Highlights | Calendar | Music | Books | Concerts | Links | Education | Health

What's New | LaRouche | Spanish Pages | Poetry | Maps

Dialogue of Cultures

Lyric Song and the Birth

of the Korean Nation

by Kathy Wolfe

This article is reprinted from FIDELIO Magazine, Summer 1996, Vol. VI, No. 2

Please note that this online article contains only a few of the several examples in the original published version. To purchase the article and Fidelio magazine, contact schiller@schillerinstitute.org

Related Articles:

Interview with Lee Soo-in, Korean Master Composer: from FIDELIO Magazine,

Vol V, No. 2 Summer 1996

Great Song is Universal: Italian, German, Korean, English, Czech,

Russian and Danish examples at C=256HZ (pdf formant)

Lyric Song and the

Birth of the Korean Nation

by Kathy Wolfe

During the 1920's, an outpouring of lyric song began in Asia, on the Korean peninsula, which carried forward the European Renaissance tradition of bel canto and poetic metaphor. It was the more striking, as this art had all but died in Europe, with the 1897 death of Johannes Brahms. Some of these Korean Lyric Songs more resemble those of Verdi or Brahms of the 1870's, than the junk music produced in the West after 1920.

Korean historian Dr. Lee You-sun, in his book, The History of Western Music in Korea,1 proposes these songs be made known the world over, much as the lieder of Franz Schubert are known. Indeed, the Korean Lyric Songs (Hanguk Kagok) demonstrate truths about art and man, in the same way as Schubert's world-famous lieder do.

During the 1890's a movement arose, associated with Brahms and his disciple Antonin Dvorak, to spread the "technology" of Classical music around the world, before it was destroyed in Europe. For example, as Dennis Speed has shown, African-Americans, spearheaded by the work of Harry T. Burleigh, who studied with Dvorak during his 1892-5 stay in America, extended this "Project Brahms" to the U.S., creating the American art song in English—the Negro Spiritual—using Classical principles.2

|

An Appreciation "The art and culture of China, Japan, and Korea are well known in the West, but the "Korean Lyric Song," and its history, have never, to date, been introduced to a Western readership, for lack of an available forum. "Thus, the appearance now of this fine article on Korean Lyric Songs by the Schiller Institute's Kathy Wolfe, is very important and precious, for it allows the English-speaking public to encounter these songs for the first time. This is to the glory of Korea, and the Korean people." Dr. Lee You-sun, |

|||

In that very same era, the German conductor Franz Eckert, and American missionaries who were the heirs of the victorious Civil War faction of Abraham Lincoln, traveled to Japan and Korea, and brought with the Christian religion and its hymnals, the basic principles of European bel canto and Brahms' compositional method. In Korea, especially, the creation of songs in the Korean language according to these exciting new principles, caught fire—songs which were, for the first time, in the language of the Korean people. Because Korea was an occupied country, virtually a province of China, these songs became the voice of her national independence movement against foreign, and feudal, domination. Korean Classical composition would continue, through the Japanese Occupation and the tragic post-War division of Korea, just as African-American composers such as Hall Johnson continued their work well into the 1940's.

Today, Classical composition is dead thoughout the world. But if humanity is to survive its current crisis, the culture of Classical music and art must be revived, and it is to that purpose that Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., initiated the Schiller Institute's work in music. It is therefore a privilege to meet individuals within whose living memory Classical composition still thrived, and the author wishes to thank Maestro Raymond Cho of the Los Angeles Korean Philharmonic Orchestra for introducing her to Korean Lyric Songs; Dr. Lee You-sun, who is a living monument to history, as is his book; and choral composer Dr. Kwon Gil-sang. In the study of Classical composition, one regrets sometimes that most of one's friends—such as Mozart and Schubert—have passed away. It is a joy to find new ones.

Great Song Is Universal

Comparing at once the Korean Lyric Songs, the African-American Spirituals, the lieder of Schubert and Brahms, and the arias of Mozart and Verdi, it is striking to see the absolute universal nature, for all mankind, of the scientific principles of Classical composition.

Make no mistake; we do not mean that "all people got rhythm." Most of what passes for music today is garbage, from Schoenberg, to Gershwin, to rap, to Buddhist chant.

Instead, music, to be Classical, must obey specific scientific laws. These were first created in the Italian Renaissance, with the rise of the bel canto method, based on the lawfulness of the human singing voice. These laws were advanced by Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, using counterpoint, and Motivführung (motivic thorough-composition).3

Begin with bel canto, created in the Cathedral of Florence in the early 1400's by the Renaissance genius Filippo Brunelleschi, working with musicians such as Guillaume Dufay. They invented the bel canto "round sound," whose earliest representation can be seen in the Cathedral's 1436 Cantoria sculptures commissioned by Brunelleschi [see: Figure 1].

The basis of bel canto is voice registration. True bel canto can only be taught as speech is taught: from early childhood. In the Renaissance, all children who came to church were taught to sing. After hundreds of years of training children to sing—not just a few star pupils, but very large numbers, whole towns of children—musicians found that children must be taught to shift registers when moving from the lowest, or first register (I) (shown shaded), up to the second, or center register (II) (shown unshaded), that is, between F and F-sharp [see: Figure 2]. Children taught to make this register shift, developed beautiful voices, and could sing well into old age.

As adults, the average tenor or soprano must also make a register shift, from the central, to the high or third (III) (and fourth, IV) registers, also between F and F-sharp [see: Figure 3].

This accounts for the central importance of Middle C as "Middle C": only the octave so placed, will be divided in half by the most common voice register shift.

