This Week in History

July 13-19, 2015

Rembrandt van Rijn

‘Love Gives Birth to Art’

July 15, 1606

By Bonnie James

Click on any image to view full size

The life of Rembrandt, born July 15, 1606, was, to a significant degree, affected by two history-changing events. The first took place on Dec. 20, the year of his birth: Two English merchant companies, under the patronage of King James I, set sail from London, their destination, the New World, where, on May 14 of the following year, 108 settlers of the Virginia Company landed at Jamestown Island, to establish the first English colony in the Americas.

Four decades later, in 1648, the Treaty of Westphalia ended the horrific Thirty Years War, which had devastated large portions of the population and territory of Europe.

Rembrandt, through his prolific artistic output, profoundly and unforgettably, gave expression to these momentous changes, which forever altered the course of human history.

Figure 1

A self-portrait from 1659, soon after Rembrandt emerged from bankruptcy. It is on permanent exhibit at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. |

The triumphs and vicissitudes of his life, about which he never wrote, can be read, nonetheless, in his many self-portraits (Figure 1), which spanned four decades. His hundreds of genre paintings, drawings, and prints, which today grace numerous of museums around the world, continue to bring his art to millions.

Rembrandt's Leiden

Rembrandt was the ninth of ten children, born to a prosperous miller of Leiden, Harmen Gerritsz. van Rijn, and his wife Neeltje van Suijttbroeck, the daughter of a baker. The place of his birth was an auspicious one. Early 17th-Century Leiden, in the northern Netherlands, with its famous university, was an intellectual and artistic center of Europe, in which a significant degree of religious toleration prevailed. Thus it became a magnet to those fleeing religious persecution. The immigrants included Puritans from England; Jews from Spain and Portugal, and from Eastern Europe; as well as Catholics and Protestants of all denominations. The influx of migrants added to the cultural and economic vitality of the city, and helped to shape Rembrandt's earliest impressions.

In 1618, the year of the outbreak of the Thirty Years War, Maurits, Prince of Orange, overthrew by force the ecumenical government of Leiden, and installed a Calvinist (Dutch Reform) dictatorship. The political opponents of the House of Orange and its Calvinist allies in Leiden were loosely organized around the followers of the Remonstrant faith, another branch of the Protestant Church, with which Rembrandt and his family were associated. When the “Orange Revolution” in Leiden overturned the more moderate Protestant leadership, outcast groups, including both renegade Protestant sects and Catholics, tended to coalesce around the Remonstrants. It was the members of this latter “coalition,” with its ties to Amsterdam, who would constitute the humanist circles that nurtured Rembrandt in his early years in that city.

As the son of a relatively prosperous tradesman, Rembrandt was able to attend the Latin School in Leiden, from age 9 to 13. In 1620, he was registered at the University of Leiden to study literature. Beginning at age 15, he was apprenticed to a local artist, Jacob Isaacsz. van Swanenburg, with whom he studied for about one year. His exceptional gifts as an artist soon won him the patronage of some of the leading figures in Leiden, who sent him to Amsterdam for further training as a painter in the studio of Pieter Lastman. Before long, Rembrandt would become the leading portrait painter in a city that was, like Leiden, a refuge for those seeking religious toleration; Rembrandt lived in the Jewish quarter of the city, and many of its inhabitants became the artist's models for his Old and New Testament figures.

Amsterdam was, at the same time, the headquarters of the imperial Dutch East India Company (founded 1601-02), a tight-knit cabal of oligarchical families. In 1606, the year of Rembrandt's birth, the first Dutch slave ships sailed with their human cargo to the New World.

The Painter

Figure 2

Rembrandt depicted his wife Saskia as the Goddess Flora, in 1634, the year of their marriage. It is now in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. |

Once established in Amsterdam, Rembrandt, not only found success as an artist, his marriage to Saskia van Uylenburgh (Figure 2), the daughter of a prominent figure, not only brought him additional commissions, but great happiness as well, as can be seen in his beautiful portrait of Saskia. One art historian has suggested that a self-portrait of Rembrandt with Saskia be seen as an illustration of the Dutch maxim, Liefde baart kunst (Love gives birth to art).

In addition to his many genre paintings, portraits, and self-portraits, Rembrandt became the greatest printmaker of his time. With his etchings and engravings, each of which produced hundreds of copies, he was able to reach a much wider audience, thus spreading the ideas of the Renaissance to a popular audience. In a number of etchings and paintings from this period, Rembrandt gives visual form to the idea of compassion, or agapē, expressed in the Treaty of Westphalia. The most famous of these is his etching, “Christ Healing the Sick” (Figure 3), from 1648, the year of the Treaty; it beautifully captures its meaning: that to secure the peace, “each Party shall endeavor to procure the Benefit, Honor and Advantage of the other.”

Also known as “The Hundred Guilder Print” because of the exceptionally high price paid for it, the image represents the passage from the Gospel of Matthew: “And great multitudes followed him; and he healed them there.”

