoln ... ."

All of these defendants except Spangler were found guilty of this conspiracy. Herold, Atzerodt, Payne and Mary Surratt were hanged and the others jailed on the island of Dry Tortugas, Florida.@sd

During the trial, the government presented many witnesses who established John Wilkes Booth's participation in the Canadian-based Anglo-Confederate secret service.

Now, to complete the test, ask yourself if you may ever have seen the accompanying very famous photograph, of the persons who were hanged for the conspiracy to murder Abraham Lincoln. If perchance you have seen it, or even heard of it, then ask yourself why does such evidence somehow not register in the mind, in connection with the question, what happened in the Lincoln murder?

It is because Twentieth-century reporters and historians have succumbed to a long propaganda war, run by the British and the pro-Confederates, to the effect that the official verdict of the U.S. government should be ignored, because the heritage of Lincoln was then so strong as to make of our government a bunch of fanatics—even "pro-Negro fanatics," as some would have it—and therefore, the official verdict in the case is "just a conspiracy theory" now, after the Lincoln legacy is supposed to be dead.

[NOTES]

* Stanton to Major-General John A. Dix, April 24, 1865, in War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I, Vol. XLVII, Pt. 3, p. 301.

** Proclamation, May 2, 1865, Messages and Papers of the Presidents (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of National Literature, 1897), Vol. VIII, p. 3505.

@sd Ibid., pp. 3540-3546.

————————————————————————————

Abe Lincoln Stood Up to the Imperial Liars

As a Congressman in 1847, Abraham Lincoln boldly exposed the British faction's lying pretexts for the Mexican War. Lincoln risked his career, helping lay the basis for the nation's survival under his own future Presidency.

He and his fellow nationalist leaders knew then that the British Empire subversively guided the political faction which had launched the unnecessary and unjustified war against Mexico (1846-48).

Three years earlier, in the 1844 elections, Lincoln's Whig Party had issued a pamphlet proving that the British were financing the "Free Trade" campaign of James K. Polk, against his rival for the Presidency, the protectionist, nationalist Henry Clay. In their pamphlet, Lincoln's party asked patriots to decide "whether British gold shall buy what British valor could not conquer"—that is, what the British couldn't conquer during America's Revolution and the War of 1812. Quoting from British newspapers and from the literature of Prime Minister Robert Peel's free-trade political movement, the Whig pamphlet documented the British transfer of at least $440,000 (equivalent to hundreds of millions today) to put behind the Polk campaign.

The Mexican War arose out of a dirty arrangement between the British Empire and British agents guiding the Polk administration—led by Navy Secretary George Bancroft and expansionist slaveowners.*

Although he had campaigned for the Presidency on a slogan ("54-40 or Fight") indicating that he would entirely exclude the British from the Pacific Coast, Polk suddenly agreed to British demands that they be given title to half of the region between California and Alaska, "the Oregon territory," in return for British tacit backing for U.S. aggression against Mexico. To secure a declaration of war, Polk lied to the Congress, that Mexico had invaded the U.S. and shed American blood on American soil. Britain thereby stretched its Canadian colony out to British Columbia, and the U.S. got endemic hostility with its sister republic to the south. The U.S. would pay $15 million for California, after stealing it in the war.

In December 1847, Congressman Lincoln challenged this swindle by introducing what became known as his "Spot" resolutions. He posed the issue as follows: "[T]his House desires to obtain full knowledge of all the facts which go to establish whether the particular spot of soil on which the blood of our citizens was so shed, was, or was not, our own soil, at [the commencement of the war]." The resolutions then went on to demonstrate beyond doubt that the Mexicans had not invaded U.S. soil, thus proving the war pretext a lie.

Lincoln paid a price for undermining popular delusions, and standing up to the British and their banker and slaveowner allies. He could not be renominated for Congress. Lincoln never held another elected office until, in the crisis brought on by the powerful treasonous faction he had challenged, he was elevated to the Presidency to save the nation.

* See Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., "The Lesson of The 'Spot' Resolutions," and Anton Chaitkin and John C. Smith, Jr., "How Britain's Treason Machine Made War Against Mexico," in The New Federalist, Dec. 22, 1997 (Vol. XX, No. XX). A copy of the Whig Party 1844 election pamphlet is held by the Library of Congress; there is no individual attribution as to its author.

The Lincoln Revolution Overseas

America's Civil War was a contest for the whole world. Lincoln's nationalist supporters carried their revolution abroad to Germany, Russia, Ireland, Japan, China, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and other nations. Everywhere, the British Empire sought to stop alliance with the U.S.A., and to prevent the adoption of the American model of rapid industrialization and political nationalism.

German nationalists, profoundly moved by Lincoln's life and death, worked directly with Henry Carey, and in 1876-80 converted Germany from British free trade to American protectionism and state-sponsored industrialization. Britain's murderous response led to World War I.

Czar Alexander II, who freed the serfs in tandem with his ally Lincoln, worked with Carey's organization for Russia's industrialization and a Russia-U.S. military alliance against the British. The Czar and the American President James Garfield, both followers of Lincoln, were assassinated with a few months of each other in 1881. Lincoln's Pacific Railroad superintendent, General Grenville Dodge, advised Russia on its Trans-Siberia railroad, built with Pennsylvania steel and locomotives.