European Classical composers such as Mozart, Haydn, and Schubert, were all trained in bel canto singing as children. They heard registers as truly different voices, which they used to create poetic dialogue, and hence, metaphor. For example: Giuseppi Verdi sets the tenor voice in "Celeste Aida," in the second, central register for the opening words, "Heavenly Aida, divine beauty," which rise to the top limit of the central register on a high F-natural, accenting this F twice. But then, Verdi wants to introduce a new poetic voice, to be heard at the entrance of the new idea, "mistico serto di luce e fior (mystical garland of light and flowers)"—so he introduces the F-sharp, and with it, the dramatic new quality of the tenor's third, high register, which also introduces, briefly, a new key [see: Figure 4].(Click here for example)

The poetic metaphor depends upon the shift in registers. In the first lines, the singer admires Aida's physical beauty; at "mistico serto," however, he reveals something deeper: he loves her soul.

Just so, Korean patriot Kim Dong-jin in "Azaleas (Chindallae-ggot)," writing in 1960, after the partition of Korea, created a musical metaphor—the longing for national reunification—which could not be stated in words. He did this using this same Classical principle of registers. In the original poem by Kim So-weol, written in 1932 during the Japanese Occupation, when patriotism was a crime, a woman sings that she will strew azaleas from Yongbyon in the far North, before her sweetheart, as he leaves her. She asks only that he tread lightly upon them. The image of the soul of the nation being trod upon is clear.

Kim Dong-jin's opening musical refrain, "If you wish to leave me, I'll let you do so without a word," lies in the soprano's second, center register (as in "Celeste Aida"), testing the upper limit at F twice [see: Figure 5]. But at the pivotal development passage, "Going step by step on the flowers lying there, gently, softly tread as you go," the soprano shifts to the lower, first register, to emphasize that the flowers have been cast on the ground, and then rises to a fermata on the G in the high, third register, to dramatize the verb phrase "tread lightly" [see Figure 6].

To achieve the lawful use of vocal registers, Classical composition requires a specific tuning, which was used from the Renaissance until the death of Brahms. The division of the scale in Figure 2 (C scale) is based on the natural, God-given law for the human voice—people the world over are born with these voice registers. The C scale depends on them, with the specific pitch C=256 Hz determined (about A=430 Hz). All Classical composition from the 1430's to the 1830's used this C=256.

Beginning with the influence of the irrationalist Richard Wagner, however, the opponents of Classical music began to raise the pitch, up to A=440, and in some cities such as Vienna today, to almost A=450. This destroys the voice, and the poetic dialogue intended by Classical composers. At the higher A=440 pitch, for example, a tenor singing Verdi's Aida would be forced to "cover" the high F-naturals (that is, to shift them to the third register), right in the first phrase, since this F-natural is much higher than it would be at the A=430 pitch which Verdi assumed [see: Figure 7]. Now, rather than a new voice entering at the new poetic line "mistico serto," the third register sound comes in at the very beginning, and becomes an annoying repetition. The poetry is destroyed.

This is the reason why, in 1884, Verdi proposed that a law setting a ceiling on the pitch of A=432 be established in Italy, and why Brahms continued to compose at A=430 until his death in 1897. A=430 became known as the "Mozart-Verdi" tuning.

Similarly, in "Azaleas," if the pitch is heightened, the opening high F-naturals are forced up into the soprano's third register [see: Figure 8]. With the third register already reached, there is no new poetic voice available to create change at the later climactic phrase "tread lightly" at the high G [Figure 6]. Instead of the poetic transformation intended by the composer Kim (as shown in the motion from Figure 5 to Figure 6), at the heightened pitch of A=440, there is only repetition, as is shown in the motion from Figure 8 to Figure 6.

Notice also Kim's use of the deeper first register, at the original lower pitch of C=256, in Figure 6. The distinct, rich quality of these first register notes is obscured, when this passage is raised higher at modern A=440 pitch (not shown). All the F-naturals, which are in the first register at the original, lower pitch in Figure 6, would, at A=440, be forced up into the second, central register. Raising the pitch arbitrarily changes the composer's original intentions.

Thus, the Mozart-Verdi tuning is necessary, for the Korean poetry to be understood. And, when the author pointed this out at a master class in Los Angeles recently, a Korean singer in the audience volunteered, "Certainly, that's because we based it on our study of Mozart and Beethoven!"

Classical composition in Korea continued into the post-war period, for historical reasons detailed below. Here, note that when "Azaleas" was written, many places in the world still insisted on the Verdi tuning; for example, according to Maestro Carlo Bergonzi, the New York Metropolitan Opera tuned as low as A=435 until the late 1950's. In Tokyo and Seoul, the influence of Verdi and Brahms was still keenly felt.

Song of My Homeland

Dr. Lee Soo-in, composer and director of the Korean Broadcasting System Children's Choir, wrote "Song of My Homeland (Kohyang-ui no-rae)" just after the Korean War, in Seoul, in 1955. Koreans often say the original poem by Kim Chae-hyo is so beautiful that it cannot be translated, but here is some sense of it:

Chrysanthemum petals have fallen,

In the winter garden;

Open the window, and white,

Early frost comes down.

Now, with out-stretched wings, the geese

Northward take flight.

Oh, look from this lonely place,

Over quiet, empty fields:

The way to our Homeland is covered in snow;

Yet, a small flower's flame may burn beneath.

The moon is gone, the sun is gone too;

The stars are far away... .

By the deep mountain valley stream,

There is a village, in early autumn.

But spring will come, please don't go—

Flower parties will be so joyous then.

Oh, put your hands together,

And cover your eyes:

The walls of our Homeland house

Are covered thickly with snow.

Lee Soo-in's song opens with an accompaniment in the style of Bellini, and proceeds in a long legato line through the center register, to rise to a high F at the top of the register on "[in the] winter garden." The song is strophic, so this same opening musical phrase takes on far more meaning with the second verse, in which the high F is reached in the lovely phrase "[the] stars are far away." The melody is clearly based not on the words of the first, but on the words of the second, verse [see: Figure 9].