Figure 3

"Christ Healing the Sick" ("The Hundred Guilder Print"), an etching from 1648, the year of the Peace of Westphalia, based on the Gospel of Matthew. |

The work, done in etching, drypoint, and engraving, took several years to complete. Rembrandt places Christ at the center of the composition, where He is illuminated by a strong light from the left, but He also emanates a powerful light from within: By this light we can clearly “read” the expressions and thoughts on the faces of those around him. From the right, a crowd enters through the city gate: They are the sick, the crippled, the aged, who beseech His help. Two mothers approach Christ, offering their children for His blessing; Peter, at Christ's right hand, tries to hold the women back, but Christ reproaches him: “Suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me: for of such is the kingdom of heaven.”

There is also the young man, who came to Jesus seeking eternal life. Jesus tell him: “If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come and follow me.” But when he heard this, "he went away sorrowful: for he had great possessions.'' Jesus tells his disciples, “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of Heaven.” Rembrandt (somewhat fancifully) depicts, on the far right of the composition, a camel coming through the gate!

In this powerful image, Rembrandt sums up the meaning of the Treaty of Westphalia.

Bankruptcy

In 1656, Dutch East India Company shares plummeted on the Amsterdam Exchange and many investors were ruined. Among them was Rembrandt van Rijn, now 50, who was declared bankrupt and whose possessions were put up for sale. The process leading to Rembrandt's bankruptcy however, was not so simple; his finances unraveled over the decade of the 1650s, as powerful patrons abandoned him, and the vultures closed in. In January 1653, with the country at war with England, and finances tight, Rembrandt's creditors called in their loans. The details of all this are somewhat murky, although certain facts are known. In order to hold off his creditors, he borrowed additional funds, while a large portion of his debt was sold off to that day's version of hedge fund traders. Things continued to fall apart; two sales of his household goods took place by the late Summer of 1655. Finally, in November of 1657, Rembrandt was forced to sell off his house, and his entire art collection, a collection he had spent a lifetime gathering--dozens of Dürer and Mantegna prints; copies and engravings after the greatest works of art in Italy--those of Leonardo, Raphael, and others, as well as a quarter-century's production of his etched copper plates.

There was a decidedly political motivation behind the financial persecution of Rembrandt: the key moneylender who finally called in the chips, was Gerbrand Ornia, one of the richest men in Amsterdam. Ultimately, it was Ornia and his ally Cornelius Witsen, a corrupt city official, who forced Rembrandt to sell his house for a pittance, leaving him nearly destitute.

The Phoenix

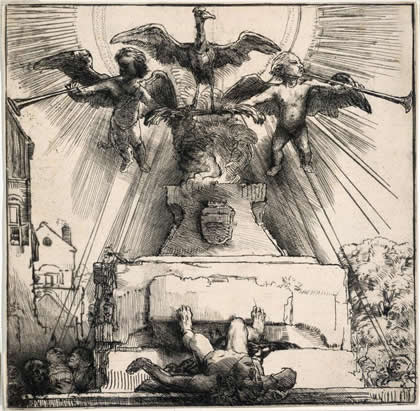

Figure 4

"An Allegory: The Phoenix," an etching from1658, following a long period of personal and financial tragedy for Rembrandt. |

By 1658, Rembrandt had begun to emerge from bankruptcy and to put his affairs in order. He had lost his home and his great art collection; his common-law wife Hendrickje had been expelled from the Dutch Reformed Church for living in sin with the artist. His former patrons and friends had abandoned him. But Rembrandt was not defeated. That year he produced one of his most personal and innovative prints, “An Allegory: The Phoenix” (Figure 4). In this etching, Rembrandt takes the mythical story of the fabled bird that consumes itself, and then rises from its own ashes, restored to life.

The “Phoenix” can be read as Rembrandt's metaphor for his own “resurrection” from the humiliation and defeats he had suffered.

In Rembrandt's image, the Phoenix stands atop a huge pedestal, as two putti blare forth the news on their trumpets that he has risen; a huge Sun, whose rays penetrate the composition, rises behind him. A youth, whose dramatically foreshortened figure lies at the base of the pedestal, and whose head extends over the edge of the picture into our space, suggests nothing so much as a Classical Greek statue, now fallen.

Surely, this "ugly duckling" of a Phoenix is Rembrandt himself, risen from the ashes of his trials and tribulations, ready to take on the world again. He is conscious of his immortality; he knows that he, through the genius of his works, will long outlive his enemies.

Postscript

In the years following his financial recovery, until his death in 1669, Rembrandt continued to produce many of his most beloved works. These included a dozen self-portraits, among them, his "Self-Portrait as St. Paul" (1661), and the one pictured here in Figure 1; "The Syndics of the Cloth Guild" (1662), his scathing group portrait of the leading merchants and money-lenders of Amsterdam; and "The Jewish Bride" (1665); not mention numerous drawings and etchings.

Note: For a more thorough examination of Rembrandt's life and work, see Bonnie James, “Rembrandt's Thirty Years War vs. Anglo-Dutch Liberal Tyranny,” EIR, Jan. 26, 2007.