This illustrates Brahms' concept of the strophic song, in which the same melody is repeated for multiple verses of a poem. Brahms called this the "highest" song form. In order to create a melody fine enough to sustain several different verses, Brahms taught, the composer must not set the literal words, but rather the deeper, "unspoken" metaphor of the poem as a whole.

According to a biography of Brahms by his student Gustav Jenner, Brahms sharply criticized musicians who just "compose-out the first strophe of the poem, according to which the rest of them can be 'sung off.' " Instead, Brahms said, a composer must create a melody which "has welled up from that same single, deep emotion, from which flowed all the images of the poem, which are so manifold, and yet always say the same thing anew." Brahms praised one Schubert song, saying: "It is a musical expression of what the entire poem left as an impression within the composer; and so we find that with each new strophe, as always with Schubert, it glows more fully and seems to say new things, because with each new text, the underlying emotion becomes increasingly distinct, and is expressed with increasing intensity."4

What is the unspoken metaphor here? The stars, of course, are always far away. There is something even higher than the stars, for which the soul longs.

Returning to the first verse, Lee outlines the opening two phrases in the central register voice, setting the scene, which is passive [see: Figure 10]. Then, he proceeds to introduce a change, a verbal action, and he has the legato line rise to the register shift on the high G, into a new register, as the verbal action has the geese "take flight" (G) to the North.

It is not necessary to digress to geopolitics to understand the profound effect of this image on South Koreans, separated from their nationhood, from their countrymen and families in the North, by the De-Militarized Zone. Yet the emphasis is on hope, on soaring above obstacles; in the second verse, the promise of spring brings a third register shift, on the verb phrase "will be joyful."

It should be obvious that this song requires the Verdi tuning, for this striking shift from the bare opening lines, to the new idea of hope, to be heard as the composer wished. The author recently presented a master class on the Mozart-Verdi tuning of C=256 at Philadelphia's Temple University, and we compared this song sung at the lower Verdi tuning, with the modern, heightened pitch. At the heightened pitch, the initial F is pushed up into the higher register, right in the opening scene, leaving nothing to add when the geese "take flight" [see: Figure 11]. The audience found this song to be the one most dramatically changed for the better at the lower pitch—obviously the composer's original intention—which gave it a much sweeter and more profound quality.

All this proves that such a rigorous, musical science, although invented in Italy or Germany, is not national or "racial"—it is human; and there is only one human race. Such a science belongs to all mankind, just as does any technology, such as agriculture, the wheel, or electricity. And conversely, any music—such as Schoenberg, Gershwin, rap, or Buddhist chant—which does not then utilize these laws, is not human—just as a cart without wheels, is not a cart, and will not run.

At the center of this musical science is the Renaissance concept of Man in the image of the living God, imago viva Dei. All men are created with a "divine spark" from God, which makes each individual free. Yet, this divine spark means nothing, unless we use it to continue God's creative work. In human terms, this is to build our nations, especially through the higher arts such as language, poetry, and music.

The remarkable unity of thought behind the seven international songs presented in the Appendix, demonstrates the universality of this principle [see: Appendix, (PDF file)]

The spread of "Project Brahms" to Korea began shortly after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. During the Lincoln era and through the term of President Ulysses S. Grant, American advisers and missionaries traveled to Japan, to help the Meiji Restoration combat the machinations of the British Empire, such as the Opium Wars, which enslaved China and other Asian nations.

Westerners were forbidden in Korea by the feudal nobles in Seoul, but word spread of the fabulous American technological revolution in Japan during the 1860's and 70's—and of the Gospel. When the American missionary Rev. Alexander Williamson arrived in Manchuria in 1867, Korean intellectuals eager to study Christianity and all "Western learning," crossed the border to work with him. By 1882, Korean Christians working under the Presbyterian ministers Rev. A.J. Ross and Rev. R.J. MacIntyre, were secretly sending home Korean translations of the New Testament.

Reverend Steven Colwell, then head of the Presbyterian Church U.S.A., was, at that time, a leading member of the Lincoln faction in America, in the Philadelphia circles of Friedrich List and Henry Carey. Carey's circle challenged the British Empire, and proposed to bring American freedom, science, and technology to China, Japan, and the rest of Asia.5

The missionaries' main method of education was the teaching of simple Christian hymns, in the chorale style of Johann Sebastian Bach. Soon, clandestine churches, organized around hymn singing, sprang up inside Korea, posting guards at the doors to warn against police arrest, while they quietly sang hymns inside. When, in 1885, the Korean Emperor finally gave missionaries permission to enter the country, Dr. Lee relates, "they found a warm welcome by about one hundred native Christian volunteers. With joy the missionaries cried out: "We were to sow the seed, but here we are now, already reaping!"

Early American missionaries working with Colwell's faction in Korea included the Presbyterian Revs. Horace N. Allen (1858-1922) and Horace G. Underwood (1859-1916), and the Methodists Rev. Henry G. Appenzeller (1858-1902) and Rev. William B. Scranton (1856-1922). The first U.S. adviser to Korea, Owen N. Denny (1838-1912), was also in the Lincoln faction; he was appointed U.S. consul at Tientsin, China by President Grant in 1876. Arriving in Korea in 1886, he strongly promoted her industrial development and independence.

As Dr. Lee also notes, Christianity and Western music were never seen as a foreign imposition in Korea, or as a "Western culture," but rather as an exciting discovery of a universal principle. Korean intellectuals sought out Christianity as a path to the dignity of the individual, for a population of whom more than ninety percent were illiterate peasants enduring virtual feudal serfdom.

"National self-determination and human emancipation comes from such a faith, that 'God is with us because of Christ,' " Dr. Lee writes, "as well as the self-conviction of men's equality, in the faith that 'God and man are equal within Christ only'... . Christianity, which claimed an equality of men under God, showed a new ideal to Koreans." He adds that for Korea, the impact of Western culture was neither to erase Korean culture, nor to merely transplant Christian culture, but rather to form a new, "third cultural formation, based upon our subjectivity ... the task of the Korean intelligentsia, which has the independent human will to create our history."

Before the missionaries came, most songs were the sole property of the aristocrats, "and by no means belonged to the people." The beauty of church hymns offered another power to the individual, the power of song, which Koreans eagerly made their own. They considered the singing of the hymns in the Korean language to be part of their own creation of a national culture. As Dr. Lee reports: "This writer was seven years old (in 1918) when he first heard the hymns, and was enchanted. Perhaps such was one reason this writer became forever fond of music. Although the story seems trifling, it explains ... Korea's profound relationship with the new culture. The holy hymn ... was not totally created by our composers, yet it can be said to be a kind of post-creation by its Korean recipients. It is a reflection of the very formation of Korean national life. ... It opened an avenue toward God, by pervading the entire population with songs, which once were the monopoly of special castes and shaman priests."

This same experience is described by African-American composers such as Roland Hayes. To overcome injustice, they wrote Spirituals about Christ as a living force for personal creativity, and thus for individual freedom. "My people found in the grandeur of the Biblical word and poetry," Hayes wrote, "a fountain of illimitable solace. From out the horizon of their tragic lot, rose a sublime illumination; an all-stimulating ray of hope for deliverance, through the Star of Bethlehem."6

Creating a National Language

Indeed, the written Korean langugage itself—and, in that sense, the nation—was created by the universal principles of Christianity and bel canto. In 1446, the Renaissance King Sejong had invented a true Korean alphabet, and a printing press well before Gutenberg, but the Korean "yangban" (landed oligarchy) defeated his plans to bring literacy to the population. Until the 1880's, Korea was still run by this feudal elite, which considered Korea almost a province of China. They wrote entirely in Chinese, including all poetry and music, while ninety-five percent of the population, which spoke Korean, was illiterate.

The Seoul court paid vassal allegiance to Beijing, and the Chinese army was stationed in Korea until 1895, which meant Korea was hardly a nation. Despite the 1847 opening of Japan, Korea was closed to foreigners until 1882, when the U.S., Japan, and Britain demanded port treaties.

"Christianity," however, Dr. Lee reports, "stood in the forefront of the campaign against illiteracy. It elevated the Korean alphabet, previously used only by lower classes and women, to a sublime level, to praise God." During the 1882-87 period, the Bible became the first piece of literature available entirely in Korean, and the hymns became the first songs in Korean. By the 1890's, the distribution of more than 700 million Bibles and four-part hymnals in Korean, engendered the first literature in the Korean language. This included the first newspaper in Korean, Independence News (1896), published by the young patriot Syngman Rhee; the first Korean grammar (1898); and the first Korean literary magazines and poems (1908).

The missionaries founded the first universities in Korea, teaching in Korean for the first time, including Yeonhi College (now Yonsei University), Baejae School, and Ewha Women's University.

By the 1890's, the Japanese army was vying with the Chinese army for control over Korea, and the Christian hymns became the organizing principle of a new nationalist revolt. "The nation was full of the sound of the holy hymms and church bells, which resounded through the streets and alleys," Dr. Lee reports. Korean Christians and American missionaries led singing street demonstrations which became "the manifestation of the national distress" against foreign occupation, and a call for the formation of an independent Korean nation.

'Project Brahms' and National Music

A key representative of the international "Project Brahms" to Korea and Japan was Franz Eckert (1852-1916), from the Dresden School of Music, who was conductor of the German Navy Band, and principal conductor of the Kaiser's Prussian Royal Orchestra. Through officials of the Navy in Hanover and Berlin, it is possible that Eckert knew Johannes Brahms personally.

In 1879, the American voice teacher Luthor W. Mason (1828-96) came to Tokyo, to found Japan's school music program, based on teaching children to sing bel canto; school music in Japan is thus called "Mason Song." Mason had previously taught bel canto music education in Germany, publishing Die Neue Gesang-schule (The National Music Course).

That same year, 1879, Franz Eckert was brought by the German Navy to Tokyo, to teach Western musical instruments to the Japanese. He worked closely with Mason. Eckert founded the Japan Music Center, today the prestigious Tokyo College of Western Music, and was Court Music teacher to the Royal Household, where he assisted the composition of Japan's national anthem, "Kimi ga yo," a hymn to Emperor Meiji. Japan's feudal warlords were then trying to crush the newborn central government, and the anthem rallied the Japanese population in support of the Meiji Restoration movement to create a modern industrial nation.

In February, 1901, Eckert moved to Seoul to found the Korean Army Band, later the "Emperor's Orchestra," the first Classical music school in Korea. He mobilized a cadre of students in Seoul to the feat of mastering all the Western musical instruments within months, so that by September of that year, a twenty-seven-piece band was able to play for the Korean Emperor's birthday before the assembled foreign dignitaries, drawing international notice.

Another participant in 'Project Brahms" was Eli Mowry (1877-1969), an American Presbyterian missionary, who arrived in Pyongyang in 1909, and with his wife formed the first choirs and keyboard schools in Korea, and the first orchestra in Pyongyang, at Pyongyang Union College. He especially concentrated on youth from the poorer classes. "He would personally take trips around the villages, and pick up able youths to afford them the new education," Dr. Lee reports. "He taught them the new science and the music, including organ ... [and] including piano lessons under Mrs. Mowry. Thus he instructed the holy hymns, and introduced Western music to the farmer, carrying along his portable organ, in four octaves; the four-part chorus began to appear, one by one, even in the country churches. ... Many men became Christian under the influence of such hymnal choruses. Many musicians also came from such missionizing... . Music to him was the very religious act itself."

Eckert's work in particular had the "fingerprint" of Project Brahms, described by Brahms' biographer Gustav Jenner, and by Dvorak: the comprehensive study of folk music in the native language, which is then elevated to art by Classical principles. "Eckert is known to have much interest in our traditional music, and studied often Korean songs and folk-lore. He composed numerous pieces on the pattern of such themes," Dr. Lee reports.

Brahms and Dvorak made a study of the principles of national music. They argued in the tradition of Abraham Lincoln, against the British idea of empire, in which one nation holds others as slave states. Instead, they wrote, people bound together by a national language, history, and culture, require politicial sovereignty and freedom. This means every nation must have music in its national language. As great as was the Classical tradition in Italian, from the Renaissance to Mozart, and while everyone should learn to sing in Italian, people of all nations must not sing only Italian.

Brahms made his exhaustive study of the German volkslieder, and Dvorak his studies of Czech folk songs, and African-American Spirituals in English, to show how each song was based on the inherent musical principles of each language.

For example, as Leonardo da Vinci first documented in his drawings, the quality of the vowels of human speech are associated with different pitches. These inherent vowel pitches come from the shape in which we hold the vocal tract when speaking. An /i/ (as in "Aida") is created by the smallest mouth position; it is the highest pitched vowel. The /a/ (as in "Aida") is made by opening the mouth more; /o/ is lower, and /u/ (as in "too") is made by opening even more, and extending the lips; it is the lowest vowel. One can feel the space inside the mouth go from smaller, to larger, by saying: "ee, ah, oh, oo"

So, in a sense, each language has its own musical score. A famous example is Schubert's "Ave Maria." The musical melody rises as the vowels of Latin rise, from the lower /a/ to the higher vowel /i/, and falls, as the vowels fall back to /a/: "A-ve Ma-ri-a." In German, Brahms set the musical theme of his volkslied "Sonntag" to rise, where the vowel sounds of the folk text rise, from /o/ to /a/ to /i/, on the words "So war ich doch die; and then the melody falls, where the vowels fall back to /o/ at "ganze Woche" [see: Figure 12].7

It is clear from the results that Franz Eckert studied Korean (and Japanese) folk songs, in this manner, teaching these methods to his students. It was as part of this project that Eckert helped to compose the national anthem of Korea, as well as that of Japan.8

It was a great advantage that King Sejong's Korean alphabet itself comes from a Renaissance study of this same inherent pitch of the vowels of speech created by the human vocal tract. It is based on a grid of the seven Korean vowels, which are close to the seven basic Italian vowels. The shapes of Sejong's letters are not based on Chinese characters, but rather are noted by philologists for being based on schematic drawings of the physical shape of the mouth when each of the vowels is spoken.

Every letter ends in a vowel sound, and no consonants stand alone, yielding a vowel-based pattern similiar to Italian. The Korean Lyric Songs make use of these "vowel melodies" in Classical style. For example, compare to "Ave Maria" and "Sonntag," the passage in "Azaleas": "Yongbyon ui yak san chindalrae-ggot (At Yongbyon the mountain-blooming azaleas)" [see: Figure 13]. The melody begins in the first register on the repeated lower /o/ sound of the town, Yongbyon; then rises into the second register on the higher vowel sounds of /i/ and /a/ in "ui yak san chin"; and then falls back to the first register on the /o/ of "ggot" (flower).

The characteristic rhythms of the Korean Lyric Songs, such as 6/8, also clearly derive from the polysyllabic nature of the Korean language. Korean, which has neither articles nor prepositions, but has frequent post-positions, is often in trochaic (/-) or the related triple dactylic meter (/- -). These are quite different from the typical English iambic (-/ -/), as in: "It came upon a midnight clear"), which has a tendency to 4/4 or 2/4 time.

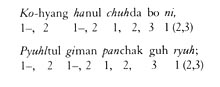

"Thoughts of My Homeland (Kohyang Saeng-gak)," a quite Schubertian piece by Dr. Hyun Jae-myung (Rody Hyun) (1902-1960), shows the typical Korean trochaic rhythm and its tendency to fall into a dactylic triple meter. In the poem, also by Dr. Hyun, the key second verse, which speaks of his homeland (kohyang) begins in trochaic and winds up in dactylic:

|

|

This results in a musical setting in a lilting 6/8 [see: Figure 13, verse 2].

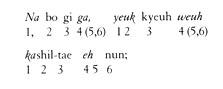

The opening line of the original poem "Azaleas" by Kim So-weol, begins outright in a triple dactylic rhythm:

|

|

When Kim Dong-jin composed the music to set this poem, he used a duple time signature, 4/4, but the internal rhythm of the accompaniment and the melody is the triple meter 12/8 [see: Figure 14]. Kim Dong-jin (born 1913), after his first song collection Kagopa (Wishing to Return), (1933), published many Lyric Songs, extensive instrumental music for strings and orchestra, and two operas. He was a minister's son, and began his early music studies with the missionaries. In February, 1995, Kim traveled to Los Angeles, to conduct the chorale version of his song "Kagopa," with combined children's choirs from Seoul and Los Angeles, and Korean-American soloists.

Early Korean Songs

So "Korean" were Christianity and the hymns, that they became the basis for the Korean national movement.

The early Korean Western songs, called "Chang-ga" ("singing songs"), based on the hymns, were nationalist tunes. "The Chang-ka in Korea derived from the holy hymn," Dr. Lee wrote, "was a religious expression for Korean nationalism, springing from the tragic fate of fallen Korea ... an intensive pulse, the national call for independence."

The students of the American missionaries included all the early Classical musicians in Korea. Kim In-sik (1885-1963), the first Classical Korean composer, relates that in the 1890's, "anyone who wished to learn music, had to learn it at church. ... I used to appreciate with deep interest the organ's tone and the hymn chorus." At eleven, he entered the Christian Sungdeok School. At sixteen, Kim approached two local missionary wives in Pyongyang for voice lessons. "Since I had little sheet music, I would transcribe the musical notes at their houses," he wrote. "Finally I copied every piece of music paper they had."

Kim Yeong-Hwan (1893-1978), Korea's first concert pianist and an early song composer, was the son of a leader in the Christian and Western education movement. At age six in Pyongyang, Kim fell in love with the organ and would beg to go to the missionaries' homes to hear it. Kim's father, who studied with Kim In-sik in Seoul, later brought home an organ, 120 miles by mule to Pyongyang. "I felt as though I could fly into the sky," Kim wrote. "Every day on my return from school, I would throw my school bag away, and rush to the organ to play. The sound was so magical." When his grandfather refused to let him become a musician, Kim ran away to Tokyo, to study with the German professors at Ueno Music College.

Classical Transformation

Brahms had stressed, however, that in Classical music, a poem or folksong in the national language cannot simply be "copied" in the musical setting. Rather, the Classical composer must now create something new, using Classical bel canto and contrapuntal principles.

According to his student Gustav Jenner, Brahms taught that first, the folk poem or song must be studied, completely memorized, and taken inside the composer's soul. "Brahms' first requirement was that the composer know his text in detail," Jenner wrote. "By this he also meant that he should be completely clear about the poem's structure and meter. Then he would recommend that before composing to a poem, I should carry it around in my head for a long time and should frequently recite it to myself aloud, paying careful attention to everything pertaining to declamation, and especially noting the caesuras. ... Those places where punctuation is used in speech are set in music as cadences; and just as the poet puts together his sentences through sensible construction, using commas, semicolons, periods, etc., as signs, so likewise does the musician have available to him full and half cadences in manifold forms... ."

Next, however, Brahms taught, this material is to be transformed by the composer. The particulars—this word, that sound—are now put aside, in favor of penetrating deeply into the pre-conscious idea of the poem, the "unheard sounds" which Keats said "are sweeter still"—that is, the metaphor of the poem.

"Brahms never composed so-called 'mood-poems,' which consist of an assemblage of word-paintings," Jenner noted. "Whenever the melody followed too closely the word expression, he would reproach this, saying: 'More from the whole!'—thus getting right to the heart of the matter... . He therefore advised me, if at all possible, not to proceed to the working-out of a song, until its full plan was already in my head, or on paper. 'Whenever ideas come to you, go take a walk; then you'll find that what you had thought was a finished idea, was only the beginnings of one... ,' Brahms said." In a good song, Brahms taught, "[t]here is an underlying mood which is maintained through all particulars or all the varied images."9

After 1900, when skilled musicians such as Franz Eckert and Eli Mowry arrived, they taught this principle. Soon Korean songs began to take a new direction.

Kim In-sik's "Old Laundress," composed in 1905, was the "first modern compostion in Korea," Dr. Lee writes, because it has become metaphorical. The poem opens:

By the crystal brook in the valley

An old woman does her laundry

Over the western mountain, the sun falls.

The poem and song are not explicit, but rather by "expressing individual sentiment," he notes, they convey a "conscious literary intent" in the style of the songs of Schubert and other European lieder. The image of the nation, over whose weary head the sun is setting, is poetically clear. "Here we see from Chang-ga, the sprouting of the Art song," Dr. Lee notes.

It is no accident, that in 1905, the Japanese forced Korea into a Protectorate Treaty, and in effect seized the government in Seoul openly for the first time. The development of metaphor had become a terrible necessity.

Ironically, the early Korean freedom fighters were backed by Japan—because until 1890, Japan was the main ally in Asia of the Abraham Lincoln faction in America. Koreans went to Japan to study Western science when Korea had no universities. In 1884, Japan backed a revolt of Korean patriots against the feudal Seoul court, demanding that American technology and Christianity be allowed into Korea. Koreans went to Japan to see the first railroads, and one of the first Chang-ga songs in Korean was "The Railroad Song," modeled after a similar song written in Japan, to celebrate the first railroad there.

After 1900, however, the British Empire accomplished a series of coups inside the U.S., Japan, and other countries, restoring their fellow imperialists to power. The British-authored 1901 assassination of President William McKinley brought the imperialist Teddy Roosevelt to power. Britain's 1902 Anglo-Japan Treaty, and the 1905 Russo-Japanese War (into which Tokyo was pushed by Britain), brought the imperialists to power in Japan. After making her a Protectorate in 1905, Japan formally annexed Korea in 1910.10

Metaphor Creates a Nation

The Japanese Occupation looted Korea economically and culturally. The currency and official language were changed to Japanese. Transport, communications, and some eighty percent of Korean rice lands were expropriated, forcing millions of peasants as refugees into Manchuria and Siberia.

During the Occupation, "we were almost forbidden to speak our own language," Madame Kim Cha-Kyung, one of Korea's first opera singers, told me, "but we could sing. It was during these times, the period after 1910, especially from the 1920's, that the true art songs known as Korean Lyric Songs began to be composed."

Art songs did not spring up automatically. The early composer Yi Sang-jun (1884-1948), for example, in his 1918 Chang-ga Collection, published a song called "Separation." This, Dr. Lee notes, is "but a camouflage of the 'Exile Song'," composed after the 1911 "105 Persons Incident," by An Chang-ho, when the Japanese exiled many leading intellectuals to Manchuria and Siberia. "Separation" had the same tune, with the word for "homeland" in "Do not grieve at my leaving, homeland" replaced by the word "friend." "This means Japanese surveillance was becoming more harsh," Dr. Lee points out.

A major change took place, however, after the March First Independence Movement of 1919, in which Korean patriots, including some of the leading poets, read a Korean "Declaration of Independence" in Seoul, sparking a national uprising. The Japanese slaughtered 6,000 people in cold blood in a peaceful crowd of demonstrators, arrested 50,000, and crippled the national leadership. Dr. Syngman Rhee was forced to form a government-in-exile in Shanghai.

The Japanese Occupation then announced a cultural "final solution." Korean-language newspapers and printing of any kind were banned. Korean was banned both in schools and in private homes, and professors of Korean were arrested as criminals. All Koreans were forced to take a Japanese name. Koreans responded to this tragedy by resolving for a long war.

Korean artists realized they would have to mobilize the full power of metaphor in the high Classical style, in order to give the population the internal strength to survive such a period. Although many went to the U.S. and Europe for study, most returned home, in order to give moral encouragement to their people. Working as they were under the Japanese-run state musical system, they had to function at a very high level.

"The composers put into music, what we could not say in words," composer Kwon Gil-sang told me in a recent interview. "It was always very poetic. It could never be specific; to speak openly of the nation was not allowed. Sometimes they seem to be only simple love songs, a boy's love for his sweetheart. But the people knew what the poems meant."

"That 'tears' and 'lover' appearing in a song, do not necessarily mean 'lover' per se, is verified by the fact that ancient Korean poems used the 'beloved' as the symbol for the nation," Lee You-sun reports. "The early Christians used to symbolize their religion with the shape of the fish, under persecution by the Roman imperialists. Likewise, Korean intellectuals would develop their national liberation movement through a new literary and song movement."

The only ironic benefit, was that German Classical music was very popular in Japan. Under the Japanese, many Korean musicians were able to study with German professors in Tokyo. Songs of Schubert such as "Heidenröslein" were sung in Japanese grade school, so they were taught to Korean school children as well. This was because Western musicians and missionaries created the school music program in Japan; Japanese students, for example, sing "Auld Lang Syne" when they graduate from high school.

The first true art songs were composed by Hong Yeong-hu (1897-1941), who was called "the Korean Schubert." After studying violin with Kim In-sik, he was sent to Japan, under the Japanese name Hong Nan-pa, to study at Ueno Music College. In 1920, the year after the massacre, he composed "Balsam (Bong Seong Hwa)." Dr. Lee calls it the first Korean Lyric Song, "making a metaphor of the tender balsam plants, for the Koreans who were trampled under the boots and bayonets of the Japanese Imperial Army."

The poem is refined artistically, Dr. Lee notes, developed in metaphor, instead of in simile, and the melody and accompaniment attain a high artistic level not found in conventional hymns and Chang-ga songs. On returning to Korea, Hong continued as a violinist and published collections of songs. In 1931-32, he also studied at the Sherwood Music School in Chicago, and on his return, he organized the first orchestra of Korean state radio (then NHK, the Japan Broadcasting System).

Hyun Jae-myung (1902-1960), a student of Eli Mowry, composed "Thoughts of My Homeland (Kohyang Saeng-gak)" [Figure 14] in 1928, while studying in the U.S., at the University of Chicago, and the Gunn School of Music. Dr. Hyun published dozens of songs, and was head of Seoul National University Music School, teaching the next generation of composers, including Kwon Gil-sang. In 1933, on the publication of his Song Collection No. 2, Dr. Hyun, an accomplished tenor, gave a recital to present the songs, with our historian Dr. Lee You-sun, another accomplished tenor.

It was also during the 1920's that children's songs became a movement in Korea, starting with the publication of the song collection "Sopa (Gift of Love)" in 1922 by Bang Jeong-hwan, who founded the Children's Society for composers of children's songs. Teaching children songs in Korean, using traditional Italian bel canto, became one of the only means left to preserve the national language.

It was also an effective means of nationalist agitation against the Japanese, because children go everywhere. "Like smoke, the songs spread out to schools and alleys," as Dr. Lee puts it, "and soon were sung nationwide." The Japanese were forced to issue edicts prohibiting children from singing, which were of little use, and made them look ridiculous. Many of the next generation of Korean composers such as Kwon Gil-sang were some of those children, who learned to sing so patriotically during the Occupation.

Meanwhile the instrumentalist students of Franz Eckert and the Emperor's Orchestra became the new generation of school music teachers. In 1916, Franz Eckert died in Korea, and the band struggled on as the Seoul Band, because the population took such solace from its concerts. After the 1919 Independence Movement slaughter, the Band gave a memorial concert at the Seoul YMCA Hall, and began to suffer heavy harassment from the Japanese.

"Thus the band members dispersed one after another, embracing their beloved instruments," Dr. Lee reports. "They could not betray the cause of Herr Eckert, who had always been their source of courage in such adversities, who had dedicated himself to Korean music until he was buried in this land. Members transferred to schools to teach music, and to organize and create school bands. Eventually the seed Eckert sowed, turned out greater fruits in the schools."

Division and Heroism

Korea survived the Occupation, only to be divided after 1945, and her tragedy continues today. Millions of families are still divided by the De-Militarized Zone between North and South Korea. Many nations are confronted by tragedy, but after the war, Korean composers did something which is not usual. They responded with heroism, for they continued to compose Classical songs, as a creative way to overcome tragedy.

"After the war, in 1945, conditions in Seoul were bad. Food and fuel and clothing were scarce," composer Kwon Gil-sang said in an interview, explaining how he came to be a founder of several children's choirs in Seoul. "We had to find some way to uplift the children." And then came the Korean War, and more devastation. [see: Interview, this issue]

Kwon Gil-sang wrote his famous song "At the Flower Garden (Kkot bat tai seo)," in 1953, at the end of the Korean War. In the poem, the poet remembers planting a garden with his father as a child. "When I think of Papa, I see the flower vines growing up, winding together," he says, "Papa taught me, that we will always be together, if I live like the flowers, beautiful and strong." The image of the Fatherland, and the idea that it can be united by moral living, and by creating Beauty, is powerful. At Korean concerts, the song is sung by the whole audience, just as African-Americans sing "Lift Every Voice," known as the "Negro national anthem." Kwon's own father was a Presbyterian minister.

The Sublime and Art

These songs should be an inspiration for all the people of the world who, as Goethe says in the Beethoven song setting,"know longing." Korea is a country first trampled, then physically cut in two—but the hearts of her artists are great enough, that with music, the soul rises high enough, to foresee a better day.

Many nations face tragedy, but have not achieved such a response—and they have been destroyed. This makes clear that romantic fools are wrong to glorify tragedy per se as heroic. Nor does art spring from tragedy.

Like the African-American Spiritual, the Korean Lyric Song demonstrates that art often does, however, spring from an heroic response to tragedy, from a creative act, which forges a new way through which "we shall overcome."

Dr. Lee differentiates the creative optimism of the true Lyric Songs as art, from the merely popular songs written to bemoan Korea's oppression by the Japanese. These songs were pessimistic, impotent. He cites "Song of Hope," which appeared in 1923. The words condemned Korean collaborators of the Japanese to the void. "What a sad nihilism," Dr. Lee chides. "We should, rather, say it is the 'Song of Despair.' " He relates how a famous Korean soprano threw herself off a ship and drowned, singing this song, on her passage home—after making recordings in Tokyo for the Japanese. Her nihilism did not even stop her from being a collaborator. "With the appearance of 'Balsam,' and the 'Song of Hope,' " Dr. Lee writes, "the Art song, and the popular song, are completely differentiated."

Mankind can read the freedom of its soul in the stars, as the poet Friedrich Schiller writes in Wilhelm Tell. But what is it in the stars, but the Divine harmony itself, which man sees? So, it is only God's divine spark in man, which gives man absolute freedom.

Yet, man is mortal, and cannot be fully one with God on Earth. In this awesome paradox lies the sublime, that mixture of joy and tragic longing of which Schiller wrote, which can only be expressed in metaphor. Beethoven, in "An die ferne Geliebte (To the Distant Beloved)," speaks not merely of the singer's sweetheart, but ultimately of God, referred to in some German classics as "der Ferne," the Distant One.

Yet it is the metaphorical demonstration of this beautiful paradox which sets us free, in fact, to do all that we might do, on Earth. Beethoven, in his cycle, does not despair, but resolves to create songs—and to teach them to his posterity. So, Schiller says, man must create art—to demonstrate efficiently the immortality of the soul, since the genius of a great composer lives on for generations.

Thus, man approaches nearer to God, and in this we see the universal nature of man.

Notes1. You-sun Lee, Phd., A Hundred Year History of Western Music in Korea (1885-1985) (Seoul: Eumak Choon-choo Publishing Co., 1985), in Korean; The History of Western Music in Korea, unpublished English manuscript, 1988.

2. Dennis Speed, "African-American Spirituals and the Classical Setting of Strophic Poetry," Fidelio, Vol. III, No. 4, Winter 1994.

3. A Manual on Tuning and Registration. Vol. I: The Human Singing Voice, ed. by John Sigerson and Kathy Wolfe (Washington, D.C.: Schiller Institute, 1992), Introduction and chap. 2; see also, Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., "Mozart's 1782-85 Revolution in Music," Fidelio, Vol.1, No. 4, Winter 1992.

4. Gustav Jenner, Johannes Brahms as a Man, Teacher, and Artist (Marburg: Verlag N.G. Elwert, 1930), pp. 33-4.

5. Anton Chaitkin, "America and Russia: How Nationalists Created the Modern World Economy," Executive Intelligence Review, Vol. 22, No. 35, Sept. 1, 1995, pp. 42-44; also, "Leibniz, Gauss Shaped America's Science Successes," Executive Intelligence Review, Vol. 23, No. 7, Feb. 9. 1996, pps. 22-23, 25-57.

6. Roland Hayes, My Songs (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1948).

7. A Manual on Tuning and Registration, ibid., pp. 157-171.

8. Amalie Eckert Martel, Franz Eckert, Mein Vater der Componist der Japanischen National-hymn "Kimi ga yo," cited in Lee, p. 81.

9. Gustav Jenner, ibid., pps. 35-6, 42-3.

10. For an historical overview of the role of the British Empire in Asia, see EIR Special Report, "Britain's Pacific Warfare Against the United States," Executive Intelligence Review, Vol. 22, No. 20, May 12, 1995, pp. 12-69.

Color Chart of the Registers of the Six Species of the Human Singing Voice

National Conservatory of Music Movement ( And Why You Should Join)-

How "Country Music" Was Designed to Make You Stupid

Save the African American Spiritual! (Dialogue with William Warfield

and Sylvia Olden Lee)

Mozart's Ave Verum Corpus and the "Test of Death"

with Score for Voice and Strings

LaRouche Articles on Mozart's Revolution, and Metaphor and Politics as Art

Other Fidelio Articles on Music, Tuning and Tuning History

The Poetic Principle- a Discussion on the Unity of Science and Art

schiller@schillerinstitute.org

The Schiller Institute

PO BOX 20244

Washington, DC 20041-0244

703-297-8368

Thank you for supporting the Schiller Institute. Your membership and contributions enable us to publish FIDELIO Magazine, and to sponsor concerts, conferences, and other activities which represent critical interventions into the policy making and cultural life of the nation and the world.

Contributions and memberships are not tax-deductible.

VISIT THESE OTHER PAGES:

Home | Search | About | Fidelio | Economy | Strategy | Justice | Conferences | Join

Highlights | Calendar | Music | Books | Concerts | Links | Education | Health

What's New | LaRouche | Spanish Pages | Poetry | Maps

Dialogue of Cultures

© Copyright Schiller Institute, Inc. 2001. All Rights Reserved.